REP ORT T O C ONGRE S S

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY • OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

June 2022

Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 1

SECTION 1: GLOBAL ECONOMIC AND EXTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS ..................... 6

U.S. ECONOMIC TRENDS .............................................................................................................. 6

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN SELECTED MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS .................................... 18

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS .................................................................................................................. 42

ENHANCED ANALYSIS UNDER THE 2015 ACT ............................................................................ 47

SECTION 2: INTENSIFIED EVALUATION OF MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS ........ 52

KEY CRITERIA ........................................................................................................................... 52

TRANSPARENCY OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE POLICIES AND PRACTICES ......................................... 57

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................................................................................................. 59

ANNEX 1: DEVELOPMENTS IN GLOBAL IMBALANCES .............................................. 62

GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS IN THE REPORT................................................................. 65

This Report reviews developments in international economic and exchange rate policies

and is submitted pursuant to the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, 22

U.S.C. § 5305, and Section 701 of the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015,

19 U.S.C. § 4421.

1

1

The Treasury Department has consulted with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and

International Monetary Fund management and staff in preparing this Report.

1

Executive Summary

Following a steep contraction of the global economy in 2020 due to the impact of COVID-

19, recovery began to take hold in 2021, and has been most pronounced in economies that

undertook strong macroeconomic policy support and where a larger share of the

population has been vaccinated. In 2022, however, Russia’s unprovoked and unjustifiable

war against Ukraine has upended the global outlook. Most importantly, Russia’s war is

having a devastating human toll, from lives lost, to families displaced internally or

becoming refugees. It is also imperiling the global recovery through supply disruptions

and rising commodity prices, as well as increasing food insecurity and inequality. The IMF

projects global growth to slow from an estimated 6.1% in 2021 to 3.6% in both 2022 and

2023, which is 0.8 and 0.2 percentage points lower for 2022 and 2023 than the IMF’s

projections in January 2022.

Countries will experience varying degrees of spillovers from the war depending on the

breadth and depth of their economic ties with Russia and Ukraine, reliance on net imported

commodities, and pre-war macroeconomic policies and vulnerabilities. Macroeconomic

policy responses should therefore be carefully calibrated. Countries most affected by the

war should redeploy targeted fiscal support to protect the most vulnerable, while net

commodity exporters should build fiscal buffers during the upswing in prices and

investment in economic diversification where appropriate. Meanwhile, the COVID-19

pandemic is not yet behind us and actions to support the global rollout and distribution of

vaccines are vital to minimize the divergence in growth that has started to take place. An

uneven global recovery is not a resilient recovery. It intensifies inequality, exacerbates

global imbalances, and heightens risks to the global economy.

Growth and monetary outlooks have diverged against the backdrop of the war, the

pandemic, as well as rising, broad based inflationary pressures. These combined factors

have impacted major currencies since the beginning of 2022. The dollar strengthened

against most major trading partners’ currencies during this period, reflecting strong U.S.

growth and rising interest rate differentials. In particular, the nominal trade-weighted

dollar had appreciated roughly 5% in the year through mid-May, though it has retraced

somewhat since. The Japanese yen depreciated roughly 11% against the dollar over this

period, largely due to widening interest rate differentials as the Bank of Japan has

maintained its highly accommodative stance that includes yield curve control measures.

Additionally, the Chinese renminbi depreciated sharply in mid-April 2022, weakening

about 6% against the dollar between end-2021 and mid-May amid portfolio capital

outflows, a darkening growth outlook, and a growing divergence in expectations for

monetary policy between China and the United States. Meanwhile, the euro has gradually

depreciated since March as Russia’s war against Ukraine has impacted the energy

landscape and raised concerns about economic activity, weakening about 8% against the

dollar since end-2021.

After being roughly stable over the past several years, global current account imbalances —

the sum of current account surpluses and deficits globally — widened due to the trade

distortions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The IMF April 2022 World Economic

2

Outlook (WEO) indicates that, at the global level, current account surpluses widened for the

second consecutive year to 1.9% of world GDP in 2021, up 0.1 percentage points from

2020. The IMF estimates that global imbalances widened further in 2021 largely because

of ongoing pandemic-related factors and elevated oil prices. The IMF expects current

account balances to remain elevated in the near term though the future path is subject to

uncertainty surrounding the pandemic, the war, and high commodity prices. Among major

U.S. trading partners, the very large surpluses of Germany, Korea, Ireland, Taiwan,

Netherlands, and Singapore have each remained significant as a share of GDP in 2021. Over

the four quarters through December 2021, Japan’s current account surplus was slightly

smaller than in 2020 as a share of GDP, but in dollar terms was comparatively high at $141

billion. China’s surplus was even higher in dollar terms at $317 billion over the same

period, remaining at elevated levels. Meanwhile, a strong U.S. policy response to the

COVID-19 pandemic, and the resulting pick-up in demand, caused the U.S. current account

deficit to rise to 3.6% of GDP in 2021. In general, and especially at a time of recovering

global growth, adjustments to reduce excessive imbalances should occur through a

symmetric rebalancing process that sustains global growth momentum rather than

through asymmetric compression of demand in deficit economies — the channel which too

often has dominated in the past.

The Biden Administration strongly opposes attempts by the United States’ trading partners

to artificially manipulate currency values to gain unfair advantage over American workers.

Treasury remains concerned by certain economies raising the scale and persistence of

foreign exchange intervention to resist appreciation of their currencies in line with

economic fundamentals. Treasury continues to press other economies to uphold the

exchange rate commitments they have made in the G-20, the G-7, and at the IMF. All G-20

members have agreed that strong fundamentals and sound policies are essential to the

stability of the international monetary system.

2

All IMF members have committed to avoid

manipulating their exchange rates to gain an unfair competitive advantage over other

members.

Nevertheless, certain economies have conducted foreign exchange market intervention in a

persistent, one-sided manner. Over the four quarters through December 2021, two major

U.S. trading partners — Singapore and Switzerland — intervened in the foreign exchange

market in a sustained, asymmetric manner to limit upward pressure on their currencies.

Treasury Analysis Under the 1988 and 2015 Legislation

This Report assesses developments in international economic and exchange rate policies

over the four quarters through December 2021. The analysis in this Report is guided by

Section 3001-3006 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (1988 Act) and

Sections 701 and 702 of the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (2015

Act) as discussed in Section 2.

2

For a list of further commitments, see the April 2021 Report on Macroeconomic and Exchange Rate Policies

of Major Trading Partners. Available at:

https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/206/April_2021_FX_Report_FINAL.pdf.

3

Under the 2015 Act, Treasury is required to assess the macroeconomic and exchange rate

policies of major trading partners of the United States for three specific criteria. Treasury

sets the benchmark and threshold for determining which countries are major trading

partners, as well as the thresholds for the three specific criteria in the 2015 Act.

In this Report, Treasury has reviewed the 20 largest U.S. trading partners

3

against the

thresholds Treasury has established for the three criteria in the 2015 Act:

(1) A significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States is a goods and services

trade surplus that is at least $15 billion.

(2) A material current account surplus is one that is at least 3% of GDP, or a surplus for

which Treasury estimates there is a current account “gap” of at least 1 percentage point

of GDP using Treasury’s Global Exchange Rate Assessment Framework (GERAF).

Current account gaps are defined in this Report as the deviation of a given current

account balance — stripping out cyclical factors — from an estimated optimal current

account balance given the economy’s economic fundamentals and the appropriate mix

of macroeconomic policies.

(3) Persistent, one-sided intervention occurs when net purchases of foreign currency

are conducted repeatedly, in at least 8 out of 12 months, and these net purchases total

at least 2% of an economy’s GDP over a 12-month period.

4

In accordance with the 1988 Act, Treasury has also evaluated in this Report whether

trading partners have manipulated the rate of exchange between their currency and the

United States dollar for purposes of preventing effective balance of payments adjustments

or gaining unfair competitive advantage in international trade.

Because the standards in the 1988 Act and the 2015 Act are distinct, a trading partner

could be found to meet the standards identified in one of the statutes without necessarily

being found to meet the standards identified in the other. Section 2 provides further

discussion of the distinctions between the 1988 Act and the 2015 Act.

Treasury Conclusions Related to the 2015 Act

Switzerland has exceeded the thresholds for all three criteria over the four quarters

through December 2021, and therefore Treasury is conducting enhanced analysis of

Switzerland’s macroeconomic and exchange rate policies in this Report. Switzerland had

previously exceeded the thresholds for only two of the three criteria under the 2015 Act

over the four quarters through June 2021 as noted in the December 2021 Report, in which

Treasury conducted an in-depth analysis of Switzerland. Previous to that, Switzerland

exceeded the thresholds for all three criteria under the 2015 Act, as noted in the April 2021

and December 2020 Reports, in each of which Treasury conducted an enhanced analysis of

Switzerland. Since Switzerland has again exceeded the thresholds for all three criteria,

3

Based on total bilateral trade in goods and services (i.e., imports plus exports).

4

These quantitative thresholds for the scale and persistence of intervention are considered sufficient on their

own to meet the criterion. Other patterns of intervention, with lesser amounts or less frequent interventions,

might also meet the criterion depending on the circumstances of the intervention.

4

Treasury will continue its enhanced bilateral engagement with Switzerland, which

commenced in early 2021, to discuss the Swiss authorities’ policy options to address the

underlying causes of its external imbalances.

Both Vietnam and Taiwan exceeded the thresholds of fewer than three criteria over the

four quarters through December 2021. Vietnam had previously exceeded the thresholds

for all three criteria as noted in the December 2021, April 2021, and December 2020

Reports, in each of which Treasury conducted enhanced analysis of Vietnam. Taiwan had

previously exceeded the thresholds for all three criteria as noted in the December 2021

and April 2021 Reports, in each of which Treasury conducted enhanced analysis of Taiwan.

Though Vietnam and Taiwan no longer meet all three criteria for enhanced analysis,

Treasury will continue to conduct an in-depth analysis of these economies’ macroeconomic

and exchange rate policies until they do not meet all three criteria under the 2015 Act for at

least two consecutive Reports.

In early 2021, Treasury commenced enhanced bilateral engagement with Vietnam in

accordance with the 2015 Act. As a result of discussions through the enhanced

engagement process, Treasury and the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) reached agreement in

July 2021 to address Treasury’s concerns about Vietnam’s currency practices.

5

Treasury

continues to engage closely with the SBV to monitor Vietnam’s progress in addressing

Treasury’s concerns and is thus far satisfied with progress made by Vietnam.

In May 2021, Treasury commenced enhanced bilateral engagement with Taiwan in

accordance with the 2015 Act. These productive discussions have helped develop a

common understanding of the policy issues related to Treasury’s concerns about Taiwan’s

currency practices. Treasury continues to engage closely with Taiwan’s authorities.

Treasury Assessments of Other Major Trading Partners

Treasury has found in this Report that no major trading partner other than Switzerland

met all three criteria under the 2015 Act during the four quarters ending December 2021.

Treasury has also established a Monitoring List of major trading partners that merit close

attention to their currency practices and macroeconomic policies. An economy meeting

two of the three criteria in the 2015 Act is placed on the Monitoring List. Once on the

Monitoring List, an economy will remain there for at least two consecutive Reports to help

ensure that any improvement in performance versus the criteria is durable and is not due

to temporary factors. As a further measure, Treasury will add and retain on the Monitoring

List any major U.S. trading partner that accounts for a large and disproportionate share of

the overall U.S. trade deficit even if that economy has not met two of the three criteria from

the 2015 Act. In this Report, the Monitoring List comprises China, Japan, Korea,

Germany, Italy, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Mexico.

5

See “Joint Statement from the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the State Bank of Vietnam.” Available at:

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0280.

5

All except Taiwan and Vietnam (which were subject to enhanced engagement) were

on the Monitoring List in the December 2021 Report.

Ireland has been removed from the Monitoring List in this Report, having met only one out

of three criteria – a material current account surplus – for two consecutive Reports.

China’s economy faces downside risks, primarily due to a surge in COVID-19 cases in early

2022 that has led to an acceleration of lockdowns of major cities and generated further

uncertainty and supply chain disruptions. China’s failure to publish foreign exchange

intervention and broader lack of transparency around key features of its exchange rate

mechanism make it an outlier among major economies, and the activities of China’s state-

owned banks in particular warrant Treasury’s close monitoring.

Treasury Conclusions Related to the 1988 Act

The 1988 Act requires Treasury to consider whether any economy manipulates the rate of

exchange between its currency and the U.S. dollar for purposes of preventing effective

balance of payments adjustments or gaining unfair competitive advantage in international

trade. In this Report, Treasury has concluded that no major trading partner of the

United States engaged in conduct of the kind described in Section 3004 of the 1988

Act during the relevant period. This determination has taken account of a broad range of

factors, including not only trade and current account imbalances and foreign exchange

intervention (the 2015 Act criteria), but also currency developments, exchange rate

practices, foreign exchange reserve coverage, capital controls, and monetary policy.

Treasury continues to carefully track the foreign exchange and macroeconomic policies of

U.S. trading partners under the requirements of both the 1988 Act and the 2015 Act, and to

review the appropriate metrics for assessing how policies contribute to currency

misalignments and global imbalances. The Administration has strongly advocated for our

major trading partners to carefully calibrate policy tools to support a strong and

sustainable global recovery. Treasury also continues to stress the importance of all

economies publishing data related to external balances, foreign exchange reserves, and

intervention in a timely and transparent fashion.

6

Section 1: Global Economic and External Developments

This Report covers economic, trade, and exchange rate developments in the United States,

the global economy, and the 20 largest trading partners of the United States for the four

quarters through December 2021 and, where monthly data are available, through end-

April 2022 and, where quarterly data are available, through end-March 2022. Total goods

and services trade of the economies covered with the United States amounted to more than

$4.6 trillion in the four quarters through December 2021, almost 80% of all U.S. trade

during that period.

U.S. Economic Trends

Gross domestic product (GDP) in United States recovered to, and surpassed pre-pandemic

economic activity in 2021, supported by federal financial assistance, healthy household

balance sheets, favorable financial conditions, and mass distribution of vaccines—even as

more contagious coronavirus variants emerged, and supply-chains were strained. As a

result, real GDP rose 5.5% over the four quarters of 2021—marking the fastest annual pace

of growth in 37 years—while firms added 6.7 million new jobs, the most jobs created in a

single year on record. At the same time, inflation accelerated throughout 2021: as

measured by the consumer price index (CPI), the 12-month change in prices was 7.1% in

December 2021 as demand recovered faster than supply during the year.

In the first quarter of 2022, real GDP declined 1.5% at an annual rate, according to the

advance (first) estimate. This reflected a much slower inventory build, a surge in imports,

and declines in government spending at all levels. Nonetheless, demand by households and

businesses strengthened growth in final private domestic purchases accelerated to a

healthy 3.7% rate. Firms added another 2.1 million jobs in the first four months of the

year, and the unemployment rate (U-3) was 3.6% in April, only 0.1 percentage points above

the five-decade low just before the pandemic. Moreover, the prime-age (ages 25 to 54)

labor force participation rate (LFPR) has increased by a net 0.5 percentage points in the

first four months of 2022. Meanwhile inflation further accelerated in the first four months:

inflation as measured by the personal consumption price index—the Federal Reserve’s

preferred measure was up 6.3% over the year ending April 2022. However, year-on-year

inflation is likely to slow in the coming months as monthly rates moderate relative to year-

earlier rates and monetary policy accommodation is expeditiously removed.

Despite a decline in real GDP during this year’s first quarter, the outlook for 2022 as a

whole remains positive—though risks to the outlook remain, particularly uncertainty

related to the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine, continued supply chain disruptions due

to COVID-19 lockdowns in Asia, and rising interest rates. As of May, private forecasters

project real GDP to grow 1.5% over the four quarters of 2022.

Economic Performance in 2021

Economic activity in 2021 was marked by two distinct patterns of growth in each half of

the year. The first half of 2021 was noteworthy for the development and distribution of

7

vaccines, as well as the disbursement of additional pandemic aid packages—the COVID-

Related Tax Relief Act of 2020 and the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act. These packages

secured additional funding to address COVID-19 infections and vaccinate the population,

ensured financial security for low- and middle-income households, and provided liquidity

for small businesses as well as state, local, and tribal governments. In addition, consumers’

assessments of the near-term outlook improved and businesses reopened, even as inflation

continued to accelerate. As a result, real GDP surged by 6.5% during the first half of the

year—the strongest half-year pace since 1984, notwithstanding the unprecedented pace

seen in the initial post-shutdown recovery—and by the end of the second quarter of 2021,

real GDP rose above its pre-pandemic level.

The second half of the year was marked by the winding down of fiscal support as well as

the emergence of two new COVID-19 variants (Delta and Omicron) that increased

disruptions to supply chains and boosted inflation. Real GDP growth slowed to a still-brisk

pace of 4.6% at an annual rate during the latter half of 2021, with much of the growth due

to the rebuilding of inventories as private domestic final demand—that is, household

consumption, business fixed investment, and residential investment—grew more slowly.

Real growth in private domestic final demand (PDFD) slowed to 2.0% at an annual rate

during the second half of 2021, after jumping by 11.0% in the first half. All categories of

PDFD showed slower or negative growth in the second half of 2021. Real personal

consumption expenditures increased by 2.2% during the second half of 2021, a

considerably slower pace than the stimulus-boosted 11.7% jump during the first half of the

year, as real PCE was close to pre-pandemic trend. Business fixed investment (BFI)

similarly slowed, gaining just 2.3% in the latter half of 2021 after rising 11.1% in the first

half. The slower growth of BFI was primarily due to a drop in in structures investment

(-6.2%) as well as a minimal increase in spending on equipment (0.2%). Investment in

intellectual property product also slowed (9.0%), but less drastically than the other two

categories of BFI. Residential investment was the one category of PDFD to outright

decrease; it declined 2.9% during the second half of 2021, after a flat reading during the

first half. Nevertheless, both residential investment and business equipment investment

remain well ahead of pre-pandemic trend.

Meanwhile, private inventory accumulation turned positive in the third quarter of 2021,

due to a reduced drawdown in inventories, and the contribution increased in the final

quarter of the year as firms began to rebuild inventories. In the two quarters combined,

the change in private inventories added an average 3.8 percentage points to GDP growth in

the latter half of 2021, after subtracting 1.9% points in the first two quarters of 2021.

The remaining major components of GDP subtracted from economic growth in the second

half of 2021. The impulse from total government spending turned negative as federal

pandemic programs waned—particularly the Paycheck Protection Program, which ceased

purchasing services from financial institutions to service small business loans. Total

government consumption and investment declined 0.9% after rising by 1.1% during the

first half. Meanwhile, the contribution of net exports to real GDP growth remained

modestly negative in the second half of 2021—though less so than in the first. Net exports

8

subtracted an average 0.7 percentage points from GDP growth in the second half of 2021,

after being a 0.9% drag on growth in the first. Although growth of exports turned strongly

positive in the fourth quarter, the contribution was offset by a third quarter decline in

exports as well as strong domestic demand for foreign goods and services. The continued

rise in imports in the second half of 2021 was likely driven by inventory restocking and

continued strong domestic demand for foreign goods.

The labor market recovery was consistently solid throughout 2021, and the pace of job

creation picked up a bit during the latter half of the year. Payroll job creation averaged

534,000 per month during the first half of 2021, then accelerated somewhat to 590,000 per

month during the second half. By December 2021, a total of 6.7 million jobs had been

added over the year, and the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.9%, or 2.8 percentage

points lower than the December 2020 level, the fastest calendar year decline in the

unemployment rate on record. Improvement in the LFPR was slower than in payrolls or

the unemployment rate, but some progress was made by the end of 2021. The overall

LFPR was range-bound between 61.4% and 61.7% during the first half of last year, as a

sizeable 0.7 percentage point increase in the prime-age LFPR was offset by stable or

negative changes in LFPRs for non-prime age cohorts. However, total LFPR resumed

recovery in the last two months of 2021, rising to 61.9%—though still 1.5 percentage

points below the high of 63.4% in early 2020—driven in part by a 0.2 percentage point gain

in the prime-age LFPR to 81.9%, which was 1.2 percentage points below the January 2020

high of 83.1%.

Inflation began picking up early in 2021. Throughout the year, many factors helped drive

prices higher, including a slow recovery in global energy production, supply-chain

disruptions and related shortages of specific inputs, persistently strong demand for

durable goods, rising costs of food supply-chain inputs, brisk growth in house prices, and

increased demand for pandemic-sensitive services (such as travel, leisure, and hospitality)

as the economy reopened. Although inflation eased modestly in the third quarter, it again

accelerated by the end of the year. Over the year through December 2021, the headline

consumer price index CPI rose by 7.1% reflecting in part a nearly 50% jump in gasoline

prices and a 6.3% increase in the food CPI. In addition, growth in the CPI for core goods

and services rose by 5.5% over the year through December 2021, boosted by soaring prices

for new and used motor vehicles—with yearly gains of 11.8% and 37.3%, respectively—

and a 4.1% jump in the shelter index over the same period.

Economic Developments Since December 2021

Real GDP growth declined by 1.5% at an annual rate in the first quarter of 2022, reflecting a

much slower inventory build, a larger drag from net exports, and declines in government

spending at all levels. However, real growth in PDFD accelerated during the first quarter to

3.9% at an annual rate. Among its components, real PCE grew 3.1%, as growth in spending

on services accelerated to 4.8%, offsetting a flat reading in consumption of goods. Business

fixed investment jumped 9.2% at an annual rate in the first quarter. Although investment

in structures declined 3.6% and posed a small drag, equipment investment surged by

13.2% and spending on intellectual property products grew by 11.6%. Private residential

9

investment grew by 0.4%. Despite healthy activity in much of the domestic economy,

slower growth in inventories during the first quarter subtracted 1.1 percentage points

from real GDP, and the widening of the trade deficit, due to surging imports and weaker

demand for U.S. exports pared 3.2 percentage points from growth. Real government

spending declined 2.7% at an annual rate in the first quarter, partly reflecting a decline in

federal expenditures as well as surging construction prices for state and local governments

which has lowered real investment.

Labor markets remained tight in the early months of 2022. Firms added 2.1 million jobs

during the first four months of the year, and the unemployment rate (U-3) was 3.6% in

April, only 0.1 percentage points above the five-decade low just before the pandemic. The

primary source of labor supply has recovered moderately in recent months: the prime-age

LFPR has risen by 0.5 percentage points so far this year. At 82.4%, the prime-age LFPR was

just 0.6 percentage points below pre-pandemic levels. Some alternative measures of labor

market tightness are even outperforming 2019 levels, suggesting markets are even tighter

than before the pandemic, which has pushed up wage growth—particularly in lower-wage

industries. Since August 2021, the ratio of job-openings to unemployed has held at a

historically low rate, such that there are roughly two job openings per unemployed

person—a ratio even below that seen in 2019. Similarly, the quits rate has risen to a

historically high level of 3.0% of the labor force, or 0.6 percentage points above previous

peak set in 2019.

Inflationary pressures accelerated during the first few months of 2022. Over the year

ending April 2022, inflation as measured by the CPI was 8.3%. The food price index was up

9.4% over the twelve months through April 2022, and the energy index rose 30.3% over

the same period. The core CPI inflation was 6.2% over the year through April and is

becoming increasingly broad-based. Inflation from shelter has been rising at a rapid clip on

a monthly basis, and over the year through April, reached 5.1%. The Federal Reserve’s

preferred measure of inflation, the PCE price index, has shown a similar pattern of

acceleration as compared with the CPI (headline rate of 6.3% over the year through April)

but prints at a slower rate due to differences in computation. The PCE measure is

reweighted monthly and shows substitution effects, whereas the CPI measure is

reweighted every two years and does not adjust for substitution of lower-priced products.

Although headline and core inflation by both measures have started to slow on a year-over-

year basis, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and COVID-related shutdowns in China present

upside risk to the inflation outlook as they will elevate energy prices, which are likely to

feed through to food prices as agricultural supply-chains rely on diesel and natural gas.

Moreover, shutdowns in China are likely to lengthen the duration of supply-chain

disruptions, keeping inventories lean and prices elevated.

Federal Finances

The federal government’s deficit and debt were trending higher before the pandemic but

rose sharply as a result of the various fiscal responses to combat the pandemic’s effect on

the economy.

10

At the end of FY 2021, the federal government’s budget deficit was $2.78 trillion (12.4% of

GDP), declining from $3.13 trillion (15.0% of GDP) at the end of FY 2020 but still $1.79

trillion higher than in FY 2019. Federal receipts totaled $4.05 trillion in FY 2021, up $626

billion (18.3%) from FY 2020. Net outlays for FY 2021 were $6.82 trillion, up $266 billion

(4.1%) from FY 2020, primarily due to the fiscal aid measures enacted in late 2020 and

early 2021. At the end of FY 2021, gross federal debt was $28.4 trillion, up from $26.9

trillion at the end of FY 2020. Federal debt held by the public, which includes debt held by

the Federal Reserve but excludes federal debt held by government agencies, rose from

$21.0 trillion at the end of FY 2020 (100.3% of GDP) to $22.3 trillion by the end of FY 2021

(99.7% of GDP).

Federal finances have improved thus far in FY 2022 as federal fiscal aid programs have

wound down. In the first seven months of FY 2022, the federal deficit totaled $0.36 trillion,

down from $1.93 trillion in the comparable period in FY 2021. Receipts for the fiscal year

to date are $0.84 trillion higher than last year, while outlays are $0.73 trillion lower. At the

end of April 2022, gross federal debt stood at $30.4 trillion while debt held by the public

was $23.8 trillion.

U.S. Current Account and Trade Balances

The current account deficit

rose in the second half of

2021 to 3.7% of GDP, up 0.3

percentage point from the

previous half. This was the

largest deficit as a share of

GDP since the end of 2008. In

the second half of 2021, the

goods deficit increased while

services and income

surpluses fell. From 2013 to

2020, the headline U.S.

current account deficit had

been quite stable, around 2-

2.5% of GDP.

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

H1 2013

H2 2013

H1 2014

H2 2014

H1 2015

H2 2015

H1 2016

H2 2016

H1 2017

H2 2017

H1 2018

H2 2018

H1 2019

H2 2019

H1 2020

H2 2020

H1 2021

H2 2021

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Percent of GDP

U.S. Current Account Balance

Goods Services Income Current Account Balance

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Haver

11

While U.S. domestic

demand recovered

quickly, demand in the

rest of the world did so

more moderately,

resulting in a widening

trade deficit – both in

nominal terms and as a

share of GDP. Steep

goods trade recovery,

with both exports and

imports back to pre-

pandemic levels in 2021,

reflected control over the pandemic and robust fiscal policy that boosted economic output.

The U.S. goods and services trade deficit was 3.8% of GDP in the second half of 2021,

slightly wider than in the first half of 2021, as growth in U.S. imports of both goods and

services outpaced export growth.

At the end of 2021, the U.S. net international investment position marked a net liability of

$18.1 trillion (a record 75% of GDP), a deterioration of $2.2 trillion compared to first half of

2021. The value of U.S.-owned foreign assets was $35.2 trillion, while the value of foreign-

owned U.S. assets stood at $53.3 trillion. Deterioration in the net position was due in part

to the outperformance of U.S. equity markets relative to global peers.

International Economic Trends

Following a steep contraction of the global economy in 2020, global output grew 6.1% in

2021 according to the IMF as real GDP in most advanced economies recovered to pre-

pandemic levels of output. In contrast, many emerging markets and developing economies

have faltered in regaining their footing back to their pre-pandemic trajectories both in

terms of output and labor market recovery. The recovery was most pronounced in

economies that undertook strong policy support and where large shares of the population

have been vaccinated—though the Delta and Omicron variants complicated the full

resumption in economic activity for most. In addition, much of the world is contending

with elevated inflation rates due to faster-than-expected demand growth and supply chain

disruptions. As inflation has accelerated, some governments have been left with tough

policy decisions on whether to support the recovery or stem rising prices. Select countries,

most notably in the Asia-Pacific region, have not seen inflation accelerate as much as the

rest of the world as renewed COVID-19 cases and lockdowns continue to drag down their

economies. These factors – rising inflation, available scope and efficiency of policy support,

containment of the virus, and pre-existing vulnerabilities – all form countries’ unique

economic contexts and risks contributing to further inequality within and across countries.

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

Jan-2006

Jan-2007

Jan-2008

Jan-2009

Jan-2010

Jan-2011

Jan-2012

Jan-2013

Jan-2014

Jan-2015

Jan-2016

Jan-2017

Jan-2018

Jan-2019

Jan-2020

Jan-2021

Jan-2022

Annual Percent Change

U.S. Goods and Services Trade Growth

Exports Imports

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

12

The IMF projects global economic growth will slow in 2022 to 3.6% primarily as a result of

Russia’s war against Ukraine and continued outbreaks of COVID-19. In addition to the

tremendous human cost of Russia’s war and the devastation it is having on the Ukrainian

economy, regional and global spillovers are significant. Trade disruptions and rising

commodity prices are boosting inflation and increasing food insecurity. Downside risks to

the outlook include a potential acceleration of the war, as well as further COVID-related

lockdowns in China and potential new variants. Given this additional uncertainty,

countries should balance targeted policy responses where possible, with keeping medium-

term inflation expectations anchored. Countries that still have low vaccination uptake and

high COVID-19 case loads should prioritize health measures and maintain fiscal, monetary,

and macroprudential support policies where there is policy space and is warranted by

macroeconomic conditions.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

India

China

Taiwan

Mexico

Brazil

Malaysia

Vietnam

Thailand

2021 2022 (Projected)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Ireland

Singapore

UK

France

Italy

Belgium

US

Netherlands

Canada

Korea

Switzerland

Germany

Japan

Annual Percent Change

Real GDP Growth

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2022

Advanced Economies

Emerging Market Economies

13

Foreign Exchange Markets

6

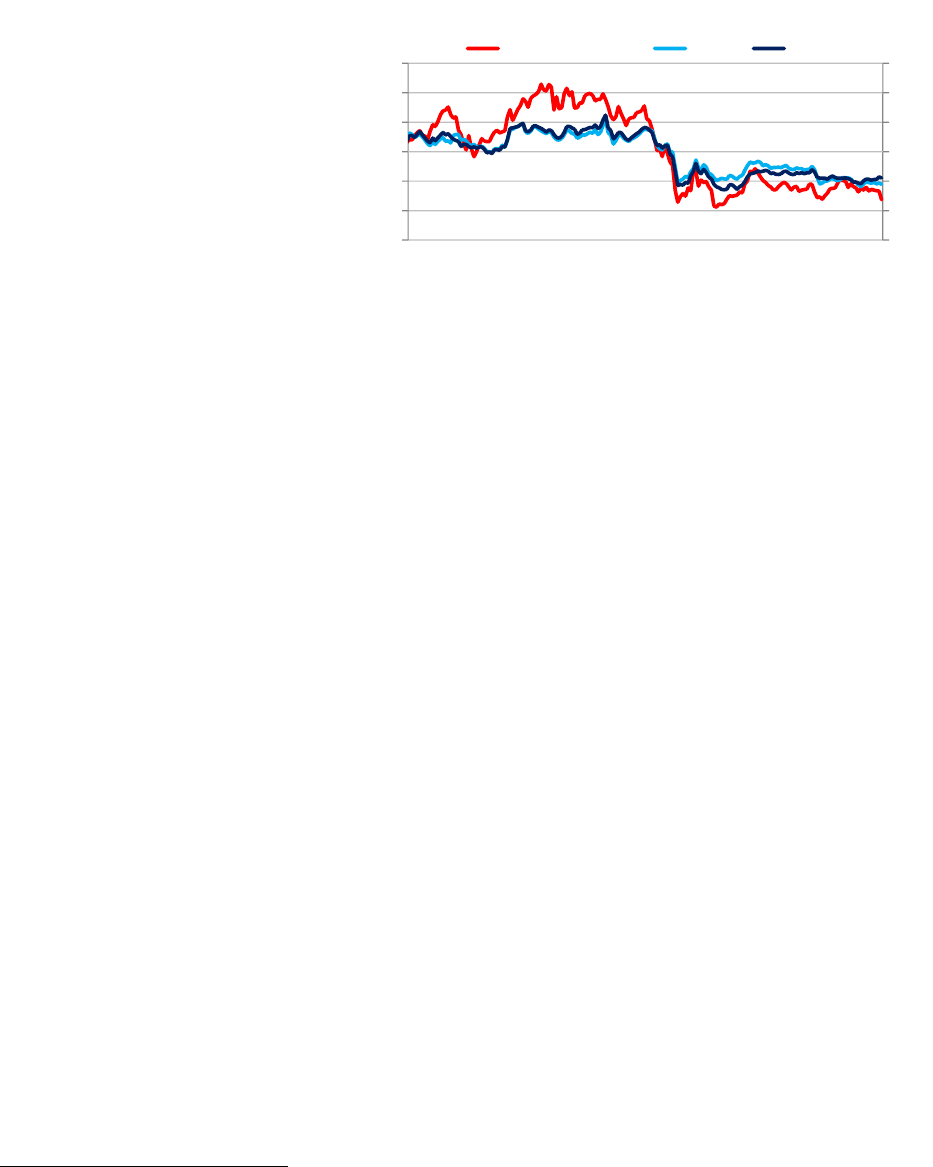

Even against the backdrop of

geopolitical shocks and monetary

tightening, capital outflows from

emerging markets and currency

valuation fluctuations remained

relatively orderly and subdued. The

nominal trade-weighted dollar

strengthened moderately by 7.3%

from the end of December 2020 to

end April 2022. The dollar

appreciated by 11.2 % against the

currencies of other major advanced

economies over this period, most

notably against the euro and the

Japanese yen. In contrast, the dollar

appreciated by only 3.7% against

major emerging economies’

currencies. Since the end of

December 2020, the dollar

depreciated against the Brazilian

real the most of all major trading

partners’ currencies; after a

dramatic decline in Brazilian real

value in the second half of 2021, it

retraced much of its value this year

to date.

In the first half of 2021, the nominal trade weighted dollar strengthened by 1.2%. The

upward climb of the dollar continued into the second half of 2021 by 2.4% though there

were smaller downward movements against the Swiss franc, Chinese renminbi, Vietnamese

dong, and the New Taiwan Dollar. Between end-2021 and end-April 2022, among U.S.

major trading partner currencies, the dollar has depreciated against the Brazilian real and

to a lesser extent, against the Mexican peso, while appreciating against all other major

trading partners’ currencies. The Brazilian real has benefited from rising commodities

prices and from interest rate hikes. During this period, the dollar has appreciated most

significantly against the Japanese yen and Taiwanese dollar.

6

Unless otherwise noted, this Report quotes exchange rate movements using end-of-period data. Bilateral

movements against the dollar and the nominal effective dollar index are calculated using daily frequency or

end-of-period monthly data from the Federal Reserve Board. Movements in the real effective exchange rate

for the dollar are calculated using monthly frequency data from the Federal Reserve Board, and the real

effective exchange rate for all other currencies in this Report is calculated using monthly frequency data from

the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) or JP Morgan if BIS data are unavailable.

Emerging Market Economies (EME)

-20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 25

EME basket

Brazil

China

Vietnam

Mexico

Singapore

Taiwan

India

Malaysia

Thailand

Advanced Foreign Economies (AFE)

-20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 25

2021 H1 2021 H2 2022 H1 (through end Apr) Net change

U.S. Dollar vs. Major Trading Partner Currencies

(+ denotes dollar appreciation)

Contribution to percent change relative to end-Dec 2020

Broad dollar index

Sources: FRB, Haver

-20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 25

AFE basket

Canada

UK

Switzerland

Euro

Japan

14

On a real effective basis, the dollar appreciated 7.2% from end-December 2020 to end-April

2022. The real broad dollar is almost 9% above its 20-year average as of end-April 2022.

The IMF continues to judge the dollar to be overvalued on a real effective exchange rate

basis. Meanwhile, the real effective exchange rates of several surplus economies that the

IMF assessed to be undervalued in 2020 have adjusted minimally or depreciated through

April 2022, relative to the 2020 average (e.g., Germany, Malaysia, and Thailand). However,

these adjustments only provide partial information about current exchange rate

misalignments.

Global Imbalances

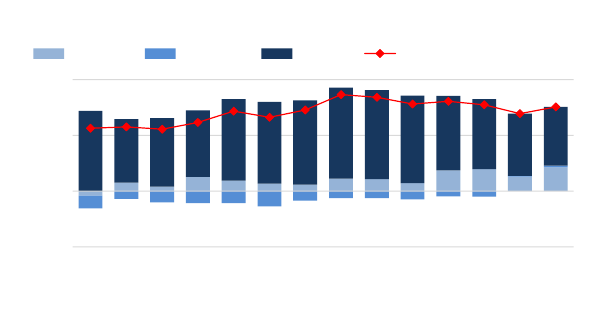

Global current account imbalances were broadly stable in the few years prior to the

pandemic. The IMF April 2022 WEO indicates that, at the global level, current account

surpluses widened for the second consecutive year to 1.9% of world GDP in 2021, up 0.1

percentage points from 2020, with the latest estimates of excessive current account

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

U.K.

United States

Canada

Brazil

Australia

India

Mexico

Belgium

Switzerland

Netherlands

Korea

Italy

Ireland

Euro Area

Singapore

Vietnam

Thailand

Germany

Malaysia

Japan

Percent

2020 REER Gap Assessment (mid)¹ Adjustments as of Apr-2022²

CA Surplus Economies

CA Deficit Economies³

IMF Estimates of Exchange Rate Valuation and Recent Developments

Undervalued

Overvalued

Sources: IMF 2021 External Sector Report, IMF 2021 Article IV Consultation Staff Report for Ireland, IMF 2020 Article IV Consultation Staff

Report for Vietnam, BIS REER Indices, JP Morgan, FRB

1/The IMF's estimate of real effective exchange rate (REER) gap (expressed as a range) compares the country's average REER in 2020 to

the level consistent with the country's medium-term economic fundamentals and desired policies. The midpoint of the gap range is

depicted above. REER gap for Vietnam uses 2019 REER Gap.

2/Change between 2020 average REER and end-April 2022. Because the REER level consistent with the country’s medium-term economic

fundamentals and desired policies changes over time, these adjustments provide partial information about current exchange rate

misalignments.

3/Economies sorted based on whether they were more frequently in deficit or surplus over the past five years.

Note: The IMF does not provide an estimate of Taiwan's REER gap.

15

surpluses and deficits at 1.2%

of world GDP in 2020.

7

The

efforts to contain the COVID-

19 virus and its effects led to

extraordinary policy

responses that continue to

influence global trade and

shifts in saving and

investment, and are driving

increases in global

imbalances.

Supply demand imbalances

were especially problematic

in the past year as the

pandemic came under control in many parts of the world while other countries continued

to intermittently lock down. A stronger recovery in advanced economies, especially in the

United States, created external demand that has fueled the recovery in many emerging and

developing economies.

External stock positions

widened to a historical peak

in 2020. The IMF estimates

that this was due to changes

in net foreign asset positions

that were larger than

explained by current account

balances in a number of

cases, reflecting large

valuation changes, including

those driven by asset price

and currency movements.

Since then, stocks of foreign

assets and liabilities have

decreased but still remain at

historic highs.

7

See the Annex of this Report for a more detailed discussion of when current account surpluses and deficits

may be considered excessive and the evolution and drivers of global current account surpluses and deficits

over time.

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

Percent of Global GDP

Global Current Account Imbalances

China Germany Japan

Other Surplus United States Other Deficit

Statistical Discrepancy

Sources: IMF WEO, Haver

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Percent of Global GDP

International Investment Positions

China Germany Japan

Other Surplus United States Other Deficit

Note: The difference between aggregate creditor and debtor positions reflect

any missing country-level data, as well as the global statistical discrepancy.

Sources: IMF, Central Bank of China (Taiwan)

16

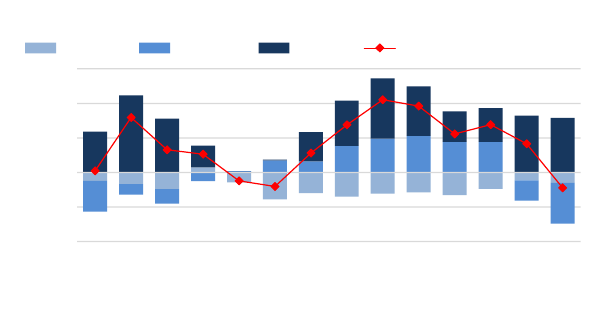

Capital Flows to Emerging Market Economies

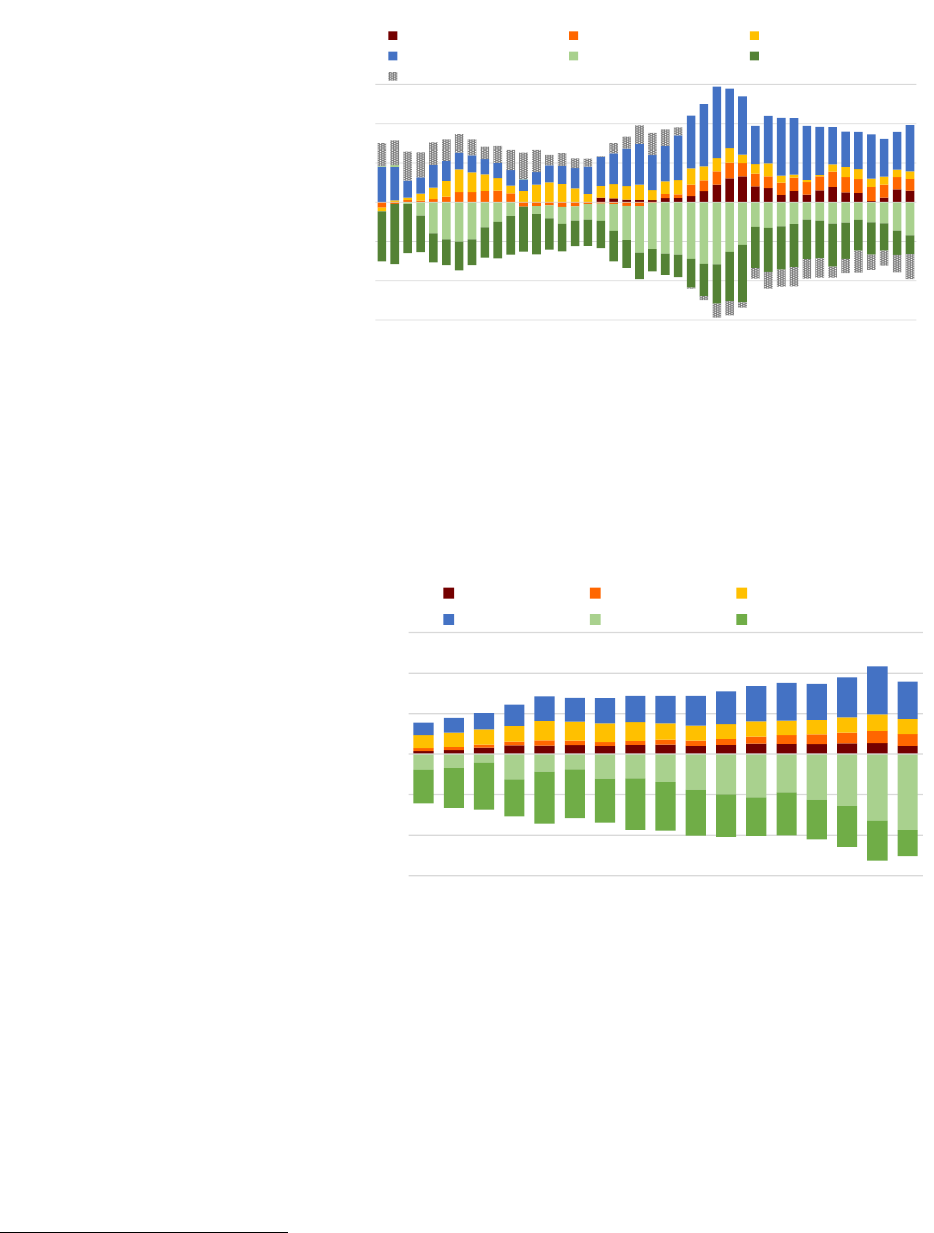

Net capital flows to emerging

market economies remained

mixed during 2021. Over the

four quarters through

December 2021, net outflows

of portfolio and other

investment totaled $357

billion, just $25 billion less

than the same period in 2020.

Throughout the year,

nonresident net flows

remained positive, suggesting

that foreign investor demand

for emerging market

economy assets recovered as

the global economic recovery

took hold, but were offset by

resident net outflows. On a

cumulative basis since the

onset of the pandemic, net

portfolio flows have

continued to decline further,

reaching roughly $500 billion

below pre-pandemic levels.

Excluding China, net outflows

of portfolio investment to

emerging markets have been

more pronounced, with a

cumulative decline of $644

billion compared to pre-

pandemic levels.

On balance, total net capital flows continued their recovery over the first three quarters of

2021. Continued robust foreign direct investment, along with decelerating outflows of

other investment, kept net flows relatively buoyant over the first half of the year. Net other

investment flows further accelerated this rebound in capital flows during the third quarter.

During this time, net portfolio outflows remained persistent and driven by net resident

outflows.

8

Since then, net other investment outflows resumed in the fourth quarter of

2021, weighing on net aggregate flows along with accelerating net portfolio outflows. Amid

nascent signs of tightening global financial conditions, these combined net outflows

8

In particular, large resident portfolio outflows from China in the first quarter of 2021 totaled more than $70

billion. Resident portfolio outflows from China have since decelerated but continued during the rest of the

year, in line with the broader trend of net resident portfolio flows since 2014.

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

t t+1 t+2 t+3 t+4 t+5 t+6 t+7 t+8

USD Billions

Time since onset (quarters)

Global Financial Crisis (2008) Taper Tantrum (2013)

RMB Devaluation (2015) EM Selloff (2018)

COVID Sudden Stop (2020)

Note: Depicts net resident and nonresident portfolio investment flows on a cumulative basis

following particular shock episodes. 2021 reflects data through the end-December where

available.

Source: National Authorities, U.S. Department of the Treasury Staff Calculations

Capital Outflows

Capital Inflows

Cumulative Portfolio Flows to Emerging Markets

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

400

Q4-08 Q4-10 Q4-12 Q4-14 Q4-16 Q4-18 Q4-20

USD Billions

Net Capital Flows to Emerging Markets

Financial Derivatives (Net) Other Investment (Net)

Direct Investment (Net) Portfolio Investment (Net)

Net Capital Flows (excl reserves)

Note: Financial account (excluding reserves) adjusted for errors and ommissions.

2021 reflects data through the end-December where available.

Source: National Authorities, U.S. Department of the Treasury Staff Calculations

Capital Outflows

Capital Inflows

17

reached $145 billion over the fourth quarter, approaching levels last seen in early 2021 and

early 2020.

Higher frequency data (from sources beyond quarterly balance of payments data) suggest

that, since end-2021, nonresident portfolio flows to emerging markets continue to be

mixed and remain relatively volatile. Monetary policy tightening brought about from

rising, broad based inflationary pressures, geopolitical uncertainty brought on by Russia’s

war against Ukraine, and an expected slowdown in global growth have all contributed to

tightening financial conditions across emerging market economies. Net foreign portfolio

flows collapsed after Russia’s invasion — with the speed and scale of cumulative outflows

during the early weeks of the war matching the March 2020 COVID-19 selloff — but have

since leveled off. These data also suggest that nonresident portfolio outflows from China

may have reached record highs in March 2022 driven by these same factors, along with a

worsening outlook for China’s economy amid tightening lockdown measures.

Foreign Exchange Reserves

Global foreign currency reserves increased by $231 billion over the four quarters through

December 2021, reaching $12.9 trillion. Estimated net purchases of $516 billion in foreign

exchange were offset partly by a $301 billion decline due to valuation effects from dollar

appreciation over the year. Meanwhile, estimated interest income contributed minimally

to the rise in reserves.

Although there is no single commonly accepted standard for assessing reserve adequacy,

Treasury assess that the economies covered in this Report continue to maintain ample—or

more than ample—foreign currency reserves compared to standard adequacy benchmarks.

Reserves in most of these economies are more than sufficient to cover short-term external

liabilities and anticipated import costs. Moreover, the most recent IMF assessments of

adequacy based on composite metrics across emerging market economies for 2020 suggest

reserves are broadly adequate.

Credible and effective macroeconomic policy frameworks, rather than intervention to

accumulate reserves beyond adequate levels, should serve to buffer external shocks. This

is particularly relevant for economies with other reserve-like resources such as swap lines,

sovereign wealth funds, and credit lines from international financial institutions that can

18

serve as additional buffers. Moreover, foreign exchange intervention should not substitute

for warranted macroeconomic adjustment.

Economic Developments in Selected Major Trading Partners

China

China’s economy continued to recover from the pandemic in 2021, with real GDP

increasing 8.1% year-on-year, but economic activity slowed in the latter half of 2021 due to

property sector stress and energy supply disruptions. Private consumption remains weak,

reflecting poor consumer confidence amid slowing growth momentum, periodic large-scale

lockdowns to curb the spread of COVID-19, and other pandemic-related uncertainty.

Subdued private consumption also reflects the unbalanced nature of China’s

macroeconomic policy response to the pandemic, which has favored infrastructure

investment and support for firms rather than direct support to households. In 2021, the

authorities significantly tightened their fiscal stance and moderately tightened monetary

FX Reserves

(USD Bns)

1Y Δ FX

Reserves

(USD Bns)

FX Reserves

(% of GDP)

FX Reserves

(% of ST debt)

FX Reserves

(% of IMF ARA

Metric)*

China 3,250.2 33.6 18% 238% 120%

Japan 1,283.3 -29.5 26% 41% ..

Switzerland 1,033.8 20.6 127% 81% ..

India 569.9 27.7 18% 497% 191%

Taiwan 548.4 18.5 71% 278% ..

Korea 438.3 8.2 24% 264% 99%

Singapore 408.3 48.9 103% 33% ..

Brazil 330.9 -11.8 21% 420% 164%

Thailand 224.8 -21.2 44% 357% 251%

Mexico 180.8 -3.4 14% 364% 129%

UK 127.8 -11.8 4% 2% ..

Malaysia 107.2 4.5 29% 114% 118%

Vietnam 107.4 13.0 30% 338% ..

Canada 78.1 1.3 4% 8% ..

France 53.6 -1.5 2% 2% ..

Italy 48.6 2.0 2% 4% ..

Australia 37.4 5.3 2% 9% ..

Germany 37.0 0.1 1% 1% ..

Belgium 11.2 0.2 2% 2% ..

Netherlands 5.3 -0.6 1% 1% ..

Ireland 5.9 0.9 1% 1% ..

United States 40.7 -3.8 0% 1% ..

World 12,915.2 218.4 n.a. n.a. ..

Foreign exchange reserves as of end-December 2021.

GDP caluclated as sum of rolling 4Q GDP through Q4-2021.

Table 1: Foreign Exchange Reserves

Sources: National Authorities, World Bank, IMF, BIS.

* IMF Assessing Reserve Adequacy Metric, a composite measure of reserve adequacy, as of end-2020.

China's reserves are compared to the IMF's capital controls-adjusted metric. The IMF assesses reserves

between 100-150% of the ARA metric to be adequate.

Short-term debt consists of gross external debt with original maturity of one year or less, as of the end of Q4-

2021; Vietnam as of Q1-2021; Ireland as of Q2-2020.

19

policy relative to 2020. The economic outlook for this year is subject to large downside

risks, primarily due to a large surge in COVID-19 cases starting in March 2022 that has led

to an acceleration in lockdowns of major cities.

China’s current account

surplus was stable,

increasing slightly to 1.8% of

GDP in 2021 from 1.7% of

GDP in 2020, in part

reflecting continued strong

global demand for

manufactured goods, buoyed

by China’s ability to expand

and maintain manufacturing

capacity despite pandemic-

related supply chain

disruptions. As such, goods exports increased by 28% last year. Goods imports grew by an

even more rapid 33% last year, in part reflecting higher commodity prices. China’s services

trade deficit remained subdued at 0.6% of GDP last year (compared to 1.0% of GDP in

2020) largely due to continued restrictions on outbound travel. Treasury assesses that in

2021, China’s external position was broadly in line with economic fundamentals and

desirable policies, with an estimated current account gap of 0.3% of GDP.

9

China’s bilateral goods trade surplus with the United States remains the largest by far of

any U.S. trading partner, growing to $355 billion in 2021 from $310 billion in 2020. While

export growth to the United States was broad based, electrical machinery and other

manufactured goods saw the largest increases last year. China ran a bilateral services trade

deficit with the United States of $15 billion last year. Overall, China’s bilateral goods and

services surplus with the United States reached $340 billion in 2021, compared with $285

billion in 2020.

China’s financial account swung into a surplus of $38 billion in 2021 from a deficit of $61

billion in 2020, amplifying appreciation pressures on the RMB. Net FDI inflows

strengthened to $206 billion from $99 billion in the prior year. Net portfolio inflows

moderated to $51 billion in 2021 from $96 billion in 2020 but showed an accelerating

trend over the course of the year as residents’ purchases of foreign securities moderated

while non-residents’ purchases of Chinese securities remained fairly strong. These capital

inflows were partially offset by a net other investment deficit of $230 billion, primarily

driven by large outflows of “currency and deposits” and loans.

10

A net errors and

omissions deficit of $167 billion provided another balancing outflow and suggests strong

undocumented capital outflows not captured in identified components of the financial

account, in line with previous years.

9

The estimated current account gap reflects offsetting factors, where pandemic related factors—specifically

adjustments for temporarily high levels of tourism, transportation, and medical goods flows—counteracted

the effect of macroeconomic policy distortions on China’s current account.

10

Excluding China’s SDR allocation, the “other investment” deficit was $271 billion.

-5

0

5

10

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Percent of GDP

China: Current Account Balance

Income Services Goods Current Account Balance

Sources: SAFE, Haver

20

The RMB appreciated by

2.7% against the dollar and

7.9% against the People’s

Bank of China’s (PBOC) China

Foreign Exchange Trade

System (CFETS) nominal

basket in 2021.

11

The real

effective exchange rate

strengthened by 4.4% last

year. The RMB experienced

its sharpest appreciation

against the dollar in the

second and fourth quarters of 2021 and saw its largest gains on a nominal effective basis

during periods in which the broad dollar was also strengthening, particularly the first and

fourth quarters of 2021. The RMB’s appreciation trend persisted in early 2022 but

reversed sharply in mid-April, when the RMB depreciated by 5.4% against the dollar in just

three weeks amid portfolio capital outflows, a darkening growth outlook, and a growing

divergence in expectations for monetary policy between China and the United States.

In 2021, the authorities implemented several regulatory measures that had the aggregate

effect of counteracting RMB appreciation pressures. In late May 2021, following two

months of nearly continuous appreciation of the RMB against the dollar, the PBOC

announced that it would raise the foreign currency required reserve ratio from 5% to 7%

for the first time since 2007, tightening onshore FX liquidity conditions. In December 2021,

as the RMB neared a three-year high against the dollar, the PBOC again raised this ratio by

two percentage points, and Chinese state media explicitly described this adjustment as a

tool to “deal with the appreciation of Chinese currency.” In 2021, the State Administration

of Foreign Exchange increased outbound investment quotas under the qualified domestic

institutional investment (QDII) program seven times, following three increases in 2020.

The quota increases over 2020-2021 opened headroom for an additional $54 billion in

capital outflows, more than the cumulative quota increases over the 11 years prior. In

September 2021, the PBOC launched the Southbound Bond Connect scheme, which permits

mainland investors to purchase up to $75 billion in Hong Kong-traded bonds annually.

China provides very limited transparency regarding key features of its exchange rate

mechanism, including the policy objectives of its exchange rate management regime, the

relationship between the PBOC and foreign exchange activities of the state-owned banks,

and its activities in the offshore RMB market. The PBOC manages the RMB through a range

of tools including setting the central parity rate (the “daily fix”) that serves as the midpoint

of the trading band against which the onshore RMB is allowed to trade within 2% in either

direction. Chinese authorities can directly intervene in foreign exchange markets as well as

influence the interest rates of RMB-denominated assets that trade offshore, the timing and

11

The CFETS RMB index is a trade-weighted basket of 24 currencies published by the PBOC.

85

90

95

100

105

110

85

90

95

100

105

110

Jan-15

Jan-16

Jan-17

Jan-18

Jan-19

Jan-20

Jan-21

Jan-22

Indexed December 2014 = 100

China: Exchange Rates

Bilateral vs. USD CFETS REER (monthly)

Sources: CFETS, FRB, BIS

21

volume of forward swap sales and purchases by China’s state-owned banks, and the

conversion of foreign exchange proceeds by state-owned enterprises.

The authorities have also used verbal intervention and their control over the daily fix to

influence the exchange rate. In May and November 2021, amid strong appreciation

pressure, PBOC statements sought to guide market expectations, emphasizing the need for

two-way movements in the exchange rate.

12

In January 2022, amid continued appreciation

pressure, PBOC Deputy Governor Liu Guoqiang forecast that both “market and policy

factors” will correct deviations in the exchange rate from the equilibrium level.

13

Meanwhile, over the course of last year both the frequency and magnitude of deviations

between the “daily fix” and market expectations increased, sending a signal to market

participants. China’s lack of transparency and use of a wide array of tools complicate

Treasury’s ability to assess the degree to which official actions are designed to impact the

exchange rate. Treasury will continue to closely monitor China’s use of exchange rate

management, capital flow, and regulatory measures and their potential impact on the

exchange rate.

China is an outlier among the economies covered in this Report in not disclosing its foreign

exchange market intervention, which forces Treasury staff to estimate China’s direct

intervention in the foreign exchange market.

China’s headline foreign

exchange reserves increased

by $34 billion over the course

of 2021, ending the year at

$3.3 trillion. Last year, the

PBOC’s foreign exchange

assets booked at historical

cost also increased on an

annual basis for the first time

since 2014, growing by $24

billion. Meanwhile, net

foreign exchange settlement

data, another proxy measure for foreign exchange intervention that includes the activities

of China’s state-owned banks, indicates net foreign exchange purchases of nearly $290

billion (1.6% of GDP) in 2021, adjusted for changes in outstanding forwards. The precise

causes for the large divergence between monthly changes in the PBOC’s foreign exchange

assets and net foreign exchange settlement data remain unclear.

14

As noted in previous

12

PBOC, “Deputy Governor Liu Guoqiang Answers Press Questions on RMB Exchange Rate,” May 23, 2021,

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688172/4157443/4253138/index.html ; PBOC, “The Eighth Working

Meeting of the National Foreign Exchange Market Self-Discipline Mechanism was Held,” November 18, 2021,

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/goutongjiaoliu/113456/113469/4392338/index.html.

13

PBOC, “Transcript of the Press Conference on Financial Statistics in 2021,” January 18, 2022,

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/goutongjiaoliu/113456/113469/4451702/index.html.

14

Historically, monthly changes in the PBOC’s foreign exchange assets and net FX settlement data have

provided roughly similar estimates of the direction and size of Chinese foreign exchange intervention. The

-200

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

Jan-15

Apr-15

Jul-15

Oct-15

Jan-16

Apr-16

Jul-16

Oct-16

Jan-17

Apr-17

Jul-17

Oct-17

Jan-18

Apr-18

Jul-18

Oct-18

Jan-19

Apr-19

Jul-19

Oct-19

Jan-20

Apr-20

Jul-20

Oct-20

Jan-21

Apr-21

Jul-21

Oct-21

Billion U.S. Dollars

China: Estimated FX Intervention

PBOC FX Assets Bank Net FX Settlement

Sources: PBOC, SAFE, U.S. Treasury Estimates

22

Treasury FX Reports, the divergence between these proxy measures could be an indication

that monthly changes in the PBOC’s foreign exchange assets are not adequately capturing

the full range of China’s intervention methods, including official intervention conducted

through the state-owned banks. Overall, these developments highlight the need for China

to improve transparency regarding its foreign exchange intervention activities.

In formulating near-term macroeconomic policy, the authorities will need to balance

support for economic growth against long-term reform needs and continued risks to

financial stability. Near-term support for the property sector to prevent broader contagion

should be accompanied by measures to improve resolution and insolvency frameworks in a

timely manner. In that respect, the authorities’ introduction of a draft Financial Stability

Law is a welcome development. On the fiscal front, the central government retains space

for more accommodation; channeling this stimulus through its own budget would also

mitigate stresses on local government balance sheets. Directing additional support to

Chinese households would help to support private consumption amid ongoing pandemic-

related uncertainty. The authorities should refrain from exacerbating economic

imbalances through policies that stimulate exports and investment-led growth. Instead,

the authorities should prioritize measures to support household consumption, expand the

social safety net, and renew efforts to reduce the role of state-owned enterprises and state

intervention in the economy.

Japan

Japan’s economy rebounded in 2021, growing 1.7% following the substantial 4.5%

contraction in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccinations reaching 80% of the

population and an easing of pandemic-related supply chain constraints supported the

recovery. Although growth was positive overall in 2021, growth contracted on a quarter-

by-quarter basis in both the first and third quarters owing to pandemic-related

retrenchments in spending and investment. GDP growth should advance incrementally in

2022, although a terms of trade shock in commodities and a potential slowdown among

regional trade partners pose downside risks. Though inflation has risen recently, monetary

policy remains highly accommodative on the expectation that inflation will not sustainably

breach the 2% target.

divergence between these indicators continued to widen in 2021, and the gap reached a six-year high on an

annual basis last year.

23

Japan’s current account

surplus was stable, remaining

at 2.9% of GDP in 2021 as in

2020. This is slightly below

the 3% surplus level the

current account has averaged

since 2000. The goods trade

surplus moderated to 0.3% of

GDP in 2021 amid rising

commodity prices. Likewise,

the services balance

remained in deficit, widening

slightly to 0.8% of GDP, due largely to pandemic-related retrenchment in the tourism

sector. Japan’s substantial net foreign income balance continues to drive the current

account surplus. At 3.3% of GDP, net income flows for 2021 are moderately greater than

the four quarters ending June 2021 when net inflows tallied 3.1% of GDP. Both primary

and secondary income components increased marginally compared to totals ending in the

second half of 2021, with primary income rising to 3.8% of GDP and secondary income

rising to -0.4% of GDP. Last year, primary income outflows were 2% of GDP, a modest level

for a country of Japan’s size and development, which reflects, in part, a low stock of FDI

within Japan.

15

Treasury assesses that in 2021, Japan’s external position was stronger than

warranted by economic fundamentals and desirable policies, with an estimated current

account gap of 2.0% of GDP.

16

The goods and services trade surplus with the United States

was $60 billion in 2021, up 8%, or $4.4 billion, compared to 2020.

Japan experienced net capital outflows of 1.9% of GDP in 2021, driven by sizeable direct

investment abroad (2.4% of GDP) and loan and trade credit outflows (1.9%) that were

partly offset by net portfolio inflows (4.5% of GDP) that occurred amidst a sustained

depreciation of the yen.

The yen depreciated 10.4%

against the U.S. dollar in

2021, largely on widening

interest rate differentials

between the United States

and Japan. Last year’s

depreciation is a marked

contrast with 2020 when the

yen strengthened 5.3%. Since

the beginning of the year, the

yen has continued to decline,

depreciating an additional

15

In 2021 Japan’s primary income outflows were the lowest among G7 economies, which averaged 4.2% of

GDP in 2021, more than twice that of Japan.

16

Treasury’s estimate of the current account gap assumes that Japan’s depressed tourism flows over the

course of the pandemic are largely transitory in nature and will dissipate over the medium term.

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Percent of GDP

Japan: Current Account Balance

Income Services Goods Current Account Balance

Sources: Bank of Japan, Ministry of Finance, Cabinet Office

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

Jan-07

Jan-08

Jan-09

Jan-10

Jan-11

Jan-12

Jan-13

Jan-14

Jan-15

Jan-16

Jan-17

Jan-18

Jan-19

Jan-20

Jan-21

Jan-22

Indexed to 20Y Avg = 100

Japan: Exchange Rates

Bilateral vs. USD NEER REER

Sources: FRB, Bank for International Settlements

24

11.3% as interest rate differentials with the United States continue to widen and Japanese

monetary authorities maintain yield curve control operations. On a real effective basis, the

yen depreciated 10.0 % last year and currently sits near 50-year lows.

Japan is transparent with respect to foreign exchange operations, regularly publishing its

foreign exchange interventions each month. It has not intervened in foreign exchange

markets since 2011. Treasury’s firm expectation is that in large, freely traded exchange

markets, intervention should be reserved only for very exceptional circumstances with

appropriate prior consultations.

Japanese policymakers have provided an appropriately sizable fiscal and monetary

response to support the economy amid the pandemic. Japan should remain responsive to

new developments that warrant additional support but renew its focus on implementing

structural reforms that would lift investment and improve potential growth. To achieve

this, policymakers could promote labor mobility to enhance the productivity of firms and

raise wage growth; support digitalization across industries, particularly small and medium

enterprises; further promote career development and advancement among female workers

who disproportionately suffer from underemployment; and advance enduring corporate

governance reforms.

Korea

Korea’s real GDP grew by 4% in 2021 after a modest 1% contraction in 2020. Robust

growth in 2021 was led by a strong recovery in private consumption and government

spending, both supported by fiscal and public health measures designed to contain, and

now adapt to, the COVID-19 pandemic. The Korean government maintained an expanded

2021 budget that kept the fiscal deficit at 4.4% of GDP, roughly consistent as the year

before. The government has kept fiscal policy accommodative in 2022 to support the

recovery, with an expected fiscal deficit of 3.3%. With a low debt-to-GDP ratio of

approximately 50%, Korea has ample fiscal space to continue to support economic growth

while paring down pandemic relief. Korea’s central bank began to steadily tighten

monetary policy from August 2021 to address financial imbalances and above-target

inflation, implementing its fourth quarter-point policy rate increase to 1.75% in May 2022.

Korea’s current account

surplus widened to 4.9% of

GDP in 2021 from 4.6% a

year prior. The increase was

driven by a narrowing in the

services deficit, which

continued to be affected by

pandemic induced distortions

in transportation and tourism

balances, and a structural

increase in the income

balance due to Korea’s

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Percent of GDP

Korea: Current Account Balance

Income Services Goods Current Account Balance

Sources: Bank of Korea, Haver

25

growing net foreign assets. Korea’s bilateral trade surplus with the United States, inclusive

of goods and services, increased to $22 billion in 2021, up from $17 billion over the same

period in the year prior. Treasury assesses that in 2021, Korea’s external position was

weaker than warranted by economic fundamentals and desirable policies, driven in part by

the effect of demographics on national saving.

The Korean won depreciated

steadily throughout 2021,

weakening 8.6% against the

dollar and 5.3% on a real

effective basis. The won has

continued to weaken since

the beginning of 2022,

depreciating a further 5.4%

against the dollar by end-

April. Moderation in Korea’s

goods trade balance driven

by rising commodity prices as

well as sizeable equity outflows stemming from rising global interest rates and elevated

geopolitical uncertainty have been factors in persistent won weakness. Korea’s national

pension fund’s total foreign asset holdings increased by around $60 billion in 2021, from

$270 billion to $330 billion, predominantly driven by valuation changes.

Korea reported net foreign

exchange sales of $14 billion

(0.8% of GDP) in the spot

market, which had the effect

of stemming won

depreciation in 2021.

Treasury estimates that the

Korean authorities made