i

The Cinderella Tale: Oral, Literary, and Film Traditions

By

Olivia Camille Williams

An Honors Thesis

Submitted to the Faculty of

Mississippi State University

Mississippi State, Mississippi

April 2019

iii

Abstract

Folk and fairy tales have been told for centuries. The most prevalent medium of

dispersing popular tales changed with technological advancements. Printed word

superseded oral storytelling, to be succeeded by film. Some communal aspects of the

tales were lost as print emerged, but with print came illustrations to describe the text.

Film reimbued the tales with some of the theatrical elements of the oral tale while

keeping, and heightening, the visual elements of the illustrated texts. The tale Cinderella

has been, and still is, remarkably poplar. As such, it has received attention in academic

circles and popular culture. The tale, due to the many variants, is difficult to define, but

there are some core elements that seem to allow broad generalizations. Tales like

Cinderella, having survived centuries, speak to deeply-seated human desires to commune

with others, to tell stories, to tell truths.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................... i

APPROVAL PAGE ........................................................................................................................ ii

ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... iv

LIST OF TABLES ...........................................................................................................................v

INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1

The Fairy Tale ..............................................................................................................................1

A Brief Analysis of Cinderella .....................................................................................................2

THE CHANGING MEDIUM OF FAIRY TALES .........................................................................6

Oral Traditions .............................................................................................................................6

Literary Traditions ........................................................................................................................7

Film Traditions ...........................................................................................................................12

ELEMENTS OF THE CINDERELLA STORY............................................................................16

Professional Scholarship ............................................................................................................17

Path to the United States ............................................................................................................19

Popular Culture ..........................................................................................................................20

Social Implications .....................................................................................................................22

CONCLUSION ..............................................................................................................................29

REFERENCES ..............................................................................................................................31

APPENDIX ....................................................................................................................................35

A Aschenputtel ......................................................................................................................35

B Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre .........................................................................44

C Propp morphology .............................................................................................................51

v

List of Tables

1 Comparison between Cox, Rooth, Aarne-Thompson systems ..........................................18

2 Ashenputtel actions as phases of human life cycle ............................................................26

C1 The 31-function plot structure of Charles Perrault’s Cinderella .......................................51

C2 The cast of characters in Perrault’s Cinderella ..................................................................53

C3 The 31-function plot genotype of Ashenputtel...................................................................54

C4 The cast of characters in Aschenputtel ...............................................................................59

1

Introduction

Telling folk tales, proverbs, jokes—singing songs, dancing—these activities allow for the

preservation and transmission of tradition, of cultural values, forming intellectual and emotional

ties between those within a culture. Thus, tales are a part of the collective human experience.

They are easily accessible, fluid, and allow for commentary on social features within a culture. A

culture is “not a fixed, unified, or clearly bounded whole, but rather is part of an ongoing process

of revision and negotiation” (Senehi, 2009, p. xlviii). The fluidity within a culture is reflected in

the tales that are told. Tellers of tales alter their stories when social norms change; their

audiences require it.

If a particular text appears continually in a cultural tradition, surviving changes within

that cultural tradition, the text ought to show something of that culture’s preoccupations.

Nonetheless, meanings of texts are often abstract; nuances within texts can be interpreted

differently by the listener or reader, based on his or her background knowledge and life

experiences. Furthermore, a variety of interpretations are open to texts, since they are multivocal

in nature. “Even a performer’s own discussion of her work can be disputed as reflecting

historical and cultural ideology in ways in which the creator is unaware. Culture is a dynamic

negotiation of meaning” (Senehi, 2009, p. lvii). In this manner, a tale may be said to have

multiple meanings, dependent on both audience and performer.

The Fairy Tale

Myths, fables, folk and fairy tales reflect aspects of the human condition; there may be

elements that are personal, unique to a specific people group, as wells as universal elements,

relevant to the whole of humanity. Elements of enchantment have been incorporated into stories

through words and imagery; these stories have been shared with children, grandchildren, and

2

neighbors for ages. These tales were spread orally for thousands of years before being

recorded—first in print, and then on film reels. Those who recorded the stories wanted to

preserve life experiences that were culturally significant. Biechonski’s (2005) definition may be

used to provide greater understanding of the components of folk and fairy tales. By this

definition, a folk story is:

a narrative, usually created anonymously, which is told and retold orally from one group

to another across generations and centuries, a form of education, entertainment, and

history, a lesson in morality, cultural values and social requirements, and lastly, a story

which addresses current issues as each teller revises the story, making it relevant to the

audience and time/place in which it is told. (p. 95)

This definition provides a greater understanding of the components of a fairy tale. This definition

notes the necessity of noting cultural and social ideologies when discussing fairy tales.

“Fairytales, like all forms of human creative expression, are surely worthy of thoughtful

reflection” (Dundes, 1986, p. xvii). Often, fairy tales are assumed to belong to the nursery. But

the tales’ power extends far past a child’s entertainment. Sometimes, fairy tales connote

hopelessly unrealistic, romantic ideals. Fairy tales are far more realistic, harsh, uncompromising

than that. They are human creations, and as such show the usage of humans, show the realities of

human existence.

A Brief Analysis of Cinderella

Cinderella is a fairy tale that has shown an extraordinary endurance. “No other single tale

is more beloved in the Western world, and it is likely that its special place in the hearts and

minds of women and men will continue for generations to come” (Dundes, 1986, p. xvii). For

what reasons has this tale endured through time, resisting cultural transformation? Many believe

3

the symbolism in tales, shared through common archetypes, endear fairy tales to their audiences.

Carl Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz discussed images and symbols within stories as

archetypes. These archetypes have existed within the human collective unconscious, as symbols

for the experiences of mankind and for human characteristics (Adler & Hull, 1980). Several

archetypes are present in this beloved fairy tale.

Cinderella herself is one archetype; she may be considered a persecuted heroine. The evil

stepmother is another archetype. The stepmother character is prevalent in fairy tales. The

audience assumes, when encountering this stepparent, that she will be evil, cruel, even abusive.

Her treatment of the heroine is never accidental or careless; the evil stepmother consciously

chooses to promote another child or children over Cinderella. Cinderella’s prince, too, may be

described as an archetype. He is struck by the beauty of the girl he dances with; to her that can fit

the shoe, he troths his love, his hand. Listed are just three of the many archetypes to be found in

the Cinderella tale.

Cinderella has provided imagery and allegory pertaining to women and family. To some

readers, Cinderella is:

grey and dark and dull, is all neglected when she is away from the Sun, obscured by the

envious Clouds, her sisters, and by her stepmother, the Night…she is Aurora, the Dawn,

and the fairy Prince is the Morning Sun, ever pursuing her to claim her for his bride.

(Ralston, 1982, p. 50)

To other readers, Cinderella’s story parallels the story of Christ:

[the Prince must plight] himself to her while she is a kitchen maid, or the spell can never

be broken…The man of perfect heart, living in the guise of a poor carpenter’s son, has to

be accepted in his lowly state…if his mission was to be a success…God the Father [could

4

not] assist him with a direct sign. Had Christ been shown in his full glory, recognition of

his virtues whether by pauper or by prince, would have been valueless. (Opie & Opie,

1992, p. 14)

To yet other readers, the little ash girl is understood to represent Death:

Something in man was bound to struggle against this subjugation [to the immutable law

of death], for it is only with extreme unwillingness that he gives up his claim to an

exceptional position. Man, as we know, makes use of his imaginative activity in order to

satisfy the wishes that reality does not satisfy…The third of the sisters was no longer

Death; she was the fairest, best, most desirable and most loveable of women. (Freud,

1958, p. 299)

Many scholars have related the cinders, the ash, that covers Cinderella with Ash Wednesday or

mourning rituals, for Cinderella mourns for her mother (Warner, 1994). Additionally, Cinderella

is associated with the home and hearth; in that, she bears resemblance to the Greek goddess

Hestia (Yearley, 1924).

These and other interpretations, attached to literary works by academics and the

populace, comprise a vast body of work. The literary works themselves are diverse and

multitudinous. To that number must be added numerous film adaptations, as well as the

marketing and advertising related to the releases. Altogether, Cinderella is a massive

conglomerate, a formidable presence.

Modern adaptations of Cinderella show a marked debt to both oral and literary traditions.

This paper will trace the history of folklore, of fairy tales and briefly touch on historical

instances and figures that affected the genre. Additionally, the form and transmission of the

Cinderella story will be expanded upon. However, Cinderella is hard to define; the elements that

5

determine if a tale can be called Cinderella, the elements that constitute this tale type, are fluid.

These elements will also be discussed.

Any film adaptation is a synthesis of multiple sources, a commentary on contemporary

culture. After release, as the film enters the popular imagination, commentaries and adaptations

will appear. The most visible, pervasive film fairy tales are products of the Disney Corporation.

Since these films are visible across the globe—and very prevalent in the country of Walt

Disney’s birth—these are the main film versions that will be touched upon in this paper.

6

The Changing Medium of Fairy Tales

Folk and fairy tales have traditionally been used to pass knowledge of experiences from

an older teller to a younger audience. Warner (1994) noted:

They present pictures of perils and possibilities that lie ahead, they use terror to set limits

on choice and offer consolation to the wronged, they draw social outlines around girls

and boys, fathers and mothers, the rich and the poor, the rulers and the ruled, they point

out the evildoers and garland the virtuous, they stand up to adversity with dreams of

vengeance, power and vindication. (p. 21)

This younger audience, grown, passes these tales—the pictures of life and society—to the next

generation. Folk tales are generally oral, fairy tales literary. But oral tales, when existing near

literary, both influence and are influenced by literary texts. Furthermore, no author used the term

‘fairy tale’ until Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy coined it in 1697, when she published her first

collection of tales. She called her stories contes des fées, literally tales about fairies. In 1707, her

collection was published in English and called Tales of the Fairies. But the term fairy tale did

not become common until around 1750 (Zipes, 2012). Fairy tales were not originally intended

for children, nor were they originally written works: thus, it would then be absurd to date the

origin of the literary fairy tale to Perrault (Zipes, 1994). Fairy tales are dependent on an older,

oral tradition; the history of the fairy tale is connected to the history of the folk tale.

Oral Traditions

The telling of folk tales in peasant communities was a communal activity. In French

peasant communities, as daylight faded, velées—hearthside sessions—offered a space for men

and women to talk and to preach and to teach; these events occurred at the same time as domestic

tasks like spinning, or the preparation of foodstuffs for pickling and storage (Warner, 1994). In

7

this environment, stories were often told. Professional storytellers would move from community

to community telling tales. These storytellers interacted with an audience who often asked

questions and suggested changes, an audience who actively participated in the event. This served

to limit the creativity of the narrator, for he required some measure of community approval

(Oring, 1986). In this context, the tales gave vent to frustrations felt by commoners and were

reflective of actual and possible behavior, strengthening social bonds. Most motifs can be traced

back to rituals, habits, customs, or laws of pre-capitalist societies; these motifs were inextricably

tied to the social situation of agrarian lower classes (Zipes, 1979). Children of the elite, though,

often heard the same stories from governesses and nurses charged with their care.

Those studying non-western oral folk tales have an advantage; in Europe, written and oral

tale versions existed side by side for more than a century (Dundes, 1986). However, chapbooks,

or cheap books, challenge the supposed orality of the folk tale genre, at least in Western Europe.

They circulated throughout the nineteenth century, crossing national borders and geographic

boundaries (Sumpter, 2008). Bibliothéque Bleue, carried by colporteaurs or peddlers throughout

France, held shortened versions of literary tales; this material reentered oral traditions and

sometimes found its way back to literate writers (Zipes, 1994). European oral tales informed and

were informed by literary traditions.

Literary Traditions

The beginning of the fairy tale genre, a literary genre, began in France in the seventeenth

century (Zipes, 1979). The genre is often associated with aristocratic women. These women

developed it “as a type of parlor game,” wherein women could demonstrate their “intelligence

and education through different types of conversational games” (Zipes, 1994, p. 21). The

8

Marquise de Rambouillet (née Catherine de Vivonne de Savelin, 1588-1665) began receiving

guests at her home, instead of at the court of Louis XIII:

She invited her guests to attend her in her chamber bleue, her blue bedroom…In this

‘alternative court’ the lady lay in bed, on her lit de parade (her show bed) in her alcove,

waiting to be amused and provoked, to be told stories, real and imaginary, to exchange

news, to argue and theorize, speculate and plot. The Marquise de Rambouillet sat her

favorite guests down to talk to her by her side in the ruelle—the ‘alley’—which was the

space between her bed and the wall. (Warner, 1994, p. 50).

Most modern favorites were products of ruelles (Warner, 1994). In this setting, and in

other salons and courts, tales could be told bagatelle, that is, the teller would tell a tale based on

a specific motif, to be judged. Another member of the group would follow, telling a tale, “not in

direct competition with the other teller, but in order to continue the game and vary the

possibilities for linguistic expression” (Zipes, 1994, p. 21). By the 1690s the salon fairy tale

became so acceptable that women and men began writing their tales down to publish them. The

genre was then institutionalized as a description of proper modes of behavior in different

situations, though it also “mapped out narrative strategies for literary socialization,” and

sometimes was a symbolical gesture “of subversion to question the ruling standards of taste and

behaviors” (Zipes, 1994, p. 11).

Publications of tales surfaced in other countries, though with completely different intent

than the French authors. Many authors sought to gather, transcribe, and print collections of tales

to establish authentic versions (Zipes, 1979). The writers that became the most popular self-

censored their works, expunging it of vulgarities (Zipes, 1994). Didactic intentions began to

exert a stronger influence on fairy tales after the eighteenth century; the Brothers Grimm led the

9

way in this endeavor, as they re-edited and reshaped successive editions of their Kinder und

Hausmärchen to improve the message (Warner, 1994).

The Brothers Grimm thought the stories they collected were “innocent expressions and

representations of the divine nature of the world.” The tales—“pristine,” “culturally and

historically profound”—needed to be “conserved and disseminated before the tales vanished”

(Zipes, 2015, p. 206). The Grimms believed the tales helped people to commune with themselves

and the world at large, fostering hope. To them, fairy tales “served as moral correctives to an

unjust world and revealed truths about human experience through exquisite metaphor” (Zipes,

2015, p. 206).

The Grimms believed the most natural and pure forms of culture—that which held a

community together—were linguistic and located in the past. By 1809, they had amassed a large

number of wonder tales, legends, anecdotes, and other documents. They sent the collection to

Clemens Brentano. Achim von Arim, a friend of Brentano, encouraged the brothers to publish

their collection because he suspected Brentano would never use the tales. The first volume came

out in 1812 but was not well received by friends or critics. The Grimms were again disappointed

by the critical reception when the second volume was published in 1815. By 1819, they released

a second edition in which they strove to make the tales more accessible to the general public.

There were 156 tales in the first edition, 170 tales in the second. Scholarly notes were removed

in 1822. In all editions, the tales were heavily edited, mostly by Wilhelm. Changes were made to

avoid “indecent scenes;” tales that might cause offence were eliminated, and the tales were

stylized “to evoke their folk poetry and original virtue” (Zipes, 2015, p. 207).

Victorian England was no less absorbed than Germany with fairy tales. Sixpenny and

shilling novelettes and circulating-libraries enabled the circulation of gothic fiction novels. The

10

advent of cheap magazines increased the visibility of fairy tales, for chapbooks no longer existed

(Sumpter, 2008). Andrew Lang’s books or other titles marketed to the middle class—sometimes

classified as Victorian classics—were too expensive for everyone. Penny publications made

stories the “privilege of the poor” rather than the “prerequisite of the rich” (Sumpter, 2008, p.

32). Though many chose to tout fairy tales as stories within which universalities were expressed,

class distinctions were evident in circulation modes. Working-class readerships of periodicals

and newspapers often helped to secure the reputation of a writer, since both formats printed

reviews as well as the tales themselves (Sumpter, 2008).

The popularity of Perrault’s shorter, planer versions over his contemporaries is partially

accounted or by the fact that the tales began to be specifically marketed to children. (Benson,

2003). Through this process, the form and structure of the tales came to be regulated to protect

young minds. Some writers, like Hans Christian Anderson, specifically wrote their tales for

children, rather than editing and sanitizing pre-existing tales (Schenda, 1986). The tales were

intended to teach codes of civility. They also reinforced the existing social and power structures.

The tales, too, were shortened to accommodate a younger audience (Zipes, 1994).

Mme le Prince de Beaumont “pioneered the use of the fairytale form to mould the young”

(Warner, 1994, p. 297). She was born in Rouen and was unhappily married. She emigrated to

the England around 1745 and became a governess. Beaumont “wrote out of deep involvement

with the young, genuinely seeking to engage the minds of her pupils, and doing so intelligently

and not too earnestly” (Opie & Opie, 1992, p. 25). Her Magasin des enfans, ou dialogues entre

une sage Gouvernante et plusieurs de ses Élèves was translated as The Young Misses Magazine

in 1761. In it “the useful was blended throughout with the agreimmanent

11

eable.” It was “written in a plain colloquial style,” one that had not often been used

“when addressing young misses of ten and twelve years old” (Opie & Opie, 1992, p. 25).

Integral to any discussion of fairy tales in Victorian England are illustrators and

illustrations. Images were usually in conformity with the text, in a subservient role to the text

(Zipes, 1994). But a few illustrators like Gustav Doré, George Cruikshank, Walter Crane,

Charles Folkard, and Arthur Rackham showed great ingenuity in interpreting fairy tales.

Sixpenny juvenile monthlies tended to employ eminent illustrators and showed extensive

leanings toward fantasy and natural history, though fantasy appeared in shilling monthlies for

adults as well. Editors of these monthlies did not “regard fairy tales as children’s literature, but as

relics that offered insights into cultural origins—insights into the ‘childhood’ of the race.” These

types of literature show the movement away from “the child as exemplar of original sin towards

a notion of childhood as a state of imaginative purity,” and, as such, show “an obvious debt to a

Romantic legacy” (Sumpter, 2008, p. 39).

The periodical culture helped to reinvent the fairy tale. The press perpetuated the idea

that the origin of fairy tales was “ancient, communal and oral” (Sumpter, 2008, p. 177). By the

end of the nineteenth century, the fairy tale existed in high art forms like operas and ballets as

well as in low art forms such as folk plays, vaudevilles, and parodies (Zipes, 1994). But print

was the main carrier of the tales, preserving fairy tales through generations and social upheavals.

“All readers of Jane Eyre or Great Expectations [will] know [that] fairy and fairy-tale

motifs were not confined to Victorian fantasy. They were appropriated in realist novels, in ballet

and pantomime, and in poetry and painting” (Sumpter, 2008, p. 5). Fairy tales existed in forms

intended for an adult audience as well as forms intended for children. Various schools of literary

12

criticism that dealt with folk and fairy tales were institutionalized by the end of the century

(Zipes, 1994).

People have been lamenting the death of fairies by print since Chaucer’s time. “Perhaps

the press became such a potent symbol of [fairies’] decline because it was intimately linked to

other developments frequently associated with the fairies’ exile: mass education, the

popularization of science, urbanization and industrialization” (Sumpter, 2008, p. 9). But print

could not, and did not, eradicate the tales. It preserved the tales and allowed for experiementation

with word and image.

Another medium grew to overshadow print. This medium ensured the place fairy and folk

tales hold in modern popular culture.

Film Traditions

The application of the moving picture to fairy tales drastically altered the appearance of

the tales. Broadside, broadsheet or image d’Epinal in Europe and America were the forerunners

to the comic book; they anticipated the first animated cartoons (Zipes, 1994). Many

innovations—photography (1839), telegraph (1844), telephone (1876), phonograph (1877),

motion picture (1891), radio (1906), television (1923), sound motion picture (1927)—have

affected the transmission and reception of fairy tales (Zipes, 1979). Presently, film fairy tales

dominate over any other form of transmission. The man most recognizably attached to this

phenomenon must be Walt Disney. Disney identified closely with fairy tales; “it is no wonder his

name virtually became synonymous with the genre of the fairy tale itself” (Zipes, 1994, p. 76).

He sources the stories for his animated films from European folklorists and storytellers—

storytellers like Aesop, Grimm, Perrault, Anderson (Allan, 1999). Though the tales did not

13

originate with Disney—or with any one man—his aptitude as a storyteller, artist, and

businessman cemented his place in the American cultural arena.

Disney was not the first to use fantasy and fairy tale motifs in film. In advertisements and

commercials, fairy tale motifs were ubiquitous—as they still are. Georges Méliès began

experimenting with fairy tale motifs as early as 1896 in his trick films, though he illustrated

rather than re-created the tales. Cinema, however, was still in early phase of development, so

Méliès can hardly be credited with the cinematic institutionalization of the genre. With

technological progression, “a new way of making moving pictures” was invented. “Scenes could

now be staged and selected especially for the camera, and the movie maker could control both

the material and its arrangement” (Zipes, 1994, p. 76).

The first feature length film fairy tale was a Disney creation: Snow White and the Seven

Dwarves. In the 1930s, standard techniques and styles were established by the Disney studio.

“Everything that has happed in animation since has either grown out of that work or been a

conscious reaction against it” (White, 1992, p. 12).

Disney made several Laugh-O-Gram fairy tale films. He moved to Hollywood in 1923;

that year, he produced Alice’s Wonderland, a film about a girl—named Alice—visiting an

animation studio. The film combined live action and animation. A total of 56 Alice films were

produced between 1923 and 1927, with multiple girls playing the role of Alice. By 1927, Alice

was no longer popular; Disney and Ub Iwerks developed Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Mintz, who

owned the copyright to Oswald, lured some of Disney’s best animators to work for another

studio in February of 1928. In 1928, Steamboat Willie, with Mickey Mouse, was released; it was

the first animated cartoon with sound. “Disney became known for introducing all kinds of new

innovations and improving animation so that animated films became almost as realistic as films

14

with live actors and natural settings” (Zipes, 1994, p. 85). With all of the improvements and

innovation, animated fairy tales became “a vehicle for animators to express their artistic talents

and develop technology” (Zipes, 1994, p. 80).

Snow White was conceived of in 1934 and took three years to complete. It was greeted

with popular and critical acclaim. The Disney cartoons were praised for the craftmanship. It was

“argued that the formal elements of sound and color had been used more successfully in the

cartoons of Disney and the Fleischer studio than they had in live-action feature films,” reaching

the point that “photographed and dramatic moving picture should be tending, in

which…everything possible is expressed in movement and the sound is used for support and

clarification and for contrast” (White, 1992, p. 5). The fairy tale genre changed dramatically

following the release of Snow White. Film became an indispensable story telling tool and

“Disney became the orchestrator of a corporate network that changed the function of the fairy-

tale genre in America” (Zipes, 1994, p. 94).

Following the success of Snow White, several other feature length animations were made.

Their reception, however, was only lukewarm. In the 1940s, critics reassessed Disney’s

animation and praise was not as positive as it had been (Schenda, 1986). Cinderella was released

in 1950; it proved to be Disney’s next popular hit. Nonetheless, critical acclaim fell as popularity

rose (White, 1992). Many comparisons have been made between Disney’s “wry, irreverent tone”

in Kansas City and the tone taken when the studio begins to dominate the American

entertainment industry (Zipes, 1994, p. 94). Critics argued that banal consumerism had

overwritten the early experimentation and the avant-garde tendencies, ignoring the fact that “it is

one thing for a cartoon to be abstract, experimental, and deftly allusive for seven minutes; it is

15

quite another thing to do it for ninety minutes” (White, 1992, p. 7). Recently, live action remakes

of Disney’s animated classics have added yet another dimension to fairy tales in popular culture.

The change in medium from text to film reimbued the fairy tale with some of the

characteristics of the performed oral tale; the voice, the movement have been restored. But there

are drawbacks in this shift of medium: whereas the “the oral excites visualization, giving the

imagination semi-free play,” the “visual becomes literal, imprinting the imagination and the

heroine” The “dominance of imagery over word in storytelling today has pushed verbal agility

into the background” (Warner, 1994, p. 270).

16

The Elements of the Cinderella Story

There exist over seven-hundred variants of the tale type that can be loosely categorized as

Cinderella (Mei, 1990). The oldest datable version is called Yeh-hsein. It was collected by a man

named Tuan Ch’êng-shih. Tuan Ch’êng-shih recorded that the story came from Li Shih-yüan. Li

Shih-yüan had been told the tale by a man from the caves of South China who had long been in

the service of his family (Opie & Opie, 1992). Many believe that this tale shows considerable

usage from before this date (Jameson, 1932). Though this tale clearly existed in ancient China,

the tale is marginalized in Chinese culture, but very conspicuous in English culture (Mei, 1990).

It is also prevalent in American literature, if printed text and film are included within the

definition of literature.

The earliest European version was first published in 1544, in the Nouvelles Récréations et

Joyeux Devis of Jean Bonaventure Des Periers (Cox, 1893). Though not the first reporting of a

Cinderella tale in Europe, Giambattista Basil’s tale is probably the earliest full telling of

Cinderella from a historic and aesthetic perspective (Dundes, 1982). Basil wrote Lo Cunto de li

Cunte, a set of five days’ entertainment, each day consisting of ten stories. Lo Cunto de li Cunte

was published posthumously, in four volumes, in the years between 1634 to 1636 (Opie & Opie,

1992). The sixth diversion of the first day was “The Cat Cinderella” (Dundes, 1982), which was

originally published in the Neapolitan dialect; the semi-archaic form ensured the publication

would have minimal effect on the general stream of oral transmission (Opie & Opie, 1992). This

text was translated into Bolognese in 1742 and into Italian in 1747. Felix Liebracht translated it

into German in 1846, and Jacob Grimm wrote the introduction to that translation. The Grimm

brothers were surprised to find so many of their stories reported two hundred years before

(Dundes, 1982).

17

What constitutes a Cinderella story? There is an academic definition of the story cycle,

determined by folklorists and applicable to many different variants. These definitions vary based

on the categorization method used, but most include a persecuted heroine and natural or

supernatural assistance. There is also a definition that belongs to the populace, which requires a

shoe and a prince, among other things. These two characterization techniques are different, but

they cannot be completely divorced from each other.

Professional Scholarship

In 1893, Marian Roalfe Cox published a collection of 345 variants of the Cinderella tale,

tabulating them in Cinderella: Three Hundred and Forty-Five Variants of Cinderella, Catskin,

and Cap o’ Rushes (Cox, 1893). She separated the stories into five different types: Type A, B, C,

D, and E. Each type had different characteristics; tales of type E, for example, were exclusively

tales with a male protagonist. In Table 1, the types are listed. In 1951, Anna Birgitta Rooth wrote

a doctoral dissertation, The Cinderella Cycle, on the subject (Dundes, 1982). In the revised

edition of Aarne and Thompsons’s standard category of folk tales, published in 1962,

‘Cinderella’ and ‘Cap of the Rushes’ were assigned the designation of AT 510. AT 510 is

defined as follows:

1. The persecuted heroine. (a) The heroine is abused by her stepmother and stepsisters, and

(a1) stays on the hearth or in the ashes, and (a2) is dressed in rough clothing—such as a

cap of rushes, wooden cloak, and so on; (b) flees in disguise from her father who wants to

marry her; or (c) is cast out by him because she has said that she loved him like salt, or

(d) is to be killed by a servant.

2. Magic help. While she is acting as a servant (at home or among strangers) she is advised,

provided for, and fed (a) by her dead mother, (b) a tree on the mother’s grave, (c) a

18

supernatural being, (d) birds, or a goat, sheep, or cow. (f) When goat (cow) is killed, a

magic tree springs up from her remains.

3. Meeting the prince. (a) She dances in beautiful clothing several times with a prince, who

seeks in vain to keep her, or the prince sees her in church. (b) She gives hints of the abuse

she has endured as a servant girl, or (c) is seen in her beautiful clothing in her room or the

church.

4. Proof of identity. (a) She is discovered through the slipper test or (b) a ring, which she

throws into the prince’s drink or bakes into his bread. (c) She alone is able to pluck the

gold apple desired by the knight.

5. Marriage with the prince.

6. Value of salt. The father is served unsalted food and thus learns the meaning of the

heroine’s earlier answer.” (Zipes, 2012)

Hans-Jörg Uther further edited Aarne and Thompson’s category system in 2004. The

relations between the systems can be seen in Table 1 (Dundes, 1982).

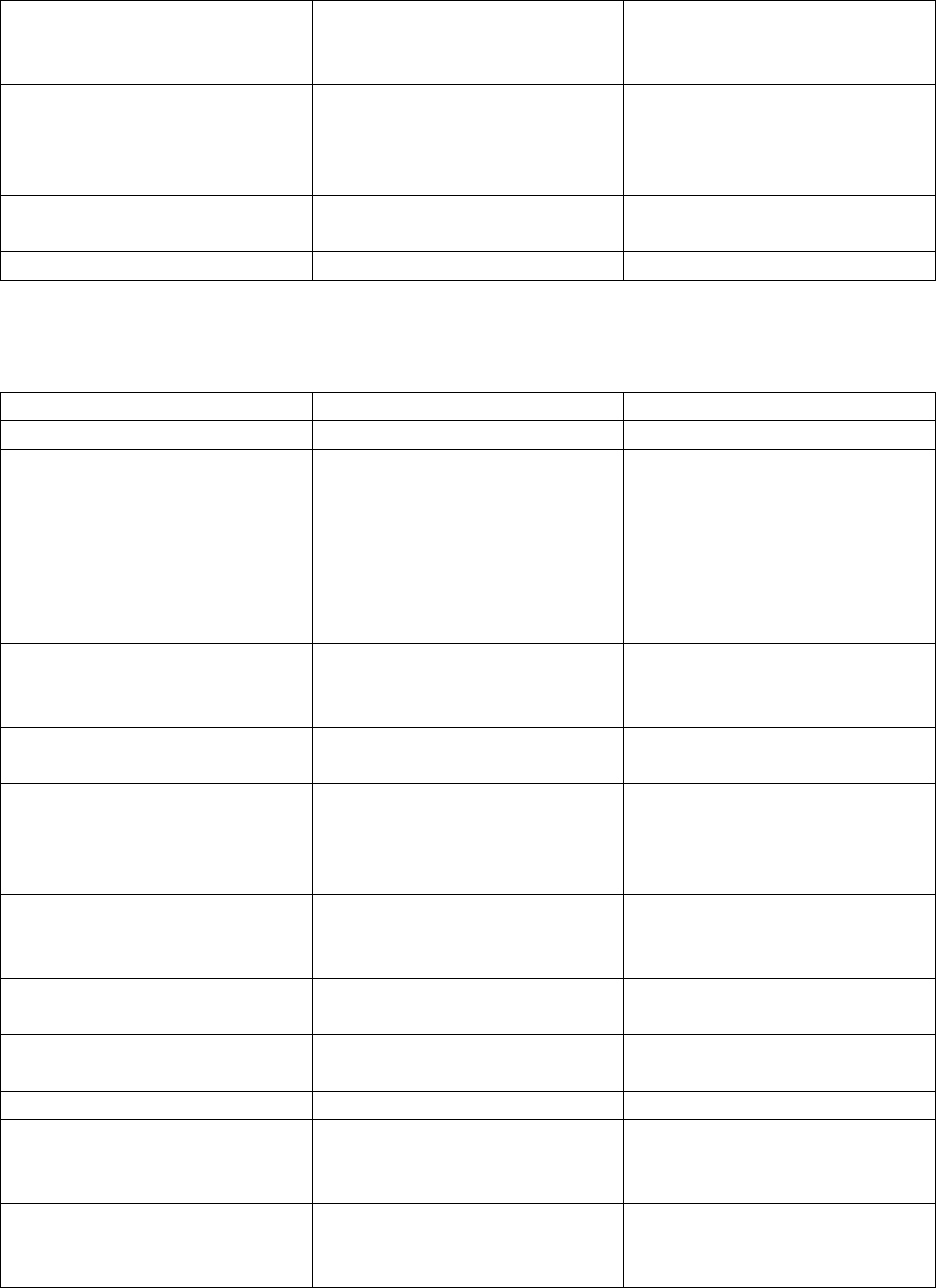

Table 1. Comparison between Cox, Rooth, Aarne-Thompson systems

Cox

Rooth

Aarne-Thompson

Type A. Cinderella

Type B

AT 510A. Cinderella

Type B. Cat-skin

Type B I

AT 510B. The Dress of Gold,

of Silver, and of Stars

Type C. Cap o’ Rushes

“

“

Type D. Indeterminate

Type A

AT 511. One-Eye, Two-eyes,

Three-Eyes

Type E. Hero Tales (Male

protagonist)

Type C

AT 511A. The Little Red Ox

----------

Type AB

AT 511 + AT 510A

Even with so many variants tabulated and accessible, the most familiar retellings of the

Cinderella tale, in literature studies and popular culture, are: ‘Aschenputtel’, by the Grimm

19

brothers (see Appendix A) and ‘Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre’, written by Charles

Perrault (see Appendix B). Of the two, Perrault’s tale is more widely recognized, mainly due to

film adaptations.

Path to the United States

Madame d’Aulnoy’s 1721 tale of ‘Finetta the Cinder-girl,’ published in the first volume

of her Collection of Novels and Tales, had already appeared in English when Perrault’s tale was

translated by Robert Samber and appeared in Histories or Tales of Past Times, published in

London in 1729 (Opie & Opie, 1992). Cinderella, though widespread in some parts of the world

“is not found as an indigenous tale in North and South America, in Africa, or aboriginal

Australia” (Dundes, 1986, p. 264). Perrault’s tale came to the present-day United States with

European immigrants. The story entered the ideology of the nation. The idea that a poor boy can

become president is “recited sub-vocally along with the pledge of allegiance in each classroom.”

“This rags-to-riches formula was immortalized in American children’s fiction by the Horatio

Alger stories of the 1860s and by the Pluck and Luck nickel novels of the 1920s (Yolen, 1977, p.

297).

Though some would argue that it is not a rags-to-riches story—rather it is a story about

riches recovered—that element has been bundled with the Cinderella story and it cannot be

removed from the popular conception. Books, plays, movies – Cinderella has infiltrated every

American cultural arena, though the titles may not bear the name. “When we speak about

Cinderella, we usually refer to a narrative type.” This visual-verbal type is derived from the

“interaction between Perrault’s and the Brother Grimm’s literary versions, plus Walt Disney’s

film adaptation.” Because of the globalized nature of commerce, the Perrault-Grimm-Disney

type has come to be understood as the correct version “even though the concept of a correct

20

versus an incorrect retelling contradicts [a] fundamental tenet of folklore storytelling.” Folk tales

are “based on a perpetual variation and transformation of all narrative formations” (Maggi, 2015,

p. 151).

Disney’s adaptations hold the world in thrall. It is the productions of that corporation that

provide the face and voice and breadth of many fairy tales, and particularly Cinderella.

Illustrations are significant to the history of any tale; illustrations are important to the history of

Cinderella. “Illustrations almost invariably determine the setting of a tale and the nature or

appearance of the leading characters; and can even, over the course of years, have an influence

on a tale’s popularity” (Opie & Opie, 1992, p. 6). Disney fairy tales are immensely popular. Part

of their popularity is due to the beautiful, immersive images that the studio has produced and

marketed. The imaginations of children are not the only imaginations “saturated with the Disney

version, graphic and verbal” (Warner, 1994, p. 416). The minds of adults, too, have been

inundated with the inescapable images. Disney Studios cannot be ignored when discussing the

popular conception of fairy tales, for many animated and live-action films have followed

Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

Popular Culture

Fairy tales are part of a web “of production and reception,” made of written and oral texts

and “translations, retellings, adaptations, critical interpretations, and relocations” (Maggi, 2015,

p. 80). Disney’s two feature length Cinderella adaptations will be studied to determine the

elements connected to the story in the popular imagination. The elements that lasted sixty-five

years—elements that were deemed necessary to include in a movie expected to return profits—

ought to exhibit those traits that the popular imagination requires to qualify the story as

Cinderella. A female protagonist seems to be indisputable, for example. Stories with a male

21

protagonist, though present in anthologies of fairy and folk tales, are not as prevalent. Walt

Disney himself identified with Cinderella (From Rags to Riches, 2005), but even he chose to

produce an animated feature with a female at the center.

In 1922, the Laugh-o-gram production of Cinderella featured a dark-haired Cinderella,

but the Disney 1950 Cinderella is blonde. The live action film released in 2015 showcases a

blonde Cinderella as well. Color and shape are very important elements to visual

communication. Perhaps the color scheme decided upon was best served with blonde hair.

Perhaps Disney and his artists were merely following the tradition of illustrated fairy tales.

Though a recessive trait in human populations, blonde hair dominates illustrations of fairy tales

(Warner, 1994). These illustrated texts were produced in Europe, a place that has “relatively few

gold deposits and has historically relied on gold traded from Africa and the East” (St Clair, 2016,

p. 86). Gold is precious; it does not tarnish and has been associated with the sun and divinity.

Golden hair shares some of the connotations of the precious metal: blondness is associated with

“sunshine, with the light rather than the dark, evoked untarnishable and enduring gold; all hair

promised growth, golden hair promised riches. The fairytale heroine’s riches, her goodness and

her fertility, her foison, are symbolized by her hair” (Warner, 1994, p. 378).

The etymology of blonde is not known for certain: it appears to be related to blandus

(Latin: charming), blundus (medieval Latin: yellow), blund (Old Germanic: yellow) or to the

French (for boys more than girls) blondin, blondinet. Chaucer uses the term blounde; this fades

until seventeenth century, at which point it is almost exclusively applied in feminine blonde.

Blonde hair suggested sweetness, charm, youthfulness–until the 1930-40s when it emerged as a

noun with hot, vampish overtones (Warner, 1994). Interestingly, the hair color is rarely ever

described as yellow (it is rather described as lightness, rather than yellowish) because of the

22

devilish associations traditionally connected to the color of yellow (St. Claire, 2016). It

corresponds to the English fair: in Old English, it meant beautiful or pleasing; in the thirteenth

century it meant free from imperfection or blemish; by the sixteenth century it came to mean a

light hue, clear in color. Fair also came to be used as a noun meaning beauty, as a guarantee of

quality—connoting all that is good, pure, and clean (Warner, 1994).

Cinderella, in Disney’s 1950 and 2015 films, is dressed in blue. Blue, too, can be (and

often is) associated with eternal, heavenly things. The Madonna is traditionally garbed in ultra-

marine, a very expensive, blue pigment. But the color blue, along with golden hair, is ascribed to

the feminine sphere. Until recently, children were dressed in a code of colors: pink is closer to

red, red is a very strong color—to the boys, the future leaders and public servants, pink was

given; to the girls, blue, lighter, delicate, retiring was given (Thompson, 2000).

“Although several well-known oral and literary tales celebrate ingenuity and slyness

rather than piety and honesty, morality has been widely accepted as a fundamental goal of the

fairy-tale genre” (Maggi, 2015, p. 159). And herein lies a problem many writers find with this

tale, although similar arguments, related to other stories, are made: somehow the tale shows the

morally upright way for a woman to act.

Social Implications

The social implications of Cinderella’s beauty—and her actions within the story—have

been substantially treated by professionals. Feminine youth and beauty—blonde hair and pale

skin too—are conventionally linked to linked to “privacy, modesty and an interior life,” a “lack

of exposure…either to the rays of the sun in outdoor work, or to the gaze of others” (Warner

1994, p. 368). Many find the norms that the story supposedly reinforces to be too dated. She is to

passively complete the household chores in her private sphere, completely divorced from the

23

public sphere. Here is one place that the 2015 Disney production diverges from the 1950

animation; Cinderella has very definite ideas about the correct path for the kingdom and she

voices them, though she is only a good, honest country girl (Lewis, 2015). The Grimm brothers,

in successive editions of ‘Ashenputtel,’ reduce the spoken lines given to the good women (i.e.,

Cinderella, Cinderella’s biological mother). This pattern can be seen throughout most of

Grimms’ tales; silence was a positive feminine attribute (Bottigheimer, 1986). The heroine of

Disney’s 2015 Cinderella has a voice and has a more active role than in the 1950 animation. This

change is an obvious response to critiques that have been made of the tale; it is also reflective of

the changing role of women in American society.

Feminists have approached the interpretation of fairy tales differently depending on the

political and social situation in which the writers live. There are three different assumptions that

have historically underlaid feminist writing in general, and the approach taken with Märchen.

The following is a list of the underlying assumptions of feminists’ critiques of fairy tales, listed

chronologically:

1. Women are artificially separated and wrongly considered unequal to men;

2. Women are naturally separate from men and rightly superior;

3. Men and women are naturally separate but potentially equal.

(Stone, 1986)

“The Märchen have been examined from all three approaches, and feminist reactions

have ranged from sharp criticism to firm support of the images of women presented in them”

(Stone, 1986, p. 234). Jack Zipes cannot see Cinderella as anything but “industrious, dutiful,

virginal and passive.” He suggests “the ideological and psychological pattern and message of

Cinderella do[es] nothing more than reinforce sexist values and a Puritan ethos that serves a

24

society which fosters competition and achievement for survival” (Zipes, 1979, p. 173). Others

have noted that to make such a ringing critique is to ignore “the subtle inner strength of heroines.

Cinderella, for example, emerg[es] as resourceful rather than remorseful, but not aggressively

opportunistic like her sisters” (Stone, 1986, p. 231).

Cinderella needs a fairy godmother; she seems unable to reach her goal without

assistance. Perrault inserted just such a moral at the end of his tale when he published it. The

reason for this miraculous, magical assistance may be the compilation of multiple things. She

may be kind and courageous or merely abused by her stepfamily, and in such a state deserves

intervention.

The abuse is enacted by women. Why, in folk and fairy tales is the trope of women

abusing other women so prevalent? Why are absent mothers so common? The absent mothers

can be read as a historical and social element when childbirth was a leading cause of death. If

fairy tales recount lived experiences, “the tensions, the insecurity, jealously and rage of both

mothers-in-law against their daughters-in-law and vice versa, as well as the vulnerability of

children from different marriages” may be heard within them (Warner, 1994, p. 238). The

“economic dependence of wives and mothers on the male breadwinner exacerbated—and still

does—the divisions that may first spring from preferences for a child of one’s own flesh”

(Warner, 1994, p. 238).

Many Disney films have mothers missing or replaced by surrogates, with the surrogates

rarely presented positively . “Tales of the wicked stepmother permeate every culture and from

early childhood pervade out consciousness” (Hughes, 1991, p. 54). Discrepancies between

positive experiences and these stories of heartless step-mothers do not seem to change the

pervasiveness of the theme (Hughes, 1991). It may be that experiences mirror the tale. Children

25

living with a biological parent and a step parent experience a higher percentage per population

unit of abuse than children living within their biological family (poverty is also a factor, but at

the same socioeconomic level, the trend remains). “Step-parents do not, on average, feel the

same child-specific love and commitment as genetic parents, and therefore do not reap the same

emotional rewards from unreciprocated parental investment. Enormous differentials in the risk of

violence are just one, particularly dramatic, consequence of this predictable difference in

feelings” (Daly & Margo, 1999, p. 38).

Historically, this also seems to be the case: “age-specific mortality of pre-modern

Friesian children was elevated in the aftermath of the death of either parent and, more tellingly,

that the risk of death was further elevated if the surviving parent remarried” (Daly & Margo,

1999, p. 36). Divorce rates are reduced with the presence of children in a current marriage; the

presence of children from previous marriages increases divorce rates (Daly & Margo, 1999).

The popular conception of the Cinderella story includes a glass shoe. In many other

variants of the Cinderella cycle, the means by which the girl is recognized may be something

different, a ring for instance. Perrault’s tale, so popular, has cemented a glass shoe. Many have

“accepted the tradition that the glass slipper in Perrault’s ‘Cinderella’ was originally made of

vair, fur or ermine,” and Perrault made a mistake, and copied the wrong word (Warner, 1994, p.

361). But, following Perrault, the shoe became “glass, and the logic of this symbolism, whether

he chose it or happened upon it, is perfect” (Warner, 1994, p. 361). For a shoe of glass cannot be

stretched, and it would be immediately obvious if a shoe fit—or if it did not (Opie & Opie,

1992). Glass is also fragile and will shatter easily; as such, there are connections that could be

made to a woman’s virginity (Dundes, 1982). “Leah Kavablum insisted that Cinderella really

gains freedom from kitchen and fireside, and that her prince is symbolic for inner strength. She

26

reminds readers that Cinderella’s slipper in Freudian symbolism is her own vagina, and thus her

regaining of it establishes her as an independent woman” (Stone, 1986, p. 231).

Bruno Bettelheim asserts that Grimm’s Cinderella is an active heroine who exhibits the

five phases of the human life cycle, as listed in Table 2 (Zipes, 1979), though Jack Zipes

condemns the Freudian and Jungian “plunges into the mysterious depths of the tales” as merely

“fish[ing] for what their psychological premises dictate” (Zipes, 1979, p. 41).

Table 2. Ashenputtel actions as phases of human life cycle

Human Life Phase

Action

Basic Trust

Relation with good mother

Autonomy

Acceptance of role in family

Initiative

Planting Twig

Industry

Hard Labor

Identity

Prince sees her dirty, beautiful

Cinderella must be chosen in her ratty state. This is made more evident in the 2015 film

adaptation, but she is recognized by the grand duke in servant’s garb in the 1950 animation.

However much kings or princes are enamored of Cinderella while she is in her beauteous

enchanted state, she cannot be won until…she has been recognized by her suitor in her

mundane, degraded state…Cinderella [may not] herself reveal her identity; nor may any

human being be a party to her secret. She must invariably return home from an outing

before the rest of the family, and must resume her workaday appearance so that they do

not know she has been out. She seems to be innately aware—if she has not received

actual instruction—that if she is recognized in her beauteous state she will never escape

27

servitude. Thus, however much the prince or king may have the recollection of a vision

of loveliness it is essential (in all but Madame d’Aulnoy’s literary rendering of the tale)

that the royal suitor accepts her as his bride while she is in her humble state. (Opie &

Opie, 1992)

The recognition of Cinderella as a servant brings about a marriage; the story ends here, as

Cinderella marries her prince. Fairy tales are formulaic, in both the popular imagination and the

academic field, and made of similar episodic events. Perrault’s tale as well as Disney’s animated

and live action tales, follow the structure set out by Vladimir Prop in Morphology of the Folktale

(Murphy, 2015). A table comparing Perrault’s tale and the Grimm version to Propp’s

morphology can be seen in Appendix C. Perhaps these decisions by the Disney corporation in

the 2015 film were merely a ploy to cement the superiority of Disney in this genre, to remind the

populace that they are the mogul of the film fairy tale. An effective way to establish a foundation

for rule is to connect oneself—visually and historically—to an older regime. Countless ancient

rulers have done this; a film director should not balk at such an action. Alluding to the 1950 film

validates the 2015 film production; the 1950 release was immensely popular, almost ensuring

that the 2015 live action release would likely be so. Since the live action film follows the 1950

plot structure with only small variances, it likely would not alienate fans of the animated film.

Critics point out that businesses exist, and continue to exist, by making money, by selling

a product that the population will consume. Because of the reliance on popular opinion, the

decisions made for Disney productions are ultimately in the hands of the public. This method of

film production has returned some of the power to the audience. As in the oral storytelling of

ages past, the audience interacts in the event, albeit remotely. Since the Disney Studio is still in

28

business—doing a very lucrative business—it has established itself as the popular imagination.

Its productions will continue to inform and be informed by public opinions.

Many films conform to the Cinderella cycle, setting the narrative in contemporary times

(e.g., Pretty Woman, Maid in Manhattan, Princess Diaries, etc). These exist along with Disney’s

creations. “The classical tale is also dissected into single tropes, such as the lost shoe or the

figure of the benign godmother…These loose tropes have a pervasive presence in current

popular culture” (Maggi, 2015, p. 163). Another technique is to set in contemporary times “well-

known characters of classical fairy tales” (Maggi, 2015, p. 163). This device could be interpreted

as “an enclosed space that keeps Cinderella and other major fairy-tale figures distant form the

rest of the world, as the symbolic representation of a transitional time, in which old and

formulaic narratives resist their inevitable transformation” (Maggi, 2015, p. 163).

The formulaic narratives have changed; they have morphed into new forms, changing

characteristics with changes in media. However, the metamorphosis is not complete: there are

obvious ties to older traditions. No story can exist in a vacuum, untethered; fairy tales have a rich

history and that history affects and informs the method of distribution, and the form of the tales.

Thus, modern film and literary adaptations of fairy tales are tied to popular folk tales.

29

Conclusion

Though a very old genre, fairy tales are still told in the modern world. Cinderella is an

example of a tale that has been told for hundreds, if not thousands of years—told throughout

most of the world. However, the primary medium for the expression of such stories is no longer

speech. Literary text superseded oral storytelling centuries ago. Film then overshadowed text in

the last century, coming with the advent of the moving picture. Several historical figures can be

associated with the transition from oral to text—most notably, Charles Perrault and the Grimm

brothers. Their names are still attached to printed collections of fairy tales sold today. Walt

Disney is most recognizably associated with the transition from print to film, bringing Cinderella

and other fairy tales to the screen.

The history of fairy tales ought to be understood. These tales that we consume,

internalize, personalize are not eternal forms. The tales have been molded, changed as they have

passed from one person, one generation, to another. Understanding those past changes gives

permission for alteration in the present. Fairy tales are not relics that must be maintained in their

current form; the tales are alive, fluid and should be understood as such.

Stories form the foundation of a nation. Folk and fairy tales form a collective culture as

well as—or perhaps better than—monuments to past grandeur or high ideals, for they are far

easier to access and to use than structures of stone. They are a great avenue for communication,

for teaching social customs and for discussing those same norms.

Other nation-states may cherish different stories; Cinderella is imbedded in the American

psyche. Every poor man has the chance to become president, every underdog athlete may beat

his competitors; these ideas are often described in relation to Cinderella, in the context of the

political and social freedom in America (Yolen, 1977). Cinderella is a tale about an individual’s

30

success, her triumph—not that of society at large. The American creed, too, may be easily

described as an individualistic one.

But Cinderella has a long history, longer by far than the United States. The longevity, the

prevalence of the Cinderella story must speak to some basic piece of human nature. As simple

and formulaic as it is, no one element can be touted as the sole reason for the popularity of the

Cinderella tale, for there are too many elements that make it up. Cinderella is a beautiful story: a

story of grace and maliciousness; a story of the past, and a story of the present.

31

References

Adler, G., & Hull, F. C. (Eds.). (1980). Archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.) (Vol.

9). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Allan, R. (1999). Walt Disney and Europe: european influences on the animated feature films

of Walt Disney. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Benson, S. (2003). Cycles of influence. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Biechonski, J. (2005). Fairy tales in adult psychotherapy and hypnotherapy. In Mental Health

and Psychotherapy in Africa (pp. 95-111). South Africa: UL Press of the University

Limpopo-Terfloop Campus.

Bottigheimer, R. B. (1986). Silenced women in the Grimms’ tales: the ‘fit’ between fairy

tales and society in their historical context. In R.B. Bottigheimer (Ed.), Fairy tales and

society: illusion, allusion, and paradigm (pp. 115-131). Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Cox, M. (1893). Cinderella: three hundred and forty-five variants of Cinderella, Catskin, and

Cap o’Rushes, abstracted and tabulated with a discussion of medieval analogues, and

notes. London: The Folk-lore society.

Daly, M., & Margo W. (1999). The truth about Cinderella: a Darwinian view of parental love.

New Haven: Yale University Press.

Disney, W. (1922). Cinderella [Motion picture]. United States: Laugh-o-gram Films.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Geronimi, C., Jackson, W., Luske, H. (Directors). (1950). Cinderella

[Motion picture]. United States: Disney Studios.

Dundes, A. (1982). Cinderella: a folklore casebook. New York: Garland Publishing.

Dundes, A. (1986). Fairy tales from a folkloristic perspective. In R. B. Bottingheimer (Ed.),

32

fairy tales and society: illusion, allusion, and paradigm (pp. 259-269). Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press.

Grimm, J., & Grimm, W. (1857). Aschenputtel. In Kinder- und Hausmärchen (D.L. Ashliman,

Trans.) (7th ed., pp. 119-26). Göttingen: Verlag der Dieterichschen Buchhandlung.

Hughes, C. (1991). Stepparents: wicked or wonderful? An indepth study of stepparenthood.

Brookfield: Gower Publishing Company.

Jameson, R. D. (1932). Cinderella in China. In A. Dundes (Ed.), Cinderella: a folklore

casebook (pp. 71-97). New York: Garland Publishing.

Le Guernic, A. (2004). Fairy tales and psychological life plans. Transactional Analysis Journal.

34(3), 216-222.

Lewis, T. (Producer), & Branagh, K. (Director). (2015). Cinderella [Motion picture]. United

States: Disney Studios.

Maggi, A. (2015). The creation of Cinderella from Basile to the brother Grimm. In M. Tatar,

The Cambridge companion to fairy tales (pp. 150-165). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Mei, H. (1990). Transforming the Cinderella dream: trom Frances Burney to Charlotte Brontë.

New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Murphy, T. P. (2015). The fairytale and plot structure. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Opie, I., & Opie, P. (1992). The classic fairy tales. New York: Oxford University Press.

Oring, E. (1986). Folk narratives. In E. Oring (Ed.), Folk groups and folklore genres: an

introduction (pp. 121-145). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Perrault, C. (1697). Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre (Robert Samber, Trans. 1729). In

I. Opie & P. Opie, The Classic Fairy Tales (pp. 123-127). New York: Oxford University

33

Press.

Schenda, R. (1986). Telling tales—spreading tales: change in the communication forms of a

popular genre. In R. B. Bottigheimer (Ed.), Fairy tales and society: illusion, allusion,

and paradigm (pp. 75-94). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Senehi, J. (2009). Folklore of subversion. In L. Locke, T. A. Vaughan, & P. Greenhill,

Encyclopedia of women’s folklore and folklife (xlvii-lvii). Westport: Greenwood Press.

St Clair, K. (2016). The secret lives of color. New York: Penguin Books.

Stone, K. (1986). Feminist approaches to the interpretation of fairy tales. In R. B. Bottigheimer

(Ed.), Fairy tales and society: illusion, allusion, and paradigm (pp. 229-236).

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sumpter, C. (2008). The Victorian press and the fairy tale. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thompson, Belinda. (2000). Impressionism: origins, practice, reception. Oxford: Thames and

Hudson.

Warner, Marina. (1994). From the beast to the blonde: on fairy tales and their tellers. New

York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

White, T. R. (1992). From Disney to Warner Bros.: the critical shift. Film Criticism, 16(3), 3-

16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44075967

Yolen, J. (1977). America’s Cinderella. In A. Dundes (Ed.), Cinderella: a folklore casebook

(pp. 21-29). New York: Garland Publishing.

Zipes, J. (1979). Breaking the magic spell: radical theories of folk and fairy tales. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Zipes, J. (1994). Fairy tale as myth, myth as fairy tale. Lexington: University Press of

Kentucky.

34

Zipes, J. (2006). Why fairy tales stick. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor, and Francis Group.

Zipes, J. (2012). The irresistible fairy tale: the cultural and social history of a genre.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Zipes, J. (2015). Media-hyping of fairy tales. In M. Tatar (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to

fairy tales, edited (pp. 202-219). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(2005). From Rags to Riches: The making of Cinderella [Motion picture]. United States: Walt

Disney Studios.

35

Appendix A

Aschenputtel

A rich man's wife became sick, and when she felt that her end was drawing near, she

called her only daughter to her bedside and said, "Dear child, remain pious and good, and then

our dear God will always protect you, and I will look down on you from heaven and be near

you." With this she closed her eyes and died.

The girl went out to her mother's grave every day and wept, and she remained pious and

good. When winter came the snow spread a white cloth over the grave, and when the spring sun

had removed it again, the man took himself another wife.

This wife brought two daughters into the house with her. They were beautiful, with fair

faces, but evil and dark hearts. Times soon grew very bad for the poor stepchild.

"Why should that stupid goose sit in the parlor with us?" they said. "If she wants to eat

bread, then she will have to earn it. Out with this kitchen maid!"

They took her beautiful clothes away from her, dressed her in an old gray smock, and

gave her wooden shoes. "Just look at the proud princess! How decked out she is!" they shouted

and laughed as they led her into the kitchen.

There she had to do hard work from morning until evening, get up before daybreak, carry

water, make the fires, cook, and wash. Besides this, the sisters did everything imaginable to hurt

her. They made fun of her, scattered peas and lentils into the ashes for her, so that she had to sit

and pick them out again. In the evening when she had worked herself weary, there was no bed

for her. Instead she had to sleep by the hearth in the ashes. And because she always looked dusty

and dirty, they called her Cinderella.

36

One day it happened that the father was going to the fair, and he asked his two

stepdaughters what he should bring back for them.

"Beautiful dresses," said the one.

"Pearls and jewels," said the other.

"And you, Cinderella," he said, "what do you want?"

"Father, break off for me the first twig that brushes against your hat on your way home."

So he bought beautiful dresses, pearls, and jewels for his two stepdaughters. On his way

home, as he was riding through a green thicket, a hazel twig brushed against him and knocked

off his hat. Then he broke off the twig and took it with him. Arriving home, he gave his

stepdaughters the things that they had asked for, and he gave Cinderella the twig from the hazel

bush.

Cinderella thanked him, went to her mother's grave, and planted the branch on it, and she

wept so much that her tears fell upon it and watered it. It grew and became a beautiful tree.

Cinderella went to this tree three times every day, and beneath it she wept and prayed. A

white bird came to the tree every time, and whenever she expressed a wish, the bird would throw

down to her what she had wished for.

Now it happened that the king proclaimed a festival that was to last three days. All the

beautiful young girls in the land were invited, so that his son could select a bride for himself.

When the two stepsisters heard that they too had been invited, they were in high spirits.

They called Cinderella, saying, "Comb our hair for us. Brush our shoes and fasten our

buckles. We are going to the festival at the king's castle."

Cinderella obeyed, but wept, because she too would have liked to go to the dance with

them. She begged her stepmother to allow her to go.

37

"You, Cinderella?" she said. "You, all covered with dust and dirt, and you want to go to

the festival?. You have neither clothes nor shoes, and yet you want to dance!"

However, because Cinderella kept asking, the stepmother finally said, "I have scattered a

bowl of lentils into the ashes for you. If you can pick them out again in two hours, then you may

go with us."

The girl went through the back door into the garden, and called out, "You tame pigeons,

you turtledoves, and all you birds beneath the sky, come and help me to gather:

The good ones go into the pot,

The bad ones go into your crop."

Two white pigeons came in through the kitchen window, and then the turtledoves, and

finally all the birds beneath the sky came whirring and swarming in, and lit around the ashes.

The pigeons nodded their heads and began to pick, pick, pick, pick. And the others also began to

pick, pick, pick, pick. They gathered all the good grains into the bowl. Hardly one hour had

passed before they were finished, and they all flew out again.

The girl took the bowl to her stepmother, and was happy, thinking that now she would be

allowed to go to the festival with them.

But the stepmother said, "No, Cinderella, you have no clothes, and you don't know how

to dance. Everyone would only laugh at you."

Cinderella began to cry, and then the stepmother said, "You may go if you are able to

pick two bowls of lentils out of the ashes for me in one hour," thinking to herself, "She will

never be able to do that."

The girl went through the back door into the garden, and called out, "You tame pigeons,

you turtledoves, and all you birds beneath the sky, come and help me to gather:

38

The good ones go into the pot,

The bad ones go into your crop.”

Two white pigeons came in through the kitchen window, and then the turtledoves, and

finally all the birds beneath the sky came whirring and swarming in, and lit around the ashes.

The pigeons nodded their heads and began to pick, pick, pick, pick. And the others also began to

pick, pick, pick, pick. They gathered all the good grains into the bowl. Before a half hour had

passed they were finished, and they all flew out again.

The girl took the bowls to her stepmother, and was happy, thinking that now she would

be allowed to go to the festival with them.

But the stepmother said, "It's no use. You are not coming with us, for you have no

clothes, and you don't know how to dance. We would be ashamed of you." With this she turned

her back on Cinderella, and hurried away with her two proud daughters.

Now that no one else was at home, Cinderella went to her mother's grave beneath the

hazel tree, and cried out:

Shake and quiver, little tree,

Throw gold and silver down to me.

Then the bird threw a gold and silver dress down to her, and slippers embroidered with

silk and silver. She quickly put on the dress and went to the festival.

Her stepsisters and her stepmother did not recognize her. They thought she must be a

foreign princess, for she looked so beautiful in the golden dress. They never once thought it was

Cinderella, for they thought that she was sitting at home in the dirt, looking for lentils in the

ashes.

39

The prince approached her, took her by the hand, and danced with her. Furthermore, he

would dance with no one else. He never let go of her hand, and whenever anyone else came and

asked her to dance, he would say, "She is my dance partner."

She danced until evening, and then she wanted to go home. But the prince said, "I will go

along and escort you," for he wanted to see to whom the beautiful girl belonged. However, she

eluded him and jumped into the pigeon coop. The prince waited until her father came, and then

he told him that the unknown girl had jumped into the pigeon coop.

The old man thought, "Could it be Cinderella?"

He had them bring him an ax and a pick so that he could break the pigeon coop apart, but

no one was inside. When they got home Cinderella was lying in the ashes, dressed in her dirty

clothes. A dim little oil-lamp was burning in the fireplace. Cinderella had quickly jumped down

from the back of the pigeon coop and had run to the hazel tree. There she had taken off her

beautiful clothes and laid them on the grave, and the bird had taken them away again. Then,

dressed in her gray smock, she had returned to the ashes in the kitchen.

The next day when the festival began anew, and her parents and her stepsisters had gone

again, Cinderella went to the hazel tree and said:

Shake and quiver, little tree,

Throw gold and silver down to me.

Then the bird threw down an even more magnificent dress than on the preceding day.

When Cinderella appeared at the festival in this dress, everyone was astonished at her beauty.

The prince had waited until she came, then immediately took her by the hand, and danced only

with her. When others came and asked her to dance with them, he said, “She is my dance

partner.”

40

When evening came she wanted to leave, and the prince followed her, wanting to see into

which house she went. But she ran away from him and into the garden behind the house. A

beautiful tall tree stood there, on which hung the most magnificent pears. She climbed as nimbly

as a squirrel into the branches, and the prince did not know where she had gone. He waited until

her father came, then said to him, "The unknown girl has eluded me, and I believe she has

climbed up the pear tree.

The father thought, "Could it be Cinderella?" He had an ax brought to him and cut down

the tree, but no one was in it. When they came to the kitchen, Cinderella was lying there in the

ashes as usual, for she had jumped down from the other side of the tree, had taken the beautiful

dress back to the bird in the hazel tree, and had put on her gray smock.

On the third day, when her parents and sisters had gone away, Cinderella went again to

her mother's grave and said to the tree:

Shake and quiver, little tree,

Throw gold and silver down to me.

This time the bird threw down to her a dress that was more splendid and magnificent than

any she had yet had, and the slippers were of pure gold. When she arrived at the festival in this

dress, everyone was so astonished that they did not know what to say. The prince danced only

with her, and whenever anyone else asked her to dance, he would say, “She is my dance

partner.”

When evening came Cinderella wanted to leave, and the prince tried to escort her, but she

ran away from him so quickly that he could not follow her. The prince, however, had set a trap.

He had had the entire stairway smeared with pitch. When she ran down the stairs, her left slipper

stuck in the pitch. The prince picked it up. It was small and dainty, and of pure gold.

41

The next morning, he went with it to the man, and said to him, "No one shall be my wife

except for the one whose foot fits this golden shoe."

The two sisters were happy to hear this, for they had pretty feet. With her mother

standing by, the older one took the shoe into her bedroom to try it on. She could not get her big

toe into it, for the shoe was too small for her. Then her mother gave her a knife and said, "Cut off

your toe. When you are queen you will no longer have to go on foot."

The girl cut off her toe, forced her foot into the shoe, swallowed the pain, and went out to

the prince. He took her on his horse as his bride and rode away with her. However, they had to

ride past the grave, and there, on the hazel tree, sat the two pigeons, crying out: