Portland State University Portland State University

PDXScholar PDXScholar

Urban Studies and Planning Faculty

Publications and Presentations

Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and

Planning

2007

Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Bleeding Albina: A History of Community

Disinvestment, 1940‐2000 Disinvestment, 1940 2000

Karen J. Gibson

Portland State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac

Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social Justice Commons, and the

Urban Studies and Planning Commons

Let us know how access to this document bene>ts you.

Citation Details Citation Details

Gibson, K. J. (2007). Bleeding Albina: A history of community disinvestment, 1940‐2000. Transforming

Anthropology, 15(1), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1525/tran.2007.15.1.03

This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and

Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us

if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected].

3

Transforming Anthropology, Vo l. 15, Numbers 1, pps 3–25. ISSN 1051-0559, electronic ISSN 1548-7466. © 2007 by the American

Anthropological Association. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through

the University of California Press’s Rights and Permissions website, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp. DOI: tran.2007.15.1.3.

3

Karen J. Gibson

BLEEDING

A

LBINA:A HISTORY OF COMMUNITY

DISINVESTMENT

, 1940–2000

Portland, Oregon, is celebrated in the planning litera-

ture as one of the nation’s most livable cities, yet there

is very little scholarship on its small Black community.

Using census data, oral histories, archival documents,

and newspaper accounts, this study analyzes residential

segregation and neighborhood disinvestment over a

60-year period. Without access to capital, housing con-

ditions worsened to the point that abandonment became

a major problem. By 1980, many of the conditions typi-

cally associated with large cities were present: high

unemployment, poor schooling, and an underground

economy that evolved into crack cocaine, gangs, and

crime. Yet some neighborhood activists argued that the

redlining, predatory lending, and housing speculation

were worse threats to community viability. In the early

1990s, the combination of low property values, renewed

access to capital, and neighborhood reinvestment

resulted in gentrification, displacement, and racial

transition. Portland is an exemplar of an urban real

estate phenomenon impacting Black communities

across the nation.

KEYWORDS: community, segregation, disinvest-

ment, gentrification, inequality

This was really part of much, much larger forces

that are at work, and they may or may not be con-

sciously malicious . . . This is the result of city pol-

icy, of other kinds of large-scale things that

systematically cripple or dismember a community.

Some neighborhoods are “fed.” Others are bled.

—Paul Bothwell, Boston Dudley Street

neighborhood activist

1

The preponderance of scholarship on Portland, Oregon,

analyzes the city’s achievements in various fields of

urban and regional planning: land use, environment,

transportation, central city revitalization, and civic

involvement (Ozawa 2004; Abbott et al. 1994). Others

debate the impact of the urban growth boundary,

designed to limit sprawling development, on housing

prices (Downs 2002; Fischel 2002; Howe 2004).

However, very little scholarship analyzes the experience

of Portland’s Black community in this relatively remote

Northwest city. Although the population is very small

(never comprising more than 7 percent of the city and

1 percent of the state), Portland provides an interesting

case study of a Black community that found itself sud-

denly in the path of urban redevelopment for “higher

and better use” after years of disinvestment. The occu-

pation of prime central city land in a region with an

urban growth boundary and in a city aggressively seek-

ing to capture population growth, coupled with an eco-

nomic boom, resulted in very rapid gentrification and

racial transition in the 1990s. As cities across the coun-

try increasingly seek to improve land values and woo the

middle and upper classes back to the central cities as an

economic development strategy, the fate of urban Black

communities is uncertain. Local policy makers are grap-

pling with ways to reduce the negative effects of sprawl-

ing development patterns, and the conversion of central

city land into residential use offers a solution, especially

as baby boomers and their children leave suburbia for

compact inner-city living. It is critical to understand the

links between the historical processes of urban develop-

ment and contemporary forces that impinge on Black

communities, so that central city residents might proac-

tively engage with these forces. This work contributes to

that effort by shedding light on the link between disin-

vestment and gentrification in Portland.

This is a case study analysis of the historical process

of segregation and neighborhood disinvestment that pre-

ceded gentrification in Portland’s Black community,

Albina. Drawing upon various sources such as census

data from 1940 to 2000, oral histories, archival docu-

ments, and news articles, it investigates the mechanisms

that facilitated residential segregation and housing disin-

vestment. It also traces some of the Black resistance

strategies to these mechanisms. Only after pressure from

Karen J. Gibson is an associate professor of urban stud-

ies and planning at Portland State University. Her

research interests concern racial economic inequality in

the urban context, housing and urban policy, and the

theory and practice of community development. She is

interested in interdisciplinary approaches to under-

standing urban life, and applied research. She holds an

M.S. in public management and policy from Carnegie

Mellon University and a Ph.D. in city and regional plan-

ning from the University of California at Berkeley.

4TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

activists and the media did politicians, seeking votes,

respond to the needs of Albina. The real estate industry

(government housing officials, Realtors, bankers,

appraisers, and landlords), by denying access to conven-

tional mortgage loans, played a pivotal role in perpetu-

ating the absentee ownership and predatory lending

practices that fueled the decline in housing conditions.

Many Black residents were denied the opportunity to

own homes when they were affordable. Even after White

flight from Albina in the 1950s and 1960s, Black home

ownership continued to be restricted by discriminatory

mortgage lending policies in the 1970s and 1980s, caus-

ing some to search elsewhere for ownership opportuni-

ties. During the 1990s, residential segregation between

Blacks and Whites in Portland decreased so sharply that

it ranked tenth nationally among metropolitan areas with

the greatest declines (Frey and Meyers 2005). Ironically,

although desegregation partly reflects the gradual open-

ing up of the housing market, it also reflects the dis-

placement of Black renters to suburban locations because

of gentrification. In 2000, the African American home

ownership rate in the city of Portland was just 38 percent,

well below the national average of 46 percent. Recently

the city, which has done a fairly good job of producing

low-income housing, began trying to remedy the racial

disparity in home ownership. While there are positive

aspects to the revitalization of Albina neighborhoods,

many Black residents wonder why it did not happen ear-

lier, when it was their community. Portland is lauded for

its livability—but livability for whom?

RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION AND HOUSING

DISINVESTMENT PROCESSES

The emergence of the black ghetto did not happen

as a chance by-product of other socioeconomic

processes. Rather, white Americans made a series

of deliberate decisions to deny blacks access to

urban housing markets and to reinforce spatial seg-

regation. Through its actions and inactions, white

America built and maintained the residential struc-

ture of the ghetto.

2

Economic disinvestment—the sustained and

systemic withdrawal of capital investment from the

built environment—is central to any explanation of

neighborhood decline.

3

This study traces the simultaneous processes of racial

residential segregation and disinvestment in Portland,

Oregon. While the scale of segregation has been very

small relative to large cities in the Midwest and

Northeast, the consequences for residents are similar.

Segregation is a tool of social and economic control that

operates by confining Black citizens to a designated

section of the city. Early sociologists labeled such areas

the “Black Belt” or the “ghetto.” Sociologist St. Clair

Drake and anthropologist Horace Cayton were prescient

in their analysis of the White rationale for segregation

in their classic study of Chicago’s South Side, Black

Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City:

Midwest Metropolis seems to say: “Negroes have a

right to live in the city, to compete for certain types of

jobs, to vote, to use public accommodations—but

they should have a community of their own. Perhaps

they should not be segregated by law, but the city

should make sure that most of them remain within a

Black Belt.” As it becomes increasingly crowded—

and “blighted”—Black Metropolis’s reputation

becomes ever more unsavory. The city assumes that

any Negroes who move anywhere will become a focal

point for another little Black Belt with a similar repu-

tation. To allow the Black Belt to disintegrate would

scatter the Negro population. To allow it to expand

will tread on the toes of vested interests, large and

small, in contiguous areas. To let it remain the same

size means the continuous worsening of slum condi-

tions there. To renovate it requires capital, but this is a

poor investment. It is better business to hold the land

for future business structures, or for the long-talked-

of rebuilding of the Black Belt as a White office-

workers’ neighborhood. The real-estate interests

consistently oppose public housing within the Black

Belt, which would drive rents down and interfere with

the ultimate plan to make the Black Belt middle-class

and White. [Drake and Cayton 1945:198, 211]

The mechanisms or “compulsions” by which cities

across the United States ensured that Black people

stayed in their place were articulated by housing scholar

and advocate Charles Abrams (1955), in Fo rbidden

Neighbors: A Study of Prejudice in Housing:

1. Physical compulsion through bombs, arson, threats,

mobs

2. Structural controls such as walls, fences, dead-end

streets

3. Social controls such as segregation in clubs, schools,

and public facilities

4. Economic compulsions such as refusal to make

mortgage loans, Realtors’ codes of ethics, and

restrictive covenants

5. Legalized compulsions that use the powers of gov-

ernment to control the movements of minorities such

as condemnation powers, urban renewal, and slum

clearance.

Various forms of these compulsions, including the physi-

cal threats such as cross-burnings, were used to restrict

Black housing choice in Portland. Rose Helper, in her

original book, Racial Policies and Practices of Real

KAREN J. GIBSON 5

Estate Brokers (1969), details how Realtors used their

“code of ethics” to put into practice the “racial real estate

ideology” that property values decline when Black people

live in White neighborhoods. This was the official word of

the American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers, which

maintained that “the clash of nationalities with dissimilar

cultures” contributed to the “destruction of value” (Helper

1969:201). Realtors, lenders, and government guarantors

widely promoted the use of restrictive covenants (mutu-

ally agreed upon by builders, Realtors, bankers, apprais-

ers, insurers, and residents) that forbade non-Whites to

own property in specific areas. Residential segregation

holds the power to mold, stigmatize, and harm the living

environment of a people. This does not imply that

“ghetto” residents are passive victims, or that they are

pathological, as some strands of urban theory suggest.

Neighborhood disinvestment involves the system-

atic withdrawal of capital (the lifeblood of the housing

market) and the neglect of public services such as

schools; building, street, and park maintenance;

garbage collection; and transportation. The classical

ecology theories of Chicago School sociology

explained neighborhood growth and decline as a natu-

ral life cycle that unfolded in stages: rural, residential

development, full occupancy, downgrading, thinning

out, and then either crash or renewal (Park et al. 1984).

Downgrading is associated with the outflow of original

residents and inflow of lower-income residents and

often corresponds with racial segregation. The housing

ages, rents fall, and often there is overcrowding that

also hastens dilapidation of the stock. Residents move

out (if they can), and the neighborhood becomes a

slum. While this interpretation is helpful for under-

standing the stages of neighborhood change, it does not

adequately explain why such changes occur, as it lacks

a discussion of capital, space, race, class, and power.

Scholars with a more critical approach analyze

neighborhood decline by emphasizing the profit-taking

of Realtors, bankers, and speculators, which systemati-

cally reduces the worth or value of housing in a process

called devalorization (N. Smith 1996). The devaloriza-

tion cycle has five stages: new housing construction and

first cycle of use, transition to landlord control, block-

busting, redlining, and abandonment. After new housing

ages, owners move elsewhere, sometimes to avoid the

cost of repair, and the neighborhood has more renters

than owners. During the second stage, absentee land-

lords may choose to profit off of the rent and decide not

to make repairs. Depending on the market, it may be

economically rational to under-maintain the property.

The transition to landlord control may or may not

include the third stage, blockbusting, but often involves

a process of racial succession, or rapid population

turnover. Blockbusting is the process by which Realtors

use the fear of racial turnover and property value decline

to induce homeowners to sell at below-market prices.

Then the Realtor sells the property at inflated prices to

Black (or other) home buyers. The fourth stage is when

banks redline the neighborhood; this reduces owner

occupancy and often prevents absentee landlords from

selling a property they no longer want to keep. At this

point, home ownership rates decline, and the downward

trajectory of dilapidation continues until the final stage:

abandonment. This is often accompanied by arson as

property owners seek to cash out through fire insurance.

Gentrification is the recycling of a neighborhood up to

the point at which property values are comparable to

those in other neighborhoods. If a developer can pur-

chase a structure in an area, rehabilitate it, make mort-

gage and interest payments, and still make a return on

the sale of the renovated building, then that area is ripe

for gentrification. The cost of mortgage money is an

important economic factor affecting the feasibility of

reinvestment. This process occurs at the level of the

neighborhood, not individual structures, and requires the

involvement of housing market actors at the institutional

scale. It also involves redlining motivated by appraisals

that devalue African American neighborhoods. When

the public and private sectors make a decision to disin-

vest, it is essentially proclaiming an area unworthy and

ensuring its decline. In this view, gentrification is not

just a matter of individual preferences for older centrally

located neighborhoods; it is a matter of financial and

governmental decisions. When capital is withheld from

certain areas, predatory lenders move in to fill the void.

Historian Kenneth Jackson (1985) described the

federal role in urban disinvestment on a mass scale

through housing and transportation policies that sup-

ported massive suburbanization after World War II.

Inner-city neighborhoods were systematically deemed

unworthy of federally insured home loans by real estate

appraisers, because they were destined for decline by

their heterogeneous populations and mixed land-use pat-

terns (residential, commercial, and industrial). When the

federal government took the lead in proclaiming older

central-city neighborhoods ineligible for investment,

local government and private sector actors followed.

Jane Jacobs (1961), a fierce critic of urban redevelop-

ment schemes, argued that the policy of denying loans to

urban neighborhoods because they were declining was a

self-fulfilling prophecy. Housing dilapidation and aban-

donment are key indicators of poverty concentration in

“underclass” neighborhoods (Jargowsky and Bane

1991). Abandonment almost always occurs simultane-

ously with tax delinquency: defraying the tax burden is

one way to milk a property (Sternlieb and Burchell

1973). Perhaps the absolute final method of cashing in

on property is through purposeful arson for insurance

6TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

payoffs. Arson was an almost nightly occurrence in the

Dudley Street neighborhood of Roxbury in Boston,

Massachusetts (Medoff and Sklar 1994).

In Portland, there is evidence supporting the notion

that housing market actors helped sections of the Albina

District reach an advanced stage of decay, making the area

ripe for reinvestment. Critical to the process was the sys-

tematic denial of mortgage capital, which was justified by

appraisals that devalued African American neighbor-

hoods. In addition, predatory lenders, speculators, and

slumlords played a strong role in keeping Albina residents

from accumulating wealth through home ownership and,

in some cases, cheated residents out of their equity invest-

ments and earnings. Since home ownership is the most

common form of wealth, this helped to perpetuate eco-

nomic inequality in Portland (Oliver and Shapiro 1997).

As the Portland economy rebounded from a reces-

sion during the early 1990s, Albina became ripe for

gentrification. Gentrification involves reinvestment in

housing and commercial buildings, as well as infra-

structural amenities such as transportation, street trees,

signage, and lighting. It includes the movement of

higher-income residents into a neighborhood and often

involves racial transition. It requires financial investment

in the built environment until property values are compa-

rable to those of other neighborhoods, and it is an insti-

tutional, rather than individual-scale, process (N. Smith

1996). In other words, it is not just a cultural or social

phenomenon reflecting a lifestyle trend—it reflects sys-

tematic reinvestment by financial institutions and the

public sector. In Portland, the Black community was

destabilized by a systematic process of private sector

disinvestment and public sector neglect. After the press

publicized the discriminatory lending practices of

Oregon bankers, the city put pressure on them to reverse

their policy. Financing became available at the same

time that the economy was improving. In addition, by

the mid-1990s, several nonprofit housing organizations

had helped to improve Albina neighborhoods by devel-

oping new housing and rehabilitating tax-foreclosed

properties. Combined with more aggressive building

code enforcement and the creation of a huge urban

renewal district and light-rail project on Interstate

Avenue, the area was primed for reinvestment. The gap

between the value of properties and what they could

potentially earn was large enough for speculators to line

up to buy tax-foreclosed properties in Albina.

THE ALBINA DISTRICT

Oregon was a Klan state—it was as prejudiced as

South Carolina, so there was very little difference

other than geographic difference.

—Otto Rutherford, community leader, 1978

We were discussing at the [Portland] Realty Board

recently the advisability of setting up certain dis-

tricts for Negroes and orientals.

—Real Estate Training Manual, 1939

4

Albina was a company town controlled by the Union

Pacific Railroad before its 1891 annexation to Portland

(MacColl 1979). This area is located within walking dis-

tance of Union Station, on the east side of the Willamette

River. Since the vast majority of Blacks, prior to World

War II, worked for the railroad as Pullman porters, those

who stayed settled near the station. Before the Great

Depression, there was a small Black community in north-

west Portland, with Black-owned businesses such as cafés,

barbershops, and the Golden West Hotel, but most did not

survive the Depression. Around 1910, they were pushed

out of that community to the east side, according to Eddie

Watson, who said, “As the town began to grow they

switched us out” (Watson 1976). Black Portlanders had

built the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church in Albina at the turn of

the century. Because they were such a tiny fraction of the

city’s population (less than 1 percent) and many lived scat-

tered about, Black Portlanders often spent time together at

church, one of the few social functions available. This

small community was well educated and primarily middle

class, and about half were homeowners. But by 1940, half

of Black Portland was confined to the Williams Avenue

area in Albina as a result of severe housing discrimination

(Pearson 1996; McElderry 2001). Residential segregation

reflected the prejudice and discrimination Black people in

Oregon had faced for more than a century, both by custom

and by law. The Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850

promised free land to White settlers only. Many of the set-

tlers preferred this territory because slavery was not per-

mitted by law, and therefore they would not face

economic competition from slaveholders. In 1857, by

popular vote, Oregon inserted an exclusion clause in the

state constitution that made it illegal for Black people to

remain in the state. This clause was not removed until

1926. Oregon was one of only six states that refused to

ratify the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution,

which gave Black people the rights of American citizen-

ship and Black men the right to vote (McLagan 1980).

The hostile racial attitude of White Oregonians man-

ifested in Portland’s built environment through real estate

practices. In 1919, the Portland Realty Board adopted a

rule declaring it unethical for an agent to sell property to

either Negro or Chinese people in a White neighborhood.

The Realtors felt that it was best to declare a section of

the city for them so that the projected decrease in prop-

erty values could be contained within limited spatial

boundaries. Historian Stuart McElderry (2001) peri-

odizes the process of “ghetto-building,” finalized by

1960, in three phases: 1910 to 1940, the 1940s, and the

KAREN J. GIBSON 7

1950s. First, between 1910 and 1940, more than half the

Black population of 1,900 was squeezed into Albina by

the real estate industry, local government, and private

landlords, who restricted housing choice to an area two

miles long and one mile wide in the Eliot neighborhood.

The second phase occurred in the 1940s, when roughly

23,000 Black workers who migrated to Portland for work

in the shipyards were restricted to segregated sections of

defense housing developments in Vanport and Guild’s

Lake and to the Eliot and Boise neighborhoods in the

Albina District. During the third phase, in the 1950s,

when defense housing was demolished by flood and

bulldozer, Blacks were funneled into the Albina District.

(Vanport, the largest wartime development in the nation,

was flooded when the dike holding back the Columbia

River broke.) As Blacks moved in, Whites moved out.

Between 1940 and 1960, the Black population in Albina

grew dramatically, while the White population shrank

significantly as more than 21,000 left for the suburbs or

other Portland neighborhoods.

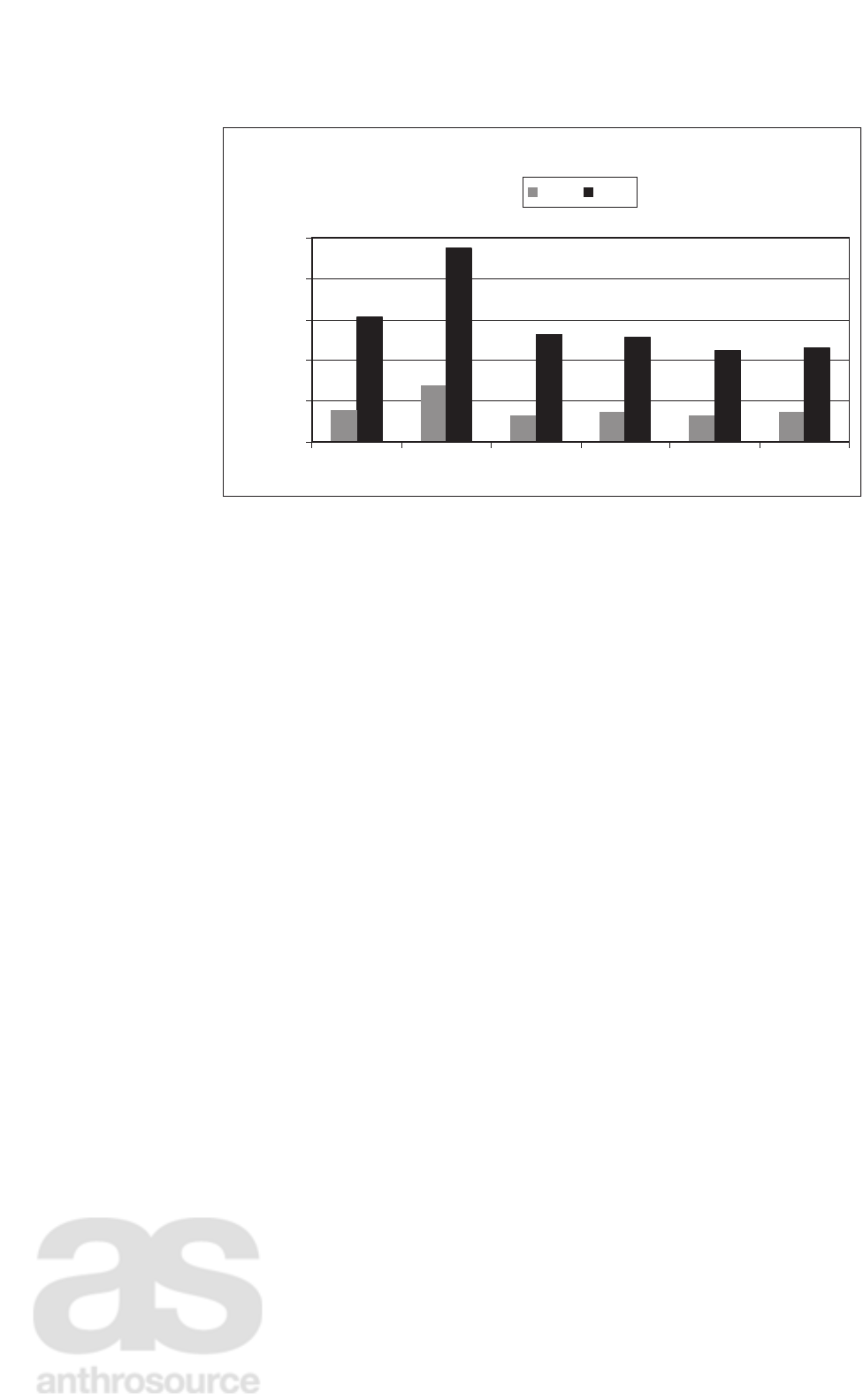

This study focuses on the neighborhoods in the

Albina District that were at least 35 percent Black in

1970 (see Figure 1). The Albina District includes all or

part of eight neighborhoods (ten census tracts) that form

Figure 1. Albina District neighborhoods in Portland, Oregon.

Lower and Upper Albina, which are distinguished both

by their location (south or north of Fremont Street) and

by the point in time that each was the center of the Black

community.

5

During the 1940s and 1950s, the Black

community was centered in Lower Albina, which con-

sists of three neighborhoods: Eliot, Irvington, and Lloyd.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, urban renewal and

freeway construction forced residents to relocate north-

ward, above Fremont Street, into Upper Albina. Upper

Albina consists of five neighborhoods: Boise, Humboldt,

King, Sabin, and Woodlawn. In the first period, the Eliot

neighborhood was the focal point; in the 1970s it was

succeeded by the King (formerly Highland) neighbor-

hood, which remains the center to this day. Table 1 shows

the point at which the Black population in each neigh-

borhood peaked, as indicated by bold print. Note that

Eliot was the largest neighborhood, both in population

and geographic area, and it therefore consists of three

census tracts. While Black residents comprised at least

43 percent of these neighborhoods at some point in the

postwar period, Portland’s Black population has never

been greater than 7 percent, and Oregon’s Black popula-

tion has never been greater than 2 percent.

Although it is helpful to distinguish Lower and

Upper Albina in order to understand the patterns of

settlement and resettlement and the changing shape of

the community, the name Albina is synonymous with the

Black community in Portland. By 1960, four of five

Black Portlanders lived in this 4.3-square-mile area, and

by 1980, despite the opening up of housing markets, one

of two still did. By 2000, slightly fewer than one of three

Black Portlanders lived there, and while many Black

Portlanders appreciate the physical improvements asso-

ciated with the recent neighborhood revitalization, they

also lament the loss of community that has come with it.

Of course it’s nice and fixed up now, and the crime

rate is down. We wouldn’t want to have it the other

way. But everyone wants home. Where is our place

then? People know where they want to live if their

culture is represented there. If a certain kind of per-

son looks at Hawthorne, they know that’s where they

can be to feel comfortable. But our culture is scat-

tered everywhere. It used to be that living “far out”

was 15th and Fremont. Now it’s 185th and Fremont.

A lot of people leave the neighborhood because they

feel they’re leaving something that’s not theirs any-

more anyway. It will never be that way again. There’s

a lot of sadness. For a lot of us, it’s just too hard to

stay and watch your history erased progressively

over time. There are just too many ghosts.

—Lisa Manning, Albina resident

6

ALBINA COMMUNITY FORMATION, 1940–1960

At that time it was almost impossible to buy property

anywhere other than around Williams Avenue . . .

Portland was really a very prejudiced city.

—Maude Young, 1976

The formation of the Black community in the Albina

District was shaped by two major events: the labor

migration during World War II and the 1948 flooding of

Vanport City, the largest single wartime development in

8T

RANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

Table 1. Black population trends in Albina District neighborhoods, 1960–2000.

Percent Black

Census Tracts 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Lower Albina

Eliot 22.01 69 50 35 38 58

22.02 72 54 43 41 25

23.01 65 77 62 58 41

Irvington 24.01 14 43 38 33 23

Lloyd 23.02 54 45 28 25 20

Upper Albina

Boise 34.02 67 84 73 70 50

Humboldt 34.01 40 65 69 69 52

King 33.01 21 61 63 63 54

King-Sabin 33.02 31 62 64 58 43

Woodlawn 36.01 12 36 49 62 51

Note: Bold figures indicate when the Black percentage peaked. Irvington refers to western half of the neighborhood. Only a

small part of Sabin is within the eastern census boundary at NE 15th Avenue, and a tiny portion of the Vernon neighborhood is

in the study area, so it is not included.

Source: Author’s calculations from United States Census Bureau Decennial Census, Summary File 3.

KAREN J. GIBSON 9

Table 2. Black population growth in west coast cities, 1940–1950.

San San

Year Los Angeles Oakland Francisco Diego Seattle Portland

1940 63,774 8,462 4,846 4,143 3,789 1,931

1950 171,209 47,562 43,502 14,904 15,666 9,529

Percent Increase 169% 462% 798% 260% 314% 394%

Source: In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528–1990. Quintard Taylor, New York:

W. W. Norton, 1998.

the United States and Oregon’s second-largest city

(Pancoast 1978). The migration, which temporarily

created a tenfold increase in the Black population dur-

ing the war years, meant that Portland had to face the

question of housing. Although city leaders stubbornly

resisted the development of any publicly subsidized

housing, defense or otherwise, the attack on Pearl

Harbor in December 1941 made it a patriotic duty to

house defense workers, at least temporarily. Within a

few months, “Magic Carpet Specials” brought the first

trainloads of roughly 23 thousand African Americans

and 100 thousand Whites, mostly from the South, to

help with the Pacific war effort. Shipyards in Portland

boomed with activity, as did five other major West

Coast cities: Seattle, San Francisco, Oakland, Los

Angeles, and San Diego. Black migrants came for the

opportunity to work, and many chose to remain after

war. The fact that more chose to leave Portland than

any other West Coast city reflected its “national repu-

tation among blacks of being the worst city on the West

Coast, as bad as any place in the South” and dismal post-

war employment prospects (Pancoast 1978:48; Taylor

1998). In Portland, after the war, there was little work, a

housing shortage, and open hostility to the newcomers

(both Black and White). The peak Black population in

1945, estimated at 23 thousand to 25 thousand, fell by

more than half by 1950. Table 2 shows that Portland’s

Black population was the smallest of the six coastal

cities, both before and after the war. Meanwhile, Los

Angeles and Seattle continued to attract migrants, and

San Diego and San Francisco saw their populations

increase modestly (Taylor 1998). A field report issued by

the National Urban League, “The West Coast and the

Negro,” predicted that after the war, the region would

have “a stranded population on its hands” because of

employment and housing discrimination, as well as resi-

dency restrictions on relief assistance (Johnson 1944:22).

Black workers faced various forms of racial dis-

crimination in both ship building (all cities except San

Diego) and aircraft production (San Diego, Los

Angeles, Seattle). In 1942, workers from New York City

protested unequal working conditions at the Kaiser

Company in Portland, claiming to have been recruited

under the “false pretense” of equal rights to jobs and

training (Pancoast 1978:41). The struggle for equal

employment opportunity in West Coast shipyards lasted

throughout the war. Black workers who refused to join

the Boilermakers’ segregated union auxiliaries were fired

by the hundreds in Portland and Los Angeles. Forming

groups such as the Shipyard Negro Organization for

Victory (with 600 members in 1943), and organizing

along with the NAACP, churches, Black newspapers, and

other local leaders, those workers pressured the Federal

Employment Practices Commission to rectify this indig-

nity. Despite their efforts, the AFL Boilermakers Union,

which covered two-thirds of all shipyard workers in the

nation (6,600 in Portland and 7,200 in Los Angeles),

never complied with the federal ruling to integrate the

union locals (A. Smith and Taylor 1980).

Vanport is now housing many of the colored peo-

ple. They will undoubtedly want to cling to those

residences until they can get something better. No

section of the city has yet been designated as a col-

ored area which might attract them from Vanport.

—W. D. B. Dodson, Chamber of Commerce, 1945

7

Housing was also a critical arena of racial conflict

all along the West Coast, and defense housing, built

with federal dollars, was little different. Black migrants

were more likely to depend on public housing than

were Whites, and “shipyard ghettos” were created in

San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Portland

(Johnson 1944; Taylor 1998:268). During the 1940s, the

Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) built and/or man-

aged more defense housing than did any other city in

the nation (18,000 units). Unlike Seattle’s housing

authority, which integrated defense housing, HAP

restricted Black families to certain developments: the vast

majority was housed in segregated sections of Vanport

(6,000 residents) and Guild’s Lake (5,000 residents), both

of which were located outside of the city’s residential

areas. Vanport was hurriedly built in 1942–43 on marsh-

land, and Guild’s Lake was built on industrial land. After

the Kaiser shipyards closed in 1945, many Black families

who could not crowd into Albina, either due to lack of

10 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

resources or the inability to find housing, remained in

Vanport and Guild’s Lake. Comprising more than one-

third of Vanport’s population, Black residents organized

the Vanport Tenants League to demand integrated housing

and fair treatment from HAP and the police (McElderry

1998). HAP and city officials were eager to dismantle the

town, calling it “troublesome” and “blighted” because of

the racially mixed population and “crackerbox” housing

construction (MacColl 1979:595). On Memorial Day

1948, a dike at the Columbia River broke and flooded

Vanport. It killed 15 people and displaced more than

5,300 families, roughly 1,000 of them Black (McElderry

1998). Yet the flood that washed away Vanport did not

solve the housing problem—it swept in the final phase of

“ghetto building” in the central city.

After this disaster, thousands of residents lived in

temporary trailers and barracks on the industrial land of

Swan Island and Guild’s Lake, some for as long as four

years. Hundreds of Black and White families were

stranded without employment or decent housing during

this time. While there was some tension between the

older Black residents and the newcomers, housing dis-

crimination affected them both. During this decade, the

pattern of racial transition in Albina neighborhoods that

would last 50 years was first established: almost in

checkerboard fashion, when Black residents settled in,

White residents would move out. This pattern repeated

itself within the eight neighborhoods of the Albina

District until the early 1990s. Between 1940 and 1950,

the entire Black population of Portland increased by

7,500 residents; about half of these crowded into the

established Black community along Williams Avenue in

Lower Albina. Whites migrated out, causing Blacks to

increase proportionately to roughly one-third of the

population. At this time, the Urban League of Portland,

an interracial social agency, became active in improving

employment and housing opportunities in Portland. In

1945, Dr. DeNorval Unthank, a physician and commu-

nity leader, provided office space for Portland’s new

Urban League branch. Bill Berry, the first executive

director, had been recruited from Chicago for a specific

purpose, according to Shelly Hill, the League’s first

employment specialist: “The president of First National

Bank, who was an Urban League member, told this new

hire, ‘We need a good intelligent Negro to tell these

people to go home.’” But Berry responded that he had

“the wrong person,” because Berry’s job was “to make

Portland a place people can stay in” (Hill 1976).

MAKING ALBINA HOME

The flood washed out segregation in housing in

Vanport. That is when the real estate board decided

that it would sell housing to Negroes only between

Oregon Street which is the Steel Bridge and

Russell from Union to the river. Later they

expanded it to Fremont so they had no choice in

buying a home; these were the only ones available.

—Shelly Hill, 1976

During the 1950s, Albina lost one-third of its popula-

tion and experienced significant racial turnover as

White residents left en masse for the suburbs and Black

residents moved into Albina from temporary war hous-

ing. By decade’s end, there were 23,000 fewer White

and 7,300 more Black residents (total population was

31,510). Lower Albina grew from one-fifth to one-half

Black, and Upper Albina increased from less than one-

20th to nearly one-third Black. As soon as it was polit-

ically feasible in the early 1950s, HAP closed the

remaining Guild’s Lake and Swan Island housing

developments, where former shipyard workers still

remained and Vanport residents had found shelter after

the flood. HAP refused to provide any public housing

alternatives, so Black residents were channeled and

compressed into Albina. Despite the protests of con-

cerned citizens, both Black and White, Portland, like

other northern cities, responded to its growing Black

population by confining them to “crowded, ancient,

unhealthy and wholly inadequate” housing (City Club

of Portland 1957:358). The City Club (a research-

based civic organization established in 1916), in its

role as a watchdog over civic issues, reflects the pro-

gressive, reformist tradition of Portland’s citizenry.

The 1957 report “The Negro in Portland: A Progress

Report, 1945–1957” documented what was generally

understood: 90 percent of Realtors would not sell a

home to a Negro in a White neighborhood. The report

drew attention to the contradiction between the Oregon

Apartment House Association’s claim that 1,000 hous-

ing vacancies existed and the “known scarcity of apart-

ment space for Negroes” (City Club of Portland

1957:361). Dr. Unthank, the only Black member of the

City Club, who 20 years earlier had protested the lack

of public housing alternatives which forced residents to

live in substandard housing, criticized the reticence of

HAP to build public housing in the face of a severe

housing shortage. But HAP and Portland Realtors, like

their national counterparts, had two major reasons for

refusing to integrate neighborhoods. First, they main-

tained that because “Negroes depress property values,”

it was unethical to sell to them in a White neighbor-

hood; and second, if they “sell to Negroes in White

areas, their business will be hurt” (City Club of

Portland 1957:359). In addition, citizens actively

sought out restrictive covenants to prevent any non-

Whites from buying homes in their neighborhoods.

City planners tended to locate urban redevelopment

KAREN J. GIBSON 11

projects in the neighborhood niches Blacks had estab-

lished for themselves, causing residents great disruption

and often relocating the same families more than once.

While racial discrimination was deeply institution-

alized in a variety of arenas, Black Portlanders had a

long history of fighting against it. After decades of

struggle, the 1950s brought success in three areas: pub-

lic accommodations, housing, and employment. Of

West Coast cities, Portland was noted for its segregated

restaurants, movie theaters, hotels, and amusement

parks. Within three blocks of the Union Station, there

were 13 signs that read “We cater to white trade only.”

Shelly Hill said, “The only way we got them down was

by threatening them” (Hill 1976). Veterans returning

from World War II broke out windows that displayed

these signs, and the Negro Taxpayers’ League organized

to boycott those who would not serve them and frequent

the places that would. The Portland branch of the

NAACP, the oldest branch on the West Coast, had

drafted the first public accommodations bill in 1919;

the bill finally passed the legislature in 1953. Otto

Rutherford, then president of the NAACP, said that

there had to be “some funerals” before the bill could

pass, meaning that members of the opposition literally

had to grow old and die before they could get the

needed votes (Tuttle 1990). Rutherford’s parents had

owned a café and barbershop in northwest Portland. He

described one of the ways Blacks got around barriers to

home ownership: since a 1926 state law said that “no

Negro or Oriental could buy property,” his “dad and

uncle had a white attorney who would buy the property

and sell it to them” (Rutherford 1978). In 1959, a Fair

Housing Law that forbade discrimination in the sale,

rental, or lease of housing passed the state legislature.

In 1961, the League of Women Voters conducted a sur-

vey in integrated neighborhoods to evaluate the appli-

cation of the Fair Housing Law. Black residents tended

to be more educated than did their White neighbors.

Four out of five said they had experienced housing dis-

crimination. One Black family claimed that the inabil-

ity to buy homes was compounded by employment

discrimination: “There is a problem of fair and adequate

employment . . . if there was adequate employment, a

Negro could purchase the kind of house he wants”

(League of Women Voters 1962).

In 1949, Oregon passed the Fair Employment

Practices Act in response to pressure from a coalition of

veterans, churches, and labor unions (Hill 1976). This

act was an improvement over a previous version of the

bill, which contained no enforcement provisions.

During the 1950s, Shelly Hill, representing the Urban

League, was instrumental in helping Blacks gain their

first employment opportunities in state and local gov-

ernment, local newspapers, private companies, “the

professions,” and local colleges. The Urban League suc-

ceeded in getting more than 180 employers to hire

Black workers. Portland’s waterfront remained segre-

gated until 1964, when the Longshoremen’s and

Warehousemen’s Union accepted Black workers

(Bosco-Milligan Foundation 1995).

Yet it was difficult for residents, regardless of race,

to save their neighborhoods from the steady march of

progress embodied in the urban renewal bulldozer. In

cities across the nation, urban power brokers, with the

help of the federal government, eagerly engaged in

central-city revitalization after World War II. Luxury

apartments, convention centers, sports arenas, hospi-

tals, universities, and freeways were the land uses that

reclaimed space occupied by relatively powerless resi-

dents in central cities, whether in immigrant White eth-

nic, Black, or skid row neighborhoods. In 1956, voters

approved the construction of the Memorial Coliseum

in the Eliot neighborhood, which destroyed commercial

establishments and 476 homes, roughly half of them

inhabited by African Americans. The Federal Aid

Highway Act of 1956 made funds available to cities

across the nation to whisk suburban residents to and

fro. As a result, several hundred housing units were

demolished in the Eliot neighborhood to make way for

Interstate 5 and Highway 99, both running north/south

through Albina. Displaced residents relocated in a

northeasterly direction, above Fremont Street and

toward Northeast 15th Avenue. Many crowded into

older housing in the Boise and Humboldt neighbor-

hoods, becoming more racially isolated from Whites.

The Housing Act of 1957 gave cities the tools they

needed to achieve the national goal of clearing slums,

and local officials used them by systematically deem-

ing Black neighborhoods “blighted” and in need of

revitalization. Thus, not long after Black Portlanders

got settled in Lower Albina, city leaders were making

plans to convert the land, which was the heart of their

community, into commercial, industrial, and institu-

tional uses. The following statement, from Portland’s

application for federal urban renewal funds, is typical

of the justifications for renewal employed by cities

across the country:

There is little doubt that the greatest concentration

of Portland’s urban blight can be found in the

Albina area encompassing the Emanuel Hospital.

This area contains the highest concentration of

low-income families and experiences the highest

incidence rate of crime in the City of Portland.

Approximately 75% to 80% of Portland’s Negro

population live within the area. The area contains

a high percentage of substandard housing and a

high rate of unemployment. Conditions will not

Figure 2. Russell and Williams Avenues, 1962. This intersection was the heart of Albina’s Black community until the city declared the area blighted

and tore it down. The block where the drug store, shops, and housing once stood now contains a patch of grass. Oregon Historical Society.

12 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

KAREN J. GIBSON 13

improve without a concerted effort by urban

renewal action. The municipal goals as established

by the Community Renewal Program for the City of

Portland further stress the urgent need to arrest the

advanced stages of blight. (Portland Development

Commission 1966:17)

Albina residents organized, seeking to remedy the

problem of aging and declining housing conditions

through rehabilitation, not clearance. While they

would have some success north of Fremont Street

through the Albina Neighborhood Improvement

Program (1961–73), Black residents would lose their

own “Main Street” at the junction of Russell and

Williams Avenues (see Figure 2).

RESHAPING THE COMMUNITY, 1960–80

When you get to feeling locked in—that’s when the

frustrations start.

—Frank Fair, Youth Worker, Church Community

Action Program, 1967 (Bosco-Milligan

Foundation 1995:95)

[Albina] could be not only one of the most accessi-

bly convenient areas of the city, but one of the most

progressive and innovative neighborhoods as well.

(City of Portland Model Cities 1969:2)

During the 1960s, Portland’s African American popula-

tion, although small relative to those in larger cities,

was experiencing the same problems associated with

racial discrimination and spatial segregation found else-

where: high unemployment and occupational segrega-

tion, poverty, overcrowded and low-quality housing,

segregated schools, and tension with police. It seems

that the relationship between the Albina community and

city agencies could be characterized by extremes of

absolute neglect and active destruction. At times when

residents resisted, they got some cooperation and support

from the city, but ultimately they could not trust that it

had their best interests at heart. Redevelopment policies

were a source of deep conflict during the 1960s and

1970s. Albina’s total population shrank by about 5,000,

and neighborhoods experienced more racial transition,

but this time most significantly in Upper Albina. Albina’s

White population dropped by nearly 8,000 residents,

three-quarters from Upper Albina, as Black residents

displaced from Lower Albina moved there. Some fled

the area because of the increased anger of Black resi-

dents, which exploded into riots in 1967 and 1969. The

Emanuel Hospital project, a classic top-down planning

effort, destroyed the heart of the Black community in

Lower Albina during the late 1960s, shifting and

expanding it toward the northeast.

More than 11 hundred housing units were lost in

Lower Albina, and the Black population in Eliot shrank

by two-thirds. Businesses along Williams Avenue such

as the Blessed Martin Day Nursery, the Chat and Chew

Restaurant, and Charlene’s Tot and Teen Shop (already

relocated from the Coliseum area) were decimated to

make way for the hospital (Bosco-Milligan Foundation

1995). By the end of the decade, the center of the Black

community was relocated to a contiguous set of neigh-

borhoods (King, Boise, and Humboldt) in an area of no

more than two and a half square miles, bounded by

Fremont and Killingsworth Avenues on the south and

north and by Mississippi and Northeast 15th Avenues

on the east and west. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard

(formerly Union Avenue) ran straight up the middle, and

the largest neighborhood, King, became the center. The

Black presence had tripled in the Irvington, King, and

Woodlawn neighborhoods, making Blacks the majority

group in Albina. The Boise neighborhood was the most

segregated: Black residents comprised 84 percent of its

population, but just 6 percent of the city’s total popula-

tion. Among the six West Coast cities, segregation

between Blacks and Whites in Portland was second only

to that in Los Angeles (Sorensen and Taeuber 1975).

Black leaders, after their experience with urban

renewal in the 1950s, devised strategies to protect, pre-

serve, and enhance their neighborhoods. In 1960,

Mayfield Webb, NAACP president and attorney, along

with clergy and other activists, resisted the Central

Albina Plan, a proposal to clear the entire area below

Fremont Street from the interstate to Martin Luther

King Jr. Boulevard (Bosco-Milligan Foundation 1995).

They secured a commitment from the city to invest in

housing and neighborhood improvements in the area

above Fremont Street, where the Black home ownership

rate was roughly 60 percent. The Albina Neighborhood

Improvement Program (ANIP) brought neighbors

together in a 35-block area, where they rehabilitated

more than 300 homes and built a park named after

Dr. Unthank (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, citizens peti-

tioned the city to extend ANIP activities below Fremont

Street and to change the city’s plan to renew the area,

but city commissioners refused. The Emanuel Hospital

project was in motion and could not be stopped. The

city expected to site a federally supported veterans’ hos-

pital there, and this justified clearance of a massive land

area (76 acres). After the heart of the Black community

was demolished, the federal project fell through, and

large swaths of land lay vacant decades after the renova-

tion of Emanuel Hospital. This was a particularly bitter

pill to swallow for those who had seen the heart of their

neighborhood destroyed. Jobs promised by the hospital

never materialized (see Figure 4). During this decade,

Eliot residents were also relocated for construction of

the school district’s central office and the city’s water

bureau. Nearly four decades later, a Black resident of

gentrified Boise claimed that “a generation of black peo-

ple” had grown up hearing the tale from their parents

and grandparents of the “wicked White people who took

away their neighborhoods” (Sanders 2005).

Urban renewal brutally disrupted various aspects

of residents’ lives: economic, social, psychological,

spiritual. It disrupted their attachment to place and

community. It forced them to start over, often without

adequate compensation for their loss. By 1969, while

middle- and working-class Blacks significantly increased

the number of homes owned in Irvington, King, Sabin,

and Woodlawn, the overall Albina home ownership rate

declined from 57 percent to 46 percent. Urban renewal

and unemployment (12 percent for males and 8 percent

for females) were key factors in the declining home

ownership rate, but the systematic refusal of banks to

14 T

RANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

Figure 3. Neighborhood clean-up by the Albina Neighborhood Improvement Project, 1961–1973 pp.

Oregon Historical Society.

16 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

provide mortgage capital was a pivotal factor. It meant

that prospective buyers could not buy and sellers could

not sell, except if they lent the money themselves. Many

in Albina, Black and White, purchased their homes “on

contract” from the sellers. A 1969 housing survey con-

cluded that “Blacks get bad terms in purchasing. They

usually buy on contract paying 10% interest. It is diffi-

cult for them to get conventional financing. Selling

prices are frequently inflated to black buyers” (Booth

1969:84). The inability to get capital to exchange

homes or invest in improvements quickened the deteri-

oration of the old, often overcrowded, housing stock. In

recognition of the problem, a Black-administered bank,

the Freedom Bank of Finance, opened in 1970.

Venerable F. Booker, the bank president, was fully

aware that the White bankers involved expected it to fail

(Laquedem 2005). At that time, the median value of

homes ($9,350) in Albina was just two-thirds the

median value in the city of Portland.

The affluence of our nation during the 1960s, the

civil rights movement, and civil unrest in urban areas

led the federal government to sponsor a variety of com-

munity development initiatives such as the War on

Poverty and Model Cities. Community action programs

during the War on Poverty were designed to give money

directly to neighborhoods that had been neglected by

local governments. In 1964, Mayfield Webb directed a

neighborhood services center funded by the War on

Poverty, and a number of community action programs

were developed in Albina at this time (Bosco-Milligan

Foundation 1995). Of course, mayors across the nation

were furious at the Johnson administration for circum-

venting their offices and empowering grassroots organ-

izations. Model Cities was the federal response to the

mayors’ complaints. It still required citizen involvement

in the form of “citizen planning boards,” but mayors

fought to retain authority over finance and projects.

While the Portland Development Commission (PDC)

had worked with Albina residents on the ANIP, it did

not involve them in its initial 1967 application and plan-

ning for $15 million in Model Cities money from the

Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD). HUD required public participation in Model

Cities, and Portland’s plan was criticized for merely

“informing” rather than “involving” residents. In a

revised plan that reached the city council in 1968, the

PDC was “shocked” at resident perceptions of the prob-

lems in their neighborhoods, especially because they

“spoke directly about racial discrimination.” By 1969,

the PDC had taken an official position opposing the

plan, in fear that the Citizens’ Planning Board would

assume the primary role in setting housing and devel-

opment policy in northeast Portland. In fact, the PDC

had kept plans for Emanuel Hospital “carefully

reserved” from the Model Cities process “despite bitter

opposition” (Abbott 1983:194–196). Charles Jordan

became the fourth director of the Model Cities program.

He later became the first Black city commissioner in

Portland. While these two federal programs “did not

solve the complex problems of Albina,” they helped

new Black leadership to emerge, and they focused

attention on the problems of Albina (Bosco-Milligan

Foundation 1995:93). However, a shortage of decent

affordable housing, residential segregation, and unem-

ployment remained vexing problems. While a variety of

community-based initiatives began during this period,

including the Albina Corporation (a job-training and

manufacturing firm), the Albina Art Center, the Albina

Yo uth Opportunity School, and the Black Educational

Center, despite these efforts, some residents lost

patience with the status quo.

Black youth in Albina, frustrated with being

“locked in” and occupied by the police, exploded in

riots in 1967 and 1969, accelerating White residential

and business flight (City of Portland Planning Bureau

1991). Riots broke out in cities across the nation in the

summer of 1967. A national commission was formed,

the Kerner Commission, which studied the reasons for

these violent explosions. The City Club of Portland

(1968) issued a report entitled “Problems of Racial

Justice in Portland” as a parallel to the national study. It

concluded the following:

The range of deficiencies and grievances in

Portland is similar to that found by the Kerner

Commission to exist in large cities in general. It

includes discrimination or inadequacies in many

areas: in police attitudes and practices; in adminis-

tration of justice; in unemployment and underem-

ployment; in consumer treatment; in education and

training; in recreation facilities and programs; in

welfare and health; in housing and community

facilities; in municipal services; in federal pro-

grams, and in the underlying attitudes and behavior

of the White community. Thus Portland shares the

common pressing problems and perils. To the

extent that its problems differ from those of Watts,

Newark, or Detroit, the differences are of degree,

not of cause and effect, or urgency. [City Club of

Portland 1968:9]

The report noted that racial residential patterns had

resulted in racially isolated schools; specifically, four

elementary schools were more than 90 percent Black

(Boise, Eliot, Humboldt, and Highland [now named

King]). Nearly half the Black children in Portland

attended these schools. The report drew on analyses of

housing conditions from Model Cities and mentioned

two key elements usually associated with a systematic

KAREN J. GIBSON 17

disinvestment process: absentee landlordism and mort-

gage redlining. These two operate in concert, as redlin-

ing prevents households from owning, and therefore

they have little choice but to rent from absentee land-

lords who often neglect the property and charge high

rent. The report also noted that substandard housing and

negative environmental health conditions were perva-

sive in Albina and that these conditions and their allevi-

ation were made more difficult by absentee ownership.

Black homeowners with equity who wanted to move out

of Albina faced discrimination in their attempts to buy

in other neighborhoods or the suburbs, and those who

stayed in the area had “more than normal difficulty in

obtaining improvement or building loans” (City Club of

Portland 1968). Speculation was noted as a problem as

well in another Model Cities study, which found that

housing investment in Albina was discouraged by the

“speculative attitude of property owners,” residents’

“poor credit,” and “builders’ fear of militant actions” as

a result of the civil unrest a few years earlier (City of

Portland Model Cities 1971:4).

The City Club’s Racial Justice Report urged the

city to “overcome deficiencies in numbers of units and

quality of available housing” and “review and reform

building and sanitary codes, and their administration

and enforcement, on an equitable, nondiscriminatory

basis” (City Club of Portland 1968:52). It noted that

Portland lagged behind other western cities with com-

parably sized Black populations in the development of

public housing. Black residents, it argued, complained

about the “scarcity” of brokers handling rental proper-

ties for African Americans. In some ways, the real estate

industry had not changed its policies from the 1940s—

many brokers continued to discriminate for fear of los-

ing “future business by dealing or listing with Negroes”

(City Club of Portland 1968: 33–36). Despite commu-

nity efforts, Albina was left to predatory lenders, spec-

ulators, and absentee landlords. The spiral of decline

began to manifest itself in the form of dilapidated and

abandoned housing, as Black residents began to relo-

cate in better housing near Albina.

During the 1970s, African Americans across the

nation saw improvements in their economic status as a

result of the civil rights movement and affirmative

action policies in education and employment. For the

first time since the post–World War II period, the trend

of Black population growth in Albina stopped as the

housing market began to open up. Economic gains were

manifested in the number of homeowners in Upper

Albina, which by 1979 exceeded the number of White

homeowners for the first time. Black residents had

taken the opportunity to buy new homes in Woodlawn,

where their home ownership rate was 56 percent, sec-

ond only to Irvington at 81 percent. Their increased

presence in Woodlawn caused many Whites to leave,

making it the last Albina neighborhood to transition to

majority Black. In Lower Albina, the reclamation of

land for commercial and industrial use meant that the

Black population in Eliot declined by 70 percent for the

second decade in a row. The only significant Black pres-

ence was on the east side of Eliot and in Irvington.

Home values in Albina remained just two-thirds of the

city’s median value, and while residents were able to

achieve the rehabilitation of several hundreds of units as

planned through the Model Cities process, this still fell

short of the need (City of Portland Planning Bureau

1977). Although a late 1970s report by the PDC stated

that the “problem of abandoned housing is a new area of

concern for the City,” the PDC would not seriously inter-

vene until the problem hit crisis proportions in the late

1980s (Portland Development Commission 1978:18).

THE ROAD TO ROCK BOTTOM, 1980–90

You’ve got to be a real strong person to live here. If

you have children, I’d advise against it.

—King resident, 1988

7

One mortgage broker, Dominion Capital, Inc., has

set up hundreds of home buyers in risky loans. The

company’s own principals said that they can make

loans because they have little competition from

conventional lenders.

8

During the 1980s, disinvestment in the Albina area con-

tinued until problems became so severe that they finally

became an issue for politicians in 1988. Economic stag-

nation, population loss, housing abandonment, crack

cocaine, gang warfare, redlining, and speculation were

all part of the scene. Neighborhood activists such as

Edna Robertson, who worked in the Model Cities pro-

gram and was the coordinator of the Northeast

Coalition of Neighborhoods, had “raised warning flags

about prostitution, drug dealing, abandoned housing

and gang activity before they became public issues”

(Oliver 1988). Gang members from the Los Angeles

area had maintained a quiet presence in Albina since the

early 1980s, but that changed during the summer of

1987, when competition intensified between the Crips

and the Bloods over crack cocaine. Dozens of dealers

from the Los Angeles area had begun streaming into

Portland in search of new markets. It helped that they

could sell crack for two to three times the price it

fetched in southern California, and that the local police

were unprepared for them (Ellis 1987).

Although 20 years earlier the City Club had criti-

cized the city for its neglect of this area, an Oregonian

journalist called Albina a “forgotten stepchild of city

18 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

planning and economic development efforts” (Durbin

1988b). Black residents who could afford to move left

the area, while those who could not stayed behind

and lived with the consequences. During the 1980s,

Irvington, King-Sabin, Humboldt, and Boise experienced

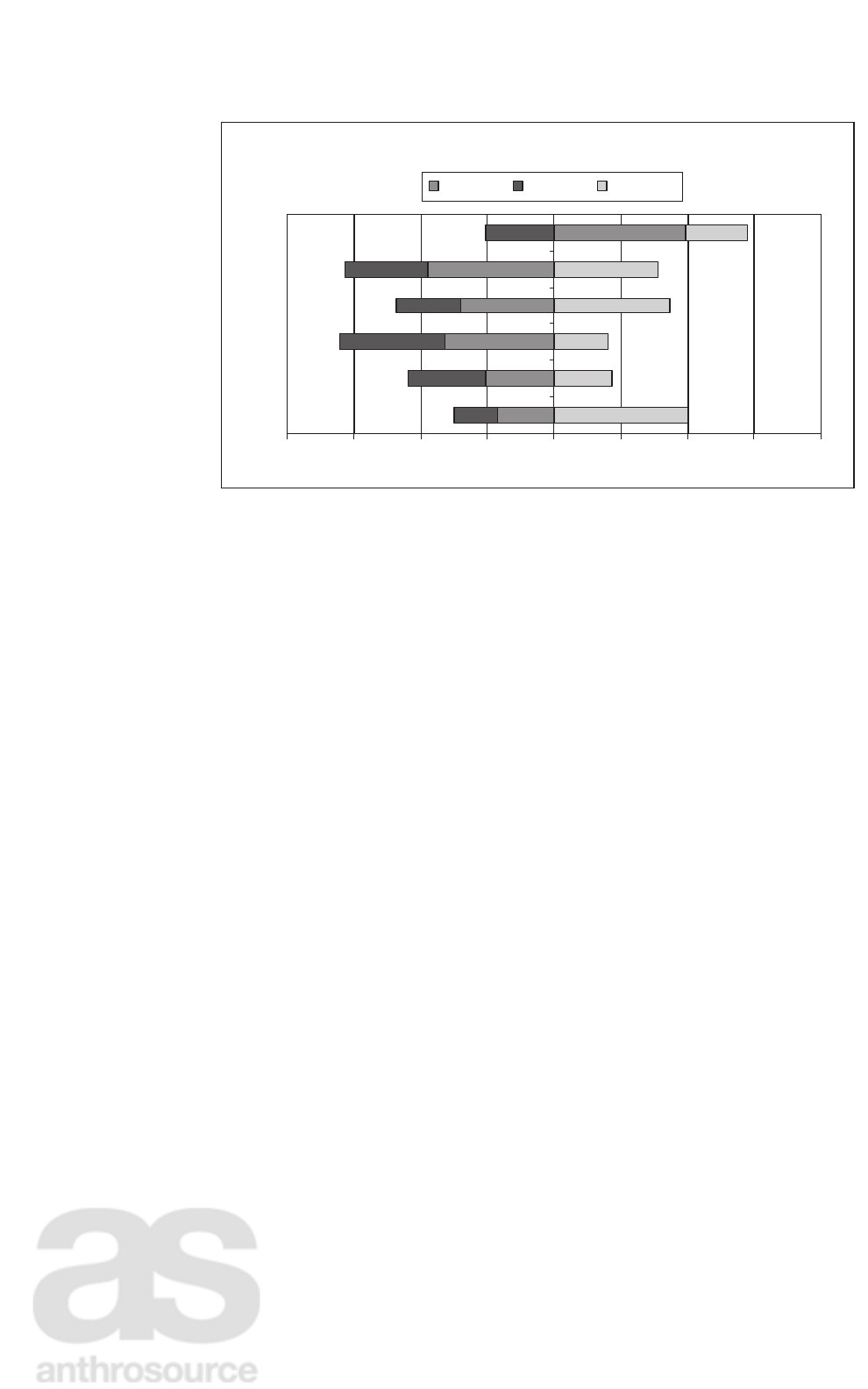

significant declines in the Black population (see Figure 5).

By the end of the decade, the proportion of Black

Portlanders in Albina had shrunk by a more than a fifth,

from 49 percent to 38 percent. The racial succession

process that began in the 1940s finally came to an end,

except in the Woodlawn neighborhood, where the Black

population increased. Woodlawn borders the northern-

most edge of the city, at the “dead end barrier” of the

Columbia floodplain (Abbott 1985:6). The long process

of moving the Black community northward, which

began around 1910, as Eddie Watson said, when they

were first “switched out” of northwest Portland, now

culminated with residents at a physical dead end.

In terms of housing and neighborhood conditions,

Albina hit rock bottom in the 1980s. The Albina popu-

lation had thinned by nearly 27 thousand people since

1950. The value of homes dropped to 58 percent of the

city’s median. In fact, the decline was so sharp that nine

neighborhoods received a special reassessment of prop-

erty; some homes sold for half their assessed value.

Absentee landlordism reached its height by 1989, when

only 44 percent of homes in Albina were owner occu-

pied. The vast majority of the change in housing occu-

pancy among Blacks in Upper Albina (96 percent) and

Lower Albina (63 percent) represented Black owners

selling homes. Some of this was due to generational

change: many of the war migrants who came in the 1940s

were now at the end of their lives, and their children had

moved on. White homeowners also left in large num-

bers, especially in Upper Albina. The decline in popula-

tion and owner occupancy can be explained by a

number of factors. Certainly the economic stagnation

that affected Albina beginning in the 1970s, and hit the

entire state hard during the 1980s, explains part of it.

The crack epidemic that devastated many communities

nationwide also hit Portland in the mid-1980s. A recov-

ering crack addict, Harrison Danley, compared the epi-

demic to the 1960s civil rights era: “We’re not burning

down houses now. We’re burning down the fabric of our

society” (Durbin 1988c). Gang shootings became more

and more frequent from the middle to late 1980s. Drug

dealing became a way for those out of work to make

quick money, and the abandoned houses provided a

place to both use and abuse. Houses would be stripped

of any valuable materials by addicts or transients in

need of money—doorknobs, light fixtures, wiring.

But the raiding of abandoned houses was only one

type of plundering going on in Albina; other forces had

been invisibly preying on the neighborhood for decades.

Back in 1968, Black homeowners had complained

about access to capital for home purchase and rehabili-

tation. In 1988, evidence of their complaints would

come to light. The King and Boise neighborhoods,

which comprised 1 percent of the city’s land, contained

26 percent of the city’s abandoned housing units. The

banking industry had left a vacuum in the community

when it decided not to lend money on properties below

$40,000. The rationale that the bank does not make

money on small loans is a poor excuse for a policy of

Figure 5. Number of people transitioning in and out of neighborhoods that

experienced higher than normal population changes.

Racial Transition in Impacted Neighborhoods, 1980s and 1990s

-1000 -750 -500 -250 0 250 500 750 1000

Eliot E

Irvington

King-Sabin

Humboldt

Boise

Woodlawn

Neighborhoods

Black 80s Black 90s

White 90s

KAREN J. GIBSON 19

blatant discrimination against Black communities

where property values are relatively low (Squires 1994).

The only kinds of sales that occurred for years in Albina

were through privately financed deals, often with terms

considered predatory. As a Boston neighborhood

activist articulated in this article’s opening quotation,

some neighborhoods are “fed,” while others are “bled”

(Medoff and Sklar 1994:33). Conventional bankers had

effectively redlined Albina—bled the life out of it. This

led to housing abandonment at a major scale. The worst

neighborhoods were Boise, Eliot, and King, with more

than 10 percent of the single-family homes vacant.

Edna Robertson said that “absentee landlords were buy-

ing up houses as tax write-offs and putting no money

into them” (Durbin 1988a). In 1988, she spent more

than three months surveying 11 neighborhoods and

counted a total of 900 abandoned buildings. This was

the final stage of the devalorization cycle.

Activists such as Ron Herndon of the Black United

Front had long urged the city to do something about ris-

ing crime and housing disinvestment, but their voices

were not heard until the 1988 mayoral campaign of Bud

Clark (Austin and Gilbert 1988). That same year, the

Portland Organizing Project, an interracial faith-based

alliance, began legal challenges against the lending

practices of local banks, using the newly fortified

Community Reinvestment Act. Eventually this issue

caught the attention of the local newspaper. In

September 1990, as a result of a three-month investiga-

tion into bank mortgage lending practices in northeast

Portland, the Oregonian published a series of articles

called “Blueprint for a Slum” (Lane and Mayes 1990).

The series documented the lack of conventional mort-

gage loans and predatory lending practices in the

Albina community. In 1987, all the banks and thrifts in

Portland made just ten mortgage loans to a four-census

tract area constituting the heart of the Albina commu-

nity. The following year, they made nine loans. This

was one-tenth the average number of loans per tract in

the metropolitan area (Lane 1990b). This explained

the flight of many Black middle-class households

from the area. It also explained why predatory lenders

and slumlords had come to fill the void left by conven-

tional lenders. Lincoln Loan and Dominion Capital

were two of the biggest companies “selling” homes to

unaware consumers, using land sales contracts that kept

real ownership in their hands. Lincoln Loan rented most

of the 200 houses it owned in Albina but sold the ones that

needed the most work to unsuspecting buyers (Mayes

1994). Lincoln Loan not only lent money to buy homes

but also lent homeowners money to fix up the homes.

When the owners wanted to cash out and move on, they

would find out that they didn’t really own the house after

all. Dominion Capital owned more than 350 houses in

inner northeast Portland and “sold” them to buyers,

sometimes even when previous investors still had title.

The scam worked as follows: Dominion would buy

property at low prices, get phony appraisals that over-

valued the property, and entice buyers into sales con-

tracts with high-interest mortgage loans containing a

balloon payment clause, which required that the mort-

gage be paid in full after a short period. Unsuspecting

buyers who were unable to meet the balloon payment

would be evicted. Dominion would then find another

family to swindle. Shortly after “Blueprint for a Slum”

ran in the paper, the state attorney general investigated

Dominion, and the owners (one was named Cyril Worm)

were sentenced to prison on 32 counts of fraud and rack-

eteering. Albina had become a host for predators

because of the void in conventional mortgage lending.

Many neighborhood activists felt that these people had

done more to hasten the deterioration of Albina than the

crack dealers and gangbangers. Herndon, lamenting the

decline in neighborhood stability that resulted from the

departure of the Black middle class, pointed to the

bankers: “Had they insisted that fairness be exercised—

almost single-handedly they could have stabilized that

community a long time ago” (Lane 1990b). Yet the state

had also failed to protect its consumers.

RECLAMATION AND TRANSFORMATION,

1990–2000

I can guarantee you they are paying more in rent

than they would to buy a house in this neighborhood.

—Ora Hart, Realtor

9

We fought like mad people to keep crime out of

here. Had we not fought, I don’t know what this area

would’ve eventually been. But the newcomers

haven’t given us credit for it. I envisioned cleaning

up the neighborhood, making the neighborhood liv-

able for all of us. . . . We never envisioned that the

government would move in and mainly assist

Whites. They came in to the area, younger Whites.

[The Portland Development Commission] gave

them business and home loans and grants, and made

it comfortable and easy for them to come. I didn’t

envision that those young people would come in

with what I perceive as an attitude. They didn’t come

in “We want to be a part of you.” They came in with

the idea, “We’re here and we’re in charge.” . . . In the

past, Blacks and Whites worked very strongly

together. We were one. This thing that happened in