BUILDING COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

WITH NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

A GUIDE FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES

JUNE 2021

Natural hazards pose a serious risk to states, localities, tribes and territories throughout the United States. These hazards

include ooding, drought, hurricanes, landslides, wildres and more. Because of climate change, many natural hazards are

expected to become more frequent and more severe. Reducing the impacts these hazards have on lives, properties and

the economy is a top priority for many communities.

Nature-based solutions are sustainable planning, design, environmental management, and engineering practices that weave

natural features or processes into the built environment to promote adaptation and resilience. Such solutions enlist natural

features and processes in efforts to combat climate change, reduce ood risks, improve water quality, protect coastal

property, restore and protect wetlands, stabilize shorelines, reduce urban heat, add recreational space, and more.

Nature-based solutions offer signicant benets, monetary and otherwise, often at a lower cost than more traditional

infrastructure. These benets include economic growth, green jobs, increased property values, and improvements to public

health, including better disease outcomes and reduced injuries and loss of life.

The implementation strategies for nature-based solutions are diverse;

one size does not t all. Choosing a solution depends on a number of

factors, including the level of natural hazard risk reduction, land use

planning, economics and more. The following are examples of nature-

based solutions:

• In Tucson, Arizona, almost 45% of the city’s water is used for

outdoor (non-potable) purposes. The city of Tucson’s Commercial

Rainwater Harvesting Ordinance aims to reduce this demand. It

requires commercial property developers to harvest rainwater for

at least 50% of their landscaping needs.

• The GreenSeams program in greater Milwaukee, Wisconsin, permanently keeps oodprone lands in high-growth areas

from being developed. Since 2001, the program has preserved more than 3,000 acres of land that can store 1.3 billion

gallons of water.

• Los Angeles, California, saw an increase of more than 2,000 jobs from its $166 million investment in nature-based

solutions from 2012 to 2014. Many of these jobs are local, providing an extra boost to the local economy.

• The Quabbin and Wachusett reservoirs serve 2.5 million people in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Water Resources

Authority has spent $130 million over the past 20 years on nature-based solutions. These solutions protect

22,000 acres of the watershed that drains into nearby reservoirs. A water ltration plant would have cost $250 million

to build and $4 million annually to operate and maintain.

The primary goal of this guide is to help communities identify and engage the staff and resources that can be used to

implement nature-based solutions to build resilience to natural hazards, which may be exacerbated by climate change.

At the Department, we must — and

we will — do more to address the

climate crisis. DHS will implement a

new approach to climate change

adaptation and resilience, and we will

do so with the sense of urgency this

problem demands.

– Secretary of Homeland Security

Alejandro N. Mayorkas

LEVERAGING NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

IN AN ERA OF CLIMATE CHANGE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................... 2

Goal of the Guide ................................................................................................................................................. 3

Structure of the Guide .......................................................................................................................................... 3

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS? .................................................................................................................... 4

Types of Nature-Based Solutions .......................................................................................................................... 5

Watershed or Landscape Scale ............................................................................................................................. 6

Neighborhood or Site Scale .................................................................................................................................. 7

Coastal Areas ....................................................................................................................................................... 8

THE BUSINESS CASE .................................................................................................................................................. 9

Hazard Mitigation Benefits .................................................................................................................................... 9

Community Co-Benefits .......................................................................................................................................11

Community Cost Savings .................................................................................................................................... 13

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE .................................................................................................................. 14

Land Use Planning ...............................................................................................................................................14

Hazard Mitigation Planning ................................................................................................................................. 15

Stormwater Management .....................................................................................................................................16

Transportation Planning .......................................................................................................................................17

Open Space Planning.......................................................................................................................................... 18

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE ......................................................................................................................................... 19

Boosting Public Investment ................................................................................................................................. 19

Incentivizing Private Investment .......................................................................................................................... 22

FEDERAL FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES ........................................................................................................................ 25

KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES ............................................................................................................ 28

RESOURCES ............................................................................................................................................................. 29

FEMA would like to express appreciation to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) nature-based solutions

and coastal community resilience subject matter experts who provided their valuable and constructive suggestions during the

development of this resource. Their willingness to devote their time and expertise so generously to enhance the impact of this

resource for communities is greatly appreciated.

COVER PHOTO: Buffalo Bayou Park in Houston, TX. The park serves as both critical flood infrastructure and an important recreational and cultural

asset for the downtown area. The popular park stretches 2.3 miles along the floodprone Buffalo Bayou and includes trails, public art installations,

gardens, two festival lawns, a skate park, and a restaurant. In the park’s first year, a survey counted nearly 150,000 trail users in a single month.

|

2

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Hatteras, NC. The Durant’s Point living shoreline project protects the shoreline from storm surge while providing habitat for many species. Since its

construction, the project has weathered hurricanes, a summer of drought, and tropical storms. Photo: N.C. Coastal Federation

Nature-based solutions weave natural features and

processes into a community’s landscape through planning,

design, and engineering practices. They can promote

resilience and adaptation while being integrated into a

community's built environment (for example, a stormwater

park) or its natural areas (for example, land conservation).

While nature-based solutions have many hazard mitigation

benets, they can also help a community meet its climate,

social, environmental, and economic goals. Communities

across the country are nding nature-based solutions to be

a highly effective way to provide public services that were

traditionally met with structural or “gray” infrastructure.

Local ofcials and their partners are using nature-based

solutions to improve water quality in Lenexa, Kansas; to

reduce ood risks in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; to limit erosion

in coastal North Carolina; and to provide neighborhood

amenities in Houston, Texas.

FEMA and its federal partners produced the

National Mitigation Investment Strategy to increase

our nation’s resilience to natural hazards. Its

purpose is to coordinate the use of federal, state,

local, and private resources to help communities

survive and thrive in the face of natural disasters.

This Guide builds on the three key goals of the

Investment Strategy.

1. To motivate communities to invest in mitigation (for

example, by showing how to measure its value);

2. To shrink barriers to investing in mitigation (for

example, by improving access to risk information

and funding); and

3. To make investing in mitigation standard practice

(for example, by considering mitigation in all

investment decisions for public infrastructure).

Flooding, high wind, drought, landslides, and other natural hazards pose major threats to communities

across the United States. Natural disasters are becoming more frequent and more costly as a result

of climate change. Reducing the threats these disasters pose to lives, properties, and the economy

is a top priority for many communities. The National Mitigation Investment Strategy identies nature-

based solutions as a cost-effective approach to keep natural hazards from becoming costly disasters.

The promise of nature-based solutions comes from the many benets they offer and the many partners

they can draw to the table.

|

3

INTRODUCTION

GOAL OF THE GUIDE

The key goal of this guide is to help communities identify and engage the staff and resources that can be used to

implement nature-based solutions to build resilience to natural hazards, which may be exacerbated by climate change.

Planning and building cost-effective nature-based solutions will require collaboration. Many departments may need to be

involved in planning and carrying out the strategies in this guide. Consider including the following local government partners:

In addition, non-governmental community partners like civic associations, watershed groups, and non-prot organizations

should be involved in the planning process. They may have the capacity to customize and implement nature-based solutions.

The focus of this guide is local communities, but many of the ideas and advice may also apply to state, territorial, and

tribal governments.

STRUCTURE OF THE GUIDE

Some local communities may use this guide to learn about nature-based solutions and weigh their value for the community.

Others may be ready to move from planning to action. The guide includes six sections, and users can jump in at any point,

depending on their current knowledge base and interests. The six sections are described below.

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

Describes three broad categories of nature-based solutions.

Identies types of nature-based solutions in each category.

THE BUSINESS CASE

Outlines the many hazards that can be mitigated with nature-based solutions.

Discusses the multiple benets of nature-based solutions, in addition to hazard mitigation.

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

Identies planning processes and programs that can help users invest in nature-based solutions.

Discusses how plans and policies can be updated to allow and encourage nature-based solutions.

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

Reviews how local resources can be mobilized to preserve, restore, and build nature-based solutions.

Discusses innovative ways of promoting private investment.

FEDERAL FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES

Outlines federal funding sources for nature-based solutions.

Emphasizes FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) grant programs.

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND RESOURCES

Summarizes key points for communities.

Provides additional resources.

• Parks and Recreation

• Public Works

• Planning and Economic Development

• Environmental Protection

• Utilities

• Transportation

• Floodplain Administration

• Emergency Management

|

4

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

Green Infrastructure and Low Impact Development

Some organizations use the term green infrastructure

to capture the value and functions of natural lands. For

example, the Conservation Fund denes green infrastructure

as “a strategically planned and managed network of natural

lands, working landscapes, and other open spaces that

conserves ecosystem value and functions and provides

associated benets to human populations.”

Other organizations use the term green infrastructure for

nature-based solutions to urban stormwater pollution. These

organizations emphasize solutions that protect water quality

and aquatic habitat. The other outcomes, such as mitigating

natural hazards, are seen as co-benets. Low impact

development is another term that is often used to describe

nature-based solutions for urban stormwater. In the eld of

stormwater management, “green infrastructure” and “low

impact development” are sometimes used interchangeably.

Natural Infrastructure

The term “natural infrastructure” is often used to describe

natural or naturalized landscapes that are actively

managed to provide multiple benets to communities.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development,

a think tank, notes that active management is what sets

natural infrastructure apart from nature. For example,

a managed wetland is a type of natural infrastructure.

Manipulating water levels and cleaning out plant growth

can enhance a managed wetland’s water quality, habitat,

and ood storage benets.

Engineering with Nature

Organizations that design and operate water infrastructure

projects may also refer to Engineering with Nature®, a

term that comes from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’

(USACE) Engineering with Nature Initiative. This term

refers to water resources projects that use collaborative

approaches to project design and operation to create

multi-functional infrastructure. Engineering with Nature®

can result in projects that deliver a broader range of

economic, ecosystem services, and social benets.

Bioengineering

Bioengineering is a term that is used to describe projects

that mimic natural processes in order to reduce hazards.

An example of bioengineering would be using a combination

of natural and manmade materials to stabilize a slope,

giving vegetation a chance to become established to

reduce future erosion.

Tying It All Together

The common thread among these terms is that

nature-based solutions often provide more value than

single-purpose gray infrastructure. Gray infrastructure

refers to public works structures that are engineered to

provide a specic level of service under specic scenarios.

In the context of drinking water and wastewater, gray

infrastructure includes water and wastewater treatment

plants, pipes, catch basins, and stormwater basins. In

the context of coastal communities, gray infrastructure

This guide defines nature-based solutions as sustainable planning, design, environmental management,

and engineering practices that weave natural features or processes into the built environment to build more

resilient communities. While this guide uses the term nature-based solutions, other organizations use related

terms, such as green infrastructure, natural infrastructure, or Engineering with Nature®, a program of the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers. As a best practice, use the term that best resonates with your target audience.

|

5

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

CATEGORIES OF NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

This guide categorizes nature-based solutions practices based on scale and location:

• WATERSHED OR LANDSCAPE SCALE: Interconnected systems of natural areas and open space. These are

large-scale practices that require long-term planning and coordination.

• NEIGHBORHOOD OR SITE SCALE: Distributed stormwater management practices that manage rainwater

where it falls. These practices can often be built into a site, corridor, or neighborhood without requiring

additional space.

• COASTAL AREAS: Nature-based solutions that stabilize the shoreline, reducing erosion and buffering the

coast from storm impacts. While many watershed and neighborhood-scale solutions work in coastal areas,

these systems are designed to support coastal resilience.

The illustrations on the following pages are examples of nature-based solutions and do not cover all options.

Rain Garden — City Hall in Bay Village, OH

includes sea walls, groins, and breakwaters. While gray

infrastructure provides only the service for which it

was designed, nature-based solutions yield additional

community and ecosystem services benets.

Ecosystem services is a term used to describe

all of the benets that we get from the environment

— everything from air, food, and water to the

enjoyment of nature and natural resources.

|

6

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

WATERSHED SCALE

LAND CONSERVATION

Land conservation is one way

of preserving interconnected

systems of open space that

sustain healthy communities.

Land conservation projects begin

by prioritizing areas of land for

acquisition. Land or conservation

easements can be bought or

acquired through donation.

GREENWAYS

Greenways are corridors of protected

open space managed for both

conservation and recreation.

Greenways often follow rivers or other

natural features. They link habitats

and provide networks of open space

for people to explore and enjoy.

FLOODPLAIN RESTORATION

Undisturbed oodplains help

keep waterways healthy by

storing oodwaters, reducing

erosion, ltering water pollution,

and providing habitat.

Floodplain restoration rebuilds

some of these natural functions

by reconnecting the oodplain

to its waterway.

WETLAND RESTORATION

AND PROTECTION

Restoring and protecting wetlands

can improve water quality and

reduce ooding. Healthy wetlands

lter, absorb, and slow runoff.

Wetlands also sustain healthy

ecosystems by recharging

groundwater and providing

habitat for sh and wildlife.

STORMWATER PARKS

Stormwater parks are recreational

spaces that are designed to ood

during extreme events and to

withstand ooding.

By storing and treating oodwaters,

stormwater parks can reduce ooding

elsewhere and improve water quality.

|

7

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

NEIGHBORHOOD OR SITE SCALE

RAINWATER HARVESTING

Rainwater harvesting systems

collect and store rainfall for later

use. They slow runoff and can reduce

the demand for potable water.

Rainwater systems include rain

barrels that store tens of gallons

and rainwater cisterns that store

hundreds or thousands of gallons.

GREEN ROOFS

A green roof is tted with a planting

medium and vegetation. A green roof

reduces runoff by soaking up rainfall.

It can also reduce energy costs for

cooling the building.

Extensive green roofs, which have

deeper soil, are more common on

commercial buildings. Intensive green

roofs, which have shallower soil, are

more common on residential buildings.

TREE TRENCHES

A stormwater tree trench is a row

of trees planted in an underground

inltration structure made to store

and lter stormwater.

Tree trenches can be added to

streets and parking lots with limited

space to manage stormwater.

GREEN STREETS

Green streets use a suite of green

infrastructure practices to manage stormwater

runoff and improve water quality.

Adding green infrastructure features to

a street corridor can also contribute to

a safer and more attractive environment

for walking and biking.

TREE CANOPY

Tree canopy can reduce stormwater

runoff by catching rainfall on

branches and leaves and increasing

evapotranspiration. By keeping

neighborhoods cooler in the summer,

tree canopy can also reduce the

“urban heat island effect.”

Because of trees’ many benets, many

cities have set urban tree canopy goals.

PERMEABLE PAVEMENT

Permeable pavements allow more

rainfall to soak into the ground.

Common types include pervious

concrete, porous asphalt, and

interlocking pavers.

Permeable pavements are most

commonly used for parking lots

and roadway shoulders.

RAIN GARDENS

A rain garden is a shallow, vegetated

basin that collects and absorbs

runoff from rooftops, sidewalks,

and streets.

Rain gardens can be added around

homes and businesses to reduce

and treat stormwater runoff.

VEGETATED SWALES

A vegetated swale is a channel

holding plants or mulch that treats

and absorbs stormwater as it ows

down a slope.

Vegetated swales can be placed along

streets and in parking lots to soak up and

treat their runoff, improving water quality.

|

8

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS?

DUNES

Dunes are coastal features made

of blown sand. Healthy dunes

often have dune grasses or other

vegetation to keep their shape.

Dunes can serve as a barrier

between the water’s edge and

inland areas, buffering waves

as a rst line of defense.

WATERFRONT PARKS

Waterfront parks in coastal areas

can be intentionally designed

to ood during extreme events,

reducing ooding elsewhere.

Waterfront parks can also absorb

the impact from tidal or storm

ooding and improve water quality.

LIVING SHORELINES

Living shorelines stabilize a shore

by combining living components,

such as plants, with structural

elements, such as rock or sand.

Living shorelines can slow

waves, reduce erosion, and

protect coastal property.

COASTAL AREAS

COASTAL WETLANDS

Coastal wetlands are found

along ocean, estuary, or

freshwater coastlines.

They are often referred to as

“sponges” because of their ability

to absorb wave energy during

storms or normal tide cycles.

OYSTER REEFS

Oysters are often referred to as

“ecosystem engineers” because

of their tendency to attach to hard

surfaces and create large reefs made

of thousands of individuals.

In addition to offering shelter and

food to coastal species, oyster reefs

buffer coasts from waves and lter

surrounding waters.

|

9

THE BUSINESS CASE

THE BUSINESS CASE

HAZARD MITIGATION BENEFITS

Nature-based solutions can help reduce the loss of life

and property resulting from some of our nation’s most

common natural hazards. These include ooding, storm

surge, drought, and landslides. As future conditions, like

climate change, amplify these hazards, nature-based

solutions can help communities adapt and thrive.

Riverine Flooding

Communities can mitigate riverine ooding by investing in

watershed-scale practices. Land conservation, oodplain

restoration, and waterfront parks can keep development

out of harm’s way. They also store and slow oodwaters.

Urban Drainage Flooding

When the amount of stormwater owing into a community’s

storm sewer system exceeds the system’s capacity, water

can back up and ood streets, basements, and homes. This

type of ooding is most common where new development

and changing rainfall patterns produce more runoff than

the system was designed to handle. While urban drainage

ooding is often less damaging than riverine ooding,

it also tends to be more frequent. Over time, repeated

minor oods can cost a community more than the extreme

oods. They can also decrease real estate values and drive

businesses away. Communities can mitigate this type of

ooding by encouraging or requiring neighborhood- and

site-scale nature-based solutions like bioretention systems.

Bioretention systems include practices such as rain

gardens, rainwater harvesting, green roofs, and more. These

practices soak up runoff from hard surfaces and reduce the

amount of stormwater owing into the storm sewer system.

The GreenSeams program in greater Milwaukee,

Wisconsin permanently keeps oodprone lands

in high-growth areas from being developed. Since

2001, the GreenSeams program has preserved

more than 3,000 acres of land that can store

1.3 billion gallons of water.

In Huntington, West Virginia, many neighborhoods

experience ooding after heavy rainfalls. The

city’s comprehensive plan recommends using

nature-based solutions that manage stormwater

onsite to reduce the burden to the storm sewer

system and reduce ooding.

In response to natural hazards and to proactively address climate related risks, many communities

are looking for ways to build resilience that yield the most benet for the least cost. This section builds

the business case for nature-based solutions by summarizing their potential cost savings and their

non-monetary benets. Thoughtfully planned nature-based solutions can contribute to a community’s

triple bottom line, providing social, environmental, and nancial value.

|

10

THE BUSINESS CASE

Coastal Flooding and Storm Surge

Coastal ooding can be caused by unusually high tides,

strong winds, or storm surge. As future conditions lead to

more intense storms and rising sea levels, coastal ooding

is becoming more frequent and storm surges are becoming

more severe. Communities can mitigate coastal ooding

by investing in nature-based shoreline stabilization. Living

shorelines, reefs, and dunes can slow waves, reduce

wave height, and reduce erosion. At the same time, these

practices benet the ecosystem by ltering and cleaning

water and providing habitat.

Drought

Droughts are also expected to be amplied by future

conditions. As precipitation patterns become more

unpredictable, communities can increase their resilience.

Two options are conservation and rainwater harvesting.

Conservation is a watershed-scale approach. It preserves

or restores rainwater inltration to increase groundwater.

At the site scale, rainwater harvesting can help. It offsets

some of the demand for non-potable water. This demand

can be further reduced by xeriscaping, or drought-tolerant

landscaping.

Landslides

Landslide hazards tend to be highest in steeply sloped

areas. They are particularly high when soils are saturated

and vegetation has decreased, or as a result of res

and droughts. At the watershed scale, communities can

reduce landslide threats through conservation aimed at

steeply sloped land. At the neighborhood and site scale,

communities can invest in green stormwater infrastructure

and bioretention systems. This includes trees, rain gardens,

bioswales, inltration basins, and pervious pavement. These

stabilize slopes by keeping them drier and adding vegetation

and root structures.

In Tucson, Arizona, almost 45 percent of the city’s

water is used for outdoor (non-potable) purposes.

The City of Tucson’s Commercial Rainwater

Harvesting Ordinance aims to reduce this demand.

It requires commercial property developers to

harvest rainwater for at least 50 percent of their

landscaping needs.

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

lists stabilizing slopes using native vegetation and

drainage improvements as one way to mitigate

landslide hazards.

According to a 2014 journal article in Ocean &

Coastal Management, North Carolina properties

with natural shoreline protection measures

withstood wind and storm surge during Hurricane

Irene (2011) better than properties with seawalls

or bulkheads. The storm damaged 76 percent of

bulkheads surveyed, while there was no detected

damage to other shoreline types.

Mud slide with rock, boulders, and debris

|

11

THE BUSINESS CASE

COMMUNITY CO-BENEFITS

The biggest selling points for nature-based solutions are

their many benets beyond mitigating the effects of natural

hazards. Nature-based solutions can provide short- and

long-term environmental, economic, and social advantages

that improve a community’s quality of life and make it more

attractive to new residents and businesses. Unlike gray

infrastructure, a single nature-based project can yield a

variety of community benets that fulll many departments’

goals. Local leaders can highlight these co-benets to

encourage collaboration and make nature-based solutions

standard practice. The bottom line is that collaboration on

nature-based solutions can help communities survive in the

long-term and thrive day-to-day.

Ecosystem Services

• Improved water quality: Nature-based solutions can be

used to lter pollutants from stormwater runoff and to

reduce the volume of polluted water owing into rivers,

lakes, and coastal waters. In older cities with combined

sewer systems, they can also reduce the untreated

sewage going into community waterways. Combined

sewer systems send all stormwater and sewage to a

wastewater treatment plant before releasing the treated

wastewater into waterways. When it rains, these systems

sometimes carry more water than the treatment plant can

handle. As a result, some of the mixed stormwater and

sewage will be released untreated into waterways. These

events are called combined sewer overows (CSOs).

By lowering the volume of rainwater owing into a

combined sewer system, Nature-based solutions can

reduce CSOs and improve water quality.

•

Cleaner water supplies: Nature-based solutions that

protect the land around drinking water reservoirs can

keep polluted runoff away from a community’s water

supply. New York City has high-quality tap water because

the city invested in nature-based solutions around its

19 reservoirs. The city’s $600 million investment to

conserve and restore the land keeps the water draining

into the reservoirs clean. It provided the same level of

service as the $6 billion water ltration plant that the city

would have needed otherwise.

•

Improved air quality: Trees, parks, and other plant-based,

nature-based solutions can absorb and lter pollutants

and reduce air temperatures. Doing so reduces smog and

improves air quality.

•

Healthier wildlife habitats: Watershed and shoreline

nature-based solutions preserve open space and

natural environments. If thoughtfully designed, they

can also connect habitats to give plants and animals

more space to move across the landscape. Both types

of nature-based solutions protect aquatic and wildlife

habitats by improving water quality.

Economic Benefits

• Increased property values: If a property is near a park

or has more landscaping, it generally has a higher value.

A study of 193 public parks in Portland, Oregon found

that parks had a signicant, positive impact on nearby

property values. A park within 1,500 feet of a home

increased its sale price by $1,290 to $3,455 (adjusted

to 2020 dollars). As parks increased in size, their impact

on property value grew.

• Improved property tax base: Nature-based solutions

can improve the tax base in both high-growth and

low-growth communities. In high-growth areas,

nature-based features translate into a higher property

tax base. In low-growth communities, nature-based

solutions can stabilize property values in areas with

high vacancies.

The City of Lenexa, Kansas focuses on

nature-based solutions to prevent stormwater

pollution and reduce stormwater runoff.

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, vacant lots were

found to deate neighborhood property values

by as much as 20 percent. The Pennsylvania

Horticultural Society initiated a program to green

and maintain vacant lots. This program now

maintains about 7,000 parcels totaling 8 million

square feet. A 2012 study of the program found

that homes within a quarter mile of a greened lot

increased in value by 2 to 5 percent annually –

generating $100 million in additional annual

property taxes.

|

12

THE BUSINESS CASE

• Green jobs: Green stormwater infrastructure creates

new job opportunities in sectors like landscape

design, paving, and construction. It also opens new

job opportunities in emerging industries.

•

Improved triple bottom line: The triple bottom line is

an accounting framework that measures the value of

social and environmental benets, as well as nancial

benets. Nature-based solutions often provide more

triple bottom line benets than traditional, gray

infrastructure. As a result, they increase a community's

return on investment, an especially important factor

when considering climate change.

Social Benefits

• Cooler localized temperatures: Built-up areas tend to be

hotter than nearby rural areas, particularly on summer

nights. The “urban heat island effect” can lead to higher

rates of heat-related illness. Adding trees and vegetation

can help reduce these effects on hot days by providing

shade and cooling through evapotranspiration.

•

Improved public health: Many of the environmental and

social benets of nature-based solutions also benet

public health, including mental health. Improved air and

water quality reduce exposure to harmful pollutants.

Cooler summer temperatures reduce the risk of

heat-related illness. Additional recreation spaces increase

opportunities for physical activity and social engagement.

•

Added recreational space: Nature-based solutions

that preserve and enhance open space provide more

areas for recreation. In addition, nature-based solutions

such as greenways and green streets can increase

opportunities for active transportation, such as biking

and walking. These spaces can also provide aesthetic

benets that contribute to improved mental health and

physical well-being.

Los Angeles, California saw an increase of more

than 2,000 jobs from its $166 million investment

in nature-based solutions from 2012-2014. The

best part about this job growth is that many of

these jobs are local, providing an extra boost to

the local economy.

Hunter’s Point South Park in Queens, New York

City gives residents a new space to play and relax

outdoors, while also mitigating ood risk along

the East River. Nature-based features include

bioswales and street-side stormwater planters

to slowly absorb and release stormwater, and

1.5 acres of new wetlands to shield upland areas

from storm surge.

Hunter's Point South Park, a part of Gantry Plaza State Park, NY

|

13

THE BUSINESS CASE

COMMUNITY COST SAVINGS

The nal piece of the business case for nature-based solutions

is the potential for cost savings. Savings may come when

nature-based solutions cost less than alternative investments,

avoid the need for certain infrastructure altogether, reduce

the cost of rebuilding and repairs after a disaster, and help

mitigate the impacts of future conditions like climate change.

It is important to emphasize that it is often, but not always,

possible to identify nature-based approaches that are

cheaper than gray infrastructure alternatives.

Avoided Flood Losses

Nature-based solutions can also help communities save

money by reducing losses from future oods and other

natural disasters. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) studied this issue in a landmark 2015 study. The study

estimated the ood losses that would be avoided nationwide

by adding requirements to manage stormwater onsite. It

found that, over time, using nature-based solutions in new

development and redevelopment could save hundreds of

millions of dollars in ood losses.

Reduced Stormwater Management Costs

Using nature-based infrastructure can reduce the cost

of stormwater management for new development because

material costs are lower. Nature-based solutions can

reduce the need for expensive below-ground infrastructure.

They can also reduce the number of curbs, catch basins,

and outlet control structures required. Nature-based

solutions can save money on site preparation because

they requires less land disturbance.

In older cities with combined sewer systems, using both

green and gray infrastructure can reduce combined sewer

overows (CSOs) at a lower cost. The traditional, gray

infrastructure approach is to install below-ground tanks and

tunnels and expand existing facilities. This process has

extremely high capital costs. It also delays water quality

improvements until the end of a decades-long design and

construction process. Many nature-based solutions practices

have lower capital costs and begin to provide benets in a

few years. New York City developed a plan to reduce CSOs

using both green and gray infrastructure. The nature-based

solutions component will eventually capture runoff from

10 percent of the impervious areas of the combined sewer

watersheds. While the gray infrastructure option would

cost about $3.9 billion in public funds, the nature-based

alternative will cost about $1.5 billion.

In older cities with combined sewer systems, using both

green and gray infrastructure can reduce combined sewer

overows at a lower cost. The traditional, gray infrastructure

approach is to install below-ground tanks and tunnels and

expand existing facilities. This process has extremely high

capital costs. It also delays water quality improvements until

the end of a decades-long design and construction process.

Many NBS practices have lower capital costs and begin to

provide benets in a few years. New York City developed a

plan to reduce CSOs using both green and gray infrastructure.

The NBS component will eventually capture runoff from

10 percent of the impervious areas of the combined sewer

watersheds. While the gray infrastructure option would cost

about $3.9 billion in public funds, the NBS alternative will

cost about $1.5 billion.

Reduced Drinking Water Treatment Costs

Watershed-scale conservation practices can keep drinking

water clean. They are often more cost-effective than building

ltration plants to treat polluted water.

The Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs serve 2.5

million people in central Massachusetts and the

Boston area. Over 20 years, the Massachusetts

Water Resources Authority spent $130 million on

nature-based solutions. The nature-based solutions

protect 22,000 acres of the watershed that drains

into these reservoirs. A water ltration plant would

have cost $250 million to build and $4 million

annually to operate and maintain.

|

14

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

LAND USE PLANNING

The Land Use Element of a community’s Comprehensive

Plan (sometimes called a Master or General Plan) typically

guides land use planning. It sets goals for where and

how land will be developed and preserved over the next

20 to 30 years. It also identies strategies to support

these goals. The Land Use Element provides the basis

for the community’s land use regulations, including

zoning ordinances and subdivision and land development

ordinances (SALDOs).

ENGAGE: Planning staff typically develop the Comprehensive

Plan in coordination with other government and public

stakeholders. For coordinated investments in nature-based

solutions, planning staff should invite other departments to

help develop the Land Use Element. Include staff with roles

in parks and recreation planning, public works, environmental

protection, utilities planning, transportation planning,

oodplain management, and emergency management.

ASSESS: The land use planning process can help drive

investments in nearly every type of nature-based solution.

To prioritize nature-based solutions, consider the community’s

most pressing issues, including development or hazards and

risks. For communities approaching build-out, for example,

preserving parks and greenways before all remaining land is

developed may be most important.

Communities may choose to restore natural ecosystems like

wetlands, and reconnect natural areas. This can help native

plants and animals compete against invasive species and

resist other stressors.

UPDATE: The land use planning process should begin

with the goals and principles in the Land Use Element.

This will provide the rationale and stimulus for ordinance

improvements, policy and procedure changes, and training.

Once the Land Use Element is updated, make more

detailed updates to zoning ordinances and subdivision and

land development ordinances. Depending on the type of

nature-based solutions prioritized by the community, update

ordinances and procedures to:

•

Establish riparian buffers and protect stream corridors;

• Direct development to previously developed areas and

areas with existing infrastructure;

• Promote compact (e.g., mixed-use and transit-oriented)

development;

• Reduce impervious cover; and

• Modify landscape requirements, including tree protection

requirements.

The goal of this guide is to help communities identify and engage the staff and resources that can be

used to implement nature-based solutions to build resilience to natural hazards, which may be exacerbated

by climate change. Planning and carrying out nature-based solutions requires an integrated approach that

works across agencies and departments. This section provides tips for adding nature-based solutions to

traditional community planning processes and programs. For each program area, this section recommends

which ofcials to engage (ENGAGE); which types of nature-based solutions to consider (ASSESS); and

how to update plans, policies, and ordinances to drive those solutions (UPDATE).

Like any other project, nature-based solutions must

follow local, state, and federal regulations and

permit requirements. This usually includes environ-

mental and historic preservation (EHP) review.

Reaching out to EHP authorities early in project

design can help communities identify potential

benets and limitations of the proposed solution,

and avoid delays in implementation.

|

15

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

HAZARD MITIGATION PLANNING

Hazard mitigation activities are typically guided by a Hazard

Mitigation Plan (HMP), which is updated on a ve-year

cycle. The HMP identies specic risk reduction projects

as mitigation actions. Each action is linked to a plan that

describes how and when the project will be completed.

ENGAGE: A Steering Committee typically leads the

development of the HMP. The committee often includes

planners, emergency managers, and other local ofcials.

To enable joint investments in nature-based solutions,

invite other departments to help dene the HMP’s goals

and mitigation actions. Include staff with roles in parks

and recreation, public works, planning, environmental

protection, utilities management, and transportation

planning. They can participate in both the ve-year plan

update process and the annual reviews and updates.

ASSESS: Hazard mitigation planning can drive investments

in nearly every type of nature-based solution. To prioritize

nature-based solutions, consider the community’s most

pressing hazards. For example, addressing droughts may be

most important for communities in arid environments with high

water demand. FEMA’s Local Mitigation Planning Handbook

specically identies projects that protect natural systems as

important mitigation activities. These actions minimize losses

and preserve or restore the functions of natural systems.

UPDATE: Nature-based solutions can be integrated into HMPs

through both long-term goals and specic mitigation actions.

Mitigation actions may include nature-based projects, but they

should also promote nature-based solutions more broadly.

Consider policies and regulations, education and outreach, and

incentive-based programs. Develop these projects, policies,

and incentives with relevant departmental staff so that they

can also integrate nature-based solutions into their programs

and planning processes.

STORMWATER MANAGEMENT

Stormwater management programs typically aim to reduce

water pollution, preserve aquatic ecosystems, and protect the

public from stormwater ooding. Many must also comply with

federal and state stormwater management regulations. These

regulations are designed to reduce pollutant discharges from

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4s) and CSOs.

Communities with MS4s typically base their program on a

Stormwater Management Program Plan (SMPP). Those with

CSOs typically use a local Long-Term Control Plan (LTCP).

These plans are carried out by various local programs,

ordinances, and development procedures.

ENGAGE: Stormwater or public works departments typically

develop the SMPP or LTCP. To coordinate investments in

nature-based solutions, invite others to help develop the

plan and put it into action. Include staff with roles in parks

and recreation planning, environmental protection, utilities

planning, transportation planning, oodplain management,

and emergency management.

ASSESS: Stormwater management programs are best

suited to drive investments in neighborhood- or site-scale

nature-based solutions that retain and treat stormwater

onsite. To choose which nature-based solutions to

emphasize, consider the community’s most pressing

stormwater issues and priorities. Communities with a lot

of existing development and limited new development

might emphasize tree trenches, green roofs, and rainwater

harvesting. These nature-based practices have smaller

footprints and are easily integrated into tighter spaces.

If that community also had limited water supplies, it might

prioritize rainwater harvesting; if it did not have enough

tree cover, it might prioritize tree trenches.

UPDATE: Updating a community’s stormwater management

program should begin with its SMPP or LTCP. To encourage

the use of nature-based solutions, many communities

are adding stormwater retention standards to their

post-construction stormwater programs. According to

an EPA summary, 28 states and two territories have

post-construction retention standards. This type of standard

requires some runoff volume to be managed onsite. This

reduces both pollutant loads and erosive peak ows.

Communities can also develop a hierarchy of acceptable

nature-based solutions. For example, the Philadelphia Water

Department divides these practices into three preference

levels: Highest, Medium, and Low.

The Capital Region Council of Governments

in Connecticut established the following goal

in its 2019-2024 HMP: Increase the use of

natural, “green,” or “soft” hazard mitigation

measures such as open space preservation and

green infrastructure. Specic mitigation actions

encouraged adopting regulations to promote low

impact development and nature-based techniques.

They also supported education initiatives to help

municipal staff and elected ofcials understand

nature-based solutions practices.

|

16

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

Once the SMPP or LTCP is updated, make more detailed

updates to stormwater management ordinances and

procedures. Depending on the type of nature-based solutions

prioritized by the community, update ordinances and

procedures to:

•

Include nature-based solutions in proposed capital

projects for stormwater management for public projects;

•

Make nature-based solutions legal and preferred for

managing stormwater runoff for private projects;

•

Have stormwater management plan reviews take

place early in the development review process

for private projects;

•

Provide other ways for developers to meet stormwater

requirements when onsite alternatives are not

feasible, such as “payment-in-lieu of” programs for

private projects;

•

Emphasize collaboration between the stormwater

management department, streets department,

and private developers to build green streets;

•

Ensure that local building and plumbing codes allow

harvested rainwater for exterior and non-potable

uses; and

•

Include effective monitoring, tracking, and maintenance

requirements for stormwater management.

Rain Garden — Greenbriar Middle School in Parma, OH

|

17

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

TRANSPORTATION PLANNING

The Transportation Element of the local Comprehensive

Plan, the regional Long-Range Transportation Plan, and

the Transportation Improvement Program typically guide

transportation planning. These plans set goals for a

community’s transportation system over the next 20 to

30 years. They also identify strategies and projects to

support these goals. The plans provide the basis for local

codes related to transportation and for local investments in

transportation infrastructure.

ENGAGE: Planning staff typically develop the Comprehensive

Plan, with input from local staff and the public. To

coordinate investments in nature-based solutions, planning

staff should invite other departments to help develop the

Transportation Element. Include those with roles in parks

and recreation planning, public works, environmental

protection, utilities planning, oodplain management, and

emergency management.

ASSESS: Transportation and land use planning are closely

linked and often interdependent. As with the land use

planning process, the transportation planning process can

help drive investments in nearly every type of nature-based

solution. To prioritize nature-based solutions, consider the

community’s most pressing issues. For communities with

limited options for pedestrians, retrotting streetscapes to

increase walkability may be most important.

UPDATE: Updating the transportation planning process

should begin with the goals and principles in the

Transportation Element. These provide the rationale and

stimulus for ordinance improvements, policy and procedure

changes, and training. Once the Transportation Element

is updated, make more detailed updates to the policies,

procedures, and ordinances on street and parking design.

Communities can update their street design standards to

provide clear direction on the appropriate installation of

nature-based solutions. They can adopt a complete streets

policy that encourages designs including nature-based

solutions. And they can create a green streets manual that

provides guidance on designing nature-based solutions.

Local ordinances and procedures related to street design and

parking can also be updated. Use this process to minimize

impervious cover and promote nature-based solutions.

Depending on the type of nature-based solutions prioritized

by the community, update ordinances and procedures to

encourage or require:

•

Adding nature-based solutions to proposed transportation

projects in the Transportation Improvement Plan and

capital improvement plan;

•

Making street trees a part of public capital improvement

projects;

•

Making streets no wider than is necessary to move trafc

effectively;

•

Using pervious materials for lower-trafc paving areas,

including alleys, streets, sidewalks, driveways, and

parking lots;

•

Providing alternative parking requirements (e.g., shared

or offsite parking), and varying requirements by zone to

reect places where more trips are by foot or transit;

•

Using alternative measures to reduce required parking,

such as transportation demand management; and

•

Using nature-based solutions to strengthen the resilience

of transportation infrastructure to natural hazards.

For an excellent model of how to systematically

incorporate nature-based solutions into the

transportation planning process, communities

should review the “Eco-Logical” Approach promoted

by the Federal Highway Administration.

|

18

PLANNING AND POLICY-MAKING PHASE

OPEN SPACE PLANNING

The Open Space and Recreation Element of a community’s

Comprehensive Plan typically guides open space planning. This

element establishes a policy framework and action program.

These are used for maintaining, improving, and expanding the

community’s open space and recreational facilities.

ENGAGE: Planning staff typically develop the Comprehensive

Plan with government and public stakeholders. To

coordinate investments in nature-based solutions,

invite other departments to help develop this element.

Include staff with roles in hazard mitigation, public works,

environmental protection, utilities planning, oodplain

management, and emergency management.

ASSESS: The open space planning process can help drive

investments in nearly every type of nature-based solution. At

the watershed scale, it can support interconnected systems

of greenways and parks. These mitigate natural hazards and

provide co-benets to the community. At the neighborhood

scale, open space planning can incorporate nature-based

solutions into local parks and recreational facilities. This

helps reduce and treat neighborhood stormwater runoff. In

coastal areas, open space planning can drive investments

in living shorelines, waterfront parks, and other coastal

nature-based practices.

UPDATE: Updating the open space planning process should

begin with the Open Space and Recreation Element of the

Comprehensive Plan. Once the plan is updated, consider

more detailed updates to facilities management programs,

park planning and design, and local ordinances.

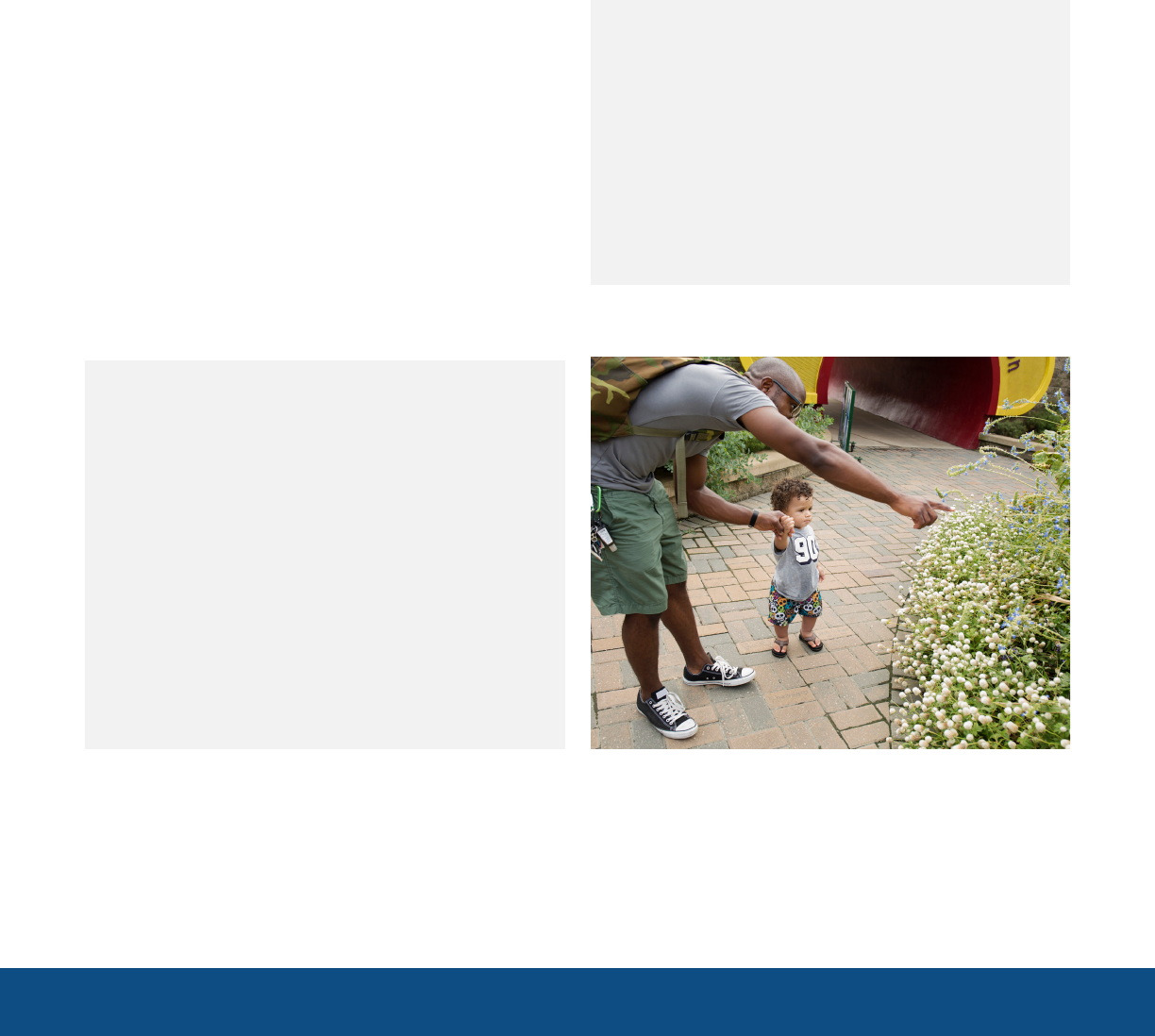

Facilities management programs can add neighborhood-scale

nature-based solutions to existing parks and playgrounds.

As local governments retrot existing facilities, they can

incorporate nature-based solutions to reduce impervious

cover, enhance tree cover, and treat and soak up stormwater

runoff. Park planning and design are also opportunities.

Communities can apply nature-based practices and principles

as they expand their network of parks and trails and design

each park site. Using nature-based solutions for retrotting

existing parks or acquiring and designing new parks can

mobilize new partners and funding sources. Finally, updating

local ordinances can help to preserve watershed-scale

nature-based solutions. Based on the needs of the

community, ordinances can be updated to:

•

Protect natural resource areas and critical habitat;

• Establish no-development buffer zones and other

protections around wetlands, riparian area, and

oodplains; and

•

Limit development and land disturbance in source water

protection areas.

FEMA’s Community Rating System (CRS) allows

participating communities to earn lower ood

insurance rates for property owners, renters,

and businesses. They get credit for actions that

reduce risk under the National Flood Insurance

Program. FEMA recently elevated the potential

CRS credit values for nature-based solutions.

Credit is given for actions such as preserving

open space, restoring wetlands, and developing

a living shoreline. The number of points awarded

for preserving open space is now among the

highest given in the program. Credits are awarded

according to the percentage of preserved open

space in a community’s oodplain. The larger

the percentage, the more credit is awarded,

accompanied by potentially higher insurance

discounts. Folly Beach, South Carolina incorporated

nature-based solutions into their CRS program and

received a 30-percent reduction in premiums.

Folly Beach, SC

|

19

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

To build a network of nature-based solutions, communities should encourage both public and private

investments. This section provides tips for boosting public investment and incentivizing private

investment. Many of these tips rely on the diverse benets of nature-based solutions. Recognizing these

diverse benets can help pool resources from public and private partners to mobilize more funding for

nature-based solutions. This section is aligned with the third goal of the National Mitigation Investment

Strategy — to make mitigation investments standard practice.

BOOSTING PUBLIC INVESTMENT

Diversifying Local Resources

Traditional local funding sources for public infrastructure include general funds, bond proceeds, taxes, and fees. Support for

nature-based solutions investments could come from taxes levied on property, special or business improvement districts, or

tax increment nancing (TIF) districts. Local fees could include development impact fees, fee-in-lieu payments, or utility fees

(including stormwater utilities). Pooling resources is also a way to integrate NBS practices into planned or ongoing capital

improvement projects. Consider NBS when creating or improving roads, streetscapes, stormwater management projects,

parks, and parking areas. Incorporating NBS into public improvements is an opportunity to lead by example and to educate

other departments, private developers, and the public.

While each funding source has pros and cons, communities should use more than one internal resource. Pooling resources is a

more cost-effective and scally responsible funding choice. Pooling resources is also a way to integrate nature-based solutions

practices into planned or ongoing capital improvement projects. Consider nature-based solutions when creating or improving

roads, streetscapes, stormwater management projects, parks, and parking areas. Incorporating nature-based solutions into

public improvements is an opportunity to lead by example and to educate other departments, private developers, and the public.

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

GENERAL FUNDS BOND PROCEEDS TAX AND FEE REVENUES

PROS

• Financial exibility

CONS

• Funds can be reassigned

• Inuenced by changes

in community, including

political climate

PROS

• Dedicated and consistent

source of funding

CONS

• Could increase local taxes

and fee rates

• Inuenced by credit rating

• Repayment often includes

interest

PROS

• Dedicated and consistent

source of funding

CONS

• Lack of nancial exibility

• Could increase local taxes

and fee rates

|

20

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

Attracting Grant Funding

To maximize public investment in nature-based solutions,

communities should creatively combine local and external

resources as often as possible. Since nature-based solutions

provide many different co-benets, a single project may

be eligible for a variety of private, state, and federal grant

programs. The key to leveraging These resources is to think

outside the box when applying for funding, and to apply to

diverse programs. For example, a coastal community may

seek grant funding for a ood risk reduction project that

uses nature-based approaches. In addition to applying for

hazard mitigation grants, this community could apply for

habitat conservation grants, water quality grants, and coastal

resilience grants. The nal section of this guide lists some

of the most common federal grant funding opportunities for

nature-based solutions. Communities should also identify

and leverage the nancial assistance available through

state-specic programs. Other potential sources are non-prot

organizations, special districts, and private foundations.

Building Nature-Based Solutions into the

Capital Improvement Plan

The Capital Improvement Plan (CIP) process is another tool

for increasing investments in nature-based solutions. Many

communities use a CIP to plan the timing and nancing of

public improvements over the medium term (approximately

ve years). Agencies submit projects to be evaluated and

included in the CIP, and the CIP team analyzes and ranks

submitted projects. Ultimately, highly ranked projects

are funded rst. Rankings often consider how the project

advances mandated activities and community priorities. They

are also based on whether the project is scally responsible.

Including a nature-based component can help increase a

project’s ranking, as nature-based solutions may contribute

toward federal Clean Water Act requirements, hazard

mitigation, and other community priorities. It is important to

emphasize the multi-functional nature of these solutions and

how they can provide more bang for the public’s buck.

Funding Nature-Based Solutions with

Stormwater Utility Fees

Stormwater utility fee programs are designed to pay for the

cost of managing stormwater runoff. Typically, stormwater

fees are collected in a fund dedicated to the stormwater

management program and stormwater-related projects.

This can be a good, steady source of funding that does

not compete with other community priorities.

Many stormwater utilities are structured to charge users

based on their property’s stormwater runoff volume.

For example, communities can charge a fee based on a

property’s impervious area, rather than its total area. For

this type of fee structure, communities need to have a

good understanding of their impervious cover. Stormwater

utilities are also able to collect fees from all property owners,

including those otherwise exempt from property taxes.

The 2017 Western Kentucky University Stormwater Utility

Survey identied 1,639 stormwater utility programs in

40 states. The smallest program served a population of 88.

As a growing suburb of Kansas City, Lenexa,

Kansas is managing the effects of increased

impervious cover through nature-based solutions.

To integrate nature-based solutions into major

capital projects, such as rebuilding roads and

parks, Lenexa is using funds from several internal

and external sources:

1. sales tax revenues;

2. stormwater utility fees;

3. new development fees; and

4. state and federal grants.

|

21

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

Financing Nature-Based Solutions with the Clean Water

State Revolving Fund

The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) is a nancial

assistance program established through the Clean Water Act.

It provides low-interest loans for water infrastructure projects

(including nature-based solutions) that address water quality.

The EPA provides funding to all 50 states and Puerto Rico

to operate CWSRF programs. States provide a 20-percent

match for all federal funds. Since the CWSRF was established,

it has supplied more than $43 billion to state programs.

With that support, states have given $133 billion in loans

to communities.

For most projects, public, private, and non-prot entities

get an average interest rate of 1.4 percent. The loan period

must not exceed 30 years. A key benet of the program’s low

interest rate is that communities may be able to cover debt

service payments without raising the rates for local taxes or

fees. By further reducing operation and maintenance costs

for infrastructure, nature-based solutions help communities

meet their loan repayment terms.

The Camden County Municipal Utility Authority

was awarded a $5.4 million loan from the New

Jersey Infrastructure Bank, the state’s CWSRF,

to fund a city-wide nature-based solutions project.

The project has an estimated cost savings of

$3.1 million over the 30-year loan. It involves

building nature-based solutions throughout the

City of Camden, including rain gardens and porous

concrete sidewalks. The project also has a green

jobs component. In the past 3 years, Camden

trained about 240 youths in nature-based

solutions maintenance.

Managed dune on Long Beach Island, NJ. Dune restoration is an

example of nature-based solutions that can be funded by many

federal funding sources.

|

22

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

INCENTIVIZING PRIVATE INVESTMENT

While public investment in nature-based solutions is critical

and continues to evolve, communities should also investigate

ways to incentivize nature-based solutions on private

property. One option is to make these investments more

appealing to homeowners, businesses, and developers.

Incentives typically use public funds to seed additional

investments by private parties. Innovative incentive-based

programs can create unique ways to fund and build

nature-based projects. Some examples are public-private

partnerships, rebates and nancing programs, grants, and

cost-share arrangements. Banking or credit trading programs,

development or redevelopment incentives, local fee or tax

discounts, and community awards and recognition programs

have also been useful. Such voluntary programs can increase

the use of nature-based solutions on private land, where

most traditional development takes place. They can balance

regulations and may relieve some of the administrative

burden that communities carry when adopting and managing

their own nature-based policies or projects.

Public-Private Partnerships

Through partnerships, local governments and private-sector

parties can invest together in public asset or service projects.

These long-term partnerships are most successful when they

have shared goals and benets. Private partners may have

more exibility than a public agency. Linking any partnership

with performance-based payments can encourage

efciencies in time and cost.

Local ofcials can work with private partners to develop and

nance nature-based solutions in many ways. One key step

is to demonstrate the benets of nature-based solutions – to

make the business case locally. Another is to offer continued

technical assistance and coordination for nature-based

projects. This may include policy support, training, or other

ways to build capacity. Finally, seek long-term agreements

with any private stakeholders that would provide these

services traditionally delivered by the public sector. Above all,

communities should create partnerships with private parties

for specic projects.

Green Certification Incentives

Certications such as LEED and SITES offer guidance

for developers to incorporate sustainability when

designing buildings and landscapes. States and

communities can provide incentives to developers to

incorporate these certications into new development

and redevelopment projects.

Rebates and Financing Programs

Rebates, tax credits, or low-interest loans can encourage

nature-based solutions and practices. For example, Tucson

Water sponsors a Rainwater Harvesting rebate program. It

provides rebates of up to $2,000 to single-family residential

or small commercial customers who install a rainwater

harvesting system. Eligible options include passive rainwater

harvesting, which directs and retains water in the landscape,

and active rainwater harvesting, such as tanks that store

water for later use. Often, participants in this kind of program

need capital at the beginning of a project. Since residents

may not want or be able to fund improvements on their

own, many communities target their rebates and loans at

businesses. Philadelphia, for example, offers low interest

(1 percent) loans for nature-based solutions retrots on

non-residential property.

Another nance option for promoting nature-based solutions

is the Department of Energy's Property Assessed Clean

Energy (PACE). Communities can use PACE to help property

owners nance nature-based solutions. It also applies to

installing renewable energy or energy-efcient assets on

private properties. Depending on state laws, communities

can create PACE programs by issuing a revenue bond to the

property owner. PACE borrowers can benet immediately

from new nature-based solutions and repay their debt by

increasing property taxes. For example, increases are at a

set rate for an agreed-upon term, typically 5–25 years. The

PACE assessment is attached as a tax on the property, not

the property owner. Because PACE is funded through private

loans or municipal bonds, it creates no liability to local

government funds.

In Prince George’s County, Maryland, a new water

resources plan proposed extensive stormwater-

related restoration. Also, 20 percent of the

county’s impervious surfaces needed to be

replaced. Recognizing its challenges in volume and

timing, the county built a public-private partnership.

A private party was contracted to restore 2,000

acres, with the potential for extending the contract

to an additional 2,000 acres if it met performance

metrics. This partnership met its project costs and

deadlines. It was also recognized for meeting social

goals such as hiring and training minority-owned

businesses and focusing on projects in

lower-income areas.

|

23

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

Grants and Cost-Share Agreements

Communities can also encourage nature-based solutions

by directly funding property owners or groups. Onondaga

County, New York has a Green Improvement Fund that

funds nature-based solutions on private commercial and

non-prot properties. Applicants in the target sewer districts

can choose their own nature-based solutions techniques,

but grants are determined by the amount of stormwater

the project captures. The Green Improvement Fund has

awarded 88 grants since 2010, for a total of nearly $11

million. Nature-based solutions projects have included the

installation of porous pavement, added green space, rain

gardens, green roofs, and inltration projects. Together, the

completed projects can capture more than 38 million gallons

of stormwater runoff per year. Philadelphia manages a similar

voluntary retrot grant program. It covers the upfront costs

of typical nature-based solutions on private property if the

owner agrees to maintain it.

Banking or Credit Trading

Banking or credit trading programs can help developers meet

onsite stormwater retention requirements when nature-based

solutions are not feasible onsite. They create a mechanism

for developers to pay the community to build nature-based

solutions off site. This concept is like that of wetland

mitigation banking.

Environmental Impact Bonds

Several traditional debt nancing tools are available to

communities. However, environmental impact bonds (EIBs)

are a recent innovation. EIBs can help communities obtain

upfront capital for hard-to-nance environmental projects.

These bonds link project performance incentives to desired

environmental outcomes. In practice, most EIBs function like

traditional bonds, with a xed interest rate and term. Unlike

normal bonds, they offer investors a “performance payment”

if projects perform better than expected. The primary benet

of this model is that it shifts the project performance risk to

a private party and ties borrowing costs to the effectiveness

of a project. If a project underperforms, investors must

reimburse the borrowing entity; if it overperforms, the entity

pays the investors. This model has potential applications for

multiple areas of environmental restoration and resilience,

including nature-based solutions.

Washington DC's Stormwater Retention Credit

(SRC) Trading program allows large-scale

development and redevelopment projects to

meet stormwater management requirements

by buying credits from properties with voluntary

nature-based solutions improvements. The credit

trading program encourages developers to choose

cost-effective, nature-based solutions. It also

creates an incentive for other property owners to

integrate green stormwater practices. Through

this program, properties that use nature-based

solutions or reduce impervious cover can earn

and sell credits to the Department of Energy

and Environment or in an open market.

Environmental Impact Bonds have already been

issued in several cities, including Washington, DC and

Atlanta, Georgia, where they are funding a range of

nature-based solutions projects to reduce stormwater

runoff and address critical ooding issues.

Modern rooftops, Brooklyn Heights, New York City

|

24

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

Development or Redevelopment Incentives

Communities can update their land use, zoning, or other

local regulations to provide incentives for using nature-based

solutions. Zoning incentives can allow a greater height,

density, or intensity of development if a developer uses

nature-based approaches. One common zoning incentive

is an increased oor-to-area ratio (FAR), which regulates