HAL Id: hal-04027333

https://hal.science/hal-04027333

Submitted on 13 Mar 2023

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives 4.0

International License

The eect of colors of e-commerce websites on consumer

mood, memorization and buying intention

Jean-Éric Pelet, Panagiota Papadopoulou

To cite this version:

Jean-Éric Pelet, Panagiota Papadopoulou. The eect of colors of e-commerce websites on consumer

mood, memorization and buying intention. European Journal of Information Systems, 2012, 21 (4),

pp.438-467. �10.1057/ejis.2012.17�. �hal-04027333�

1

THE EFFECT OF COLORS OF E-COMMERCE WEBSITES ON

CONSUMER MOOD, MEMORIZATION AND BUYING

INTENTION

Jean-Éric Pelet

a

& Panagiota Papadopoulou

b

a

Nantes University, Nantes, France,

b

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Abstract

This paper aims at studying the effect of the colors of e-commerce websites on consumer mood,

memorization and buying intention. Based on a literature review a conceptual model is proposed,

showing the effects of the color of e-commerce websites and specifically of its components, hue and

brightness on the behavioral responses of the consumer, memorization and buying intention. These

responses are conveyed by mood. Data collection was carried out during a laboratory experiment in

order to control for the measurement of the colored appearance of e-commerce websites. Participants

visited one of the 8 versions of a website designed for the research, selling music CDs. Data analysis

using ANOVA, regressions and general linear models (GLM), show a significant effect of color on

memorization, conveyed by mood. The interaction of hue and brightness, using chromatic colors for the

background and foreground supports memorization and buying intention, when contrast is based on low

brightness. A negative mood infers better memorization but a decreasing buying intention. Implications

for theory and practice are discussed.

Keywords: color, consumer behavior, e-commerce, web design, mood, memorization.

2

0BINTRODUCTION

E-commerce website interfaces seek to entice consumers in a buying intention and manifest a buying

behavior, by activating their senses, specifically their sight or hearing. The perception of a website

atmosphere lies almost exclusively in its visual aspect since 80% of the information processed by Internet

user’s brain comes from sight (Mattelart, 1996). Color constitutes an important sight stimulus for online

consumers, since it is a key website characteristic, associated with the information displayed as well as

with the overall website aesthetics. As such, color is deemed as a significant website factor, positively

influencing the frequency of a consumer visiting a website (Lemoine, 2008) and affecting online shopper

responses (Eroglu et al., 2001, 2003).

Although color is a widely researched topic in various fields (Divard and Urien, 2001), to this day there

is a lack of studies focusing on color in the online context. Color in websites has been studied within

information systems, especially in human-computer interaction, usability and e-commerce, recognized as

a fundamental aspect in web interface design (Lee and Koubek, 2010; Wu et al., 2008; Coursaris et al.,

2008; Kang and Corbitt, 2001). Research has found color to be an important factor in e-commerce,

influencing website aesthetics (Agarwal and Hedge, 2008; Coursaris et al., 2008; Schmidt and Liu, 2005)

e-retailer perceptions (Agarwal and Hedge, 2008), user preference for e-commerce websites (Lee and

Koubek, 2010). Studies are largely associated with the impact of colors on website readability, offering

recommendations about how to choose the most harmonious colors (Hill and Scharff, 1997; Hall and

Hanna, 2003; Nielsen (2000). Yet, color is omnipresent on e-commerce websites. Aware of the

significant and widely known impact of the atmosphere inside stores on consumer activities and behavior

in a traditional buying situation (Kotler, 1973; Donovan and Rossiter, 1982; Filser, 1994, 2003a, 2003b;

Lemoine, 2003), there is a need to investigate the effects of colors as a component of e-commerce

interfaces, on online consumer behavior.

Color has always been used by human beings as an aid to recognize important information among other.

In addition, it can aid an individual’s memory in retaining and recalling information in many activities,

including education or purchases. Similarly, in the online context, the color of an e-commerce website

can possibly improve consumer memorization of information presented in the website.

With the large amount of information presented on e-commerce websites, memorization becomes an

important factor for buying online since consumers are often facilitated in their purchases when they can

retain information from one page to another. This implies that memorization of information in an e-

commerce website may have an impact on consumer buying intention and can potentially be facilitated

by the website colors. However, the relationship between memorization and purchase intention online

has not been investigated. In addition, there is a lack of research regarding color and its effect on

memorization and buying intention in e-commerce websites.

To address this gap, the aim of this paper is to examine how the colors of an e-commerce website can

help consumers memorize information so as to end up buying on the website. The paper presents an

empirical study of the effects of e-commerce website color on the memorization of product information

and buying intention. Our research method includes both a qualitative and a quantitative part. Unlike

most empirical studies dealing with color by comparing warm and cold colors, we examine color by

focusing on its hue, brightness and saturation, following the recommendations of Gorn et al. (2004), so as

to demonstrate that its influence varies according to the intensity of each of these three components. Our

findings show that the colors used on an Internet website have a positive effect on memorization of

product information and buying intention, which is also mediated by mood. They also show that mood

acts as a mediating variable for the effect of colors on memorization.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In the next section a literature review on color and web interface

aspects is provided. The following section presents the research model and hypotheses. The empirical

testing of the model, including the exploratory qualitative study followed by a quantitative study is

described next. The section that follows presents our results which are subsequently discussed in the next

section. The paper ends with the conclusions, implications for theory and practice, limitations and future

research.

3

1BCOLOR AFFECTS MOOD AND ONLINE PURCHASE DECISIONS

Color contains three principal components (Trouvé, 1999):

• The hue (or chromatic tonality), which is the attribute of the visual sense defined according to the

colors denominations such as blue, green, red;

• The saturation, which provides the proportion of chromatically pure color contained into the total

sense;

• The brightness, which corresponds to the component according to which a surface illuminated by a

source seems to emit more or less light.

To this day, the effects of the three color components on the Internet have been but seldom documented.

In the offline environment, Bellizzi and Hite (1992), Dunn (1992), Drugeon-Lichtlé (1996) and Pantin-

Sohier (2004) chose hue as the main variable in their experiments and showed that brightness and

saturation should be taken into consideration when conducting experiments about color. As Valdez and

Mehrabian (1994), Drugeon-Lichtlé (2009), Camgöz et al. (2002) and Gorn et al. (2004) show about the

brightness component of color, an experiment involving color should compare hue and brightness rather

than warm and cold colors in order to understand what consumers recall and what influences their buying

intention.

On a website, the interface represents a graphic chart, which refers to a collection of website elements. A

graphic chart includes two colors, the foreground color and the background color, both of which

constitute the color scheme. These colors reveal the contrast, which corresponds to a strong opposition

between the foreground and the background colors, as defined by W3C (W3C, 2008). Its main function

relies on facilitating the readability of the displayed information, and a fortiori the memorization process.

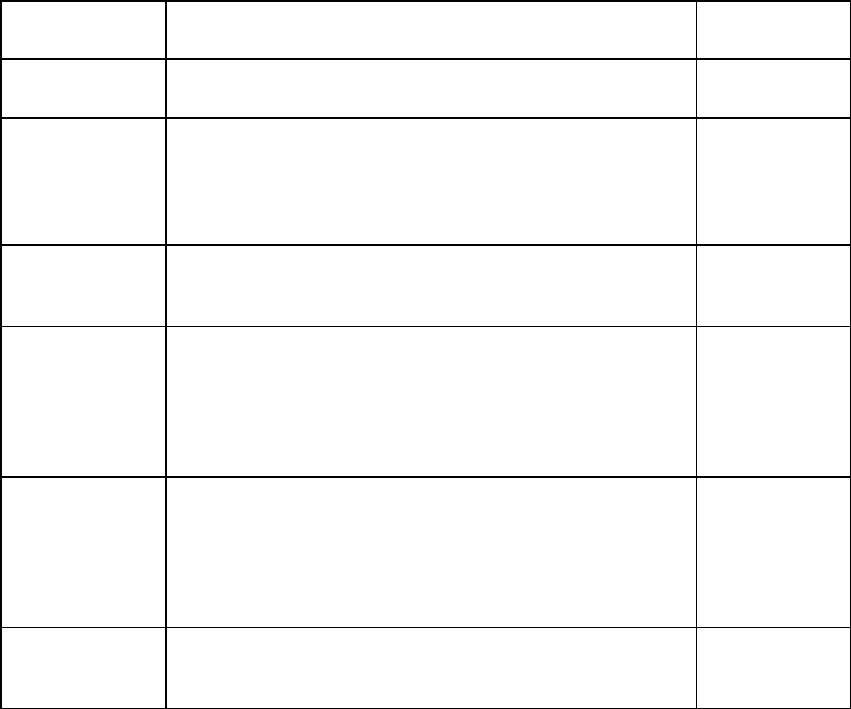

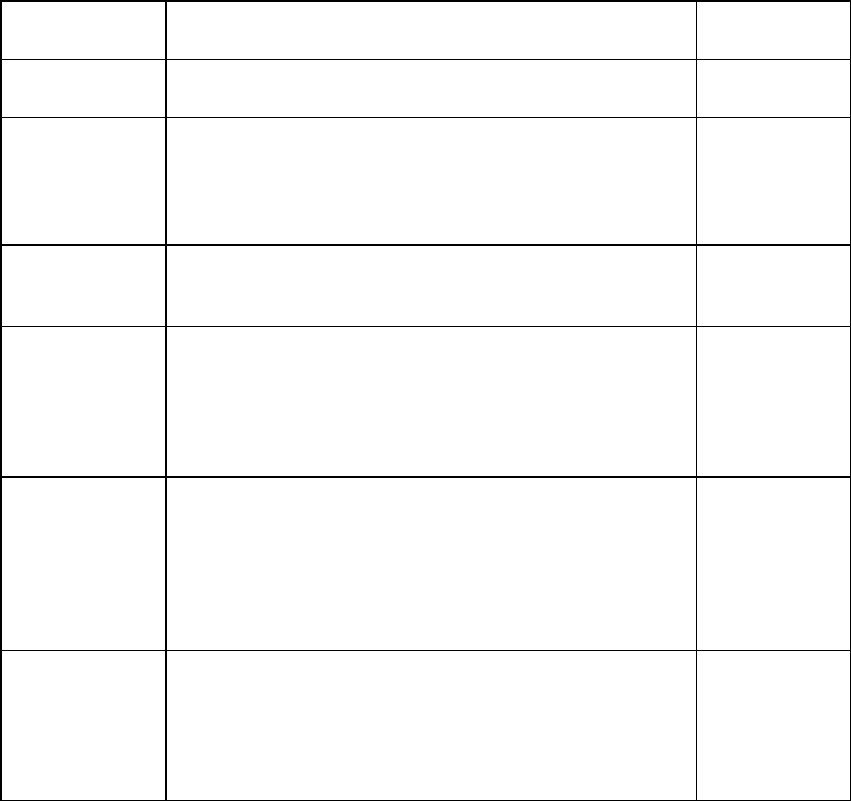

A summary of the main studies on color in a computerized context is presented in Table 1.

4

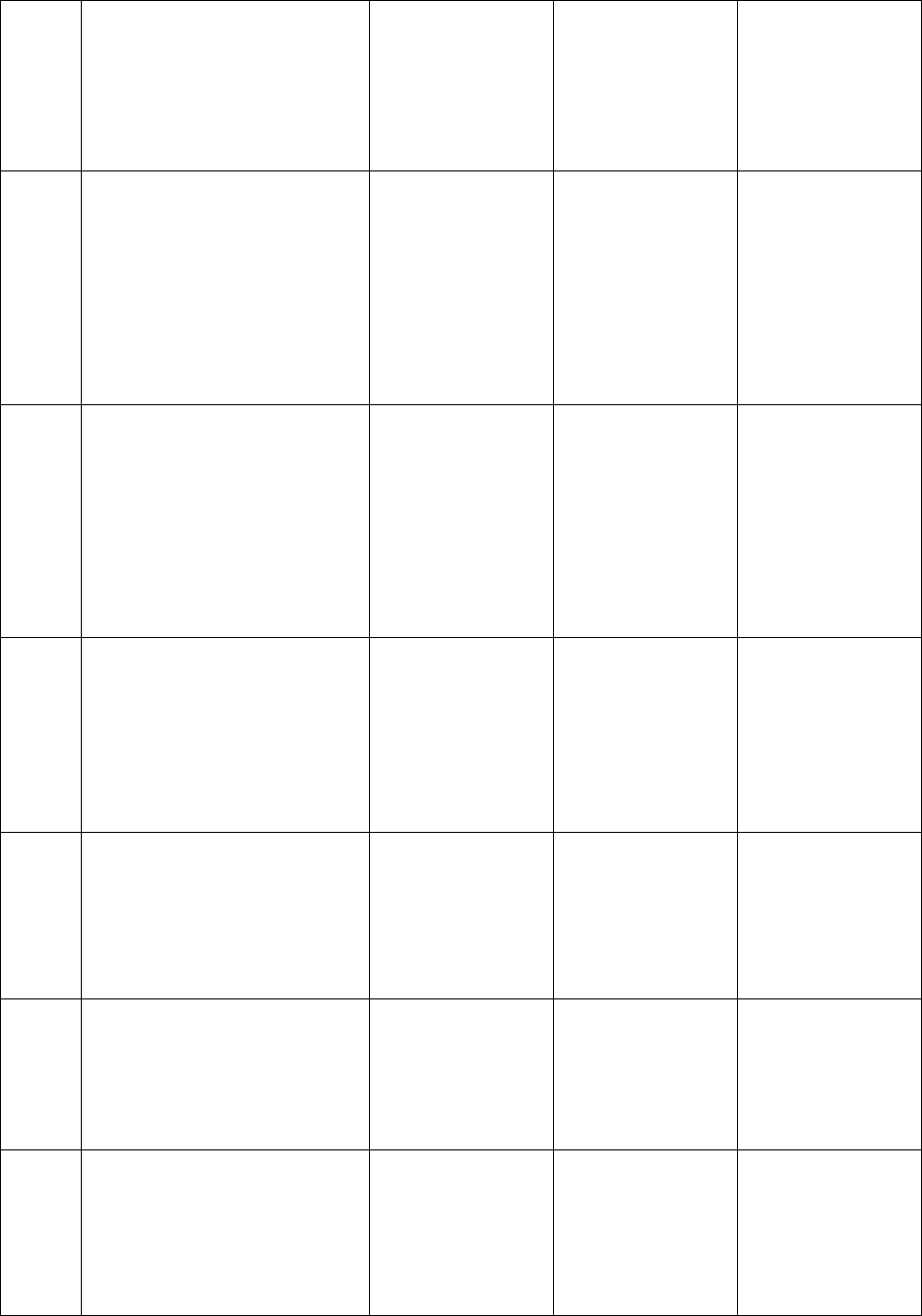

Table 1 : Studies on computer interface color and its effect on other variables

Critique

Color as part of

aesthetic

aspect, not

specific

variable

Cold vs. warm

colors were used

rather than the

components of

colors

The sites were

identical in

content varying

only in color,

balance, or

a

combination of

the two.

Experiment

based on

aesthetics, not

on memorization

or buying

intention

process.

Results

(1) pre-use usability and task

completion time were correlated;

(2) the relationship between pre

-

use

usability and preference was greater

th

an that of task completion time

and preference; (3) design attribute

assessments after actual use were

highly intercorrelated; and (4)

organizational structure and layout

had a greater effect on user

preference than aesthetic aspects,

such as color and typ

ography

More favorable perceptions

regarding a website design’ s

aesthetics when cool color

combinations (blue-

light blue), as

opposed to warm color

combinations (red

-

orange), are

used.

This study focused on the role

aesthetics play in website usability.

Pe

rceived usability was measured

as the design principles of color and

balance were manipulated. No

statistical differences in user

satisfaction between the four sites.

13 among 23 factors showed

differences based on subjects

related to navigation, language

used

and visual content

Experiment

Experiments on nine online

bookstore websites with ten

participants

A 2 x 2 between

-

subject

research design manipulates

the temperature of a

Website’ s primary and

secondary colors.

Viewing screenshots of four

homepages

A

nalysis of 23 factors intended

to compare the results

according to the gender

Scales

Objective performance measures

(task completion time), evaluation

of the design factors, and decisions

of preference on the websites

7

-

point Likert scales (anchored

“Stro

ngly Disagree/Agree” )

measured responses to the question

“My perception of this Website is

that it is…”

for each of the

following items: clean, clear,

symmetric, aesthetic, pleasant for

classical aesthetics, original,

creative, fascinating, sophisticated,

and uses special effects for

expressive aesthetics

A usability checklist was developed

by selecting 36 guidelines for web

design and usability (Koyani

et al.

,

2006)

Interviews

Independent

variable

Color (Aesthetic

aspects)

Color temperature

and gender

Co

lor and balance

Internet sites Color,

Gender

Dependent

variable

User preference

Perceptions of

Website

aesthetics

Perceived

usability

Aesthetics

Reference

Lee and Koubek

(2010)

Coursaris

et al.

,

(2008)

Brady and

Phillips, (2003)

Moss

et al.

,

(2006)

5

C

ritique

The experimentation

does not take the

memorization process

into account

Color combinations

rather than color

components were used

Interesting experience

to prepare the

laboratory conditions

of our experimentation.

No variable related to

the psychological

aspects of the

respondent was

measured.

Work on time, nothing

on memorization of

information and on

buying intention

Results

Moderate or even high color

contrast does not guarantee quick

visual perception. With black and

white information, the spee

d of

visual perception decreases with

decreasing contrast. Visual

search times, number of eye

fixations, and mean fixation

durations increased strongly with

decreasing luminance contrast

despite the presence of color

contrast.

The speed of reading text in

different color combinations

cannot be described as one

-

dimensional problem.

Mathematical metrics were

mostly in contradiction with the

judgment of the observers

Red background infers a

perceived duration longer than a

blue one

Experiment

Eye movements d

uring the visual

search experiment were recorded

simultaneously with threshold

search time measurement by

using an SMI (Sensomotoric

Instruments Inc.)

Testing 56 color combinations

and identifying 21 uppercase

alphabetic characters, selected

and presented

in conformance

with the Snellen chart

Observ

a

tions

;

quantification of treatments of

the digital image color (e.g.

contrast, brightness)

;

-

55 observers making

comparative tests and tests of

absolute measure around various

configurations of 8 colors

Time perception

: Students

placed in front of a program and

to whom questions were asked

concerning the program and the

execution of certain tasks

Scales

Content analysis

ANOVA, t

-

test to study

the differences in legibility

among pairs of color

combinations

None

3 items of speed

Independent

variable

Luminance contrast

Color combination of

a text color and

background color

Colors and colored

appearances of

compared images

following various

compression levels

Foreground and

background color

Dependent

variab

le

Speed of visual

search and reading

Speed of reading

-

Number of correctly

identified characters

as a measure of

legibility

performance

Appearance of

compressed images

Comparative tests

(organized, forced

choice) and absolute

measure tests were

used

Per

ceived download

speed

Reference

Ojanpää and Näsänen,

(2003)

Humar

et al.

, (2008)

Fernandez

-

Maloigne,

(2004)

Gorn et al.

, (2004)

6

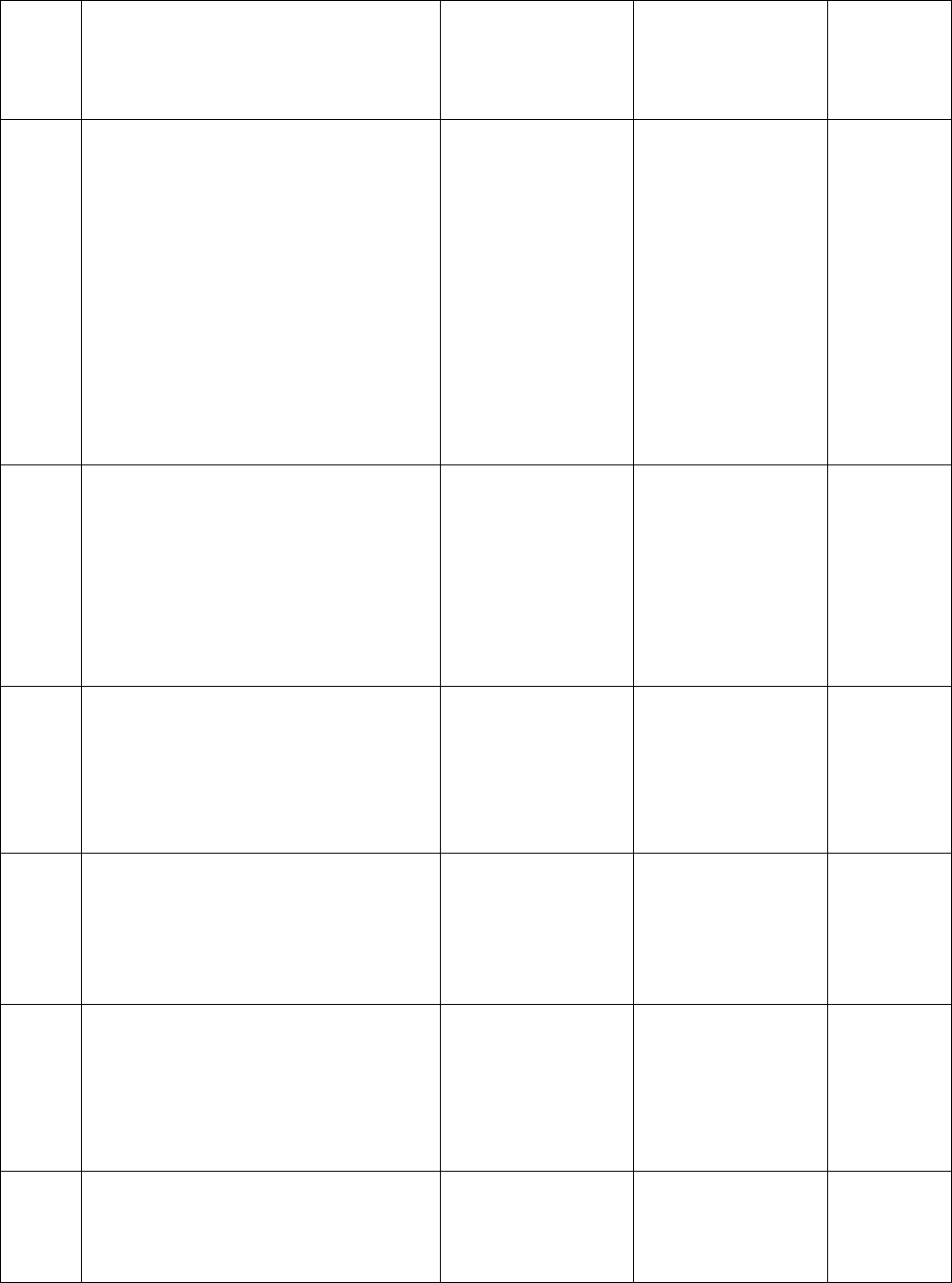

Critique

Cold vs. warm

colors were

used rather

than the

components of

colors

Nothing about

the buying

intention

variable

Co

ld vs. warm

colors were

used rather

than the

components of

colors

Only a few

colors were

used for this

experiment, it

is not easily

generalizable.

Results

Music and color factors had a significant effect on

participants’ emotional response Participants fe

lt

more aroused and experienced greater pleasure

when they were exposed to a warm color website.

Absence of significant effect of peripheral color and

its constituents

It seems to be preferable to use more than four

colors or monochromatic and analogical

It seems to be preferable to use low contrast levels

between colors

Cold colors are perceived as more suitable than

warm ones

For monochromatic color scheme, it is preferable

to have high contrast in brightness

Regarding saturation, it was found that the b

est

combination is high saturated background color

with low saturated secondary color.

1) Time passes more slowly with white, blue,

green backgrounds

2) No effect on color on time pass

A white background allows easier reading but a

slower search and more d

ifficult co

m

prehension

Experiment

Laboratory experiment with a 2

(music: fast/slow) x 2 (color:

warm/cool) between-

subjects

factorial design

-

Self

-estimation of the duration

of their own test;

-

Study of various personality

traits in interaction with com

plex

mental processes such as

attention capture, reading,

semantic memorization

A machine learning algorithm

generates a network that relates

the color model of a website

with the emotional values that

are attributed to it by its users

1) Effect of 5 backg

round

colors (white, red, green, blue,

yellow) on 50 subjects who had

to search for information in a

directory

2) Search and

understanding

Scales

12

-

item semantic

differential scale

(Mehrabian and

Russell’ s, 1974)

modified for online

shopping to measure

participants’

emotional response to

the surroundings in

terms with a 7

-

point

Likert scale, Arousal

dimension: happy

–

unhappy, pleased–

annoyed, satisfied

–

unsatisfied,

contented

–

melancholic, hopeful

–

despairing, and relax

–

bored.

-

SSS version V of

Zuckerman

(1994)

(opt

i

mal level of

stimulation)

-

Locus of control

(LOC) (Rotter, 1966)

-

Androgynous of Bem

(BSRI) (Bem, 1974)

-

Confidence level (9

-

point Likert scale)

Bayesian Belief

Network (BBN)

Time error, Response

time, Devotion,

Interest, Irritation,

Fatigu

e, Achievement,

Difficulty

Independent

variable

Website music and

color

Website colors

Color

characteristics

Website colors

Dependent

variable

Emotional responses

and subsequent

shopping behavior

-

Sense

-

motivation

-

Mouse manipulation

-

Cognitive

:

memorization

-

Explanatory

: sex,

initial mood, opt

i

mal

level of stimulation

Affective state (12

most emotional

descriptors: Pleasant,

Formal, Fresh,

Modern, Friendly,

Aggressive,

Professional,

Attractive, Calming,

Dynamic, Reliable and

Sophisticated)

Tim

e spent on a

website

Time spent for

searching information

Understanding

of

found information

Reference

Wu

et al.

,

(2008)

Roullet, (2004)

Papachristos,

et al.

,

(2005)

Kiritani and

Sh

i

rai, (2003)

7

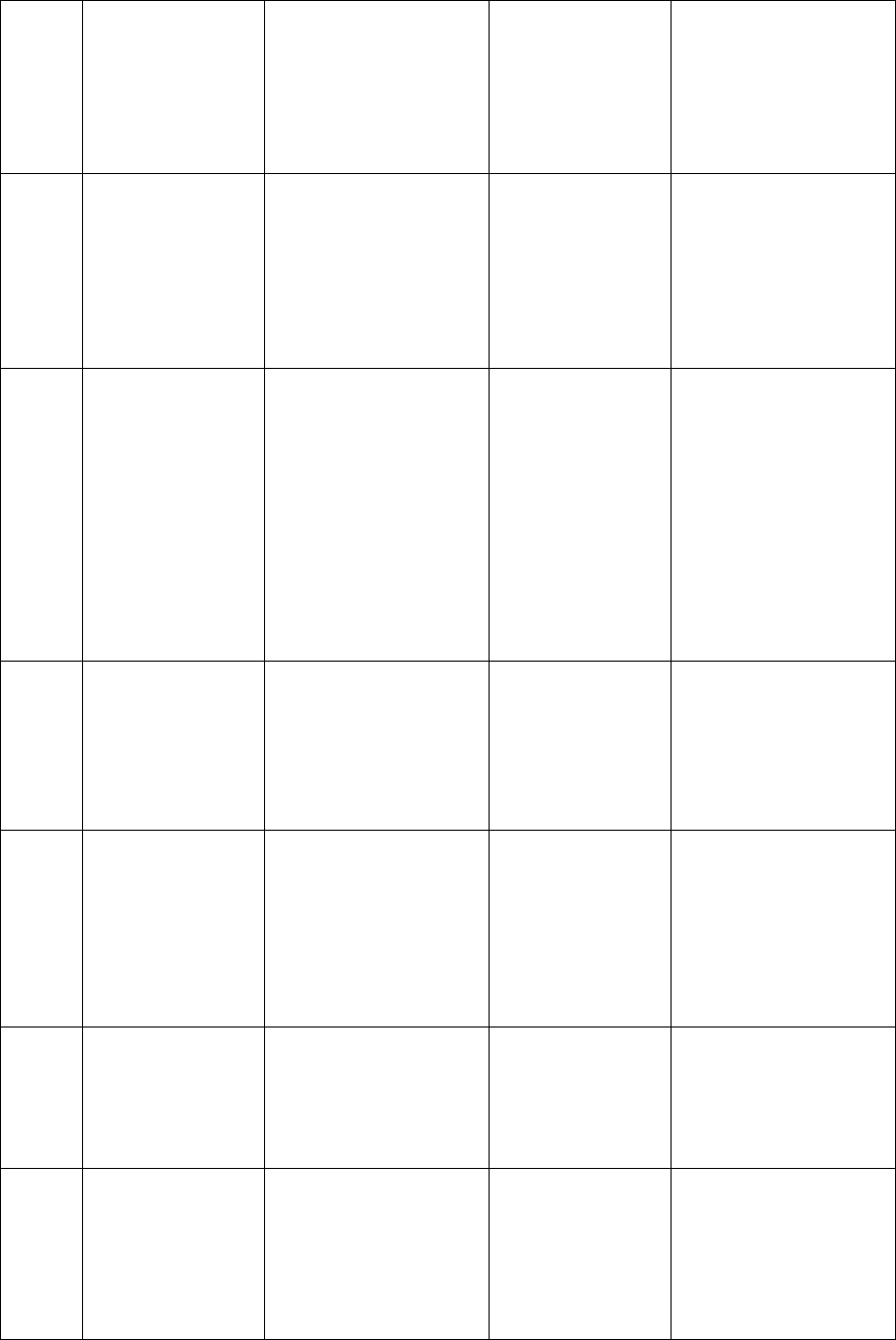

Critique

No measure of

memorization

Testability of a colo

r

vision screening test in

a population with

mental retardation, no

measure of

memorization

Discriminating abi

l

ity

measures for predicting

rea

d

ability of text on

textured backgrounds,

no measure of

memorization

Testing the rea

d

ability

of web page colors, n

o

measure of

memorization

Results

Both experiments showed

significant main effects for

all variables, and that all

interactions were

significant

.

The overall rate of

testability was 93.2% for

the 1078 athletes screened.

The frequency of males

identified a

s color

deficient was similar to

that expected in the

general population; only

two females (in Spain)

failed the color vision

screening.

Search times indicate that

these background

variations only affect

readability when the text

contrast is low, and that

spatial frequency content

of the background affects

readability.

Readability increases as

the difference of clarity

between the text color and

the background color

increases.

Regardless of the direction

of this difference, clarity is

an important factor f

or

determining the readability

of a text on a colored

background

Experiment

Experiment I: Measuring the effects of

transparent text:

It employed a 2 (text

transparency type) x 2 (text contrast) x 3

(background) within participants design

Experiment II: Measuring the effects of

very low contrast one color combination

(gray on gray) and one

background luminance level

Readability / Mentally handicapped

persons

Readability / Screen background with

texture

149 subjects and 42 samples

Images having different te

xt colors on

different background colors. It was

necessary to note the readability of

images.

Images in GIF format (modification of

text impossi

ble) using the 216 safe colors.

Scales

Text Contrast, Adjusted

Text, Contrast,

Background, RMS

Contrast, Adjus

ted

RMS, Contrast, Global

Masking, Index,

Adjusted Index

Testability of the

"Color Vision Testing

Made Easy" color

vision test and with a

test using simple

geometric figures that

are easily identified

Several

discriminability

measures were

examined (plain,

a

periodic texture, and

four spatial

-

frequency

filtered textures

created from the

periodic texture).

Scale ranging from

“impossible to read”

to “ readable without

effort

» presents on

screen

Independent

variable

Text color with different

modes

-

Transpa

rent

-

Opaque

-

Weak contrast (with

screen background)

Colors

Text color and screen

background color

Text color and image

background color

Dependent

variable

Text readability

Effects of color

readability on

subjects with

mental

deficiencies

Text readab

ility

Readability of

images containing

text

Reference

Scharff and Ahumada,

(2002)

Erickson and Block,

(1999)

Scharff and Hill,

(2000)

Ridpath

et al.

, (2000)

8

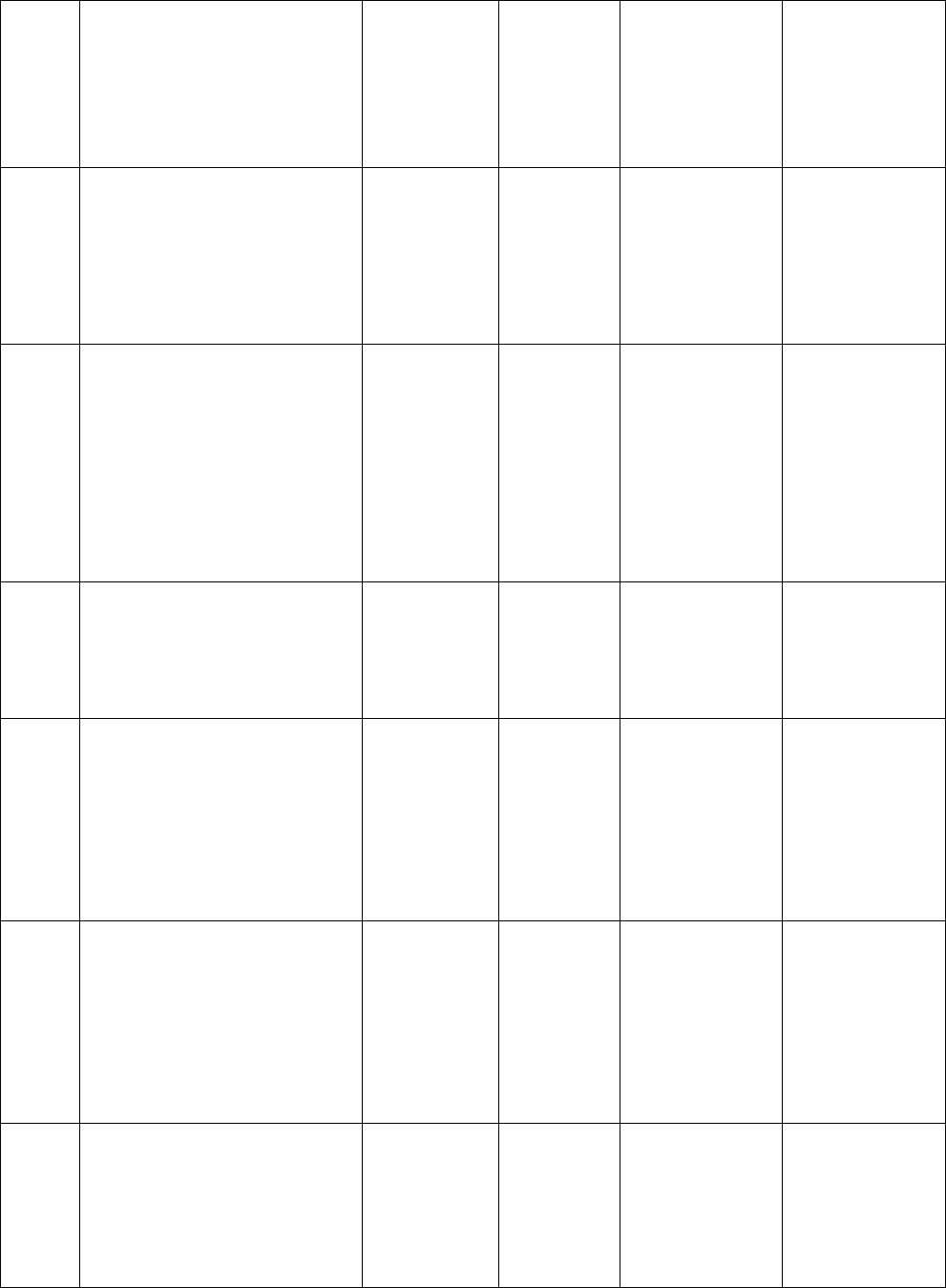

Critique

Readability of websites

with various

for

e

ground/back-

ground color

combin

a

tions, no

memo

rization process

measured.

Background color only

Comparison based on

chromatic vs. a

-

chromatic colors only

Color and pattern were

measured rather than

colors only

Comparison of graphic

charts with no

modification of the

levels of brightness

and saturation.

Results

In general these results

suggest that there is no

one

foreground/background

combination, font, or

word style which leads

to the fastest RT (i.e.

best readability), but

rather a designer must

consider how each

variable affects the

other(s).

Subtle

design

manipulations had

significant effects on

consumer evaluations of

web page aesthetics and

perceptions of the e

-

retailer

Women tend to use

color in their histogram

choice more than men

and color seems less

important for men

Subjects mention in

advanc

e the attractive

products, the picture of

which kept their

attention more than the

rest

Elimination of different

quite incoherent types of

memorization (retention

due to aesthetics and not

always to contrast)

Experiment

The effects of 6

foreground/backgro

und color

combinations (color), 3 font types

(Arial, Courier New,

& Times

New Roman), and 2 word styles

(Italicized & Plain) on readability

of websites were investigated.

Participants (N=42) scanned

simulated websites for a target

word; readability was inf

erred

from reaction time (RT).

Conjoint analysis and optimal

design methodologies sixteen web

page prototypes assessed through

an online survey

93 subjects have to measure the

complexity of color and black &

white histogram information

385 subjects have to allocate 100

points according to their

preferences; A

d

ministration of

online questionnaire

Readability test of 136 partic

i

pants

of 2 web pages with chromatic

manip

u

lation

-

multiple choice questionnaire

Scales

Readability / Text

color and screen

background color

Background

color, white

space, thumbnail

image location

and thumbnail

image size were

varied

Likert scale

indicating their

confidence in

their choice

7

-

point Likert

scale on the

importance of

security and price

10

-

point Likert

scales

Independe

nt

variable

Foreground and background

colors

Background color

Graphics color

(histograms)

Appearance / choice

according to the color of the

screen background of

attractive products (or not?)

Car

: 1) orange red & 2)

green with dollars.

Sofa

: 1) blue w

ith clouds &

2) green with cents

-

Black text /White

background

-

White text /Black

background

-

Light blue text /Dark Black

background

-

Tu

r

quoise text/Black

background

Dependent

variable

Reading speed on screen

Aesthetic evaluation and

perception of e

-

retailer

consumer trust product

preference and purchase

intention

Decision performance and

accuracy

Gender, decision

-

making,

task analysis

Purchase intention

Reading speed

Information memorization

after reading

Reference

Hill and Scharff,

(1997)

Agar

wal and Hedge,

(2008)

So and Smith, (2002)

Mandel and Johnson,

(2002)

Hall and Hanna,

(2003)

9

Gorn et al., (2004) focusing on the impact of the three color components on downloading time perception

demonstrate that a lengthy waiting time influences the user’s appraisal of the Internet site and can lessen

his/her desire to recommend it to others. Kiritani and Shirai (2003) show that the effects of screen

background colors on time perception vary according to the tasks performed by Internet users. When

reading a text written on a white, blue or green screen background, users have the feeling that time passes

more slowly. When users merely conduct a simple search and only need to understand the meaning of a

sentence, then the screen background color does not have any impact on how they perceive time duration.

Hill and Scharff (1997) have demonstrated the importance of contrast (foreground color vs. background

color) when searching for information within a page. They obtained better readability scores when

resorting to chromatic colors (green foreground color on yellow background color). During an

experiment where colored labels had been placed on screen backgrounds, Camgöz et al. (2002) observed

that brightness, saturation and hue had a specific impact on each colored screen background.

Biers and Richards (2002) have studied the impact of background color on the perception of promoted

products and found that backgrounds with cold hues, such as blue, increased product value and reduced

the risk of purchase postponement, especially with regards to regular Internet users. Hall and Hanna

(2003) studied the impact of background and foreground colors on how readability was perceived and

aesthetic aspect experienced, as well as on the retention of information and on intentions. According to

them, sites promoting knowledge transfer must display black texts on white backgrounds, achromatic

colors with maximum contrast. In addition, they indicate that e-commerce websites should merely use

chromatic colors due to the higher aesthetic appreciation score which is correlated to higher purchase

intention. Blue is the favorite hue for purchase intention. These results underline that when studying

color on a website, it is important to take into consideration color components (hue, brightness and

saturation), as well as the contrasts of the foreground and background colors.

A number of studies have shown that color has a positive effect on consumer mood (Wu et al., 2008) and

buying intention (Wu et al., 2008 ; Roullet, 2004). However, color has mainly been addressed in terms of

warm and cold hues (Coursaris et al., 2008; Papachristos et al., 2005) and has not examined with respect

to its components, hue, brightness and saturation. Most of the studies linking color and e-commerce take

into account balance or brightness as variables of colors (Brady and Phillips, 2003) or combinations of

colors (Humar et al., 2008), which do not allow for comparing the effects of the components of the

colors. Memorization doesn’t seem to be recognized as an important variable in e-commerce considering

the poor amount of research on this topic. For example, Hamilton and Luo (1999) have shown that the

degree of complexity of an e-commerce website varied according to the colors of the interface which

helped the consumer to be concentrated. However, many studies on the effects of color on readability

exist (Hill and Scharff, 1997, 1999; Hall and Hanna, 2003). In addition, research has not studied how

memorization affects buying intention.

2BRESEARCH MODEL

The proposed model follows the general pattern of consumer behavior. It follows the one from Engel et

al. (1978) and introduces three innovative contributions in the consumer behavior analysis (Filser, 1994).

It analyzes the variables that influence the consumer's decision process by distinguishing three

categories:

• Characteristics of the individual;

• Characteristics of its social environment;

• Situational factors.

This model offers precision about the different stages of the perception of stimuli process, which

comprise exposure, attention, understanding, acceptance and retention. It suggests measures of these

different levels of perception. It finally breaks down the decision process into a sequence of five steps.

The latter are commonly used in research on consumer behavior. The model explains how the colors of

an e-commerce website and specifically their components - hue, brightness and saturation - can have an

10

impact on the buyer’s affective state of mood and cognitive states of memorization and buying intention

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Research model

9BMemorization

Memorization is a very important factor for the large number of information-based websites that

currently exist. It is important for e-learning applications, since the user goal is usually to retain the

information beyond the time the page is being read. This also applies to information included in e-

commerce websites, since consumer tasks are often facilitated by memorizing information while

navigating. Drawing on offline settings, we argue that memorization can be influenced by the colors of

an e-commerce website.

In order to understand the effects of color on consumer memorization we have to take into account the

quality and quantity of information a consumer has memorized while visiting an e-commerce website.

We posit that memorization varies according to the colors of the website, and especially according to the

contrast between background and text colors, in agreement with the work of Hall and Hanna (2003). As

we stated earlier, the aim of this research is to investigate the effects of the components of colors rather

than colors themselves.

In general, information is stored according to an encoding process enabling one to sort out information

thanks to criteria which will then allow one to retrieve this information. The role of these criteria is to

connect a piece of information to other similar information already stored (Ladwein, 1999). In order to

examine the information memorized by each participant, we resort to recognition and recall, two

procedures belonging to a method of information retrieval based on overall stimulus in long-term

memory. Be it free or cued, recall enables individuals to mimic mentally a stimulus to which they are not

exposed during the evocation, for instance, their past reaction to a promotional action (Filser, 1994).

Thus, we can hypothesize:

H1: The components (hue, brightness, saturation) of colors of an e-commerce website will have a

positive effect on memorization

10BBuying intention

Intention is activated by a desire or a need (Darpy, 1997) and desire is viewed as an active process

(O'Shaughnessy, 1992). Although buying intention is more than a mere desire, it is not a promise to buy

(O'Shaughnessy, 1992), it is the outcome of a cognitively handled desire. According to Darpy (1997),

11

building on the studies of O'Shaughnessy (1992), Howard (1994) and Belk (1985), “Intention is the result

of a desire or a need handled on the cognitive level and leading to purchase planning”.

Among the environmental factors recognized to produce important emotional and behavioral reactions on

the consumer, color seems to play an important role. It serves to retain consumers longer on the e-

commerce website according to certain criteria related to their perception of the interface. In particular,

pleasure is increased with use of colors whereas boredom can result from a weak use of them (Lemoine,

2008). This duration can help maintaining user interest in a site (Bucklin and Sismeiro, 2003, Hanson,

2000) and give users more time to consider and complete purchase transactions (Bucklin and Sismeiro,

2003). By enhancing consumer interest, it helps to generate repeat visits, which lead to greater long-term

sales (Moe and Fader, 2004). From a business investment point of view, Demers and Lev (2001) show

that sites with longer visit duration also have higher monthly stock returns. Therefore, it can be assumed

that e-commerce website colors are likely to have an impact on buying intention, as they can prolong the

visit duration. According to Agarwal and Hedge (2008), the background color of e-commerce web pages

is an important factor affecting purchase intention. Wu et al., (2008) have found that warm colors of e-

commerce websites have a positive effect on purchase intention. As already mentioned, we are interested

in the effect of color components, hue, brightness and saturation. Therefore, we propose:

H2: The components (hue, brightness, saturation) of color of an e-commerce website will have a positive

effect on consumer buying intention

There are many entries which are available in the memory and in the external environment. They can

potentially be considered in the decision task, but only a few will be used to make a choice in a given

situation. Tactical choices effectively originate from decision making regarding the products we buy,

including:

• Considerations linked to the price (cheaper, use less of it, cost a cheaper price);

• Considerations linked to the performance (the product functions in these conditions, it owns

these qualities);

• Considerations linked to the affect (I like the product, I love the product);

• Normative considerations (my father advised me to buy it, my mother always uses this product);

It is important to understand the procedures which determine which part from memorized information

can be used for making a choice. For these reason, we propose:

H3: Memorization will have a positive effect on consumer buying intention

11BMood, a mediating variable

We wish to bring to the fore the effects of colors on affect, which includes mood experienced when

visiting the e-commerce website. Mood refers to affective states of mind less likely to reach our

conscience. Moreover they last longer than emotions but are less intense (Forgeas, 1999).

Mood is linked to a color perceived as positive or negative according to the personal experience of an

individual with a color (Boyatzis and Varghese, 1993). According to Odom and Sholtz (2004), different

colors tend to incur different moods. Studies have demonstrated the association of colors and mood by

using diverse methods such as the objective impressions (printings), the clinical observations, the

introspection and the experimental investigations (Wexner, 1954). Chebat and Morrin (2006) measured

the effects of cold vs. warm colors of a mall decoration on consumer perceptions. They showed that these

were mostly driven by affective mechanisms such as mood, or by other cognitive states, such as the

evaluation of the mall environment quality. Similar mechanisms can exist in an online context. Wu et al.

(2008) have found that e-commerce website color has an important effect on consumer mood. However,

their study focuses on warm and cold hues of website color and their influence on mood and does not

examine the hue, brightness and saturation color components. In this study, we investigate the direct and

interaction effects of the components of colors. Hence, we suggest the following hypotheses:

12

H4: The components (hue, brightness, saturation) of color of an e-commerce website will have a positive

effect on consumer mood

Mood is generally considered as a mild affective state that may influence cognitive processes such as

evaluation, memory and decision strategies (Gardner, 1985). However, the observed effects of negative

moods have been less consistent than those of positive moods. For example, Cialdini et al.’s (1973)

negative state relief model of helping asserts that people in a negative mood will behave more charitably

than others if the opportunity has potential for direct social or egoistic approval, suggesting that helping

behavior may be quite a complex phenomenon not fully addressed by simpler explanations such as mood

states (Swinyard, 1993). Gardner (1985) observed that the effects of mood may have special impact in

retail or service encounters because of their interpersonal or dyadic nature, a view also supported by

others (Isen et al., 1978; Westbrook, 1980).

H5: Consumer mood will have a positive effect on memorization

When people are in a good mood, they tend to have more favorable expectations for the future (Eysenck,

1976; Masters and Wyndol, 1976). Drawing on research in offline stores, good mood may contribute to

consumers intention to return to a website at which they have made previous purchases (Isen et al.,

1978). We expect mood to be important in the context of online purchase since many consumers make

purchases after having a pleasant time visiting a website. This is in line with the study of Wu et al. (2008)

suggesting mood as a significant predictor of purchase intention. Thus we propose:

H6: Consumer mood will have a positive effect on buying intention

3BRESEARCH METHOD

Our research method includes both a qualitative and a quantitative study. An exploratory qualitative

study was conducted first to allow for verifying the importance of the research variables and the necessity

of including them in our model to be tested. The proposed research hypotheses were then empirically

tested through a quantitative study conducted in a laboratory setting.

Qualitative study

The main objective of the exploratory phase was to investigate the empirical knowledge gained by

regular consumers and expert users when browsing e-commerce websites. It mainly sought to confirm

that colors have an impact on users’ perceptions, so as to prepare our quantitative study for data

collection. In this direction, the study explored long-term memory and the website factors that influence

it, drawing from Eroglu et al., (2003) suggesting that atmospheric cues affect consumer behaviour. The

study was based on semi-structured interviews conducted with regular consumers and web designers,

where we asked interviewees to speak about past visits to websites of their choice. The interview guide

and the specific research objectives of the questions are shown in Table 2. From these interviews, topics

referring to the affective states lived by the consumer in an online shopping situation emerged. These

topics relate to the emotions and moods and show the importance attached by the consumers to the ease-

of–use of a website. They also reinforce the proposed effects of variables such as color, as well as the

quality of the images perceived by the consumers.

Table 2: Interview guide questions used for data collection and relationship to research objectives

Question

Research objective

1. Phase of introduction: use of Internet in general:

a. Could you speak to me about your use of Internet?

b. Do you often use the Internet for shopping?

Learning about the consumption and

familiarity’s experience of the consumer.

2. Phase of centering the subject:

Investigation into the long term memory in

13

a. Now I would like you to remember your last visits to e-

commerce websites to carry out activities for shopping on

the Internet. By e-commerce websites, I understand the sites

which offer products like books, CDs of music, DVDs, cars,

travels, hotels, flights and train booking tickets, banking

services, etc. Can you remember your visit to a particular

website to seek information on a product or to buy this

product?

b. What do you think of this site in general ?

order to learn what is remembered by

consumers after their visit to an e-commerce

website.

The consumer’s thinking is also interesting to

assess since we want to understand what is

related with what is memorized.

3. Phase of deepening

Topic 1: atmospheric elements of the commercial sites

a. What do you think of the design of this website?

b. What represents a commercial website which you have

found rich, captivating and pleasant to visit?

Topic 2: Emotions and feelings felt following the

consultation of a commercial site

a. Could you describe the feelings that you associate with an e-

commerce website?

b. user called his friend:

“It sometimes happens, that while surfing on an e-commerce

website, the site holds my attention because it is beautiful,

and easy to surf and to consult. It enables me to go quickly

because I easily find the links which are of interest to me and

I never feel lost when I use it. Links are easy to locate and

help me when I am lost. The facility of reading the site gives

me desire to spend even more time on it: the links are quite

visible, the images are very clean, and I can perfectly

distinguish such and such part of the page of a site, because

the colors are used in an intelligent way, to delimit the

parts”.

c. (To be read again several times if necessary)

Your opinion?

a. Do you think you have already experienced these states?

b. If so, could you speak to me about an experience of this kind

by describing an e-commerce website for example?

c. According to you, why did you live these states?

Topic 3: Antecedents of the behavioral approach

a. What encourages you to buy on a particular website and not

another?

b. According to you what makes you spend more time on one

website than on another?

c. In your opinion what makes you switch to an e-commerce

website?

d. What are the factors which encourage you or discourage you

from revisiting a particular website?

The aspects in terms of design counts in the

consumer’s appreciation. But at which level ?

Qualitative adjectives (rich, captivating…) can

enhance the consumer’s description of a

commercial website, as a way to help him.

The vocabulary dedicated to feelings

contributes to feed our understanding of

aspects linked to the perception.

The projective technique is helpful since

consumers do not have to invent anything.

They can try to remember a past navigation,

which seemed close to a perfect one in order to

compare it with a normal navigation on an e-

commerce website.

The interview is then based on the

interviewee’s perception after he has visited

such a website. He is asked to describe this

period in order to relate particular lived states.

The reason why he experienced these states is

then questioned with the objective to elicit

sentences dedicated to emotional states.

The question we asked in order to understand

behavior when facing an e-commerce website

targets the consumer’s loyalty. Questions were

thus oriented towards the ease of use and ease

of surfing the website as well as questions

linked to ergonomic and interest to the website

aspects.

Phase of conclusion

What makes you say, after having visited an e-commerce

website: “I have visited a really good website which inspires

me to buy from it and to explore it more”?

Can you think of any ideal e-commerce website?

During the conclusion phase, we tried to get

ideas related to the best conditions participants

would like to have experience when shopping

on the Internet.

An emphasis on an ideal shopping experience

on the Internet was then explored.

Participants

Participants were online shoppers with different levels of expertise in terms of Internet use. Sample

selection was primarily based on qualitative criteria. Since the qualitative study aimed at exploring online

14

consumer perceptions from e-commerce websites, our sample had to have previous experience with

online shopping. In order to qualify for participation in the study, a respondent would have to reply

positively to the question “Have you ever bought a product or service from an e-commerce website?”.

Twenty one subjects, 10 females and 11 males were interviewed. Participants were grouped according to

their expertise with e-commerce websites into expert users and regular users. A participant was selected

as an expert user or not based on the answer to the question “Are you a professional web designer?”.

Subjects characterised as expert users represented 29% of the sample, whereas most of them were regular

Internet users. Finally, the sample was selected pursuing balance in terms of age and socio-professional

background. The sample characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Characteristics of the sample of respondents

Demographic

characteristics

Category

Number of

respondents

Gender

Female

Male

10

11

Age

Under 25 years old

25 - 34 years old

35 - 44 years old

45 - 54 years old

55 - 64 years old

1

13

4

1

2

Internet

familiarity

Expert

Intermediate

Beginner

6

7

8

Education level

Certificate

High school

2nd-year university diploma

License / Master I /Master II

Postgraduate / doctorate / post-graduate / Master degree

no diploma

4

4

4

7

2

Profession

Executives and academics

Intermediate occupations

Manuel Workers

Students

Storekeepers and business managers

Pensioners

2

3

6

4

4

2

Income per

month

From 1000 to 1399 euros

From 1400 to 1799 euros

From 1800 to 2199 euros

9

8

4

Method

The interview guide was structured and open, allowing us to collect data on topics related to the

respondents long-term memory and purchase experience in e-commerce websites (Table 2). Satisfying

the criterion of saturation of the data (Mucchielli, 1991, p. 114), we interviewed 21 persons, with the aim

to collect information from both regular and expert users. We adopted a neutral attitude with regard to

them so as not to influence them in the way they answered. Participants were interviewed without being

able to face a computer screen. This was to ensure that they answer only by using their memory to restore

the information evocating their navigation on the e-commerce website of their choice. Every interview,

the duration of which ranged from 13 to 47 minutes, was re-transcribed offering a verbatim of hundreds

of pages.

15

Results

The exploratory qualitative analysis enabled us to note that color was actually an integral part of the

atmosphere on e-commerce websites. Other atmospheric variables such as fonts, animations, images or

image quality were also revealed during the analysis. However, the interviews show that color seems to

be the most important one. Color was mentioned around 100 times during the interviews carried out.

Table 4 presents a summary of the themes, constructs and modes evoked in the exploratory qualitative

analysis. Given the exploratory nature of our research, the indicated percentages are not intended to be

statistical representative but they rather serve to summarize the information collected in numbers.

Table 4: Summary of the exploratory qualitative analysis

Principal themes

Constructs

Modes

Evoked themes

Citation

frequency

among the 21

respondents

Atmospheric

elements of e-

commerce websites

Colors

Organized in zones

Calm (part clarity)

Not showing aggression

Make the visit more pleasant

Simplify website use (clear organization)

Create an impression of sobriety and reassure

9/21

42,9%

-

-

Lively, sharp

(saturated)

Make the Internet user get tired and lost

Do not facilitate in locating border lines

Create an impression of violence

Make lose trust

6/21

28,6%

-

-

Bright (fluorescent)

Showing aggression

Depreciate the website, (impression of

promotion)

4/21

19%

-

-

Natural (photos of

environment, of

products)

Create a sensation more quickly

Move closer to the product if the size of the

photo is large

14/21

66,7%

-

-

Warm (feeling

creation power)

Stimulate (excite)

13/21

61,9%

-

-

Cold (feeling

creation power)

Sedative effect

Impression of purified website

6/21

28,6%

-

-

Plentiful

Discount image

Incite the user to move in the website

6/21

28,6%

-

-

Sobriety, elegance

Inspire trust

8/21

38,1%

-

-

Harmonious

Emphasize the content, aerate and structure it

7/21

33,3%

Mood

Sadness

Appearance

Download time of interface elements is too

long

2/21

9,5%

-

Serenity

Ergonomic design

Less stress in comparison to purchases made in

a traditional store

14/21

66,7%

-

Nervousness

Colors

Violence of colors

Blink of animations or links

Difficulty in locating links

5/21

23,8%

-

Frustration

Appearance and

information

Unsuccessful search

5/21

23,8%

Beyond an element of the design of the website interface, color seems to comfort the consumer when it is

soft and creates a feeling of assurance necessary for the act of purchase, in an environment to be ‘tamed’.

It supports the organization of information by highlighting useful zones systematically sought by the

interviewed Internet users. When used in compliance with the contrasts, as conceived by Itten (1970),

color can prove very timesaving, a major aspect in the relationship between consumers and websites.

16

With information search made easier by implementing ergonomics and human computer interaction

rules, the colors encountered when browsing an e-commerce website enable Internet users to navigate it

more easily, according to its layout.

Color scheme seems to be important for online consumers, affecting memorization and buying intention.

Apparently information is more easily memorizable thanks to an appropriate color scheme.

Readability built on a good contrast between the foreground and background colors helps consumers

retain information more easily. Readability also facilitated consumers understand the interface and the

online shopping interaction more easily. This made them feel more comfortable with the e-commerce

website, enhancing their intention to purchase.

The conducted interviews also revealed that the ambience of the room where the respondents made their

shopping was important. Some of them argued that shopping online while being at the office in a bright

atmosphere was completely different from spending time on an e-commerce website, with a bed light,

making the atmosphere sober and dark. The perception of the colors of a website can vary depending on

the light of the room where the customer is physically present and the online shopping experience takes

place.

Quantitative study

The results of the qualitative study have influenced the quantitative study that followed, both in terms of

the research hypotheses as well as in terms of the design of the experiment. The importance of color and

its effect on mood, memorization and buying intention implied by the results of the qualitative study led

us to further examine color, mood, memorization and buying intention as variables in the proposed

research model. We thus developed the research hypotheses proposing links among these four variables,

guided by the results of the qualitative study. The research hypotheses were then empirically tested with

a quantitative study in a laboratory experiment. Since the light of the room was found to be important for

consumers when shopping online, it had to be considered for the empirical study. Therefore, a laboratory

experiment was necessary to allow for controlling the ambient lighting of the physical setting. The results

of the qualitative study also reinforced the importance to take into account the environment of the e-

commerce website where consumers spend time shopping, particularly the color scheme. A website

would thus have to be designed especially for the experiment, enabling control of the color scheme.

Respondents referred to tangible goods, therefore, the development and use of an e-commerce website

selling CDs seemed appropriate, similar to the type of e-commerce website they usually visit.

Thus, a laboratory experiment was conducted with 440 participants in order to test the proposed

hypotheses. An e-commerce website selling music CDs was especially designed for the experiment. A

respondent would visit the website and browse the available CDs which were grouped into categories.

There were 57 CDs available in 19 categories (3 CDs/category). For each CD, participants could see the

CD cover, the album title, the artist name, and seven information items, i.e. music category, online store

price, music company price, sale percentage, delivery time, state (new or used) and delivery charge. This

detailed information was displayed by clicking on the cover image or the title of a CD. In addition, the

detailed information included a CD description of 160 characters (around 20 words), next to the CD

cover.

Participants could select a category on the left side of the webpage and see the 3 CDs of this category on

the right side of the same webpage. Participants had to look into the details of a minimum of two CDs of

their choice, regardless of the category a CD belonged to. Participants could look at more than two CDs

if they wanted to, from any category and add them to their shopping cart but they could not conduct real

purchases.

Each participant visited the website with a color scheme which was randomly selected among the eight

schemes prepared for the experiment, explained in the next section. A balanced distribution of the color

schemes among all respondents was ensured. After viewing at least two CDs, an easy to see link

appeared and respondents were asked to complete a questionnaire with questions about memorized

information, mood state and buying intention. Participants were not able to proceed to the questionnaire

unless they had visited at least two CDs, in order to ensure that they had viewed adequate information for

17

responding to the subsequent questions. Demographic data were also collected. All subjects were then

tested for color blindness in a separate room using the highly reliable Ishihara test (Lanthony, 2005). This

guaranteed the validity of our sample’s responses, by keeping people with a perfect vision of colors. The

Ishihara test is the most common color blindness test used today (Deeb and Motulsky, 2011). It consists

of a number of plates, 24 or 38, the Ishihara plates, each containing a circle of dots which appear in

random color and size. Within the circle there are dots forming a number which should be clearly visible

to viewers with normal color vision and hard to see or invisible to viewers with defective color vision. To

pass the test participants should recognize the number in every plate. Examples of Ishihara plates are

presented in Appendix 1. The test was conducted in a separate room from the one in which the survey

took place in order to prevent our respondents from being aware of the importance of color in our

experiment and thus avoid any possible bias of the responses.

After discarding questionnaires that were incomplete or filled by color blind respondents 296 valid

responses were used for the analysis, with each color scheme being visited by 37 respondents. One

hundred and twelve answers were invalid and could not be used due to technical problems with the

browser that didn’t delete the temporary internet files folder. There were 32 color deficient participants,

which account for approximately 8% of the males in the sample. This percentage is equal to the actual

percentage of color deficient males in the world (Brémond, 2002). Color vision deficiency is sex-linked

and is mostly expressed in males whereas it is very rare in females. Males with color deficiencies have a

particular type of cone in the retina or one type of cone may be weak. Only forms of red-green color

blindness (protan and deutan defects) are encoded on the sex chromosome and occur more often among

men. Tritan defects and achromatopsia (complete color blindness) are evenly distributed between men

and women. Those forms of color deficiencies are not very common (Deeb, 2004).

18

12BRespondent characteristics

Participants were drawn randomly from a list of Design School of Nantes students and personnel who

had previously given their consent to participate in design experiments carried out in the prepared

laboratory. Students received course credits for their participation. The respondent characteristics are

presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Characteristics of the sample of respondents

Demographic

Characteristics

Category

Number of

respondents

Gender

Female

Male

160

136

Age

Under 25 years old

25 - 34 years old

35 - 44 years old

45 - 54 years old

55 - 64 years old

242

29

13

11

1

Internet

familiarity

Expert

Intermediate

Beginner

38

43

19

Education level

Certificate

High school

2nd-year university diploma

License / Master I /Master II

Postgraduate / doctorate / post-graduate / Master degree

no diploma

2

166

49

36

42

1

Profession

Executives and academics

Intermediate occupations

Manuel Workers

Students

Storekeepers and business managers

Pensioners

Other (to clarify)

32

3

2

244

4

1

10

Income per

month

From 0 to 500 euros

Under 1000 euros

From 1000 to 1399 euros

From 1400 to 1799 euros

From 1800 to 2199 euros

From 2200 to 2599 euros

247

15

11

5

9

9

The use of students as subjects has often been questioned in terms of their appropriateness as a sample.

However, in our study, students are deemed suitable as a sample, as they share many characteristics with

the profile of Internet users population, such as age. As shown by several studies, Internet users tend to

be young adults, while the Internet usage penetration within the age groups of 18-29 raises up to 95%

(Zickuhr, 2010; Pew Research Center, 2010). Hence, although our sample presents a bias towards

younger subjects, it can arguably be acceptable as representative of Internet users. In addition, our study

benefits from the use of students since they are considered as an important group of online consumers

(Delafrooz et al., 2010) and are useful as a sample for empirical studies in e-commerce, in line with

previous research (e.g. Kim et al., 2008).

Our sample would also arguably be stronger in terms of representativeness if it was cross cultural.

However, although the population of respondents was primarily native Continental French, it included

19

foreign students, with different cultures, as in any school or university settings. In this sense, our

sampling frame does not imply a serious threat to the validity and generalizability of our results.

However, a replication of the experiment with a more culturally diverse sample would allow for richer

data collection and findings.

13BExperiment design

Carrying out the experiment under laboratory conditions allows us to draw valid conclusions about the

groups surveyed (Jolibert and Jourdan, 2006). Internet enables one to conduct non-intrusive studies,

meaning that Internet users are not even aware that their behavior is being analyzed (Dreze and Zufryden,

1997). However, when conducting a study focusing on color, one has to control and neutralize three

major elements: screens, ambient light, and, above all, the participants’ color perception (Fernandez-

Maloigne, 2004). Since, these elements cannot be controlled in a distance study carried out over the

Internet, a controlled laboratory setting had to be used for our study. Screens were calibrated using a

probe to ensure that the colors were displayed as defined. The color of walls was neutral grey. The grey

color of the wall prevents a bad reflection of ambient light on the screens, which avoids color distortion

on the screen. By neutralizing the colors of both the ambient light and the walls we were confident that

we avoided any distortion. The brightness of the room was then set at 1000 lux to guarantee that the

colored appearance of the websites used for the experiment would not be biased by a too dim or a too

bright room light. Finally participants had to pass the Ishihara test for color blindness. Further, detailed

information how each of the three elements was controlled can be found in Appendix 1.

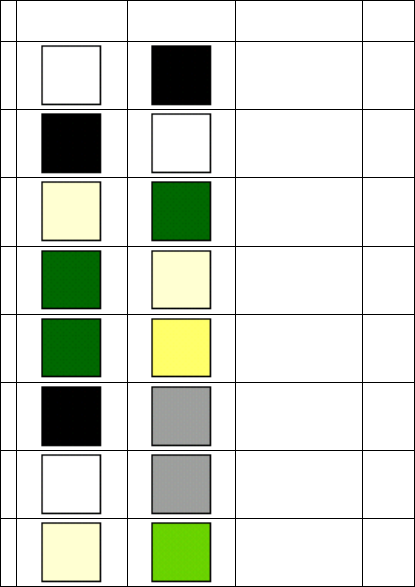

The experiment was a factorial design which included 8 treatments (4 x 2) related to 8 color schemes

developed for the experiment website (Table 6). In order to measure the differences in color perception,

we have created 8 different color schemes by varying hue and brightness and keeping the saturation rate

constant among the schemes. In accordance with Gorn et al. (2004), we set the saturation levels at 100%,

because at that level, the hues are most distinct. The color stimuli were modified in accordance with

Munsell’s (1969) system, considered as the most accurate one (Aumont, 1994), which enables defining

precisely several levels of brightness and saturation for each hue.

Several studies on the impact of culture on the behavior of Internet users and consumers draw attention to

the varying importance of design elements of a website across cultures (Maguire, 2011). Among these,

colors are a significant variable as their perception and impact is strongly influenced by culture. Colors

can convey different semantics depending on the cultural contexts (Filser 1994). Thus, culture is a

parameter that should be controlled in a study on the effects of colors of an e-commerce website. In order

to neutralize this aspect we based our experiment on a color selection driven by research on readability, a

characteristic which is not culture dependent (Hill and Scharff, 1997) .The design of the website was also

not too busy, leaving sufficient room for reading easily the commercial information as well as for

satisfying principles of website ergonomics such as the navigation bar and the search engine visibility.

An easy-to-read text on a screen, thanks to a sufficiently strong contrast between the background and

foreground color, is easier to memorize (Hall and Hanna, 2003; Scharff and Ahumada, 2002, Scharff and

Hill, 2000; Hill and Scharff, 1997). In order to validate that a combination of background and foreground

color was the best for memorization when the contrast was the strongest, we needed to rate each

combination of colors in terms of contrast ratio. We thus measured the latter to provide a gradient scale

between each combination of background and foreground color, which corresponds to a rank with “-“

and “+” symbols in Tables 5 and 6. We first differentiated each color scheme resulting in Table 5, which

was then used to produce Table 6 summarizing all the information required to explain the contrasts

ratios.

The contrast was measured by the Color Contrast Analyser (CCA) 1.1 for Web Pages of the Web

Accessibility Tools Consortium (WAT-C, 2005). Contrast ranks ranged from “+++” to “+”, for strong

ones and from “-“ to “--“ for low ones, according to the CCA. For example, a contrast ratio of 21 was

ranked as “+++” whereas a contrast of 1,82 was ranked as “-- “. CCA was created with the aim to design

easier to read web interfaces, in accordance with the W3C consortium. By taking into account the W3C

and Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) guidelines, the use of color becomes more professional and the

20

choices web designers make are more informed in terms of usability, as well as in terms of human

computer interaction in general.

Table 6: Contrast ratio order according to color schemes

Background

Foreground

Contrast ratio

Rank

1

21

+++

2

21

+++

3

6,95

++

4

6,95

++

5

6,71

++

6

3,26

+

7

2,65

--

8

1,82

--

To set our first experiment treatment we used the color scheme used by Hill and Scharff (1997) which

supported the best readability rate in relation to contrast and we chose as chromatic colors a yellow

background (Magnolia yellow) and a green foreground (Newsvine green). Starting from this scheme, we

reduced the brightness level of the two colors so as to obtain the second experiment treatment. For

experiment treatments 3 and 4 we kept the same colors but switched foreground and background colors.

Experiment treatments 5, 6, 7 and 8 are based on black and white (achromatic colors), the most

frequently used colors on e-commerce websites. Brightness and saturation levels were identical with

those used for chromatic colors in experiment treatments 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively (Table 7).

21

Table 7: Factorial Design of the Experiment

Plan

Background

Foreground

Contrast

Plans explanations

Name

H

B

S

Name

H

B

S

1

Magnolia

Yellow

60

100

20

Newsvine

Green

120

40

100

6,95*

Passed at

Level 2

(++)

(Hill and Scharff, 1997) showed that the sharp

contrasts of this scheme offered users the fastest

reading speed possible among chromatic colors.

Hex.

#FFFFD0

#006700

2

Magnolia

Yellow

60

100

20

Granny Apple

Green

90

80

100

1,82*

Fail

(--)

Same color scheme as in the Plan 1 with an

increased foreground color brightness (from 40 to

80).

Hex.

#FFFFD0

#6BD500

3

Newsvine

Green

120

40

100

Magnolia

Yellow

60

100

20

6,95*

Passed at

Level 2

(++)

Same colors as in Plan 1. Foreground and

background colors were switched.

Hex.

#006700

#FFFFD0

4

Newsvine

Green

120

40

100

Sunflower

Yellow

60

100

60

6,71*

Passed at

Level 2

(++)

Same color’s scheme as in Plan 3 with an increase

in foreground color saturation (from 20 to 60). The

color which should have been used for the text of

the experimental plan 4, in order to preserve rates of

luminosity and saturation in relation to the

background color, could not be preserved. Indeed,

this scheme could not be used given the lack of

contrast between the two colors

(foreground/background) which made the reading

impossible on a more or less old or difficult screen,

for individual presenting deficiencies with color's

vision we refer to the directives of the w3c. We thus

varied its degree of saturation.

Hex.

#006700

#FFFF6B

5

White

0

100

0

Black

0

0

0

21,00*

Passed at

Level 3

(+++)

This scheme is the most widely used one on e-

commerce websites.

Hex.

#FFFFFF

#000000

6

White

0

100

0

Grey

0

60

0

2,65*

Fail

(--)

Same color scheme as Plan 5 with increased

foreground color brightness (from 0 to 60).

Hex.

#FFFFFF

#9C9E9E

7

Black

0

0

0

White

0

100

0

21,00*

Passed at

Level 3

(+++)

Same colors as in Plan 5. Foreground and

background colors have been switched.

Hex.

#000000

#FFFFFF

8

Black

0

0

0

Grey

0

60

0

3,26*

Fail

(+)

Same scheme as in Plan 7 with a decrease in

foreground color brightness (from 100 to 60).

Hex.

#000000

#9C9E9E

* Text or diagrams and their background must have a luminosity contrast ratio of at least 5:1 for level 2 conformance to

guideline 1.4

22

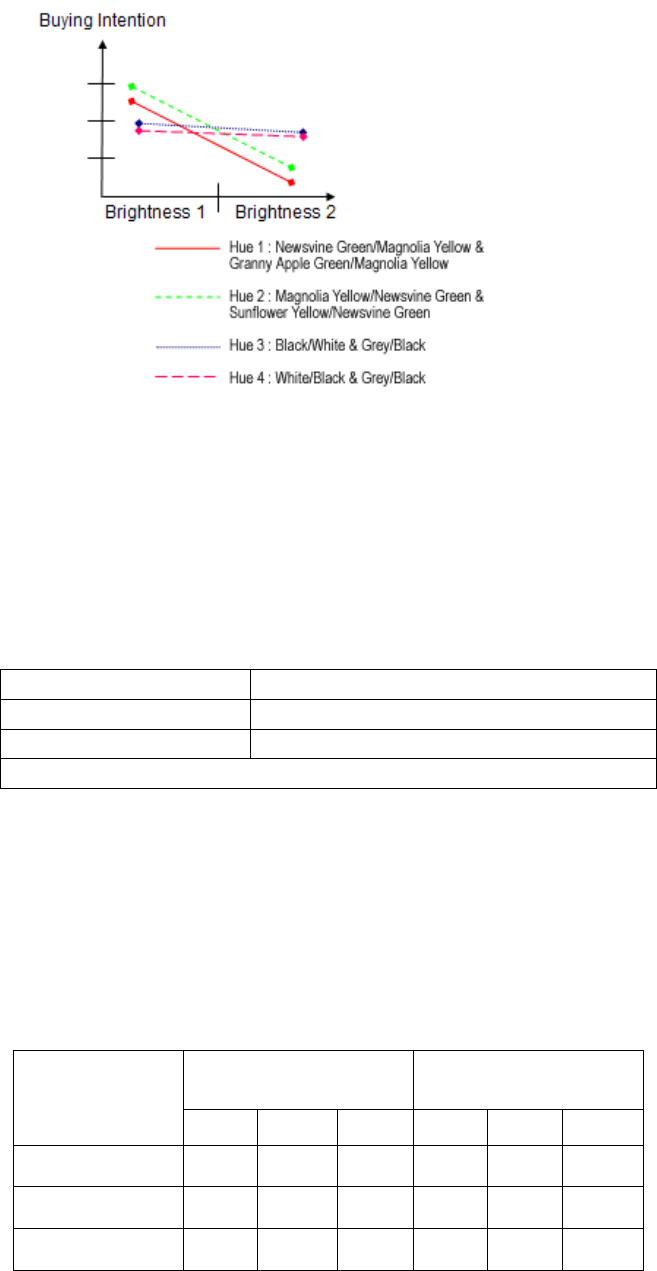

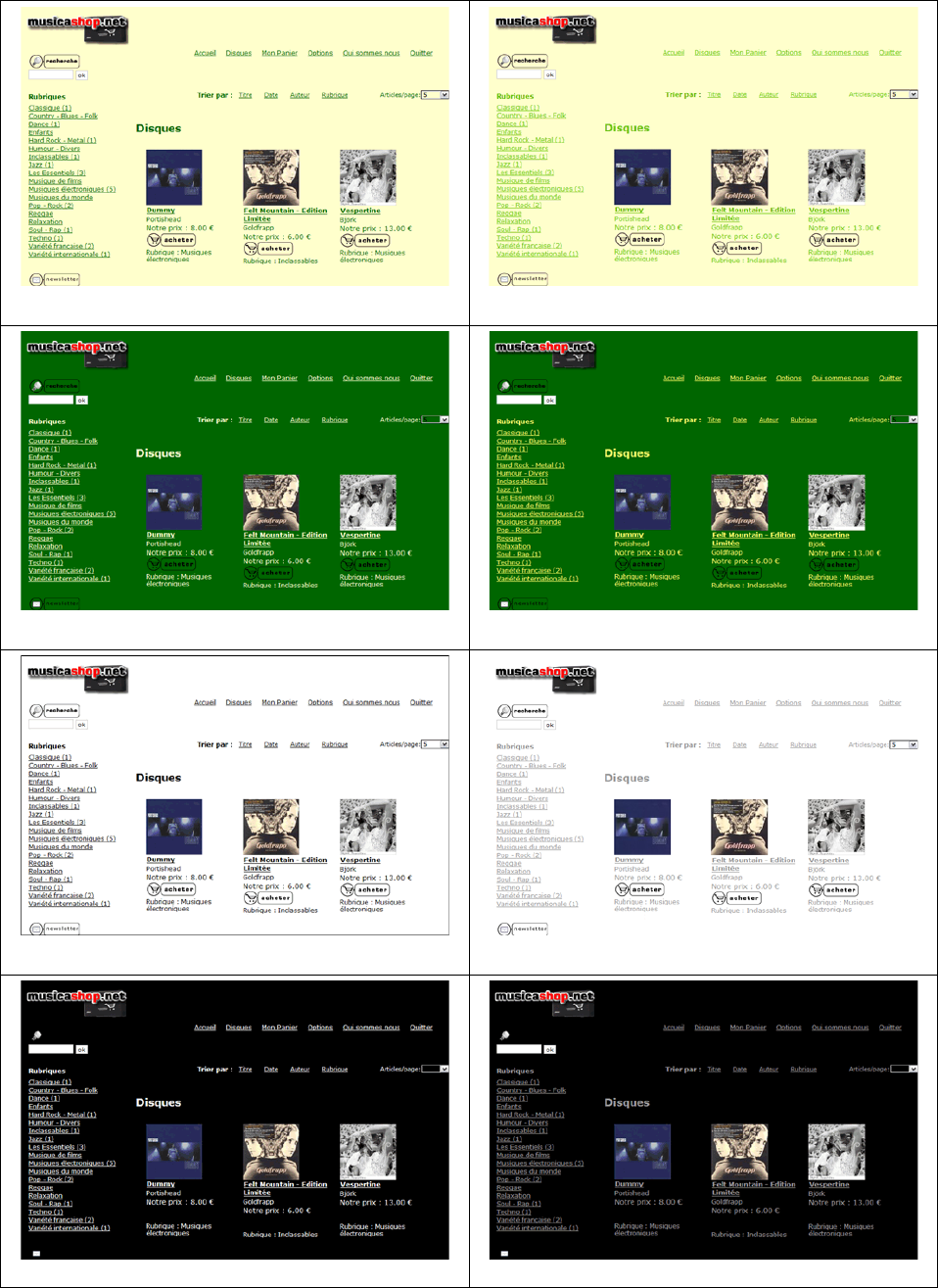

Figure 2 shows a screenshot of our experiment website. In this particular example, the background color

is Magnolia Yellow and the foreground color is Newsvine Green representing experiment plan 1. As it

can be seen, the experiment website didn’t have any other colors than the foreground and background

ones. The design was simple, with very limited use of graphics such as the store logotype and the

shopping cart logotype, in order to reveal only the colors selected for the color scheme of each factorial

plan (background, foreground). Screenshots of the experiment website for each of the 8 plans are

provided in Appendix 2.

Figure 2: Experiment website

14BMeasures

26BMemorization

Memorization was measured by measuring recognition, cued recall and free recall.

To measure recognition, participants were asked to recognize two CD covers, each among two other

covers of different albums by the same artist. Recognition scores ranged from 0 to 2, one for each CD

cover they could recognize. Measuring recognition was not deemed useful since the participants

answered to the questionnaires a few minutes after visiting the e-commerce website and 100% of them

recognized both CD covers. Thus, we decided not to include recognition further in our analysis.

Cued recall was measured by asking the respondents to answer to a question with 3 alternative values

(correct, wrong and “I don’t know”) for each of the seven information items related to a CD cover.

Scores could thus be graded from 0 to 7 for each item visited. Since participants were required to check

out two CD covers, scores for cued recall ranged from 0 to 14.

In order to measure free recall, participants were asked to answer to an open-ended question related to an

image about the CD cover they had just seen. The question was “What do you remember from the

information associated with this CD cover?”. Free recall was measured by counting the number of the

items that participants could recall from those used in the CD description. Since participants could see

two CD covers, each having a 20-element description, free recall value ranged from 0 to 40.

23

The score of commercial information memorization was the sum of the recognition score, cued recall

score and free recall score, ranging from 0 to 56.

27BMood

To measure mood we used Mayer and Gaschke’s (1988) Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS).

Participants were asked to reply to the question “Do you feel _______?” for a list of 16 items rated on a

5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Definitely do not feel’ (1) to ‘Definitely feel’ (5), and for each of the

16 items select the answer that best expressed their mood. We selected to use BMIS because it provides a

quite exhaustive range of moods and is easy to supervise. The scale and its validity and reliability are

presented in Appendix 3.

Each participant passed a pre-test administrated before the start of the experiment. This pre-test measured

mood, using BMIS, in order to enable linking the affective states of the participants with the website