Cognitive Disconnect:

Understanding Facebook Connect Login Permissions

Nicky Robinson

Princeton University

Joseph Bonneau

Princeton University

ABSTRACT

We study Facebook Connect’s permissions system using

crawling, experimentation, and user surveys. We find several

areas in which it it works differently than many users and

developers expect. More permissions can be granted than

developers intend. In particular, permissions that allow a

site to post to the user’s profile are granted on an all-or-

nothing basis. While users generally understand what data

sites can read from their profile, they generally do not un-

derstand the full extent of what sites can post. In the case of

write permissions, we show that user expectations are influ-

enced by the identity of the requesting site although this has

no impact on what is actually enforced. We also find that

users generally do not understand the way Facebook Con-

nect permissions interact with Facebook’s privacy settings.

Our results suggest that users understand detailed, granular

messages better than those that are broad and vague.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

D.4.6 [Security and Protection]: Access Controls

General Terms

Security; Human Factors

Keywords

Online social networks; permissions; privacy; Facebook

1. INTRODUCTION

Single Sign-On (SSO) systems allow users to log in to

websites (called relying sites or relying parties) using their

username and password from a third-party identity provider.

This creates fewer passwords for users to remember, theo-

retically meaning that they can have more complicated and

therefore more secure passwords [22]. Facebook Connect

1

is

1

Facebook Connect is now technically called Facebook Login

but is still frequently referred to as Facebook Connect.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full cita-

tion on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than

ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or re-

publish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission

and/or a fee. Request permissions from [email protected].

COSN’14, October 1–2, 2014, Dublin, Ireland.

Copyright 2014 ACM 978-1-4503-3198-2/14/10 ...$15.00.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2660460.2660471.

perhaps the most popular SSO system on the web today. A

key reason is that Facebook Connect, like many SSO sys-

tems based off of the OAuth protocol, does more than just

allow a user to sign in: sites can request access to read parts

of the user’s Facebook profile or write data back their pro-

file. This has been sufficient in practice to overcome the lack

of adoption incentives for relying parties which has plagued

many other SSO systems on the web [25].

An important selling point is that Facebook Connect re-

quires relying sites to request a specific set of permissions

from the user up front in order to read or write data from

the user’s profile. These are presented to the user in a se-

ries of dialogues (shown in Figure 1) which the user must

approve prior to logging into a relying site for the first time.

In the words of Facebook, “The user will have total control

of the permissions granted” [19].

Effective user control relies both on Facebook granting

only the permissions intended by developers and on users

correctly understanding the permissions they approve. We

explore both assumptions and show that:

• Facebook Connect sometimes asks the user to autho-

rize more permissions than the developer intended to

request.

• Write permissions are granted to sites on an all-or-

nothing basis. For example, if a site wants the ability

to update the user’s status, it must also gain the ability

to upload photos.

• Users generally understand which read permissions are

being requested when they log in, although many do

not realize they are granting access to data they have

marked as private using their privacy settings.

• Users generally do not understand the variety of write

permissions sites will receive upon authorization. This

indicates that, despite Facebook’s claim that all-or-

nothing write permissions are “simpler” for users to

understand, users understand the more granular read

permissions better.

• Users are influenced by the identity of the relying site;

for example, they are much more likely to understand

a photo sharing website can upload photos to their

account. This suggests users are assuming a contextual

integrity model of privacy [20], although this is not

implemented technically.

Figure 1: Examples of messages presented to the user. From left: Read permissions message from Yahoo.com, write permissions

message from Pinterest.com, and extended permissions message from AddThis.com.

2. IMPLEMENTATION OF FACEBOOK

CONNECT PERMISSIONS

The first step in determining whether the permissions sys-

tem provides users with effective control is understanding

which permissions are actually granted when a given autho-

rization message is displayed. Facebook Connect’s process

of a site requesting permissions from a user can be broken

down into three steps:

1. During login flow, relying parties request a set of per-

missions from the Facebook Connect API. We’ll call

this set the requested permissions.

2. Facebook receives the requested permissions and trans-

lates them into a set of permissions for approval which

we’ll call the granted permissions.

3. Facebook translates the the granted permissions into a

dialogue presented to the user for approval. We’ll call

this text the displayed permissions.

Ideally, these three sets of permissions would be semanti-

cally identical and the text shown to the user would clearly

represent them. In this section we’ll explore the difference

between the requested and granted permissions; we’ll com-

pare displayed and granted permissions in Section 3.

2.1 Methodology

Unfortunately, Facebook’s documentation [3] is incom-

plete and sometimes outdated. As such, there is very lit-

tle explanation of how requested permissions are eventually

translated into permissions displayed to the user. To gain

a better understanding, we combined information from the

documentation with observations from integrating Facebook

Connect login with a test site and crawled data from several

hundred relying sites.

2.1.1 Obtaining a list of relying sites

To obtain a list of relying sites implementing Facebook

Connect, we started with the most recent (October 2013)

AppInspect [18] database of 25,000 Facebook apps. We fil-

tered this list down to about 400 apps with an external site

listed on the Facebook App Center. Finally, we manually

idenitified 91 which had a Facebook Connect login.

Unfortunately, the AppInspect database does not include

apps that are used solely for Facebook Connect, only those

https://www.facebook.com/dialogue/oauth?app_id=138615416238413

&domain=www.timecrunch.me&response_type=token%2Csigned_re

quest&scope=email%2Ccreate_event%2Coffline_access%2Cuser_gr

oups%2Cfriends_groups%2Cpublish_stream...

Figure 2: Example requested permissions (colored in red) in

the scope parameter of the approval page URL.

that have native Facebook apps. To make up for these defi-

ciencies, we took the Alexa Top 500

2

websites from Febru-

ary 27

th

, 2014 and manually identified those with Facebook

Connect logins (112 sites). Combining these two lists gave

us a total of 203 sites to study.

For crawling we used OpenWPM [15] a Selenium-based

3

web crawler being developed by the Princeton Center for

Information Technology Policy (CITP). We performed au-

tomated logins to all 203 sites and recorded the requested,

granted, and displayed permissions. 26 of the 203 sites used

an older version of Facebook Connect; we will focus only on

the 177 using the current version.

2.2 Requested permissions

Developers request permissions in a parameter called

“scope” or “data-scope” when the login process is initiated

using Facebook’s JavaScript SDK, Facebook’s login button,

or a manually built login system [7]. The developer can re-

quest any of the permissions listed in the documentation [6],

although some are deprecated and will have no impact on

the granted permissions.

The scope parameter is visible in the URL of the page

where the user is asked to approve permissions (see Fig-

ure 2). We confirmed using our test site that this value is

indeed exactly what the developer requested.

2.3 Granted permissions

Facebook receives the requested permissions and trans-

lates them into a set of granted permissions. The granted

permissions may exclude requested permissions that are dep-

recated, or, in some cases, may add additional permissions.

Two permissions, which Facebook calls “Basic Info/Default

permissions”[7], are always added regardless of what is re-

quested: public profile and user friends. The documenta-

tion does not mention any other permissions that may be

granted outside of what the developer requested.

2

http://www.alexa.com/topsites

3

https://github.com/cmwslw/selenium-crawler

<input type=“hidden” autocomplete=“off” name=

“read” value=“email,user_groups,friends_groups,

public_profile,user_friends,private” />

<input type=“hidden” autocomplete=“off” name=

“write” value=“publish_stream,publish_actions,

create_note,photo_upload,publish_checkins,share_item,

status_update,video_upload” />

<input type=“hidden” autocomplete=“off” name=

“extended” value=“create_event,rsvp_event” />

Figure 3: Example granted permissions (colored in red)

shown by the read, write, and extended input elements on

the permissions approval page for timecrunch.me.

Read Permissions

user activities, user about me

friends activities, friends about me

email, contact email

read stream, export stream

Write Permissions

create note, upload photos, upload videos,

publish actions, publish checkins, publish stream,

share item, status update

Extended Permissions

rsvp event, create event

Table 1: Groups of permissions which area always granted

together if any are requested.

The approval page presented to the user has three hid-

den input HTML elements named read, write, and extended

whose values are the granted permissions (see Figure 3). We

confirmed with our test site that these permissions are actu-

ally granted and may be used by the relying site, regardless

of the requested permissions.

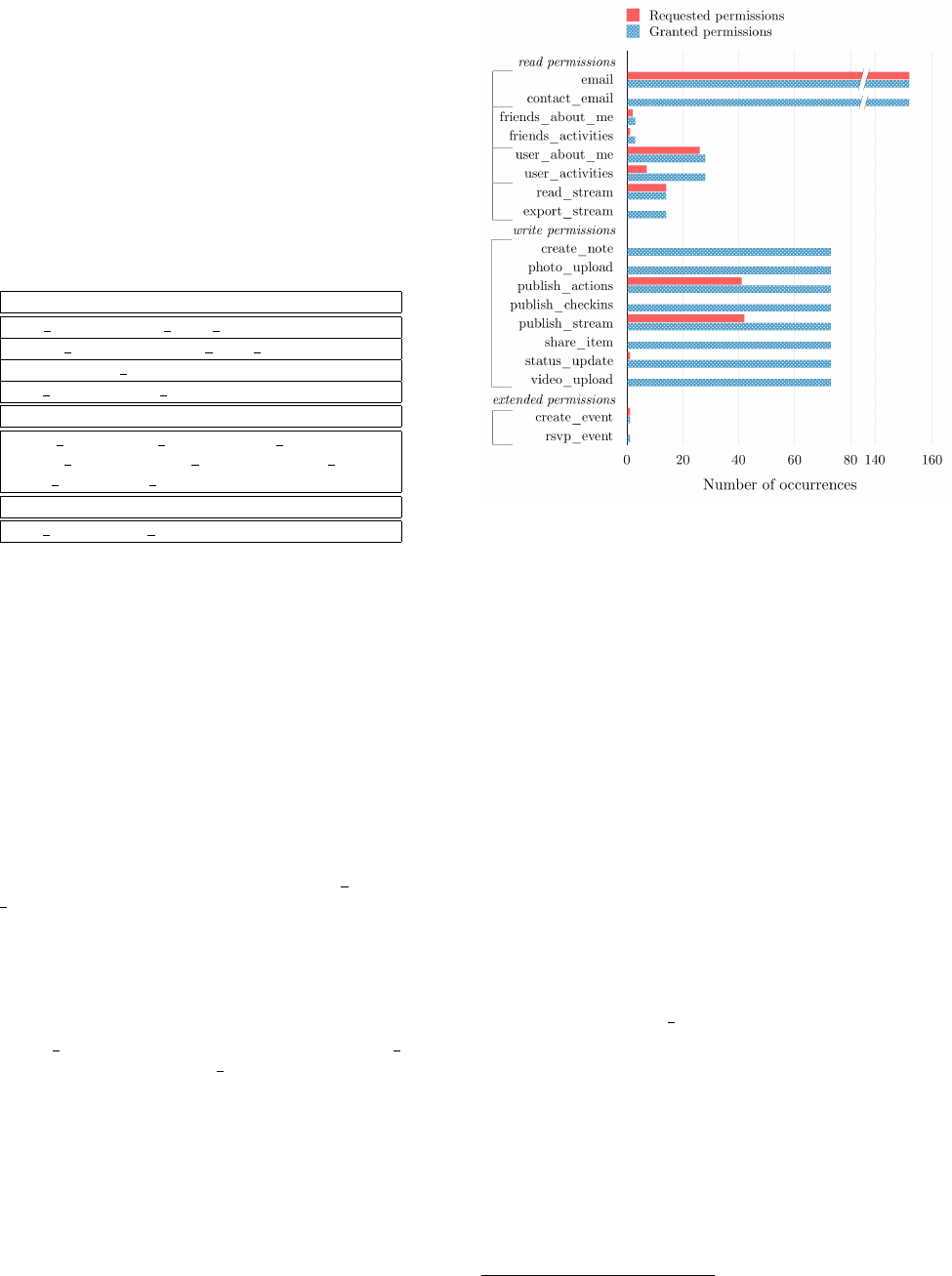

We used these hidden elements to determine which per-

missions were granted in contrast to which were requested

for all 177 sites we crawled. Our results are shown in Fig-

ure 4. First, we confirmed that with every site crawled

the aforementioned default permissions (public profile and

user friends) always appear in granted read permissions al-

though they were never requested.

In addition, we identified several requested permissions

which always cause extra permissions to be granted along

with them (these will be discussed in more detail in the Sec-

tion 2.3). For example, Facebook’s documentation states

that publishing a story (such as liking an article) requires

the publish actions permission. However, if the create note

permission is requested, publish actions will also appear as

a granted permission and this will allow stories to be pub-

lished. Through experimentation with our test site, we de-

termined exactly which permissions are always grouped to-

gether, listed in Table 1. If any one permission in a group is

requested, all permissions in the group are granted. Grouped

permissions are always displayed to the user with a single

message, which we will discuss further in Section 2.4.

All of the grouped read and extended permissions are in

pairs, so if the developer requests one they receive the other.

However, all eight write permissions are in a single group,

effectively making write permissions all-or-nothing.

Figure 4: Permissions requested vs. permissions granted for

permissions granted in groups, as listed in Table 1.

2.4 How permissions are presented to the user

As mentioned previously, when the user logs in to a site

with Facebook Connect for the first time they are presented

with up to three messages from Facebook asking them to

approve the read, write, and/or extended permissions. We

reverse-engineered the algorithm for generating the phrase

or word in the displayed permissions message that corre-

sponds to each granted permission using our test site and

verified that it matched the data observed in our crawl. Most

messages appear reasonably clear. However, the grouped

permissions (see Table 1) are displayed with just one corre-

sponding word or phrase indicating that all the permissions

in that group are being requested. Table 2 presents these

potentially unclear messages and their meaning according to

the Facebook Connect documentation [6]. Similar tables for

all permissions can be found in Appendix A.

2.5 Facebook’s response

We sent a security bug report to Facebook stating that

we could use the publish actions permission after requesting

any other write permission. Facebook Security stated

4

that

“this behavior is by design” and confirmed that when one

permission is requested in the scope, they “translate them

to a broader set of [permissions] which are easier for users

to understand” [1]. When asked why this was done for write

permissions but not read permissions, they responded that

they “made this change to simplify the experience for devel-

opers and for users” and that “write permissions are more

similar...whereas read permissions are more distinct.” This

motivated us to evaluate whether all-or-nothing write per-

missions are in fact easier for the user to understand.

4

Our full correspondence with Facebook is in Appendix C.

Read Permissions: Site Name will receive the following info. . .

Message Permission Meaning [6]

email address

email email

contact email not listed

News Feed

read stream access my News Feed and Wall

export stream

export my posts and make them

public. All posts will be exported,

including status updates.

personal description

user about me about me

user activities activities

...and your friends’. . .

personal descriptions

friends about me ‘about me’ details

friends activities activities

Write Permissions: Site Name would like to. . .

Message Permission Meaning

post to Facebook for you.

– or* –

post publicly to Facebook for you.

– or* –

post privately to Facebook for you.

create note create and modify events

photo upload add or modify photos

publish actions publish my app activity to Facebook

publish checkins publish checkins on my behalf

publish stream publish content to my Wall

share item share items on my behalf

status update update my status

video upload add or modify videos

Extended Permissions: Site Name would like to. . .

Message Permission Meaning

manage your events

create event create and modify events

rsvp event RSVP to events

Table 2: Message decoder for permissions that are granted in groups. Decoder tables for all permissions are in Appendix A.

Italic text represents how the permissions are introduced when presented to the user. See Figure 1 for an example.

*Which of the three messages is presented depends on to whom the posts will be visible. This is controlled by the menu in

the bottom left of the middle image in Figure 1.

3. USER UNDERSTANDING

The second critical component in effective user control on

Facebook Connect is users’ comprehension of the messages

describing the permissions they’re asked to approve. This is

especially important given our findings in Section 2 that

all write permissions are grouped together and displayed

with a single somewhat-vague message. Previous research

by Egelman [14] found that 88% of users have a general un-

derstanding of Facebook’s read permissions dialogues; how-

ever, he studied only the read permissions dialogues. To

our knowledge this is the first study evaluating comprehen-

sion of write permissions. Together with read permissions

these make a fascinating natural experiment: are users bet-

ter able to understand granular (but complicated) read per-

missions, or simpler (but vaguer) write permissions? To test

this and other aspects of user comprehension, we ultimately

conducted three studies:

1. One study tested general comprehension of read and

write permissions and compared them to each other

(see Section 3.2).

5

2. One study tested how site identity affects interpreta-

tion of the write permissions message (see Section 3.3).

5

We decided not to test extended permissions since they are

presented similarly to read permissions and are relatively

rare (only seven out of the 177 sites requested them).

3. Our final study tested to see if users understand that

they are giving access to data regardless of their profile

privacy settings (see Section 3.4).

3.1 Methodology

We conducted our surveys using Amazon Mechanical

Turk, a service where workers can be paid to complete sim-

ple online tasks. This allowed a large and reasonably di-

verse response pool for little cost (we paid 10-15 cents per

response). (See Section 3.5 for a discussion of Mechanical

Turk’s limitations.) All of our surveys took the basic format

of presenting users with real dialogues that they might see

when logging in to a site using Facebook Connect and ask-

ing questions about what actions that site may take if they

authorize the login.

3.1.1 Pilot studies

We piloted three different methods of testing user compre-

hension. After verifying that the respondent had previously

seen a Facebook Connect login, all pilots began by present-

ing the respondent with either a read or write permissions

message that they might see when using Facebook Connect.

No respondents were presented with both to ensure that no

one got the two questions mixed up. Respondents were then

presented with one of the following three question types:

1. A yes/no question asking if the site would be able to

do something if they clicked okay, such as view their

photos or update their status.

2. A list of things the site might be able to do if they

clicked okay. The user was asked to select all those

they thought the site would be able to do.

3. A free response question asking the user to describe

what information they thought the site would be able

to do if they clicked okay.

The free response question has the advantage of not

prompting the user with any ideas that may not have oc-

curred to them otherwise. However, pilots showed that an-

swers to free response questions were frequently too vague

to be useful and that respondents may not have put enough

thought into their answers. While this may reflect how users

pay little attention to permissions messages in real life when

they log in to sites, it is not useful for this survey. There

was no noticeable difference in responses between the yes/no

questions and the multiple-selection questions, so we chose

the latter to get results about more permissions.

We also experimented with showing the respondent mes-

sages from different sites. There was some indication that

the site influenced the responses. For example, people ap-

peared more likely to think photo-oriented sites like Flickr

would be able to do photo-oriented things, such as uploading

photos. To keep our independent variables separate, we con-

ducted two different surveys. The first survey (Section 3.2)

used the site name“Hooli.com”(Hooli is a fake tech company

in HBO’s Silicon Valley). The description of the site given to

users was a description of a real site, Splashscore.com. This

was one of the sites piloted and we determined it had an

appropriately general-sounding description and could con-

ceivably need a wide variety of permissions. The way the

site was presented to users can be seen in Appendix B. Our

second survey (Section 3.3) was designed to test write per-

mission comprehension across different sites.

3.2 Read vs. write permissions

Our first study tests general comprehension of read and

write permissions in such a way that they can be di-

rectly compared. For all questions, we used the site name

“Hooli.com” to eliminate the site name as a variable. Our

tests were designed to evaluate the the following null hy-

potheses:

Null Hypothesis 1. Respondents’ ability to identify which

read permissions they are authorizing is no different than if

they were randomly guessing.

Null Hypothesis 2. Respondents’ ability to identify which

write permissions they are authorizing is no different than if

they were randomly guessing.

Null Hypothesis 3. Respondents’ ability to identify which

read permissions they are authorizing is no different than

their ability to identify which write permissions they are au-

thorizing.

This survey was taken by 600 Mechanical Turk workers.

All were first asked if they had seen a site use Facebook

login before—nearly all had. Half of those who had

6

were

presented with Facebook’s standard write permissions mes-

sage followed by 13 options of things they might be giving

6

Respondents who had not seen a Facebook Connect login

were not given the rest of the survey and were excluded from

analysis, but were still paid for their participation.

the site permission to do by clicking okay. Eight of the 13

were taken almost directly from the Facebook Connect doc-

umentation’s permission descriptions [6], so they were all

things the site would be able to do (since Facebook gives all

write permissions together). The other five were things the

site could not do. They were present not to be tested but to

eliminate biases due to an aversion to selecting all available

options. The 13 options were presented in 4 different orders

and can be seen in Appendix B.3.

The other half were presented with read permissions

questions. Since read permissions messages vary, we

used messages taken from four different real sites with

varying numbers of permissions (Jabong.com, Flickr.com,

Splashscore.com, and TripAdvisor.com). All were renamed

“Hooli.com.” Each message was followed with eight or nine

options for things the site might be able to do. Four or five

options were information on a Facebook profile that the site

would be able to see. The other four were either things the

site could not see or were write or extended permissions.

7

Again, the incorrect answers were only so the respondent

did not have to select all options to be correct. The four

different questions can be seen in Appendix B.2. There are

too many different read permissions to effectively test them

all without exhausting the respondents with too many ques-

tions, so the ones tested are some of the more common ones.

3.2.1 Read permissions results

Figure 5 illustrates the percentage of people who correctly

identified that each permission would be given to the re-

questing site after they clicked okay.

8

Table 3 lists the nu-

merical percentages as well as the 2-tailed p-value from a

binomial test comparing the number of people who correctly

identified a permission as being requested to the expected

value with random guessing: half of the total number of

people who were presented with that permission.

For all tested read permissions, over half of people cor-

rectly identified that said permission would be granted based

on the message presented. On average, individual permis-

sions were correctly identified 79.72% of the time. This is

comparable to Egelman’s [14] conclusion that 88% of users

understand generally which permissions are being requested.

Null Hypothesis 1, that respondents’ ability to identify

which read permissions they are authorizing is no different

than if they were randomly guessing, can be rejected for all

but two permissions with p < .01, suggesting that users have

a significantly better understanding of which read permis-

sions they are granting than if they were randomly guessing.

We can also reject the possibility that users simply marked

every survey option as visible to the website: an average of

81.96% of users correctly identified each of the options that

would not be visible to the site. Null Hypothesis 1 for each

of these options can be rejected with p < .01.

Null Hypothesis 1 for “see what language you speak” can

be rejected with p < .03 and for “see your wall”with p < .05.

A G-test

9

shows that respondents were worse at identifying

7

It is difficult to determine what the site cannot see since

the user’s public profile could contain a lot of information

if they have relaxed privacy settings, so only very clear-cut

things like seeing private messages could be used.

8

Only the real permissions being requested are presented.

The incorrect answers we made up are not.

9

The G-test is a likelihood-ratio statistical test of indepen-

dence applicable in the same cases as a χ

2

-test, but with

Figure 5: Percentage of people who correctly identified that

each read permission would be granted to the site upon au-

thorization.

Permission N

Percent

Correct

2-tailed

p-value

see the cities your

friends live in

78 80.77 0.000

see your friends’ photos 78 76.92 0.000

see what you’ve liked 78 88.46 0.000

see your status updates 150 77.33 0.000

see which city you live

in

230 89.13 0.000

see your wall 72 62.50 0.044

see your gender 72 79.17 0.000

see your News Feed 72 81.94 0.000

see who your family

members are

80 67.50 0.002

see your relationship

status

80 85.00 0.000

see your exact age 159 71.70 0.000

see where you’ve

previously worked

80 83.75 0.000

see who your friends are 79 84.81 0.000

see what language you

speak

79 63.29 0.024

see what country you

live in

79 65.82 0.007

Table 3: p-values for 2-tailed binomial test comparing the

number of people who correctly selected each permission to

Null Hypothesis 1 of random guessing.

“see your wall”than “see your status updates” (which had an

accuracy rate roughly equal to the average) with p < .04 and

a G-test statistic of 4.528. Recall that seeing one’s Wall and

seeing one’s News Feed are both granted by the read stream

permission but the message presented to the user says only

“News Feed” (see Section 4.1). This may have been the

cause of some confusion. Respondents were also worse at

lower approximation error in nearly all cases than the more

traditional Pearson’s χ

2

-test.

Figure 6: Percentage of people who correctly identified that

each permission would be given to the site upon authoriza-

tion.

Permission

Percent

Correct

2-tailed

p-value

update your status 34.88 0.000

publish app activity to

Facebook

45.85 0.166

add and modify photos 8.64 0.000

add and modify videos 8.97 0.000

publish checkins at locations 12.62 0.000

create and modify notes 5.65 0.000

share items with others 34.88 0.000

publish content to your wall 55.81 0.050

Table 4: p-values for 2-tailed binomial test comparing the

number of people who correctly selected each permission to

Null Hypothesis 2 of random guessing. N = 301 for all

permissions.

identifying “see what language you speak” with p < .04 and

a G-test statistic of 4.338, but the reason for this is unclear.

3.2.2 Write permissions results

Figure 6 illustrates the percentage of people who correctly

identified that each permission would be given to the re-

questing site after they clicked okay. Table 4 lists the nu-

merical percentages as well as the 2-tailed p-value from a

binomial test comparing the number of people who correctly

identified a permission as being requested to Null Hypothe-

sis 2, that user’s understanding would be equivalent to ran-

dom guessing.

For all permissions except for “publish content to your

wall,” fewer than half of respondents answered correctly. For

all of those except “publish app activity to Facebook,” Null

Hypothesis 2, that respondents’ ability to identify which

write permissions they are authorizing is no different than if

they were randomly guessing, can be rejected with p < .01.

That is, for these six permissions, people would have been

significantly more likely to correctly identify whether they

were granting the permission by randomly guessing.

The p-value for “publish app activity to Facebook” is too

high to reject Null Hypothesis 2 with a reasonable level of

confidence.

Over half of people correctly identified that the site would

be able to “publish content to [their] wall,”and Null Hypoth-

esis 2 can be rejected with p < .05. People may have a better

idea that this permission is being granted than if they were

randomly guessing.

Worth noting is that the two permissions people did best

with (“publish content to your wall” and “publish app ac-

tivity to Facebook”) are also the vaguest. (These are the

publish stream and publish actions permissions that are in-

tended to give nearly all publishing permissions.) Because

they are so vague, the fact the more people selected them

correctly probably does not mean that they fully understand

the specific things the site can post on their profile—they

include the functions of the other permissions, which most

users were not successful at identifying.

3.2.3 Comparison of read and write permissions

It appears evident at this point that users understand

read permissions messages significantly better than they

understand write permissions messages: Respondents cor-

rectly identified whether a read permission would be granted

79.72% of the time, whereas write permissions were only cor-

rectly identified 25.91% of the time.

To evaluate Null Hypothesis 3, that respondents’ ability

to identify which read permissions they are authorizing is

no different than their ability to identify which write per-

missions they are authorizing, we assigned a ranking to each

respondent based on the percentage of permissions they cor-

rectly identified

10

and separated them into two groups, one

for those asked about read permissions and one for those

asked about write permissions. A Mann-Whitney U test of

these two groups allows us to reject Null Hypothesis 3 with

p < 0.001 and a test statistic of U = 9163.

3.3 Influence of relying site

As previously mentioned, our pilot surveys indicated that

the site identity may influence how people interpret the write

permissions message. We performed a separate survey with

300 Mechanical Turk workers to test this. The format of

the survey was identical to the write permissions questions

in the first survey and we provided the same options for the

user to select. However, instead of using “Hooli.com” as the

website in question, one third of respondents were presented

with Flickr.com (a photo and video sharing site), one third

with TripAdvisor.com (a travel site), and one third with

iFlikeU.com (an anonymous messaging site). (Since there is

only one write permissions message, the message presented

to the user in all cases was identical aside from the site name

and description.)

The results of this survey can be statistically analyzed

with a G-test to see if the number of respondents who

thought each permission would be granted varied across

the four sites (the three mentioned here plus the data from

“Hooli.com” from the first survey). Our null hypothesis is:

Null Hypothesis 4. The relying site’s identity does not

affect how respondents interpret a requested permission.

3.3.1 Results

Figure 7 illustrates the percentage of people who correctly

identified that each permission would be given to each site

after they clicked okay. Table 5 lists the numerical percent-

ages as well as the p-values from a G-test comparing the

variation in number of correct selections for each permission

across all four sites.

For “publish app activity to Facebook,”“add and modify

photos,”“add and modify videos,” and “publish checkins at

10

This counts only the real permissions and not the incorrect

options since those were artificially created.

Figure 7: Percentage of people who correctly identified that

each permission would be given to the site upon authoriza-

tion for four sites.

locations,” Null Hypothesis 4, that the relying site’s iden-

tity does not affect how respondents interpret a requested

permission, can be rejected with p < .01. More respondents

thought Flickr would be able to add and modify photos and

videos compared to other sites, which is reasonable since it is

a photo and video sharing site. Likewise, many more people

thought that TripAdvisor would be able to publish checkins

at locations—a logical thing for a travel site to do.

Null Hypothesis 4 can be rejected for “update your sta-

tus” with p < .04 and “publish content to your wall” with

p < .05. It cannot be rejected for “share items with oth-

ers” nor “create and modify notes” with a reasonable level of

confidence.

3.4 Influence of privacy settings

In one pilot survey of the free response format, a respon-

dent stated that the site would gain access to only a limited

number of permissions because their Facebook settings pre-

vented them from accessing the rest. This suggests a lack

of understanding of how the read permissions work: A site

can access nearly everything that is public with only the

public profile permission [9]. By granting the site additional

permissions, a user is giving the site permission to access

that information regardless of the user’s privacy settings.

Using the test site, we confirmed that we could see all user

photo albums regardless of their privacy settings with the

user photos permission.

We surveyed 100 additional Mechanical Turk respondents

to see if this confusion was widespread. The survey pre-

sented the user with the permission message for Imgur.com,

which requests the user photos permission. Users were asked

to identify which photo albums Imgur would be able to see

if they clicked okay. The options were those marked as vis-

ible to the public, those marked as visible to friends, and

those marked as visible to only them (the correct answer is

all three). The survey can be seen in Appendix B.4.

Our null hypothesis in this experiment is:

Null Hypothesis 5. Respondents are equally likely to in-

dicate that data can be read regardless of its privacy setting.

Permission

Percent Correct G-test

statistic

p-value

Flickr

(N = 100)

TripAdvisor

(N = 93)

iFlikeU

(N = 102)

Hooli

(N = 301)

update your status 34 20.43 24.51 34.88 8.662 0.034

publish app activity to Facebook 64 51.61 35.29 45.85 16.733 0.001

add and modify photos 22 7.53 4.90 8.64 15.185 0.002

add and modify videos 15 2.15 3.92 8.97 11.783 0.008

publish checkins at locations 11 24.73 6.86 12.62 10.937 0.006

create and modify notes 6 3.23 11.76 5.65 4.783 0.188

share items with others 31 32.26 30.39 34.88 0.706 0.872

publish content to your wall 65 53.76 44.12 55.81 8.208 0.042

Table 5: p-values for G-test comparing the number of people who correctly selected each permission across four sites to Null

Hypothesis 4 of no difference between sites.

Figure 8: Percentage of people who correctly identified that

Imgur.com would be able to see their photo albums of each

privacy level upon authorization.

3.4.1 Results

Figure 8 illustrates the percentage of people who correctly

identified that Imgur.com would be able to see their photo

albums with various privacy settings if they clicked okay. It

appears people are generally aware that they are giving ac-

cess to their photo albums that are marked as public. How-

ever, they are generally unaware that they are also giving

access to their photo albums that are marked as visible to

their friends or only to themselves.

Using a G-test with three degrees of freedom to compare

all three test conditions, Null Hypothesis 5, that respondents

are equally likely to indicate that data can be read regard-

less of its privacy setting, can be rejected with p < .001

based on a G-test statistic of 86.31. Comparing each pair of

conditions in turn using a G-test with two degrees of free-

dom, we can conclude with p < .001 that participants were

significantly more likely to believe photos marked “visible to

the public” could be read than either photos marked “visi-

ble to friends” or “visible to only me”. However, we cannot

conclude with high confidence (p ≈ .12) that participants

were significantly more likely to believe photos marked “vis-

ible to friends” could be read than photos marked “visible to

only me”. Thus we can reject Null Hypothesis 5 in general

and conclude that users do believe privacy settings impact

visibility of data to third-party sites, we cannot conclude if

the specific privacy settings (visible to friends or only to the

user) had a significant impact on user understanding.

Although our first set of surveys and Egelman’s study

[14] indicated that read permissions are understood decently

well, this study suggests that these results may not actually

be entirely representative of user understanding: although

people know which types of information they are granting

access to, most do not realize they are giving access to that

information even if they have marked it with a privacy level

other than public.

3.5 Limitations

There are several possible limitations to our surveys:

• As discussed previously, by giving respondents several

options to select we suggested possible things the site

could do that may not have occurred to them other-

wise. In addition, in order to respond to our questions

they may have paid more attention to the permissions

dialogues than they normally would have. As a result,

our survey may indicate that users are more aware of

what permissions are being requested than they are in

practice.

• If read and write permissions are fundamentally dif-

ferent in some non-obvious way, it may be invalid to

compare understanding of read permissions to under-

standing of write permissions. It is possible that users

would understand write permissions even more poorly

if they were presented granularly rather than all-or-

nothing.

• There may be some demographic bias in using Me-

chanical Turk to collect responses. We did not collect

demographic information from respondents although

we did restrict respondents to the United States (this

was the only restriction we placed on respondents).

Our use of Mechanical Turk is justified by previous

research finding that “[Mechanical Turk] participants

produced reliable results that are consistent with pre-

vious decision-making research” [17]. The most rele-

vant concern they raise is of respondents not paying

enough attention and becoming fatigued in longer sur-

veys; the short length of our surveys hopefully ame-

liorated that to some degree. In addition, users are

known to pay little attention to permissions messages

in practice [14].

• When asking users which permissions were being

granted, we had to make up some fake options so users

did not have to select every option to be correct. If

we did a poor job, this could have influenced results

by distracting or unsettling users. We did not count

these made up permissions in our statistical analysis

for this reason.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study indicates that users have a decent understand-

ing of read permissions messages but a significantly worse

understanding of write permissions messages. As discussed

in Section 2.5, Facebook claims that all-or-nothing write

permissions are easier for the user to understand. However,

comparison with the very granular read permissions suggests

that users understand specific, distinct permissions better.

We also observe that grouped permissions cause confu-

sion for developers who may receive more permissions than

intended due to grouping of permissions. This appears con-

trary to Facebook’s stated advice to developers that they

should “only ask for the permissions that are essential to

an app [or site]” [7]. Facebook’s own research has demon-

strated that “the more permissions an app requests, the less

likely it is that people will use Facebook to log into [that]

app”[7]. But because Facebook Connect often grants more

permissions than the developer requested (even just by al-

ways granting public

profile and user friends), the developer

may have no choice but to receive unnecessary permissions.

We consider several possible explanations for why the sys-

tem may be architected this way.

4.1 Evolution over time

Some of our findings around the permissions API appear

likely to be artifacts of the API’s evolution, many of which

appear harmless. For example, two permissions for read-

ing an email address exist (email and contact email) and

grouping them seems sensible.

It appears that the reason that all write permissions are

presented together is that Facebook is gradually eliminating

the distinction between different types of publishing under

the hood. The description in the documentation for pub-

lish actions is “publish my app activity to Facebook” and

the description for publish stream is “publish content to my

Wall” [6]. These are quite vague, and seem as though they

could encompass nearly anything. A blog post from a Face-

book employee [12] helps explain these permissions: They

are essentially the same thing (and are being merged into

one) and allow a site to do any type of publishing to Face-

book. The post mentions that they can be used to up-

load a photo, which one may have suspected required the

photo upload permission. Another post from a Facebook

employee mentions that developers should only request pub-

lish actions because it encompasses all other write permis-

sions in an effort to “simplify the model” [27]. Furthermore,

Facebook’s Graph API lists publish actions as the permis-

sion needed for all API calls that involve publishing [5].

This transition towards only one type of publishing is vis-

ible to anyone who has used Facebook for several years: up-

dating one’s status and uploading a photo used to be distinct

actions, but now they are both performed by creating a post

on one’s Timeline. Perhaps at one point the six granular

write permissions (create note, upload photos, upload videos,

publish checkins, share item, status update) were the only

write permissions. The read and extended permissions that

are presented in groups may stem from similar changes in

Facebook’s structure and it may no longer be possible to

separate them.

It is understandable that changes in the structure of Face-

book necessitate changes in the Facebook Connect API to

keep it simple and consistent. However, our results sug-

gest user control may significantly harmed for the sake of

simplicity. This threat does not appear purely academic,

as there are many malicious Facebook apps that abuse the

permissions they are given [13, 21].

4.2 Privacy salience

It is also possible that Facebook has evolved towards hav-

ing a vague write permissions message as a strategy to de-

crease privacy salience [10]. If users thought too many per-

missions were being granted, they may not use the app or

the Facebook Connect platform in general. A vague mes-

sage allows developers to receive more permissions without

losing users.

Evidence that this may be Facebook’s intention can be

seen by comparing the current write permissions messages to

those from the previous implementation of Facebook Con-

nect. As mentioned previously, 26 of the 203 websites we

crawled used an older implementation. Table 6 presents

a sampling of the messages we saw. These messages may

be misleading since they provide examples of what the site

can post based on the specific site even though all sites in

the table request only publish actions. However, these mes-

sages do distinctly identify several things the sites can post,

unlike the vague messages in the current implementation.

Facebook’s choice to eliminate these descriptions may indi-

cate an attempt to be less clear about what permissions are

actually being granted.

By itself, limiting privacy salience cannot be a complete

explanation because read permissions remain relatively de-

tailed. It may be that read permissions are less concerning

to users as write permissions can affect the user’s profile on

Facebook itself, so Facebook is less motivated to obscure

them. Alternatively, it may be the case that read permis-

sions are in fact more sensitive, since data cannot be un-read

whereas unwanted posts from a third-party can be deleted.

In this case, it may be that Facebook has decided that its

more important to clearly indicate read permissions up front,

whereas it isn’t worth concerning users with detailed write

permissions since posts can be deleted later.

Site

Write Permissions

Message

Starpires.com

This app may post on your

behalf, including status

updates, photos and more.

PioneerLegends.com

This app may post on your

behalf, including collections

you completed, miles you

collected and more.

Stratego.com

This app may post on your

behalf, including achievements

you earned and more.

OpenShuffle.com

This app may post on your

behalf, including your high

scores and more.

Fupa.com

This app may post on your

behalf, including games you

played and more.

Table 6: Write permissions messages from sites using an

older version of Facebook Connect. All sites are gaming

sites. The only write permission requested is publish actions.

4.3 Ineffectiveness of user choice

It is possible that write messages are vague because users

are unable to completely understand them (or simply do not

pay attention to them [14]), so Facebook has decided it is

better off protecting user privacy by policing developers.

Facebook has publicly attempted to address how general

write permissions are by placing responsibility on the de-

veloper. The aforementioned Facebook blog post explain-

ing the publish stream and publish actions permissions [12]

states that since anything can be shared, “it will continue to

be the developer’s responsibility to make it clear to the user

what content will be shared back to Facebook.” Facebook’s

policy was updated to read: “If a user grants [the developer]

a publishing permission, actions [the developer takes] on the

user’s behalf must be expected by the user and consistent

with the user’s actions within [the] app.” This is especially

important since our survey showed that users’ interpretation

of the write permissions message is influenced by the identity

of the site even though there is no difference in the permis-

sions being granted. As of the time of this writing, however,

this is no longer mentioned in the Facebook policy [8].

5. FUTURE AREAS FOR RESEARCH

This research could be extended in a number of directions.

• The results of our survey testing whether users under-

stand that sites are getting access to their information

even if it is marked as private (see Figure 8) indicate

that there is room for more research in the area. This

should be tested with a variety of different permissions.

One could also experiment with ways to make it clear

to the user that all of their information is being shared,

regardless of the privacy settings.

• We previously mentioned that our survey included op-

tions of things the sites could not actually do so the

respondent would not have to select all options to be

correct. However, many people selected these fake op-

tions. One could research what permissions users think

are being requested beyond what is actually being re-

quested. This is an important area of research because

people may be unwilling to use the SSO service if they

think too many permissions are being given.

• It is clear that users do not understand the full range

of write permissions being requested. However, Egel-

man [14] determined that users make their decision

to use Facebook Connect or not before they see the

permissions requested. Egelman only tested read per-

missions, though. A similar study could see how the

presence of write permissions affects users’ decisions to

use Facebook Connect.

• We observed that users understand the granular read

permissions better than the single write permission.

One could test whether granular write permissions are

in fact more clear to users than the current system.

6. RELATED WORK

Many researchers have studied the security and permis-

sions systems of various apps

11

and SSO systems. Sun

and Beznosov [24] uncovered vulnerabilities in many ma-

jor OAuth SSO implementations. Chaabane et al. [11] and

11

The Facebook Connect SSO system uses the same system

as native Facebook apps—creating a Facebook login on a

website requires creating a Facebook app [4].

Huber et al. [18] identified information leaks in Facebook

and RenRen apps. There have also been several studies of

what permissions sites request, such as Frank et al.’s study

in which Facebook apps were grouped into categories based

on the permissions they request [16].

Some studies have tested user comprehension of SSO sys-

tems as well. A 2011 audit of Facebook Ireland looked at,

among other things, how clearly the Facebook app system

is presented to users. It also states that it “is not possible

for an application to access personal data over and above

that to which an individual gives their consent or enabled

by the relevant settings”—that is, Facebook’s permissions

do appropriately limit what data an app can access [2].

Sun et al. studied user understanding of the authentica-

tion process in general—for example, whether users under-

stood that the site they are logging in to cannot see the

password for the identity provider (Facebook, Google, etc.)

[26]. The study most directly related to ours is Egelman

[14], which studied whether users were willing to use Face-

book Connect and how well they understand (and how much

they pay attention to) the permissions messages. Egelman

concluded that 88% of users have a general understanding

that their profile information will be shared with the site

they are logging in to, but that they typically do not pay

attention to the specifics of the dialogues and do not make

their decision whether to use Facebook Connect based on

which permissions are being requested.

Our study differs from previous studies by determining

what specific permissions correspond to the messages pre-

sented to the user and by evaluating user comprehension

of these permissions. This lets us answer most precisely

whether users understand exactly what information they are

sharing by using Facebook Connect. In addition, Egelman

only looked at read permissions. We found that write per-

missions are much more confusing to users.

7. CONCLUDING REMARKS

To maximize security and to ensure users feel comfort-

able using Facebook Connect, developers should minimize

the number of permissions they request and the permissions

should be presented to the user as clearly as possible. On

both fronts, Facebook Connect could be improved.

When a developer designs their site to request certain

permissions through Facebook Connect, the Facebook Con-

nect system may translate certain permissions into broader

groups of permissions that will all be granted if the user au-

thorizes the site to access their profile. This may force users

to give unnecessary permissions to a site in order to log in.

The messages presented to the user for read permissions

are reasonably clear—our survey showed that a majority of

users understand what data they are providing access to.

However, many users are unaware that they are providing

access even if this information is marked as private.

Write permissions, however, are much less clear. Face-

book has simplified the write permissions process so that

every site either gets all write permissions or none. Our sur-

vey shows that users do not understand the many things a

site will be able to do to their profile if they authorize the

vague message stating that the site “would like to post to

Facebook for you.” In addition, users’ interpretations of this

message vary depending on the identity of the site they are

logging in to although this actually has no impact on the

permissions granted. Given the relative success with which

users were able to identify the more distinct and well-defined

read permissions, it appears users might actually understand

write permissions better if they were split up.

On April 30, 2014 Facebook announced an update to their

Facebook Login system to be rolled out over the following

months that allows users to reject individual permissions or

log in anonymously [23]. While this is a big step forward, it

appears there is still only one publishing permission and it

is presented with the same vague message that our survey

respondents had trouble understanding. However, it does

provide even more specific details about read permissions.

8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Arvind Narayanan for starting us on this re-

search path. Thanks to Steven Englehardt, Dillon Reisman,

Pete Zimmerman, and Christian Eubank for setting us up

with the CITP’s web crawling infrastructure. Steven orig-

inally discovering permissions in the hidden HTML input

elements. Thanks to Markus Huber for providing us with

the AppInspect dataset [18].

9. REFERENCES

[1] Personal correspondence with Facebook Security

representative (Neal), April 2014.

[2] Report of Data Protection Audit of Facebook Ireland,

December 2011.

[3] Facebook Developer Reference—Facebook Login.

https:

//developers.facebook.com/docs/facebook-login/,

2014.

[4] Facebook Developer Reference—Getting Started with

Custom Stories. https://developers.facebook.com/

docs/opengraph/getting-started/, 2014.

[5] Facebook Developer Reference—Graph API

Reference. https://developers.facebook.com/docs/

graph-api/reference/, 2014.

[6] Facebook Developer Reference—Permissions.

https://developers.facebook.com/docs/

reference/fql/permissions/, 2014.

[7] Facebook Developer Reference—Permissions with

Facebook Login. https://developers.facebook.com/

docs/facebook-login/permissions, 2014.

[8] Facebook Developer Reference—Platform Policy.

https://developers.facebook.com/policy/, 2014.

[9] Facebook Developer Reference—Privacy for Apps &

Websites.

https://www.facebook.com/help/403786193017893,

2014.

[10] J. Bonneau and S. Preibusch. The Privacy Jungle: On

the Market for Privacy in Social Networks. In WEIS

’09: Proceedings of the 8

th

Workshop on the

Economics of Information Security, June 2009.

[11] A. Chaabane, Y. Ding, R. Dey, M. A. Kaafar, and

K. W. Ross. A Closer Look at Third-Party OSN

Applications: Are They Leaking Your Personal

Information? In Passive and Active Measurement

Conference (2014), Los Angeles, March 2014. Springer.

[12] L. Chen. Streamlining publish stream and

publish actions permissions. Facebook Blog, April

2012.

[13] P. H. Chia, Y. Yamamoto, and N. Asokan. Is This

App Safe?: A Large Scale Study on Application

Permissions and Risk Signals. In WWW ’12

Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on

the World Wide Web. ACM, April 2012.

[14] S. Egelman. My profile is my password, verify me!:

The privacy/convenience tradeoff of Facebook

Connect. In CHI ’13 Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

ACM, 2013.

[15] S. Englehardt, C. Eubank, P. Zimmerman,

D. Reisman, and A. Narayanan. Web Privacy

Measurement: Scientific principles, engineering

platform, and new results. 2014.

[16] M. Frank, B. Dong, A. P. Felt, and D. Song. Mining

Permission Request Patterns from Android and

Facebook Applications. In The 12th IEEE

International Conference on Data Mining. IEEE, 2012.

[17] J. K. Goodman, C. E. Cryder, and A. Cheema. Data

Collection in a Flat World: The Strengths and

Weaknesses of Mechanical Turk Samples. Behavioral

Decision Making, 26(3):213–224, 2013.

[18] M. Huber, M. Mulazzani, S. Schrittwieser, and

E. Weippl. AppInspect: Large-scale Evaluation of

Social Networking Apps. In COSN ’13 Proceedings of

the First ACM Conference on Online Social Networks.

ACM, 2013.

[19] D. Morin. Announcing Facebook Connect. Facebook

Blog, May 2008.

[20] H. Nissenbaum. Privacy as contextual integrity.

Washington Law Review, 79, 2004.

[21] M. S. Rahman, T.-K. Huang, H. V. Madhy, and

M. Faloutsos. FRAppE: Detecting Malicious Facebook

Applications. In CoNEXT ’12 Proceedings of the 8th

International Conference on Emerging Networking

Experiments and Technologies. ACM, 2012.

[22] P. Sovis, F. Kohlar, and J. Schwenk. Security Analysis

of OpenID. In Securing Electronic Business Processes

- Highlights of the Information Security Solutions

Europe 2010 Conference, 2010.

[23] J. Spehar. The New Facebook Login and Graph API

2.0. Facebook Blog, April 2014.

[24] S.-T. Sun and K. Beznosov. The Devil is in the

(Implementation) Details: An Empirical Analysis of

OAuth SSO Systems. In Proceedings of ACM

Conference on Computer and Communications

Security ’12. LERSSE, October 2012.

[25] S.-T. Sun, Y. Boshmaf, K. Hawkey, and K. Beznosov.

A Billion Keys, but Few Locks: The Crisis of Web

Single Sign-On. In NSPW ’10: Proceedings of the 2010

New Security Paradigms Workshop. ACM, 2010.

[26] S.-T. Sun, E. Pospisil, I. Muslukhov, N. Dindar,

K. Hawkey, and K. Beznosov. Investigating User’s

Perspective of Web Single Sign-On: Conceptual Gaps,

Alternative Design and Acceptance Model. ACM

Transactions on Internet Technology, 2013.

[27] A. Wyler. Providing people greater clarity and

control. Facebook Blog, December 2012.

APPENDIX

A. FULL MESSAGE DECODING TABLES

Message Permission Meaning [6]

birthday user birthday birthday

chat status user online presence online presence

checkins user checkins checkins

current city user location current city

custom friends lists read friendlists access my friend lists

education history user education history education history

email address

email email

contact email not listed

events user events events

follows and followers user subscriptions subscribers and subscribees

friend list user friends list of friends

friend requests read requests access my friend requests

groups user groups groups

hometown user hometown hometown

interests user interests interests

likes user likes

likes, music, TV, movies, books,

quotes

messages read mailbox read messages from my mailbox

News Feed

read stream access my News Feed and Wall

export stream

export my posts and make them

public. All posts will be exported,

including status updates.

notes user notes notes

personal description

user about me about me

user activities activities

photos user photos photos uploaded by me

public profile public profile not listed

questions user questions questions

relationship interests user relationship details

significant other and relationship

details

relationships user relationships

family members and relationship

status

religious and political views user religion politics religious and political views

status updates user status Facebook status

Video activity user actions.video not listed

videos user videos videos uploaded by me

website user website website

work history user work history work history

Table 7: Read permission message decoder, part (a). Message begins with “Site Name will receive the following info. . . ” See

Figure 1 (left image) for an example.

Message Permission Meaning [6]

birthdays friends birthday birthdays

chat statuses friends online presence online presence

checkins friends checkins checkins

current cities friends location current cities

education histories friends education history education history

events friends events events

follows and followers friends subscriptions subscribers and subscribees

groups friends groups groups

hometowns friends hometown hometowns

interests friends interests interests

likes friends likes

likes, music, TV, movies, books,

quotes

notes friends notes notes

personal descriptions

friends about me ‘about me’ details

friends activities activities

photos friends photos photos

questions friends questions questions

relationship interests friends relationship details

significant others and

relationship details

relationships friends relationships

family members and

relationship statuses

religious and political views friends religion politics religious and political views

status updates friends status Facebook statuses

videos friends videos videos

websites friends website websites

work histories friends work history work history

Table 8: Read permission message decoder, part (b). After listing the permissions that apply to the user, the permissions

applying to their friends are listed. This part of the message begins with “...and your friends’. . . ” See Figure 1 (left image)

for an example.

Message Permission Meaning [6]

Site Name would like to post

to Facebook for you.

– or –

Site Name would like to post

publicly to Facebook for you.

– or –

Site Name would like to post

privately to Facebook for you.

create note create and modify events

photo upload add or modify photos

publish actions publish my app activity to Facebook

publish checkins publish checkins on my behalf

publish stream publish content to my Wall

share item share items on my behalf

status update update my status

video upload add or modify videos

Table 9: Write permission message decoder. See Figure 1 (middle image) for an example. Which of the three messages is

presented depends on to whom the posts will be visible. This is controlled by the menu in the bottom left of the middle image

in Figure 1.

Message Permission Meaning [6]

access your Facebook ads and

related stats

ads read

access my Facebook ads and

related stats

access your Facebook Pages’

messages

read page mailboxes read messages for my pages

access your Page and App

insights

read insights

access Insights data for my pages

and applications

manage your ads ads management

manage advertisements on behalf

of me

manage your custom friend lists manage friendlists

create, delete, and modify my

friend lists

manage your events

create event create and modify events

rsvp event RSVP to events

manage your notifications manage notifications

may access my notifications and

may mark them as read

manage your Pages manage pages manage my pages

send and receive messages

on your behalf

xmpp login login to Facebook Chat

send you text messages sms send SMS messages to my phone

Table 10: Extended permission message decoder. Message begins with “Site Name would like to. . . ” See Figure 1 (right

image) for an example.

B. SURVEYS

This appendix provides details of the surveys used to test

user understanding of permissions messages. Descriptions of

the survey process can be found in Section 3.

B.1 Initial question

The first question on every survey reads “Some websites

allow you to log in to their site using your Facebook ac-

count. Have you seen this?” If the user answered yes, they

were taken to the rest of the survey. If they answered no,

the survey ended. This was to prevent confusion caused by

seeing permissions messages out of context. Nearly all users

answered yes.

B.2 Read permissions surveys

Figures 9, 10, 11, and 12 show the four different ver-

sions of the survey to test understanding of read permissions.

Each uses the fake site name “Hooli” but the permissions are

taken from a different real site for each. The correct answers

are selected.

Figure 9: A read permissions survey. The correct answers

are selected. This version of the survey uses the permissions

from TripAdvisor.com.

B.3 Write permissions surveys

Figure 13 shows the survey to test understanding of write

permissions. It also uses the fake site “Hooli.” The correct

answers are selected. There were a total of four versions of

this survey with the options in different orders.

Figure 10: A read permissions survey. The correct answers

are selected. This version of the survey uses the permissions

from Splashscore.com.

B.4 Additional read permissions survey

Figure 14 shows the survey to test whether users under-

stand that they are giving access to their information that

is not marked as visible to the public. The correct answers

are selected.

Figure 11: A read permissions survey. The correct answers

are selected. This version of the survey uses the permissions

from Jabong.com.

Figure 12: A read permissions survey. The correct answers

are selected. This version of the survey uses the permissions

from Flickr.com.

Figure 13: A write permissions survey. The correct answers

are selected.

Figure 14: The additional read permissions survey. The

correct answers are selected.

C. CORRESPONDENCE WITH FACE-

BOOK SECURITY

As mentioned in Section 2.5, we sent a security bug report

to Facebook reporting that we could use the publish actions

permission after requesting any other write permission (see

Section 2.3). Below is the full correspondence with Facebook

Security [1].

Initial bug report

Description and Impact:

I can design a site with Facebook Connect that publishes

a story with the ‘publish actions’ permission. However, if I

request any other write/publishing permission, such as ‘cre-

ate note’, I can still use the ‘publish actions’ permission and

publish the story. I believe this is a vulnerability because

applications may be receiving more capability than they be-

lieve they are requesting.

Reproduction Instructions / Proof of Concept:

1. I followed the Facebook documentation instruc-

tions to create a story with the publish actions

permission: https://developers.facebook.com/docs/

opengraph/getting-started/

2. If I replace publish actions in data-scope with any other

write permission, including create note, I can still pub-

lish the story. (If I replace it with a read permission

such as email I cannot.)

Facebook Security’s response

Thanks for writing in. Can you send in some screenshots of

the dialogue you see when requesting the different permis-

sions? I’m curious to see if the wording changes between the

two.

Our response

Below are screenshots of the two messages presented whether

I request create note or publish actions. [screenshots not

shown here, roughly equivalent to Figure 1, center image]

The HTML for these messages has three hidden input

elements named read, write, and extended. The permis-

sions requested appear in their value fields. However, if

I request any of the 8 write permissions (publish actions,

publish stream, status update, video upload, photo upload,

share item, create note, or publish checkins), all 8 appear in

the value of the input element named write. I’ve been re-

searching this for a class project at Princeton University and

I’ve confirmed that this is true on 73 of 73 different websites

that request write permissions. The only two write permis-

sions messages between the 73 sites are “App Name would

like to post to Facebook for you” and “App Name would like

to post publicly to Facebook for you.” The presence of “pub-

licly” is just determined by the selection on the menu on the

bottom left of the message page (second screenshot), not by

the permissions being requested.

Facebook Security’s response

I’ll confirm with the Platform team, but I believe this is

intentional behavior: as you noted, while in the URL you’re

requesting one scope we actually translate them to a broader

set of scopes which are easier for users to understand.

Facebook Security’s followup

I just confirmed with our Platform team that this behavior

is by design.

Our response

Ok, thanks for looking into that. Is there a reason you do

that for the write permissions but not for read or extended

permissions?

Facebook Security’s response

The Platform team made this change to simplify the ex-

perience for developers and for users. My guess would be

that generally, write permissions are more similar (ie: cre-

ating a note versus creating a video versus posting all are

ways to create content on the site that are not very differ-

ent) whereas read permissions are more distinct (ie: an app

which can view your friends does not necessarily need to

view your relationships unless major functionality changes).

[End of correspondence]