Case story and the interpretation of relative clause

marker by ESL learners in some selected schools in

Yaoundé

A Dissertation submitted to the Higher Teacher Training College (ENS)

Yaoundé in partial Fulfilment of the requirements for the award of D.I.P.E.S II

in English language

Par :

MEKANG NGOME Silvie

BA Linguistics

Sous la direction

EPOGE Napoleon

Senior Lecturer

Année Académique

2015-2016

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN

Paix – Travail – Patrie

********

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROUN

Peace – Work – Fatherland

*******

UNIVERSITE DE YAOUNDE I

ECOLE NORMALE SUPERIEURE

DEPARTEMENT DE Anglais

*********

UNIVERSITY OF YAOUNDE I

HIGHER TEACHER TRAINING COLLEGE

DEPARTMENT OF English

*******

AVERTISSEMENT

Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le jury de soutenance et mis à

disposition de l'ensemble de la communauté universitaire de Yaoundé I. Il est

soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci implique une obligation de

citation et de référencement lors de l’utilisation de ce document.

D'autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite encourt une poursuite

pénale.

Contact : [email protected]

WARNING

This document is the fruit of an intense hard work defended and accepted before a

jury and made available to the entire University of Yaounde I community. All

intellectual property rights are reserved to the author. This implies proper citation

and referencing when using this document.

On the other hand, any unlawful act, plagiarism, unauthorized duplication will lead

to Penal pursuits.

Contact: [email protected]

i

DEDICATION

This work is dedicated to my brother Derek Mpako Ngome.

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This piece of work was realized with the help of many people to whom I extend my profound

gratitude. My sincere thanks go to my supervisor, Dr Napoleon Epoge, whose criticisms,

suggestions, and valuable advice were vital towards the realization of this work. My immerse

gratitude goes to all the lecturers of The Department of English for their academic assistance

throughout my stay at the Higher Teacher Training College Yaoundé (ENS). Their

devotedness to their work equipped me with the skills I needed to pursue this work to the end.

Special thanks go to my parents; Rev. Elias Ngome and Florence Ngome, my siblings

Renee Ajebe, Moses Ngome and Derek Mpako, for the financial and moral support they

provided for the realization of this work.

My heartfelt thanks go to the following persons who helped me in many different

ways during this research: Colvis Niba Ngwa, Manuela Enanga, Roseline Ashu, and

Charlotte Besong, and my classmates at the Higher Teacher Training College, Yaounde.

iii

ABSTRACT

This study explores the structural configuration and interpretation of the case form of the

relative clause marker by second language learners. This study is anchored on the theoretical

paradigm, Case Theory (Chomsky 1981), which stipulates the theta –roles of noun phrases in

relation to the verb used in a sentence. Hence case grammar is a system of linguistic analysis

which focuses on the link between the subject and object of a verb and the grammatical

context it requires. To accomplish the aim of this study, a production test was designed to

elicit data from students of four secondary schools in Yaounde. Findings reveal that these

learners of English face difficulties in interpreting the relative clause markers as they

substitute the relative pronoun “which” for “who”, “ who” is also substituted for an object

relative pronoun “whom” in some cases and in some others , the relative pronoun “that”

substitutes its counterpart “whom” and “which”. Hence they use the case forms of relative

pronouns arbitrarily without respecting the input- oriented feature specifications spelt out by

the Case Theory. This is a call for concern as this raises serious pedagogical questions with

regard to the teaching and learning of English as a second language.

iv

RESUME

Cette recherche porte sur l‟analyse de la configuration structurelle et du cas du pronom relatif

tel qu‟utilisé par les élèves ayants l‟anglais pour deuxième langue. La théorie du cas formulée

par Chomsky en 1981 nous a servis de paradigme. Cette théorie examine donc le rapport du

syntagme nominal avec le verbe utilisé dans une phrase. Le cas grammatical se révèle comme

étant un système basé sur le rapport sujet-objet ainsi le rapport verbe-contexte grammatical

dans l‟analyse linguistique. Pour atteindre le but de cette étude, nous avons amené les élèves

provenant de quatre établissements de Yaoundé à produire des rédactions à partir desquelles

nous avons collecté nos donnés. Notre analyse révèle que ces élèves ont les difficultés à

interpréter les pronoms relatifs car ils substituent « which » par « who ». « Who » est aussi

remplacé par les pronoms relatifs objets « whom » et « which ». Ainsi, leur usage du pronom

relatif est arbitraire car ne respectant pas les règles qui régissent l‟emploi des ce pronom par

la théorie du cas. Ceci soulève donc d‟importantes questions pédagogiques au sujet de

l‟enseignement et même de l‟apprentissage de l‟anglais comme seconde langue.

v

CERTIFICATION

I certify that this research work, entitled “Case Theory and the Interpretation of Relative

Clause Marker by ESL Learners in Some Selected Schools in Yaoundé” was carried out by

Silvie Mekang Ngome, a student of the Department of English, Higher Teacher Training

College, Yaounde.

Supervisor

Napoleon Epoge

Senior lecturer

Department of English

ENS Yaoundé

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEDICATION........................................................................................................................... i

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... ii

ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................ iii

CERTIFICATION ................................................................................................................... v

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................... viii

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE STUDY ......................................................................... x

CHAPTER ONE:GENERAL INTRODUCTION ................................................................ 1

CHAPTER TWO:THEORETICAL PREMISE AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE ..... 5

2.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 5

2.1Theoretical Premise ........................................................................................................... 5

2.1.1 Case theory .................................................................................................................... 5

2.1.2 The Theta –role ............................................................................................................. 7

2.1.3 Theta criterion ............................................................................................................... 9

2.2 Review of Related Literature ......................................................................................... 10

2.2.1 The Notion of Relative Pronouns and Clauses ............................................................ 10

2.2.2 Related Empirical Studies ........................................................................................... 16

CHAPTER THREE:METHODOLOGY ............................................................................ 20

3.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 20

3.1 Area of study .................................................................................................................. 20

3.2 Population of study ......................................................................................................... 20

3.2. Instrument of data collection ......................................................................................... 21

3.3. Procedure of data collection .......................................................................................... 22

3.4. Method of data analysis ................................................................................................. 23

3.5. Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 24

CHAPTER FOUR:DATA ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION OF RESULTS ............ 25

4.0. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 25

4.1 Respondents‟ general performance in the interpretation of the semantic role of the

relative clause marker ........................................................................................................... 25

4.1.1Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “which” as object of the verb....... 27

4.1.2Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “who” as subject .......................... 30

4.1.3Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “whom: as object of the verb ....... 32

4.1.4Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “which”: as subject of the verb .... 35

vii

4.2 Feature specifications ..................................................................................................... 37

4.2.1 Identification of subject “which” as object pronoun ................................................... 38

4.2.2 Identification of object “which” as subject pronoun ................................................... 38

4.2.3 Identification of subject “who” as subject pronoun .................................................... 39

4.2.4 Identification of object “whom” as object pronoun .................................................... 39

4.2.5 Substitution of “who” for “whom” .............................................................................. 39

4.2.5 Substitution of “which” for “who” .............................................................................. 40

4.2.1 The problem of Case ................................................................................................... 41

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 43

CHAPTER FIVE:SUMMARY OF FINDINGS, PEDAGOGICAL RELEVANCE AND

CONCLUSION ...................................................................................................................... 44

5.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 44

5.1 Summary of Findings ..................................................................................................... 44

5.2 Pedagogical Relevance ................................................................................................... 47

5.3 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... 49

5.3.1 Recommendation to educational authorities ............................................................... 49

5.3.2 Recommendations to school Authorities ..................................................................... 50

5.3.3 Recommendations to teachers ..................................................................................... 51

5.3.4 Recommendations to parents ...................................................................................... 51

5.3.5 Recommendation to curriculum designers .................................................................. 52

5.3.6 Recommendations to learners ..................................................................................... 52

5.3.7 Recommendations to course book writers .................................................................. 52

5.3.8 Recommendations to linguistic centers ....................................................................... 52

5.4 Suggestion for further research ...................................................................................... 53

5.5 Difficulties Encountered by the Researcher ................................................................... 53

5.6 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 54

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... 55

APPENDIX ............................................................................................................................. 62

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table1: The distribution of the population of study ............................................................. 21

Table 2: Respondents‟ performance in the interpretation of the semantic role of the relative

clause marker ........................................................................................................................ 25

Table 3: Respondents performance in the identification of “which” as object of the verb .. 28

Table 4: Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “who” as subject .................... 30

Table 5: Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “whom: as object of the verb. 33

Table 6: Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “which”: as subject of the verb.

.............................................................................................................................................. 35

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Fig.1: General mean percentage graph of respondents‟ performance .................................. 27

Figure 2: Respondent‟s performance in the identification of “which” as object of the verb

.............................................................................................................................................. 29

Figure 3: Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “who” as subject ................... 31

Figure 4: Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “whom: as object of the verb.

.............................................................................................................................................. 34

Figure 5: Respondents‟ performance in the identification of “which”: as subject of the verb.

.............................................................................................................................................. 36

x

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE STUDY

ESL English as Second language

EFL English as a foreign language

EA Error Analysis

GBHS Government Bilingual High School

GBPHS Government Bilingual Practising High School

INFL Inflection

L1 First language

L2 Second language

NP Noun phrase

RC Relative clause

SLA Second language acquisition

S, O, C, A Subject, object, complement, adjunct

Spec Specifier

+tns tense

V verb

Prep preposition

e.g. Example

1

CHAPTER ONE

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

The present study explores the structural configuration and interpretation of the case form of

the relative clause marker by English as Second language (henceforth ESL) learners. The

empirical focus is on the relationship between the verb in the embedded relative clause and

the relative clause marker. With regard to this, the present chapter, which acts as the

presentation of what the whole work is all about, handles the main issues that sustain the

research: background, research problem, aim, significance of the study as well as the thesis

statement, research questions and the structure of the work.

The understanding of how input and output affect comprehension and production of

the target forms and structures in one‟s second language (henceforth L2), is a key issue in

second language acquisition (henceforth SLA) research and has been the subject of several

studies which try to examine the relative effects of input-based as compared to output-based

instructional conditions (Nagata, 1998; Allen, 2000; Erlam, 2003). Relative clause

constructions in English have been considered to be complicated and problematic for most

ESL learner, compared with some other structures in the language (Celce-Muricia& Larsen –

Freeman, 1999). Research in SLA has revealed that the problems with which English learners

in general are confronted concern first language (henceforth L1) influence (Gass, 1984; Chen,

2004), avoidance (Li, 1996; Mamniruzzuman,2008), and overgeneralization ( Erdogan,2005).

This phenomenon characterizes the English of ESL learners because English in non-native

setting exists alongside indigenous language and most people who study English here come

to the English language classroom with knowledge of at least an L1. This is even more

evident in the Cameroonian setting.

The Cameroonian linguistic ecology harbours a multitude of languages. It is mapped

out by indigenous languages, Indo –European languages (English and French), and Hybrid

languages (Pidgin English and camfranglais). Biloa (2004:1) succinctly presents a clear

picture of this linguistic diversity in Cameroon thus:

Cameroon is generally looked at as the microcosm of Africa. From a variety of

perspectives, it is Africa in miniature. Historically, it is a zone of confluence and

convergence of the civilization that have impacted Africa. Linguistically, three of

2

the four linguistic phyla attested in Africa are represented therein. To say the list, it

is linguistics melting –pot or patchwork. Apart from the local languages, there are

two languages of European importation; French and English. On top of that, two

hybrid languages: Pidgin English and camfranglais. Biloa (2004:1)

Cameroon is a multilingual country comprising of 247 indigenous languages, two

official languages and Cameroon Pidgin English (Breton and Fohtung, 1991). Although

Ethnologue (2002) puts the number of indigenous languages for Cameroon at 279, these

figures are challenged by scholars such as Wolf (2002) for not seeing an accurate reflection

of the current language situation. Some dialects of the same languages are sometimes

considered as different languages, Echu (2003).

The two official languages, French and English came into the Cameroon linguistic

scene in 1906 when Britain and France divided the country into two unequal parts. These

colonial masters imposed the languages in the newly acquired territory, both in areas of

administration and education. This situation was reinforced after Cameroon became

independent and at reunification in 1961, when English and French become the official

languages of Cameroon as the country opted for the policy of official languages bilingualism.

(Echu 2003). This also bred two sub-systems, and the French sub-systems. In the English

sub-system, the English language is the medium of instruction and learners of English here

are considered as ESL learners. In the French sub-system, the French language is the medium

of instruction and learners of English here are considered as EFL learners.

With this background, L2 learners of English in Cameroon have a difficult puzzle in

striving to set the parameters of the English language. Because the rhetorical structures of

these languages surrounding the acquisition of English in this setting are not the same as that

of English, the structural configuration of what is written in this setting often exhibit features

that do not meet input-based features specifications. However, language learners need to

posses an intuitive ability required to identify certain grammatical elements in a sentence and

structural configuration. Research has shown that many students as well as teachers face a lot

of difficulties in identifying the subject and object of the verbs in complex sentences. This is

noticeable mostly in complex sentences with relative clause.

3

A relative clause modifies a noun or a noun phrase. They are often introduced by

relative pronouns such as, who, whom, which, and that. A relative clause gives extra

information about the noun in the matrix clauses (e.g. the book which I am reading comes

from the bookshop). In this example, the relative clause marker is the relative pronoun

“which”. This relative clause marker introduces the relative clause “which I am reading”. The

latter provides addition information to the noun phrase “the book”. A syntactic analysis of the

embedded relative clause reveals that the relative clause marker “which “is the object of the

verb “reading”. Thus, this is the object of the verb. A detailed discussion of this phenomenon

is done in the next chapter.

Besides , in order to better interpret the position of the relative clause markers as

either playing the role of a subject or object of a verb in the embedded clause, it is very

important to take the case theory as the theoretical paradigm that underlie the study. Case is a

morph-syntactic property of noun phrases, which identifies a noun phrase„s function or

grammatical relation in a sentence. This theory analyses the surface syntactic structure of

sentences by studying the combination of deep cases which have semantic roles such as

agents, objects, benefactor, location or instrument which are required by a specific verb. Take

for instance the verb “to give” in English requires an Agent (A), an Object (O), and a

Beneficiary (B) as in “Susan (A) gave groundnuts (o) to the farmers (B)”.

Consequently, in view of the foregoing discussion, the present study aims to explore

and analyse how L2 learners in some selected schools in Yaounde interpret the relative clause

marker of the embedded relative clause, in a complex sentence, in relation to the verb in the

embedded clause. The study is limited to relative pronouns and to upper sixth arts students of

A1, A3, and A5 series.

In order to carry out an in-depth investigation into this phenomenon, the following

research questions underlie the study:

1. How do Upper Sixth Arts students interpret the semantic role of relative clause

markers in complex sentence?

2. What are the difficulties noticed in the Upper Sixth arts students processing of the

semantic role of the relative clause markers in English?

4

The outcome of the study is expected to be of benefit to learners, teachers and the

educational authorities in various ways. This study is an appropriate pedagogical material in

the teaching of English to ESL learners. This is because it provides a rationale for

constructing language lessons in ESL context which are more appealing to this set of

students, taking into consideration the syntactic configuration that will develop learner‟s

competency and autonomy. The findings will inspire teachers to improve on their

competence and adopt new and better approaches to teaching relative pronouns and adverbs.

In the same light, it is of help to students in highlighting the features that will enable them to

become efficient in using relative pronouns. Moreover, it is going to create awareness in

English language teachers of the need to raise the consciousness of learners‟ semantic role of

the relative pronouns and adverbs.

This study is divided into five chapters. Chapter One, which act as the presentation of

what the whole work is all about, handles the main issues that sustain the research:

background, research problem, aims, scope, significance of the study as well as the thesis

statement, research questions and the structure of the work. Chapter Two presents and

discusses the theoretical paradigm, the case theory (Chomsky 1981), and reviews related

literature. Chapter Three presents the methodology for this research. This chapter describes

research instruments, sample population, procedure of data collection and the method of data

analysis. Chapter Four presents and analysis the data collected. Chapter Five presents the

summary of the findings, gives the pedagogical relevance and makes recommendations.

5

CHAPTER TWO

THEORETICAL PREMISE AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0 Introduction

This chapter is focused on the theoretical paradigm (2.1) and review of related literature

(2.2).

2.1Theoretical Premise

The theoretical framework adopted from Chomsky is the Case Theory (Chomsky 1981). This

theory stipulates a morph syntactic property of noun phrases which identifies a noun phrase‟s

function or grammatical relation in a sentence. Hence, it analyses the surface syntactic

structure of sentences by studying the combination of deep cases which have semantic roles

such as agents, objects, benefactor location or instrument which are required by a specific

verb. Case is assigned by means of feature checking in a spec- head configuration and is

morphologically visible. Therefore, it deals with a special property that all noun phrases are

assumed to have. If they lack this feature, the sentence which contains the phrase is rendered

ungrammatical. In English there are generally three main cases: nominative Scase, accusative

case, and genitive case. The nominative case is a linguistic situation whereby a noun is the

subject of a clause as in “Coffee is good”. In this sentence, the noun “coffee” which is the

subject of the verb “is” is in the nominative case. Besides, the accusative case is a linguistic

situation whereby the noun in a clause is the object of the verb as in “I like coffee”. In this

clause, the noun “coffee” which is the object of the verb “like” is in the accusative case. In

the same line of thought, the genitive case expresses possession as in (John‟s book).

2.1.1 Case theory

According to Chomsky (1981), Case grammar is a system of linguistic analysis which

focuses on the link between the number of subjects and objects of a verb and the grammatical

context it requires. In the context of transformational grammar, the theory analyses the

surface syntactic structure of sentences by studying the combination of deep cases; that is,

semantic or theta roles such as: agent, object, benefactor, location or instrument, which a

specific verb may require. For instance the verb’ give’ in English requires three theta roles:

an agent (A), an object (O) and a beneficiary (B) as illustrated below

6

1) Susan gave mangoes to the children.

AGENT OBJECT BENEFICIARY

In this example, the noun “Susan” is the Agent of the verb “give”, the noun “Mangoes” is the

object of the verb “gave” and the noun “children” is the beneficiary of the action of giving.

Hence, Case Theory enables a clause to result in the surface-structure (S-structure) order.

This can be perceived by the fact that all NPs are assigned cases which are based on

government or specifier-head agreement (Chomsky, 1986b:24). As a result, case is assigned

by a set of case assigners (v, prep, and INFL (+tns)) to the constituent they govern. For

instance, INFL (+tns) assigns nominative case to the NP it governs (i.e., the subject,

reflecting the fact that tensed sentences require subject expressions); v assigns accusative

case to the NP it governs (i.e., the object) and prep also assigns accusative case to the NP it

governs. The nominative and the accusative cases are known in syntactic literature as external

and internal arguments respectively as illustrated by the example below.

2) Paul washed himself.

In the above example, the verb “wash” assigns two theta roles: Agent (Paul) and Patient

(himself). The AGENT is the external argument and the PATIENT is the internal argument.

Hence, in a case whereby the NP is an internal argument of a verb, the verb assigns an

accusative case to it and when it is the external argument of the verb, the verb assigns a

nominative case to it. With regard to this, Paul is assigned the nominative case by the verb

wash and himself is assigned the accusative case by the same verb “wash”. Consequently,

Paul is referred to as the nominative case while himself is the accusative case.

In addition, Fillmore (1968) defines case grammar theory as a semantic valence

theory that describes the logical form of a sentence in terms of a predicate and a series of case

labeled arguments such as Agent(A), Instrumental(I), Dative(D), Objective(O), Factive (F)

and Locative(L). The theory provides a language universal approach to sentence semantics as

well as a semantic description of the verbs of a language. According to Fillmore (ibid), each

verb selects a certain number of deep cases which form its case frame. Consequently, the case

frame describes a number of aspects of semantic valence of verbs and nouns as exemplified

below.

7

i. The AGENTIVE (A): the instigator of the action identified by the verb. It must

always be chosen as a subject in simple active sentences.

3) Peter broke the window.

ii. INSTRUMENTAL (I): the object casually involved in the state or action identified by

the verb. It may occur as the subject of the verb.

4) The hammer broke the plates.

5) John killed the Monkey with a knife

iii. DATIVE: the entity being affected by the action of the verb

6) Samuel believed the story.

iv. OBJECTIVE: the case of anything represented by a noun whose role in the action

identified by the verb is defined by the semantic interpretation of the verb itself

7) The story is true

v. FACTIVE: an object resulting in a state identified by the verb

8) Jason built a chair.

vi. LOCATIVE: the case which identifies the location identified by the verb

9) The box contains the toys.

According to (Cook 1989:8), the case system should consist of the smallest possible number

of cases that is satisfactory for the classification of all verbs of a language. Furthermore the

case system should have universal character meaning that it is applicable in every language.

2.1.2 The Theta –role

This theory is a constraint on the X-bar Theory (Chomsky, 1981) as a rule within the system

of the Government and Binding Theory. The theta-theory is concerned with the distribution

and assignment of theta-roles. A theta-role is a status of thematic relation (Chomsky

1981:35). In order words, it describes the connection of meaning between a predicate and a

verb a constituent which is selected by this predicate. The selection of a constituent by a head

which is based on meaning is called s-selection (semantic-selection) and those based on

grammatical categories are known as the c-selection.

8

10) a. Paul loves Deborah.

AGENT THEME

b. The teacher hit Dora

In (10), the verb „love‟ has two theta-roles to assign: agent (the entity who loves) and the

theme (the entity being loved). In accordance with the theta-criterion, each theta-role needs

its argument counterpart. The two arguments Paul and Deborah in (10a) and teacher and

Dora in (10b) occupy different semantics relationships with their verbs respectively. The

argument NP Paul in the subject position refers to the entity that is the subject of the verb

loving and the teacher of hitting. The NP Deborah in (10a) expresses the entity that is loved,

that is, the theme; and Dora, in (10b), the direct object of the NP expresses the entity that is

hit. In this case, it is referred to as the patient. Hence, the theta role that is assigned by the

verb to their NPs involved in the activity is summarized as follows:

i. Agent (a participant that causes something to happen or is responsible for

something happening or has a conscious control over something happening);

ii. Patient/Experience(someone who experiences the action denoted by the verb);

iii. Goal ( entity towards which an activity expressed by the verb is directed),

iv. Source (entity from which something is moved as a result of the activity

expressed by the verb);

v. Location(it marks the stationary position of an object with respect to some other

object);

vi. Theme (an object that is in steady motion or it is the topic of discussion).

Fillmore (1968: 16)

To expatiate the above-stated facts, the verb „fear‟ assigns two roles: patient/theme

roles (e.g., The mouse fears the cat);give assigns three roles: agent, patient and goal (e.g.,

Molly gave the keys to her sister); see assigns three roles: experience, theme, and location

(e.g., Clovis saw a beetle on the table); borrow assigns three roles: agent, theme and source

(e.g., John borrowed a car from Dora).As demonstrated above, the predicate takes relevant

information from the lexicon and assigns a theta role to each of its syntactic arguments. As a

result, it can be said that theta theory examines how lexical items behave in relationship with

other lexical items. (Epoge 2011).

9

2.1.3 Theta criterion

According to Chomsky quoted in Epoge (2011), the theta criterion states that each argument

of the verb receives one and only one theta role and each theta role is assigned to one and

only one argument. The theta criterion makes sure that a verb is associated with just the right

theta role. For instance, the verb catch is linked with an agent as subject (catcher) and a

patient as object (the caught). Thus the theta criterion ensures that the verb catch occurs with

two lexical NPs and that agent and patient are assigned correctly to its subject and object

(Epoge 2011). This is because when there is a one-to- one mapping of argument to theta –

role, the theta criterion is satisfied and the sentence is deemed grammatical(Carnie 2007:225).

In the case of a relative clause construction, the relative pronoun “who” has two case

forms to spell out the external argument and the internal argument respectively. The external

argument (the nominative case) has the form “who” and the internal argument (accusative

case) has the form “whom” as illustrated below.

11) a. This is the man who teaches English.

b. This is the man whom we visited yesterday.

In (11a) the relative pronoun “who” is the subject of the verb “teaches‟ and in (11b) the

relative pronoun “whom” is the object of the verb “visited”. Hence, in (11a) the relative

pronoun is an external argument and in (11b) it is an internal argument. In the same vein, the

relative pronoun in (11a) is the AGENT and in (11b) the BENEFICIARY.

It is healthy to point out here that not all relative pronouns have two distinct case

forms. This is the case of the relative pronoun „which‟. This relative pronoun has the same

case form for both the external and internal argument as illustrated below.

12) a. This is the book which carries the effigy of the Head of State.

b. This is the book which I bought yesterday.

In (12a), the relative pronoun “which” is the subject of the verb “carries” and in (11b) it is the

object of the verb “bought”. Hence, the external argument and the internal argument, have the

10

same case form. Consequently, the distinction of the nominative and accusative cases is not

spelt out at the orthographic level. This is only possible through a syntactic analysis.

It is healthy to point out here that English follows the normative grammatical tradition

which associates the subjective pronouns with the nominative case of pronouns in inflectional

languages such as Latin and objective case with the oblique cases (especially accusative and

dative cases) in such languages (Quirk et al 1985).Thus, Case Theory is adopted for this

study to check how the input-oriented feature specifications are interpreted by English as

Second language (ESL) learners in some selected schools in Yaoundé.

2.2 Review of Related Literature

The review of related literature is done in two phases: the notion of relative pronouns and

clauses (2.2.1) and related empirical studies (2.2.2

2.2.1 The Notion of Relative Pronouns and Clauses

A relative pronoun introduces a relative clause (Quirk et al 1995). The question that arises

here is what is then a clause? Task and Stockwell (2007), cited in Epoge (2015pg 81-82),

holds that

A clause is a grammatical unit consisting of a subject and a predicate, and every

sentence must consist of one or more clauses. For example, a simple sentence

consists only of a single clause (e.g., Mary has gone to school). A compound

sentence consist of two or more clauses of equal rank usually joined by a

coordinating conjunction such as and, or, but, yet, so (e.g., the students went to

school but the teacher did not come). Then a complex sentence consists of two or

more clauses where one out ranks the others which are subordinated to it (e.g., If the

rain continues, the wheat will rot).

In English syntax, a relative clause is a certain type of sub-clause, at least containing a subject

and a verb that is used to modify nouns, pronouns or sometimes whole phrases. Relative

clauses are usually introduced by a relative pronoun establishing a link to what is being

modified (which is called the „antecedent‟). This assertion is illustrated by the example

below.

11

12) The handbag which you ordered last month has arrived.

In (12) above, the relative pronoun “which” introduces the relative clause “which you

ordered last month”. A relative pronoun is different from a personal pronoun in that the

element which comprises or contains the relative pronoun is always placed at the beginning

of the clause, whether it is subject, complement or object. Also, relative pronouns resemble

personal pronouns in that they have co reference to an antecedent (Quirk et al 1995). For

instance, the antecedent of the relative pronoun which in (12) is handbag. In this case, as in

most relative clauses, the antecedent is the preceding part of the noun phrase in which the

relative clause functions as post modifier: [the handbag [which you ordered last month]].

Hence, a "relative clause is a clause which modifies the head of a noun phrase and typically

includes a pronoun or other elements whose reference is linked to it" (Mathews 2007:341). It

is introduced by a relative pronoun who, whom, which, that or whose or by a relative adverb

where, when or why.

It is healthy to point out here that there are two types of relative clauses: defining and

non-defining. Defining relative clause (also called identifying relative clauses or restrictive

relative clauses) gives detailed information defining a general term or expression. Defining

relative clauses are not put in comma. Defining relative clauses are often used in definitions

as in the sentence “A seaman is someone who works in a ship”. In this sentence, the relative

clause “who works in a ship” defines the antecedent "a seaman". So, the function of the

defining relative clause is to give essential information about the antecedent.

Non-defining relative clauses (also called non-identifying relative clauses or

non-restrictive relative clauses) give additional information on something but do not

define it. Non-defining relative clauses are put in commas. In the sentence “ My father,

who is in the corner, is a judge”, the relative clause is a non-defining one because it gives

extra information about the antecedent “my father". The relative clause is put in commas

because it gives extra information and it can be deleted without changing the meaning. And

the new sentence will be “My father is a judge”.

Either defining or non-defining relative clause, the latter is introduced by a relative

pronoun. A relative pronoun is a pronoun that marks a relative clause within a larger

sentence. It is called a "relative" pronoun because it "relates" to the word that it modifies as in

the following example:

12

13) The person who phoned me yesterday is my brother.

In the above example, "who” relates to "person", which it modifies and introduces the relative

clause "who phoned me yesterday”. Hence, a relative pronoun is a type of pronoun which

introduces a relative clause in a sentence to qualify a preceding noun called the antecedent.

14) The pastor whom Paul was expecting has died.

In the above example the antecedent of whom is the pastor. The antecedent is vital because it

determines which relative pronoun is to be used. In a case where the antecedent has one or

more persons, these relative pronouns who, whom, or whose are employed. These relative

pronouns fall under three main case forms: nominative, accusative, and genitive respectively.

The nominative case who is used when a person is the subject of the verb.

15) The trader who sells toys is an illiterate.

In the above example, the relative pronoun who is the subject of the verb sells and its

antecedent is the NP, the trader. The accusative case form whom is employed when it is the

object of a verb or a preposition

16) Paul is a prophet whom everyone worships.

17) This is the man to whom the money was paid.

In (16) the relative pronoun whom is the direct of the verb worships and its antecedent is the

NP prophet. Genitive case (expressing ownership) pronoun whose, relates possession. It

denotes possessor as (18) exemplifies..

18) Children whose parents are poor are intelligent.

In addition, the relative pronoun which is employed, when either the subject or object of the

verb is a thing or an animal as illustrated in (19)

19) a. The tomatoes which I bought yesterday are rotten.

b. Christina took the bag which was on the table.

13

In (19a), the relative pronoun which is the direct object of the verb “bought”, and its

antecedent is the NP tomatoes. In (19b) the relative pronoun which is the subject of the verb

“was” and its antecedent is the NP bag.

It is important to point out here that, unlike personal pronouns, relative pronouns have

the double role of referring to the antecedent which determines gender selection (e.g.,

who/which) and of functioning as all of, or part of, an element in the relative clause which

determines the case form for those items that have case distinction (e.g., who/whom). Hence,

Quirk et al (1995:1245) holds that;

Part of the explicitness of relative clauses lies in the specifying power of the relative

pronoun. It may be capable of (i) showing concord with its antecedent, that is, the

preceding part of the noun phrase of which the relative clause is a post modifier

[external relation]; and (ii) indicating its function within the relative clause either as

an element of clause structure (S, O, C, A), or as a constituent of an element in the

relative clause (internal relation)

In view of the above-stated, the focus of the present study is on the internal relation.

An English relative pronoun represents the antecedent within the relative clause, usually in

the position they would have in a corresponding declarative clause. They point out or

reinforce the grammatical function of the relativised NP in the relative clause by case –

marking and position and they strengthen the co-reference relation between the relativsed NP

and the antecedent by agreement in gender and number. Relative pronouns in English behave

differently from relative clauses in other languages. According to Mckee and McDaniel

(2001), relative pronoun distribution is very limited and appears to be influenced by linear

distance, depth and especially extractability that is, whether a trace is acceptable. In English

relative clauses, relative pronoun is generally in complementary distribution with traces in

(41) , where the trace is possible, the relative pronoun is not: in ( 42), where the trace is not

possible , the relative pronoun is not: in (42), where the trace is not possible , the relative

pronoun is.

14

(41)a). That‟s the girl that I like t

i

b). That‟s the girl that I like her.

(42) a) That‟s the girl that I don‟t know what

t

did.

b.) That‟s the girl that I don‟t know what she did.

(Adapted from Mckee and McDaniel, 2001)

Many linguists have contributed significantly to the literature of relative clause acquisition.

The aspects they have explored concern whether there is a universal markedness relationship.

Besides, transfer issue is also taken into account in the acquisition process (Odlin 1989) at the

same time; psycholinguistic factors are also considered in determining the order of relative

acquisition.

Gass (1979) investigated the acquisition of English relative clause by adult L2 learners of a

variety of linguistic backgrounds with the attempt to determine the relationship between

transfer and universal factors in the second language acquisition (SLA). The native learners

were learners of French and Arabic. Data from seventeen high- intermediate and advanced

learners were tested by sentence combination and free composition task. The results indicate

the acquisition of relative clauses by adult L2 learners was primarily governed by universal

phenomena. The easiest position to relativise being subject position. However, genitive was

the exception. Gass provided two possible explanations for this. First, genitive is uniquely

restricted to “whose”, allowing no other markers. Second, the relative ease of genitive has to

do with its position. In the sentence like “the man whose daughter John loves went to China”.

“Whose daughter” is viewed as a unit and interpreted as a direct object of the verb” loves”,

which accounts for the ease of relativisation of genitive case. This study also showed

universal principle is indispensable in the understanding and interpretation of second

language data. In the same vein, Izumi (2003) tested three hypotheses of relative clause

acquisition on subjects of various backgrounds. It was found out that the overall order of

difficulty can be predicted by the matrix positioning with the matrix object position being

easier than the matrix position. The difficult order can be predicted by the relative clause

types as in Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy (NPAH). He came to the conclusion that

NPAH based on different rationales can be seen to be complementary to each other since

15

NPAH is associated to the effect of canonicity with relative clause is related to the notion of

processing interruption in the matrix sentence.

According to Chomsky (1986), English relative clause is an embedded clause, which is

contained inside the NP it modified. English relative clause involves the movement of Wh-

relative pronoun or empty relative pronoun to the specifier position of complement phrase in

the embedded clause. This movement leaves a trace in the position from which the wh-phrase

has moved. Hence the moved wh-phrase is an operator which binds the trace it leaves behind.

In English wh-operator can be either overt such as who, which, that, whom or null when they

are overt. The head complimentizer must be null (except subject relative clause) as in (35)

when the wh operator is null, the complementizers may be either that or null, as in (36). In

English relative clause, relative pronouns should co –exit with wh- movement, otherwise

ungrammaticality will occur.

(35) a. the girl

i

[CP

e

[I like wh]

i

] is here.

b. the girl i[cp who

i e

[ I like t

i

]]is here.

(36) a. the girl

i

[OP

i

that [I like t

i

]] is here

b. the girl

i

[ OP

ie

[ I like t

i

] ] is here.

Since wh movement is restricted by subjacencey principle under which a constituent can only

be moved over a single bounding category (S or NP in English), in other words, movement

should not take place beyond more than one bounding category (S or NP in English) in other

words movement should not take place beyond more than one boundary node. And in

English, NP and TP are bounding nodes. If wh-movement in RCS violates subjecency

principle, relative will occur as examples in (37) and (38).

(37) [NP this is the man [CP who (m) [TPEmesworth told me when [TP he will invite

him.]]]].

(38) [NP this is the man [CP who (m) [TP Emsworth made [NP the claim that [TP he will

invite him]]]]].

(Adapted from Haegeman, 1991).

16

2.2.2 Related Empirical Studies

Relative clause constructions in English have been considered to be complicated and

problematic for most EFL and ESL learners, compared with some other structures in the

language (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999). Research in second language

acquisition has revealed that the problems with which English learners in general are

confronted concern first language (L1) influence (e.g. Gass, 1984; Chang, 2004; Chen,

2004), avoidance (e.g. Chiang, 1980; Gass, 1980; Li, 1996; Maniruzzuman, 2008), and

overgeneralization (e.g. Selinker, 1992; Erdogan, 2005).

Learners of a second language are likely to rely on the knowledge of their mother

tongue when faced with certain kinds of problems in second language learning or

communication. That is, they transfer the forms and meanings from L1 to the

production and comprehension in the target language. Such reliance upon learners‟ first

language sometimes appear to make them successful in L2 acquisition, thus viewed as

facilitation. Nevertheless, it is often shown that influence from L1 knowledge can also

have a negative effect on L2 learning, where the distance between L1 and L2 is great. With

respect to L2 acquisition of English relative clauses, evidence of both positive and negative

transfer is outstanding (Gass, 1984; Chang, 2004; Chen, 2004).

Avoidance, like L1 transfer, seems to play an important role in second

language acquisition of relative clauses. According to Ellis (1994), learners avoid using

linguistic structures which they consider difficult due to differences between their native

language and the target language. While first language transfer causes them to produce

errors in L2, avoidance behavior leads them to an omission of the L2 construction the

use of which they are not completely certain about. One of the classic studies as to

avoidance in L2 RC production is Schachter (1974), which revealed some flaws of error

analysis (EA) as this approach of L2 study failed to account for the occurrence of avoidance.

To be specific, she focused her study on the use of English relative clauses by native speakers

of four different languages (Persian, Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese) in comparison with

the English relative clauses used by American English speakers. It is discovered that the

Chinese and Japanese speakers produced fewer errors on English relative clauses than did the

Persian and Arabic participants because they avoided using English relative clauses which are

right-branching. Gass (1980), using a sentence-combining task and a written composition,

found that avoidance of L2 relative clauses is related to the degree of markedness in

17

that more marked relative clause types have more likelihood to be avoided. Gass

demonstrated that L2 English learners in the first task appeared to avoid relative clause

structures which are more marked, such as the object-of-preposition relative as in “He

has a book which I am interested in”.Maniruzzaman (2008) investigated Bengali EFL

learners‟ avoidance behavior. More than 90 % of the participants admitted in the

questionnaire and the interviews that they adopted avoidance behavior on purpose in their

learning and using English. Put differently, the learners avoided producing some complex

English structures, e.g. relative clauses, in both speaking and writing. A great number of

learners attributed their avoidance to the dissimilarities between L1 and L2, and to the

difficulty of L2 structures.

Another feature identified in EFL learners‟ use of English relative clauses deals with

transfer of training. This occurs when L2 learners apply rules they have previously learned

from their teachers or textbooks (Selinker, 1992). Unfortunately, if such instruction or

textbooks place an emphasis on only some structures of a grammar point, at the

expense of the others, learners may develop, in a limited manner, the knowledge of that

grammar point in L2 and overproduce only what they have learned or are used to, not aware

of the other constructions which are more advanced. To make it worse, in case the past

training or textbooks contain wrong information on that L2 grammar point, learners are

inclined to incorrectly use such structures having been taught (Ellis, 1985, 1994).

Overgeneralization is another common process used by those acquiring their native

language as well as learners of L2 (Gass and Selinker, 2001; Selinker, 1992). As

regards L2 acquisition, according to Richards et al. (2002), overgeneralization is a

process in which a learner extends the use of a grammatical rule of linguistic item beyond

its acceptable uses in the target language. This phenomenon occurs when learners try to

formulate a linguistic rule, based on the language data they have been exposed to or

instructed, without being aware of exceptions. As far as L2 relative clause acquisition is

concerned, English learners face challenges with the differences between a restrictive

relative clause (My sister who lives in Chicago has two children), and a non-restrictive

relative clause (My sister, who lives in Chicago, has two children) (Celce-Murcia and Larsen-

Freeman, 1999). On the other side of the spectrum, Akiko (2011) examines the relationship

that exists between sentence processing and individual differences in working memory

capacity. The question he addresses is whether the performances of second language (L2) in

18

processing relative clauses are similar to those of native speakers depending on one‟s

working memory. His findings reveal that having a lower working memory capacity seems to

hinder processing a sentence in a way similar to the native speakers. Hence, he argues that the

inability of the L2 learners to produce L2 sentences in the manner that is commonly preferred

by the native speakers seems to lead to lower comprehension accuracy in the relative clause

sentences, especially in the more-difficult-to-comprehend English object-gap. In the same

vein, Epoge (2015) investigated second language learners of English in Cameroon processing

and processing strategies of both the subject and object noun phrases (NP), in sentences with

embedded relative clause, in order to assign the correct meaning to the sentence. He collected

data from university students who performed a sentence comprehension task consisting of

subject- subject, object- subject, subject - object and object- object. His findings reveal that

processing difficulties can be linked with the poor mastery of clausal elements, as well as the

non-linguistic factors such as working memory limitations.

Also, Mere Bakkal (2010) investigated the techniques of relative clauses to Turkish speakers.

Relative clauses have always been an important issue to the EFL/ESL learners of their

complex syntactic structure and therefore being a learning problem to the language learner.

He collected data and his findings reveal that the informants‟ use of “which” instead of

“whose “in genitive construction is problematic to Turkish learners. Deletion of the subject

pronoun which results in ungrammatical sentence is an additional difficulty. Likewise, Theres

Wikefiord (2014) carried a research on “relative pronouns, relative clauses”. One of the aims

of this study is to explore Swedish learner‟s choice and usage of relative pronouns in English.

One of the hypotheses that underlie the study was that zero construction rarely utilized. The

results indicate that the constraint on relative pronouns choice is non-restrictive clause is

difficult for many learners adhere to in writing. Another line of research focused on the

effects of the instruction on relative clause acquisition for L2 learners. Aarts & Schils (1995)

compared the production of Dutch learners of English on sentence –combing tasks done

before and after three lectures on relative clauses, observed significant effects of instruction

on learner‟s performance of relative clauses. While several studies have been conducted to

examine Chinese and English relative clauses contrastively, research concerning how the

differences between Chinese and English relativisation affect the acquisition of Chinese

learners of English is scant among the limited amount of studies examining Chinese learner‟s

relative clauses. For example Schechter (1974) examined the composition data written by

Persian, Arabic, Chinese and Japanese learners of English. She observed that Chinese and

19

Japanese groups produced significantly fewer relative clauses than did Persian and Arabic

groups. She explained that it is because the native language from relative clauses strikingly

different ways. She also noted that while Chinese and Japanese do not use relative clauses

with great frequency, they use them with a high degree of accuracy when they do use them.

In the same vein, Liu (1998) investigated English relative clauses produced by junior high

school students in Taiwan. The author collected data using picture- identification (PID),

ordering (OR) and grammaticality judgment (GJ) tasks and observed little L1 interference in

the process of second / foreign language acquisition. On the other hand, Chiang (1981)

examined the errors in English majors writing and found that interference from L1 is a

common but not major, source error. The results show that subjects misuse relative pronoun,

such as the use of that for where, or vice versa.

With regard to the fore-going discussion, the present study is similar to the previous

studies in that they are all centered on complex sentences with relative clauses. Focus is on

relative clauses and/or relative pronouns. However, the study differs from the previous

studies in many perspectives. It centers on the interpretation of relative clause markers byESL

learners of English in a multilingual context. It equally focuses on ESL learners who have

been exposed to the English language since primary school and have been studying English

language for more than twelve years (i.e. six years in primary school and seven years in

secondary school). In addition, this study looks into the semantic property of the relative

clause marker in complex sentences with relative clauses, the property which none of the

previous has examined.

20

CHAPTER THREE

METHODOLOGY

3.0 Introduction

This chapter is concerned with the description of the methodology adopted for the present

study. It presents and describes the area of study (3.1), population of study (3.2), instrument

of data collection (3.3), procedure of data collection (3.4) and method of data analysis (3.5).

3.1 Area of study

This work was carried out in Yaounde, the headquarters of the Centre Region of the Republic

of Cameroon. It was conducted specifically in four schools in Yaoundé: Government

Bilingual High School Essos, Government Bilingual Practicing High School Yaounde,

Government Bilingual High School Etoug-ebe Yaounde and English High School Yaounde.

These schools were chosen first because they are secondary high schools and the students

come from different linguistic backgrounds. Also, it was thought worthy to take schools from

different denominations: government and private as cited above. In addition, since the focus

of the present study was on learners of English as a second language, these schools were

chosen to meet the exigencies of the study.

3.2 Population of study

The respondents for this study involved Upper Sixth Arts Student of the four schools. This

population was chosen because English Language is one of their main subjects both in class

and in their official examinations and it is believed that these students have been studying the

language for a period of about fourteen years: seven years in the primary school, five years in

the First Cycle and two years in the Second Cycle. On a whole, 80 students took part in the

test. The table below records the population of study.

21

Table1:Thedistribution of the population of study

SCHOOL

NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS

GBHS Essos

20

GBPHS Yaounde

20

GBHS Etoug-ebe

20

EHS Yaounde

20

TOTAL

80

As can be seen in the table above, 20 respondents were randomly selected from each school

and, when the number of respondents was tallied, it came up to 80 respondents who

participated in the production test.

These respondents were chosen because they have been exposed to the English

language in the classroom for at least 14 years (i.e. seven years in Primary School and seven

years in Secondary/high school). It is worthy of note that these respondents come to the

English language classroom with a knowledge of their mother tongues, French and

Camfranglais. However, these respondents prefer speaking French and more often than not

English language in a formal setting.

3.2. Instrument of data collection

The instrument used in the collection of data was a Production Test. This production test was

conceived to assess respondents‟ knowledge of relative clause markers, and how often they

use it in their writings taking into consideration the notions of case. The test which comprised

of 05 questions or items was made up of two tasks: the Multiple Choice Comprehension Task

(MCCT) and the Essay task. The MCCT task required respondents to explicitly identify the

relative clause marker in the relative clause construction provided as either functioning as the

subject or object of the verb given. This was done to find out the function of the relative

pronouns to which the respondents analyzed. The respondents were asked to identify the

relative pronouns in the construction by ticking against the right alternative. Sample tokens of

the MCCT question are given below.

22

1. The book which I bought yesterday is interesting.

a) “which” is the subject of the verb “bought” Yes [ ] No[ ]

b) “which” is the object of the verb “bought” Yes [ ] No[ ]

c) “which” is neither the subject nor the object of the verb “bought” Yes[ ] No[ ]

2. This is the police who arrested the thief.

a) “who” is the subject of the verb “arrested” Yes[ ] No[ ]

b) “who” is the object of the verb “arrested” Yes[ ] No[ ]

c) “who” is neither the subject nor the object of the verb “arrested” Yes[ ] No[ ]

With regard to the essay task, an essay topic was given on which the respondents were

expected to write freely. The respondents were expected to write an essay of not more than

150 words on the topic “An accident you witnessed in your neighbourhood”. The various

tasks were structured in such a way as to meet the exigencies related to the interpretation of

the relative clause markers as either the object or subject of the verb in the relative clause.

They test lasted one hour.

3.3. Procedure of data collection

The production test was drafted and presented to the supervisor for correction and

endorsement. After cross-checking and adoption of the production test, the researcher set out

for field investigation. This test, just as the scope stipulates, was destined for Upper Sixth

students in four different schools in Yaounde. The choice of these classes was simply as a

result of their exposure to the English Language. The teachers of the various schools were of

great help in the collection of the data. The permission was sought from the school authorities

and from the teachers teaching English in each of the classes randomly selected to administer

the test. Each teacher voluntarily gave up his or her hour to enable me to administer the

production test even though they had the pressure to finish their syllabus in view of the

forthcoming GCE Advanced-Level examination.

The teachers had to inform their learners some days before the test was administered.

During the administration of the test, the researcher was accompanied and assisted by the

teacher teaching the class to ensure that the students take the exercise seriously. The

production test was administered to the respondents as a class test. All the written instructions

were in English. The teachers were cooperative and rendered help such as the distribution of

the test papers to respondents, invigilation and collection of the test papers at the end of the

23

test. All the learners present in each of the classes at the time of administration wrote the test

and all the scripts from all these classes were collected and marked. The number of scripts

from the four schools was classified and analyzed making a total of 80 scripts treated.

3.4. Method of data analysis

The data acquired was marked, analyzed and any response that respected the input-oriented

semantic role of the relative clause marker got a point and any other got no point. The

responses which respected the input-oriented feature specifications were identified and

classified. This brought about the establishment of five tables which record the number of

instances produced in setting the input-oriented feature specifications and the percentage

scored, as well as the number of instances that do not respect the input-oriented feature

specifications. To make the result more feasible, the percentage scored was captured on mean

percentage graph.

In order to obtain these percentages, the following formula was used:

Y% = X/N x 100/1, where

X= number of students who gave the same response to a question

Y = percentage gotten from the sum of number of answers

N= the total number of instances provided

All these tables as well as the graphs were analysed discussed and explained bringing out the

salient points. Furthermore, feature specifications, in the data provided, were identified and

categorized. They were accompanied by explanations and examples to illustrate the point

made.

As far as the essay component was concerned, the essence was to see the extent to

which, even in their free speech, respondents violated the semantic role of relative clause

markers.

24

3.5. Conclusion

This chapter handled the methodology adopted for this study. This chapter presented the

sample population, the instrument of data collection, the procedure of data collection and the

method of data analysis. From every indication, data collected for the present research was

done in a scientific way and the analysis go in the same light as far as scientificity is

concerned, leaving no room for subjectivity.

25

CHAPTER FOUR

DATA ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

4.0. Introduction

This chapter presents and analyses the data collected. The analysis is based on the respect

and non-respect of the input-oriented feature specifications as far as the semantic role of

relative clause markers is concerned.

4.1 Respondents’ general performance in the interpretation of the semantic role of the

relative clause marker

The relative pronoun, when it is found in a sentence, can either play the role of a subject of

the verb or the object of the verb. Hence, respondents were expected to identify the role

played by each of the relative pronouns in the sentences which were given in the production

test. Structures such as “The book which I bought yesterday is interesting” were used to illicit

data. The result of their performance is presented in the table below.

Table 2: Respondents’ general performance in the interpretation of the semantic role of

the relative clause marker

SCHOOL

SETTING INPUT

PARAMETER

NON-SETTING OF INPUT

PARAMETER

TOTAL

Number of

instances

%

Number of

instances

%

GBPHS Yaounde

119

49.6

121

50.4

240

GBHS Essos

100

41.7

140

58.3

240

GBHS Etoug-ebe

119

47.5

121

50.4

240

EHS Yaounde

84

35

156

65

240

TOTAL

422

44

538

56

960

26

The result in the table above portrays that respondents produced 422 (44%) instances

whereby they respected the parameter settings of the input-oriented feature specifications

with regard to the interpretation of the semantic role of the relative pronouns tested. They

equally produced 538 (56%) instances whereby they used other parameter settings which

violate the feature specifications of the input.

As concerns the different institutions, the respondents from Government Bilingual

Practicing High School Yaounde produced 119 (49.6%) instances whereby they set the input

feature specifications in the interpretation of the semantic role of the pronouns in question;

and 121 (50.4%) instances whereby they violated the input feature specifications. The

respondents in Government Bilingual High School Essos produced 100 (41.7%) instances

whereby they respected the input feature specifications and 140 (58.3%) instances wherein

they violated the semantic role input feature specifications. The respondents from

Government Bilingual High School Etoug-Ebe produced 119 (49.6%) instances whereby they

set the input feature specifications in the interpretation of the semantic role of the pronouns in

question; and 121 (50.4%) instances whereby the violated the input feature specifications.

Respondents from English High School Yaounde produced 84 (35%) instances which

respected the input parameter settings and 156 (65%) instances which violated the input

parameter settings.

In all, no group of respondents produced a number of instances that is above average.

The best score (119 instances) was produced by the respondents from Government Bilingual

Practicing High School Yaounde and Government Bilingual High School Essos. The worst

performance was registered by the respondents from English High School (84 instances).

These results show that there is call for concern as far as the interpretation of the semantic

role of relative clause markers in embedded sentences was concerned. The mean percentage

graph below graphically presents the results in a clearer and more explicit manner.

27

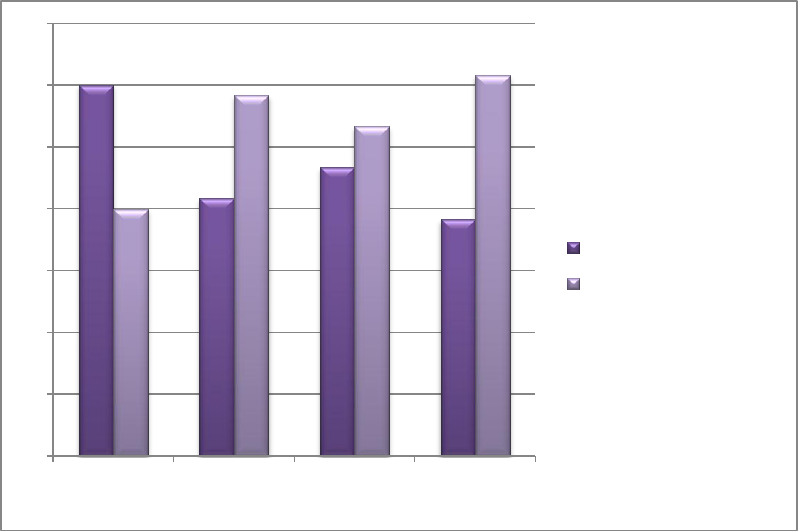

Fig.1: General mean percentage graph of respondents’ performance

As can be seen in the mean percentage graph, respondents from GBPHS scored 48.6

% in the interpretation of the semantic role of the relative clause marker and 54.4% in

violating the parameter settings of semantic roles. Respondents from GBHS Essos scored

41.7% in setting the parameter settings and 58.3% in violating the input parameters in

semantic role interpretation. Respondents from GBHS Etoug-ebe scored 47.5% in respecting

the semantic roles feature specifications and 52.5% in failing to set the parameters; and

respondents from EHS Yaounde scored 35% in respecting the input feature specifications and

65% in violating the parameter settings. The statistics in the graph portray a lack of mastery

of the relative clause markers as well as the inability to interpret the semantic role of relative

clause markers in embedded sentences.

4.1.1Respondents’ performance in the identification of “which” as object of the verb

There were eighty scripts examined. A total number of two hundred and forty occurrences

interpreted the semantic role of relative clause marker in the embedded sentence. This figure

was got by counting the number of frequency in the twenty scripts multiplying the number by

the number of alternative answers given per school which summed up to sixty instances. The

total number of each school was then added to give a grand total of two hundred and forty

49.6

41.7

47.5

35

50.4

58.3

52.5

65

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

LBA GBHS ESSOS GBHS ETOUG EBE EHS

setting input parameter none setting input parameter

28

instances “which” that were analysed. The following table records the classification of

respondents‟ performances in the identification of “which” as object of the verb per each of

the schools.

Table 3: Respondents performance in the identification of “which” as object of the verb

school

Setting input parameter

None setting of input

parameter

Total

Number of

instances

%

Number of

instances

%

LBA

21

35

39

65

60

GBHS

ESSOS

25

41.7

35

58.3

60

GBHS

ETOUG EBE

29

48.3

31

51.7

60

EHS

13

21.7

47

78.3

60

Total

88

36.7

152

63.3

240

The result in the table above shows that respondents produced 88 (36.7%) instances whereby

they respected the parameter settings of the input-oriented feature specifications with regard

to the interpretation of the semantic role of the relative pronoun tested. They also produced

152 (63.3%) instances whereby they used other parameter settings which violate the feature

specifications of the input.

As concerns the different institutions, the respondents from Government Bilingual

Practicing High School Yaounde produced 21(35%) instances whereby they set the input

feature specifications in the interpretation of the semantic role of the pronouns in question;

and 39 (65%) instances whereby the violated the input feature specifications. The

respondents in Government Bilingual High School Essos produced 25(41.7%) instances

whereby they respected the input feature specifications and 35 (58.3%) instances wherein

they violated the semantic role input feature specifications. The respondents from

Government Bilingual High School Etoug-Ebe produced 29(48.3%) instances wherein they

set the input feature specifications in the interpretation of the semantic role of the pronouns in

29

question; and 31 (51.7%) instances whereby the violated the input feature specifications.

Finally, respondents from English High School Yaounde produced 13 (21.7%) instances

which respected the input parameter settings and 47 (78.3%) instances which violated the

input parameter settings.

In all, no group of respondents produced a number of instances that is above average.

The best score (29 instances) was produced by the respondents from Government Bilingual

High school Etoug-Ebe and Government Bilingual High School Essos. The worst

performance was registered by the respondents from English High School (13 instances).

These results show that there is call for concern as far as the interpretation of the semantic

role of relative clause markers in embedded sentences was concerned. The mean percentage

graph below graphically presents the results in a clearer and more explicit manner.

Figure 2: Respondent’s performance in the identification of “which” as object of the

verb

As can be perceived in the mean percentage graph, we will notice that respondents from

GBHS Etoug-Ebe scored 48.3 % in the interpretation of the semantic role of the relative

clause marker and 51.7% in violating the parameter settings of semantic roles. Also,