The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Impact Evaluation of the Minnesota Reading Corps K-3 Program

M

arch 2014

Authors

This study was conducted by researchers from NORC at the University of Chicago and TIES:

Carrie E. Markovitz, Ph.D., Principal Research Scientist, NORC at the University of Chicago

Marc W. Hernandez, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist, NORC at the University of Chicago

Eric C. Hedberg, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist, NORC at the University of Chicago

Benjamin Silberglitt, Ph.D., Director of Software Applications, TIES

This report represents the work and perspectives of the authors and is the product of professional research. It does

not represent the position or opinions of CNCS, the federal government, or the reviewers.

Acknowledgements

Many individuals and organizations have contributed to the design and implementation of the Impact Evaluation of

the K-3 Minnesota Reading Corps Program. While it is not possible to name everyone, we would like to acknowledge

some of the individuals and organizations who have played a significant role in the completion of the study:

■ The site liaisons who managed the data collection at individual schools: Athena Diaconis, Marissa Kiss,

Heather Langerman, Arika Garg, and Molly Jones. We would like to extend a special thank you to Elc

Estrera and Athena Diaconis for assisting with the production of data tables.

■ The schools and their staff, as well as the AmeriCorps members serving in the schools, for agreeing to

participate in our study and for shouldering most of the responsibility for the collection of student

assessment data.

■ The CNCS Office of Research and Evaluation for providing guidance and support throughout the design and

implementation of the study.

■ The Program Coordinators, Master Coaches, Internal Coaches, AmeriCorps members, and staff of the

Minnesota Reading Corps, and especially Audrey Suker and Sadie O’Connor of ServeMinnesota, for their

strong support and assistance.

Citation

Markovitz, C.; Hernandez, M.; Hedberg, E.; Silberglitt, B. (2014). Impact Evaluation of the Minnesota Reading Corps

K

-3 Program. NORC at the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL.

This report is in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it in whole or in part is granted. Upon request, this

material will be made available in alternative formats for people with disabilities.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page i

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... v

Key Study Findings .............................................................................................................................................. v

About the Minnesota Reading Corps .................................................................................................................. vi

Impact Evaluation Methodology ......................................................................................................................... viii

Findings and Conclusions ................................................................................................................................... xi

Final Thoughts ................................................................................................................................................... xv

I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1

II. About Minnesota Reading Corps ..................................................................................................................... 4

A. Statewide Implementation of MRC: 2003-2013 ........................................................................................ 4

B. Foundational Framework and Staffing Structure in MRC ......................................................................... 5

C. Summer Institute Training......................................................................................................................... 9

D. The Role of Data in MRC Program Implementation and Improvement................................................... 10

III. Impact Evaluation of the Minnesota Reading Corps K-3 Program ............................................................. 13

A. Evaluation Logic Model........................................................................................................................... 13

B. K-3 Impact Evaluation Research Questions ........................................................................................... 15

C. School Selection ..................................................................................................................................... 16

D. Random Assignment of Students Within Schools................................................................................... 18

E. Use of Administrative Data ..................................................................................................................... 22

F. Analysis .................................................................................................................................................. 25

G. Limitations of the Study .......................................................................................................................... 28

IV. Fall-Winter Experimental Study Findings ...................................................................................................... 33

Overall Impact Findings ..................................................................................................................................... 34

Findings by Major Demographic Groups ............................................................................................................ 38

AmeriCorps Member and School Level Effects.................................................................................................. 46

V. Full Year Non-Experimental Study Findings ................................................................................................. 48

Week Over Week and Cumulative Effects of MRC Program ............................................................................. 49

VI. Exploratory Analysis ....................................................................................................................................... 56

Analys

is of Probabilities of Group Membership.................................................................................................. 57

Analysis Using Spline Models ............................................................................................................................ 58

VII. Conclusions ..................................................................................................................................................... 60

Program Implications from Conclusions ............................................................................................................. 66

Recommendations for Future Research ............................................................................................................ 68

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page ii

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

List of Figures

Figure 1. Response to Intervention Tiers ........................................................................................................ vii

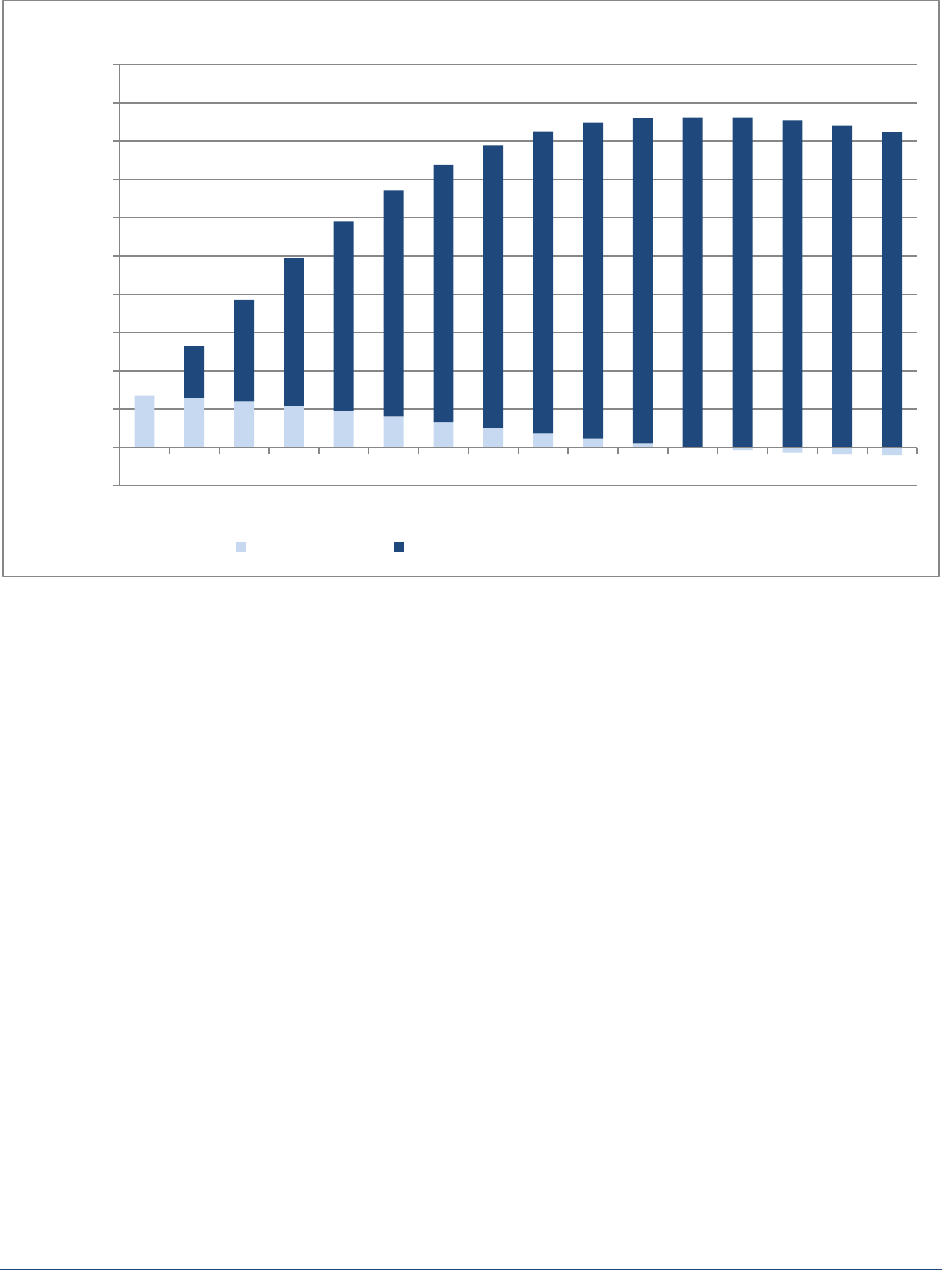

Figure 2. Mean scores for Kindergarten program and control students ........................................................... xi

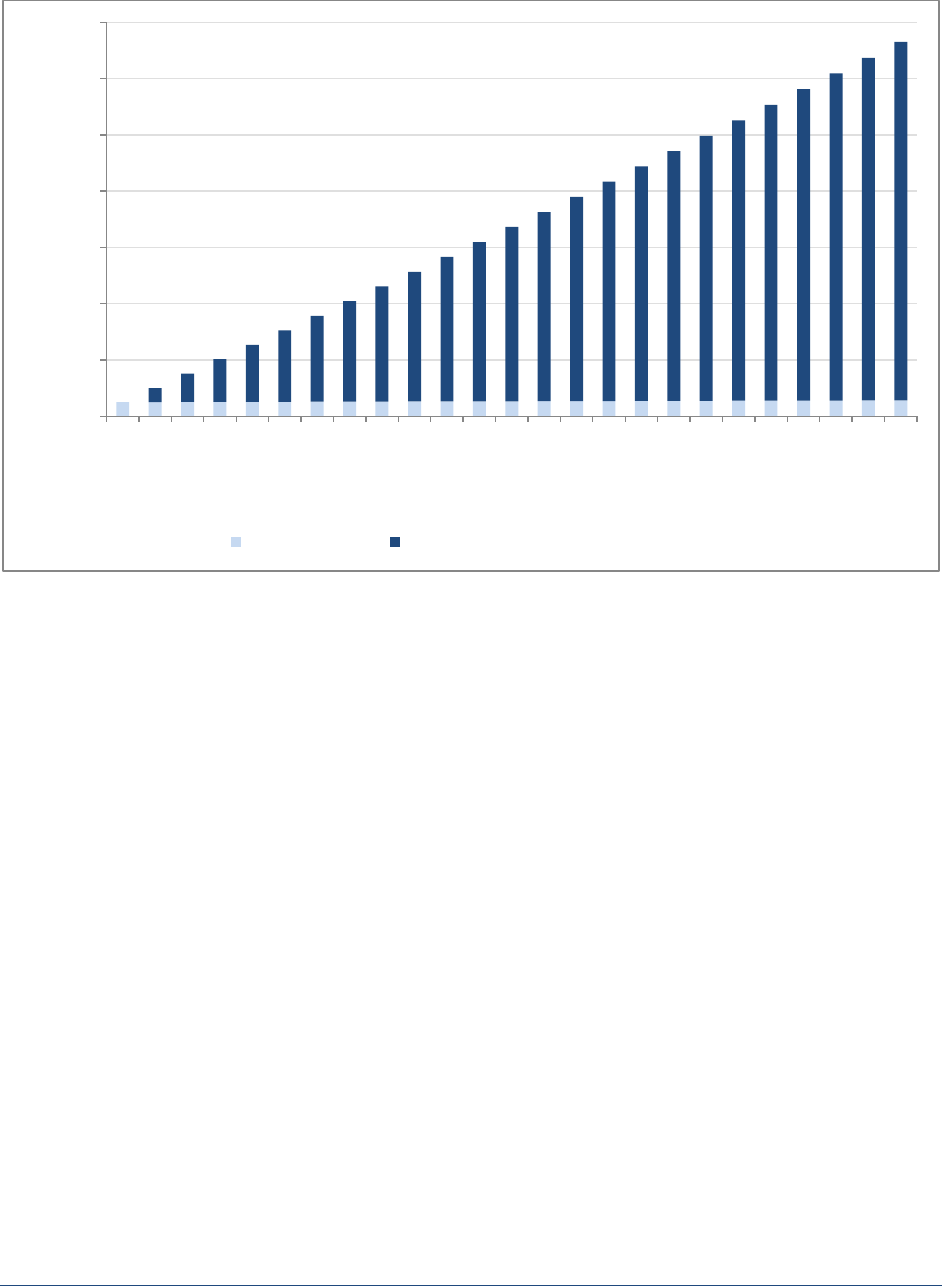

Figure 3. Cumulative week over week growth in third grade words read aloud for students receiving MRC

tutoring ........................................................................................................................................... xiv

Figure II.1. Response to Intervention Tiers .......................................................................................................... 6

Figure II.2. MRC Supervisory Structure ............................................................................................................... 8

Figure IV.1. Mean scores on Kindergarten program and control students .......................................................... 35

Figure IV.2. Mean scores on first grade program and control students .............................................................. 36

Figure IV.3. Mean scores on second grade program and control students ......................................................... 37

Figure IV.4. Mean scores on third grade program and control students ............................................................. 38

Figure V.1. Cumulative week over week growth in Kindergarten letter sounds for students

receiving MRC tutoring .................................................................................................................... 51

Figure V.2. Cumulative week over week growth in first grade nonsense word letter sounds for students

receiving MRC tutoring in the Fall ................................................................................................... 52

Figure V.3. Cumulative week over week growth in first grade words read aloud for students

receiving MRC tutoring in Spring ..................................................................................................... 53

Figure V.4. Cumulative week over week growth in second grade words read aloud for students receiving MRC

tutoring ............................................................................................................................................ 54

Figure V.5. Cumulative week over week growth in third grade words read aloud for students receiving MRC

tutoring ............................................................................................................................................ 55

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page iii

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

List of Tables

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of students in the MRC K-3 Impact Evaluation

(Fall 2012) ........................................................................................................................................ ix

Table II.1. MRC K-3 CBM assessments and benchmarks by grade and season ............................................. 11

Table III.1. Characteristics of schools participating in the MRC K-3 Impact Evaluation

(Fall 2012) ....................................................................................................................................... 17

Table III.2. Student participants for the MRC K-3 Impact Evaluation (Fall 2012) .............................................. 20

Table III.3. Student participants’ DLL Status by race/ethnicity for the MRC K-3 Impact

Evaluation (Fall 2012) ...................................................................................................................... 20

Table III.4. Differences between control and program group students by grade (Fall 2012) ............................. 21

Table III.5. Alternative interventions received by control group students by school (2012-13

school year) ..................................................................................................................................... 24

Table IV.1. Mean scores for all program and control students at week 16 by grade ......................................... 34

Table IV.2. Chi-Square Test Results for Subgroup Variable Moderator Effects ................................................ 39

Table IV.3. Mean scores for program and control students at week 16 by grade and gender ........................... 40

Table IV.4. Mean scores for program and control students at week 16 by grade and select racial groups ....... 41

Table IV.5. Mean scores for program and control students at week 16 by grade and White and

non-White racial group .................................................................................................................... 42

Table IV.6. Mean scores for program and control students at week 16 by grade and Dual

Language Learner status ................................................................................................................. 43

Table IV.7. Mean scores for program and control students at week 16 by grade and Free and

Reduced Price Lunch eligibility ........................................................................................................ 44

Table IV.8. Mean scores for program and control students at week 16 by grade and proximity

to Fall benchmark (baseline) .......................................................................................................... 45

Table IV.9. AmeriCorps member- and school-level interclass correlations and standard

errors based on student-level program effects (Winter-Fall benchmark) by grade .......................... 46

Table IV.10. Effects of AmeriCorps member characteristics on program students' weekly

assessment scores .......................................................................................................................... 47

Table V.1. Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of number of weeks of tutoring by program

assignment and semester ............................................................................................................... 49

Table VI.1. Estimated probabilities of effect patterns for students receiving 10 weeks of MRC tutoring by initial

study group assignment (program or control group) ........................................................................ 57

Table VI.2. Parameter estimates of linear growth (slope) and adjustments across baseline,

program and post-program phases. ................................................................................................ 59

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page iv

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Executive Summary

Minnesota Reading Corps (MRC) is the largest AmeriCorps State program in the country. The goal of MRC is to

ensure that students become successful readers and meet reading proficiency targets by the end of the third grade.

To meet this goal, the MRC program, and its host organization, ServeMinnesota Action Network, recruit, train, place

and monitor AmeriCorps members to implement research-based literacy enrichment activities and interventions for

at-risk Kindergarten through third grade (K-3) students and preschool children.

Starting in 2011, the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) sponsored a randomized controlled

trial (RCT) impact evaluation of over 1,300 K-3 students at 23 participating schools who were determined to be

eligible for the MRC program during the 2012-2013 school year. The goal of the impact evaluation was to determine

both the short- and long-term impacts of the MRC program on elementary students’ literacy outcomes.

Key Study Findings

Kindergarten, first, and third grade students who received MRC tutoring achieved significantly higher

literacy assessment scores than students who did not.

The magnitude of MRC tutoring effects differed by grade, with the largest effects found among the youngest students

(i.e., Kindergarten and first grade students), and the smallest effects among the oldest students (i.e., third grade

students). Significant effects were not found for second grade students. In later grades (second and third), when

students begin the more complex task of reading connected text, the MRC program appears to take longer than a

single semester to produce significant improvements in student literacy. However, additional non-experimental

analyses suggest that, over a longer period of time, the MRC program changes second and third grade students’

growth trajectories towards increasing their reading proficiency.

MRC tutoring resulted in statistically significant impacts across multiple racial groups. In Kindergarten and

first grade tutoring was effective despite important risk factors, including Dual Language Learner status and

Free and Reduced Price Lunch eligibility.

A statistically significant impact of MRC tutoring was detected among Kindergarten and first grade students despite

gender, minority group status, Dual Language Learner (DLL) status, and Free or Reduced Price Lunch (FRPL)

eligibility. For each of these characteristics, students who received MRC tutoring significantly outperformed control

students who did not receive tutoring on grade-specific literacy assessments. Third grade White, native English

speaking (i.e., non-DLL), and eligible for FRPL students on average produced positive significant differences

between program and control group students, while a statistically significant finding was not found for third grade

Black and Asian students and third grade DLL students.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page v

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

The MRC program is replicable in multiple school settings using AmeriCorps members with varied

backgrounds.

Student assessment scores did not vary by AmeriCorps member characteristics (i.e., gender, race, age, years of

education, full/part time status, or prior education experience) nor by the specific school at which the tutoring

occurred. These results support the conclusion that the MRC program is replicable in multiple school settings using

AmeriCorps members with diverse backgrounds. Many MRC AmeriCorps members have no previous experience

working in schools, with students, or in the domain of literacy. The lack of member-level and school-level effects on

student outcomes validates MRC’s approach to training, coaching and supervision, as well as their intentional

recruitment of members with diverse backgrounds who do not necessarily have formal training or experience in

education or literacy instruction.

About the Minnesota Reading Corps

The MRC program was started in 2003 to provide emergent literacy enrichment and tutoring to children in four

preschool (PreK) Head Start programs. In 2005, MRC expanded its program to serve students in Kindergarten

through third grade (K-3). The core activities of MRC, and its host organization, ServeMinnesota Action Network, are

to recruit, train, place and monitor AmeriCorps members to implement research-based literacy interventions for at-

risk K-3 students and preschool children.

AmeriCorps members in the MRC program serve in school-based settings to implement MRC literacy strategies and

conduct interventions with students using a Response to Intervention (RtI) framework. The key aspects of the MRC

RtI framework are:

■ Clear literacy targets at each age level from PreK through grade 3

■ Benchmark assessment three times a year to identify students eligible for one-on-one interventions

■ Scientifically based interventions

■ Frequent progress monitoring during intervention delivery

■ High-quality training and coaching in program components, and literacy assessment and instruction

In the RtI framework, data play the key roles of screening students’ eligibility for services and then monitoring

students’ progress towards achieving academic goals (i.e., benchmarks). The Minnesota Reading Corps screens

students for program eligibility three times a year (i.e., Fall, Winter, Spring) with two sets of grade-specific, literacy-

focused general outcome measures (i.e., IGDI for PreK and AIMSweb for K-3) that possess criterion-referenced

grade- and content-specific performance benchmarks. Program staff use scores from these general outcome

measures to categorize students into one of three possible tiers (i.e., proficiency levels): Tier 1 students score at or

above benchmark and benefit from typical classroom instruction (75-80% of students score in this category); Tier 2

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page vi

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

students score below benchmark and require specific supplemental interventions until they meet benchmarks (15-

20% of students fall into this category); and Tier 3 students require intensive intervention provided by a special

education teacher or literacy specialist and often have individualized educational plans (5-10% of students qualify for

this category).

Figure 1. Minnesota Reading Corps Response to Intervention Tiers

The MRC K-3 program provides one-on-one tutoring where members provide supplemental individualized literacy

interventions to primarily Tier 2 students in Kindergarten through third grade. Members in the MRC PreK program

provide whole-class literacy enrichment for all students (i.e., Tier 1) and a targeted one-on-one component, where

members provide individualized interventions to students struggling with emergent literacy skills (i.e., Tiers 2 and 3).

At the K-3 level, which is the focus of this study, the program is focused on the “Big Five Ideas in Literacy” as

identified by the National Reading Panel, including phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and

comprehension. AmeriCorps members serve as one-on-one tutors for Tier 2 students. Full-time members individually

tutor approximately 15-18 K-3 students daily for 20 minutes each. The MRC tutoring interventions supplement the

core reading instruction provided at each school. The goal of the tutoring is to raise individual students’ literacy levels

so that they are on track to meet or exceed the next program-specified literacy benchmark. One variation among K-3

members is the Kindergarten-Focus (K-Focus) position. K-Focus members continue to tutor first to third grade

students, though they tend to spend a majority of their time providing Kindergarteners with two small-group (20-

minute) sessions daily, for a total of 40 minutes of literacy-focused intervention.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page vii

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Impact Evaluation Methodology

The K-3 impact evaluation is one of several complementary studies being completed on the MRC program: a process

assessment of the MRC program in 20 PreK and K-3 sites (completed in Spring 2013);

0F

1

a quasi-experimental impact

evaluation of the MRC PreK program on preschool students’ emergent literacy outcomes (forthcoming in Fall 2014);

and a survey of AmeriCorps members (completed in Fall 2013). The impact evaluation focused on the following

research questions:

1. What is the impact of the MRC program on student literacy outcomes?

a. Does the impact vary by student characteristics/demographics?

b. Do assessment scores vary by AmeriCorps member characteristics/demographics?

2. Does the impact of the program vary week to week? Does the number of weeks of intervention (i.e., dosage)

impact student literacy outcomes?

3. Does participation in MRC have a longer-term impact on student literacy outcomes as measured at the end of

the school year?

The methodology used was informed by the 2008-2009 and 2010-2011 annual Minnesota Reading Corps

evaluations.

1F

2

School and Student Selection

A diverse and representative sample of 25 schools that had fully implemented the MRC K-3 program for at least two

consecutive years were selected for the study. Due to the voluntary nature of the study, it was not possible to employ

simple random sampling for the selection of schools; however, stratified random sampling was employed to select

schools and school-level weights were used in our statistical models. Approximately 200 eligible schools were

stratified by urbanicity (i.e., urban, suburban, and rural) using the MRC program regions and then selected using

Probability Proportional to Size (PPS), whereby larger schools with a more pronounced need (defined as the number

of students previously served by MRC) had a higher probability of selection. Using PPS ensured a statistically

adequate sample size to conduct the K-3 impact evaluation. Participation in the evaluation was voluntary;

1

Hafford, C., Markovitz, C., Hernandez, M, et al. (February 2013). Process Assessment of the Minnesota Reading Corps Program. (Prepared

under contract to the Corporation for National and Community Service). Chicago, IL: NORC at the University of Chicago.

2

Bollman, K. & Silberglitt, B. (2009). Minnesota Reading Corps Final Evaluation 2008-2009. Minneapolis, MN: MRC.; Bollman, K. & Silberglitt,

B. (2011). Minnesota Reading Corps Final Evaluation 2010-2011. Minneapolis, MN: MRC.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page viii

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

consequently, 23 elementary schools agreed to participate in the K-3 impact evaluation during the 2012-2013 school

year.

2F

3

All students at the 23 sampled schools identified by Fall benchmark scores as eligible for MRC services (i.e., Tier 2)

were randomly assigned to either the MRC program (i.e., treatment) or control group at the beginning of the first

semester prior to the start of tutoring. Each eligible student in each grade within a school was matched with another

eligible student based upon their Fall benchmark score. Students within pairs were then randomly assigned to either

the program or control condition. This matched pair design ensured that students in the program and control groups

had similar Fall benchmark scores at the start of the school year. In the end, a total of 1,530 eligible students were

selected to participate in the evaluation. During the school year, some students left the school area (i.e., moved) or

were chronically absent and did not receive regular MRC tutoring or assessments. These students and their matched

pair were removed from the analytic sample (i.e., pairwise deletion). Thus, the final sample of students included in

the evaluation totaled 1,341 students.

3F

4

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of students in the MRC K-3 Impact Evaluation (Fall 2012)

Kindergarten

(N=359)

1

st

Grade

(N=409)

2

nd

Grade

(N=265)

3

rd

Grade

(N=308)

Mean Mean Mean Mean

Female

56%

52%

46%

46%

Race/Ethnicity

White

30%

39%

36%

40%

Black 33 22 29 23

Asian 27 26 25 27

Hispanic

7

12

9

8

Other

3

1

1

2

Dual Language Learner (DLL) 26% 37% 37% 31%

Free and Reduced Price Lunch (FRPL)

76

72

75

71

Data Collection

In the Fall, Winter, and Spring of each school year, AmeriCorps members collect general outcome measure data

using the AIMSweb literacy assessments. The AIMSweb assessments evaluate three critical literacy skills that

research on literacy development has confirmed are appropriate for specific grade levels and seasons: 1) letter

sound fluency (Kindergarten), 2) nonsense word fluency (first grade –Fall/Winter), and 3) oral reading fluency (first

grade –Winter/Spring, second and third grades). These assessments are collectively called curriculum-based

3

Schools who did not participate referenced scheduling conflicts and staffing shortages as possible reasons.

4

For each grade, we demonstrate low levels of attrition assuming the “liberal” standard outlined in the WWC Evidence Review Protocol for

Early Childhood interventions (Version 2):

http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/reference_resources/ece_protocol_v2.0.pdf

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page ix

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

measures (CBM), because they correspond closely with curricular expectations for literacy skills at each

developmental level. These data are used in the Fall benchmark data collection period to identify students who are in

need of MRC support. Tier 2 students receive MRC intervention services until their progress monitoring data shows

that they have achieved 3 to 5 consecutive data points above projected growth trajectory (i.e., the aimline) and two

scores at or above the upcoming season benchmark target (Winter or Spring).

AmeriCorps members were asked to collect both benchmark and weekly progress monitoring data from students in

both the program and control groups comprising the primary data for the evaluation. Because the evaluation was

designed to measure the impact of MRC program participation relative to nonparticipation, students in the control

group were embargoed from receiving tutoring services during the first semester of the school year. It was not

possible to continue the experimental RCT throughout the entire school year due to school apprehension about

withholding MRC services. As such, all program and control students who were eligible at the Winter benchmark to

participate in the MRC program were allowed to receive services during the second semester of the 2012-2013

school year (Winter 2013 – Spring 2013). However, benchmark and weekly progress monitoring data continued to be

collected by AmeriCorps members on all students in the study throughout the entire school year.

Analysis

Three specific and separate analysis approaches were used to address the three major research questions of the

study:

1. To address the impact of the MRC program on student literacy outcomes (RQ1), a Fall-Winter Experimental

Study analyzed 16 weeks of assessment data collected on the program and control groups during which the

control group was embargoed from participation in the MRC program (i.e., first semester of the 2012-2013

school year from the September 2012 Fall benchmark through the January 2013 Winter benchmark). We

also conducted analyses to examine whether differential effects of the program existed for specific

subgroups of students based on the following student characteristics: gender (male/female), race (White,

Black, Asian; White/non-White), Dual Language Learner (DLL) status (yes/no), and Free or Reduced Price

Lunch eligibility (yes/no).

2. To understand how the pattern of program impacts vary week to week (RQ2), a Full Year Non-Experimental

Study analyzed the full year of assessment data collected on the program and control groups during both

semesters of the 2012-2013 school year. This non-experimental analysis included weekly assessment

scores from the second semester, during which all students in the control group became eligible for MRC

tutoring services.

3. To estimate whether participation in MRC has a longer-term impact on student literacy outcomes (RQ3), an

Exploratory Analysis of the full year of assessment data focused on the longer-term effects of the program

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page x

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

on students’ proficiency levels by examining all students who received MRC services at any point

throughout the school year, despite initial assignment to program or control groups.

Findings and Conclusions

Below, the evaluation team offers our conclusions based on the study findings and organizes them by the three major

research questions, followed by final thoughts on the implications of these findings for the future of the MRC

program.

Research Question #1: What is the impact of the MRC program on student literacy outcomes?

The results of the Fall-Winter Experimental Study showed that Kindergarten, first and third grade students who

received MRC tutoring achieved significantly higher literacy assessment scores by the end of the first semester than

did control students who did not participate in MRC tutoring. The magnitude of MRC tutoring effects differed by

grade, with the largest effects found among the youngest students (i.e., Kindergarten and first grade students), and

the smallest effects among the oldest students (i.e., third grade students). Significant effects were not found for

second grade students.

Figure 2. Mean scores for Kindergarten program and control students

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

1 4 7 10 13 16

Number of Letter Sounds

Week

Program

Control

Fall Benchmark

Winter Benchmark

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page xi

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Kindergarten students who participated in the MRC program produced more than twice as many correct letter sounds

by the end of the first semester than did students in the control condition. Similarly, first grade students participating

in MRC tutoring demonstrated significantly higher letter sounds embedded within nonsense words than students in

the control group. In contrast to the findings for Kindergarten and first grade students, the effect of the MRC program

on oral reading fluency was significant but small for third grade students and not statistically significant for second

grade students.

There are several possible explanations for the difference in program effects found in younger and older students.

Younger students are more likely to qualify to receive MRC interventions due to a general lack of school readiness

and insufficient exposure to academic language, books, and print. As students progress from Kindergarten into later

grades, students are more likely to be eligible for MRC services because they are struggling to acquire or integrate

needed skills, requiring significantly more in-depth intervention and time to remedy. When we consider that oral

reading is a more challenging skill to acquire and that older children who are eligible for MRC services also are more

likely to have experienced challenges mastering prerequisite skills, it is not surprising that it may take longer than a

single semester for second and third grade students to accumulate substantial effects of the MRC program. Whereas

lack of exposure in young children can be relatively quickly remedied by intensive and explicit instruction, learning

challenges in older children can take longer to overcome.

1a. Does the impact vary by student characteristics/demographics?

A statistically significant impact of MRC tutoring was detected among Kindergarten and first grade students despite

gender, minority status, DLL status, or FRPL eligibility. For each of these characteristics, students who received MRC

tutoring significantly outperformed control students who did not receive tutoring on grade-specific literacy

assessments. Among third grade students, an impact was not detected within all subgroups. Third grade White,

native English speaking (i.e., non-DLL), and FRPL eligible students all produced significant differences between

program and control group students. In contrast, among third grade Black and Asian students and third grade DLL

students a statistically significant finding was not found between students who received MRC tutoring and control

group students who did not participate in the program.

1b. Do assessment scores vary by AmeriCorps member characteristics/demographics?

Assessment scores did not vary by AmeriCorps member characteristics (i.e., gender, race, age, education, full/part

time status, or years of education) nor by the specific school at which the tutoring occurred. These results support the

conclusion that the MRC program is replicable in a variety of school settings using AmeriCorps members with diverse

backgrounds. Many MRC members have no previous experience working in schools, with students, or in the domain

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page xii

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

of literacy. In the Process Assessment of the Minnesota Reading Corps,4F

5

we concluded that the MRC program’s

high-quality training regime, research-based scripted interventions, regular objective assessment, ongoing on-site

coaching, and multi-layered supervisory structure resulted in high levels of fidelity of program implementation and

positive impacts on student literacy outcomes. The results of the Fall-Winter Experimental Study showed

quantitatively that these critical program supports indeed reduced variability in the interventions delivered by

AmeriCorps members within diverse school settings, such that the impact of member characteristics and individual

school effects on K-3 students was minimized.

Research Question #2: Does the impact of the program vary week to week?

While the Fall-Winter Experimental Study examined the overall impact of the program during the first semester, the

Full Year Non-Experimental Study examined estimates of week over week impacts to identify patterns in student

growth by grade. After the Fall semester, all students in the control group became eligible for MRC tutoring services,

were reassessed, and, if found eligible, could begin receiving MRC services in the second semester. Although the

experimental portion of the evaluation ended after the Winter benchmark (i.e., first semester), weekly assessment

data continued to be collected for the remainder of the school year from all students initially assigned in the Fall to

the program and control groups. The full-year data was then used to estimate week over week growth in literacy

outcomes for the average student who received tutoring during the 2012-2013 school year.

The analysis demonstrates that patterns in week over week gains among students receiving MRC tutoring vary by

grade. Kindergarten students showed immediate and large gains, the largest of which occurred in the first few weeks

of tutoring. In contrast, first, second and third grade students showed small, but steady week over week gains

throughout the entire period of analysis. An important consideration when interpreting these findings is that roughly

half of the schools in our study sample had K-Focus AmeriCorps members. While the typical MRC K-3 program

provides students with one 20-minute session per day, in the K-Focus program, each Kindergarten student

participates in two (20-minute) sessions daily, for a total of 40 minutes of literacy-focused instruction. Therefore, it is

reasonable to consider that the more intensive, higher dosage intervention for Kindergarten students in some schools

may have contributed to producing the large and early effects we observed in the week over week findings.

In contrast to the findings for Kindergarten students, the pattern of gains among first, second and third grade students

continued to build throughout the study period. These findings are not unexpected, given older program eligible

students are likely to need more intensive literacy intervention and practice, while younger students can benefit from

increased exposure to literacy activities and time on task.

5

Hafford, C., Markovitz, C., Hernandez, M, et al. (February 2013). Process Assessment of the Minnesota Reading Corps Program. (Prepared

under contract to the Corporation for National and Community Service). Chicago, IL: NORC at the University of Chicago.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page xiii

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

The findings for both second and third grade students indicate that the effects found in the Fall-Winter Experimental

Study may have been more substantial if it had been possible to follow students for a longer period of time beyond 16

weeks. Thus, if the timeline for the experimental study could have been lengthened to allow observation of

differences in scores between the program and control group of students over an entire school year, our finding for

second and third grade students may have been more substantial.

Figure 3. Cumulative week over week growth in third grade words read aloud for students receiving MRC

tutoring

Research Question #3: Does participation in MRC have a longer-term impa

ct on student literacy outcomes as

measured at the end of the school year?

In the Exploratory Analysis, the evaluation team found evidence that participation in the MRC program results in

longer-term effects on literacy outcomes when interventions begin earlier in the school year. When MRC

interventions are implemented later in the school year (i.e., second semester), the probability of progressing and

staying above benchmark decreases, while the likelihood of remaining chronically behind increases substantially.

The findings showed that program group students who received tutoring assistance early in the school year have

more than twice the likelihood of remaining above benchmark for the remainder of the school year compared to

students assigned to the control group who received equal amounts of tutoring assistance, but later in the school

year. The higher likelihood for program group students indicates that early intervention by the MRC program,

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

0-1

1-2

2-3

3-4

4-5

5-6

6-7

7-8

8-9

9-10

10-11

11-12

12-13

13-14

14-15

15-16

16-17

17-18

18-19

19-20

20-21

21-22

22-23

23-34

24-25

Weekly growth in Number

of Words Read Aloud

Week of sessions

Weekly growth Sum of weekly growth in preceeding weeks

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page xiv

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

controlling for dosage, has a greater impact on students’ longer-term literacy proficiency outcomes. Thus, a key

conclusion from our analysis is that early intervention from the MRC program (i.e., in the first semester) for struggling

students results in a higher likelihood of positive longer-term outcomes.

Final Thoughts

The Minnesota Reading Corps program is contributing to our nationwide goal of improving 3rd grade

reading proficiency.

In sum, the results of the Fall-Winter Experimental Study suggest that the MRC program produces the largest effects

most quickly with the youngest students, particularly Kindergarten students. The intensive one-on-one exposure to

MRC tutoring produces large increases in young students’ letter sound fluency. In later grades (i.e., second and

third), when students begin the more complex task of reading connected text, the MRC program may take longer to

produce larger effects in oral reading fluency. While it was not possible to experimentally examine the full-year impact

of the program on student outcomes in this study, the non-experimental analyses suggest that over the course of a

longer period of time, the MRC program could produce larger improvements in second and third grade students’ oral

reading fluency.

One of the most critical findings for program replication is MRC’s successful deployment of AmeriCorps members

lacking any specialized background in education or literacy. The results of the member analysis revealed no

significant differences in student impacts due to the characteristics of the members providing the tutoring. The lack of

member effects suggests that if similar program-based infrastructure and resources are provided and specialized

interventions are accurately implemented and closely monitored, members with diverse backgrounds can serve

without possessing any specialized prerequisite technical skills. The combination of MRC program elements that

resulted in positive impacts on student literacy outcomes can be considered an effective model for the development

of other successful reading intervention programs for K-3 students.

Given the smaller impacts found among older students, future research may wish to examine the impact of specific

MRC interventions on oral reading fluency, as well as the number and timing of changes in the use of these

interventions, to more fully explore which interventions may be more effective with older students. Additionally, it may

be of interest to follow these same randomized students through later school years to assess the potential long-term

effects of the MRC program on students’ performance on future benchmark assessments, meeting or exceeding

grade level proficiency on state literacy assessments, graduation rates, and other more distal educational and

economic outcomes.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page xv

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

I. Introduction

Minnesota Reading Corps (MRC) is a statewide initiative with a mission to help every Minnesota child become a

proficient reader by the end of third grade. MRC engages a diverse group of AmeriCorps members to provide literacy

enrichment and tutoring services to at-risk Kindergarten through third grade (K-3) elementary school students and

preschool children (PreK). As of the 2012-2013 school year, more than 1,100 AmeriCorps members implemented the

MRC program in 652 schools or sites

5F

6

and 184 school districts across the state of Minnesota.6F

7

This report, funded by the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS), describes the findings from a

randomized controlled trial (RCT) impact evaluation of over 1,300 K-3 students who were determined to be eligible

for the MRC program during the 2012-2013 school year. The students were enrolled at a representative sample of 23

schools that were experienced implementers of MRC programs. The goal of the impact evaluation was to determine

both the short- and long-term impacts of the MRC program on elementary students’ literacy outcomes. The K-3

impact evaluation is one of several complementary studies being completed on the MRC program: a process

assessment of the MRC program in 20 PreK and K-3 sites (completed in Spring 2013);

7F

8

a quasi-experimental impact

evaluation of the MRC PreK program on preschool students’ emergent literacy outcomes (forthcoming in Fall 2014);

and a survey of AmeriCorps members (Fall 2013). The impact evaluation focused on the following research

questions:

1. What is the impact of the MRC program on student literacy outcomes?

a. Does the impact vary by student characteristics/demographics?

b. Do assessment scores vary by AmeriCorps member characteristics/demographics?

2. Does the impact of the program vary week to week? Does the number of weeks of intervention (i.e., dosage)

impact student literacy outcomes?

3. Does participation in MRC have a longer-term impact on student literacy outcomes as measured at the end of

the school year?

To address these questions, we begin in Chapter II by presenting a brief overview of the MRC program and its role in

the recruitment, training, placement and monitoring of AmeriCorps members as they implement the program in

6

According to the Minnesota Department of Education (MDE), during the 2011-2012 school year, 942 public schools served grades K-12. Of

those schools, 912 offered PreK services. The total number of preschools in the state of Minnesota (i.e., public schools and non-public schools)

was not available. http://w20.education.state.mn.us/MDEAnalytics/Summary.jsp

7

According to MDE, during the 2011-2012 school year, there were 333 public operating elementary & secondary independent school districts,

3 intermediate school districts, and 148 charter schools (which are considered public school districts in Minnesota).

8

Hafford, C., Markovitz, C., Hernandez, M, et al. (February 2013). Process Assessment of the Minnesota Reading Corps Program. (Prepared

under contract to the Corporation for National and Community Service). Chicago, IL: NORC at the University of Chicago.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 1

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

preschool and elementary school settings. We then describe the K-3 component of the MRC program, which is the

focus of this evaluation, MRC’s multi-layered supervisory structure, and their Summer Training Institute. Chapter III

then provides information on the impact evaluation’s methodology for selecting sites and students, randomization

procedures for forming program and control groups for comparisons, collection and use of program data, and

analysis of findings.

This background information sets the context for the presentation of findings from the three analyses of assessment

data from the K-3 program in Chapters IV, V, and VI. Chapter IV provides the findings from the examination of the

shorter-term impacts of the program in our Fall-Winter Experimental Study. These findings are based on a

comparison of 16 weeks of data from the RCT program and control groups, during which control group students did

not receive any MRC services. Our examination of the program impacts also includes analysis of key subgroups,

including gender, race, Dual Language Learner (DLL) status, and Free and Reduced Price Lunch (FRPL) status. In

this chapter, we also examined whether impacts vary due to the characteristics of the AmeriCorps members who

conducted the tutoring or the schools where the tutoring took place.

In addition to the presentation of findings on the RCT results in Chapter IV, we provide in Appendix C a separate

analysis of the data tailored to the requirements of the U.S. Department of Education's Institute of Education

Sciences’ What Works Clearinghouse (WWC). We share the WWC’s goal to provide educators with the information

they need to make evidence-based decisions. Therefore, we have developed this appendix to specifically

demonstrate that our study meets WWC’s rigorous standards.

Chapter V provides the findings of results from the entire year of program data. This analysis includes data from all

students, including the control group students who were eligible to receive MRC services in the second semester of

the school year. For this Full Year Non-Experimental Study, we examined the effect of the program for each week of

tutoring and the cumulative effect over the school year both for the program group, which began receiving tutoring

earlier in the school year, and the control group, which included many students who received tutoring in the second

half of the school year.

The results presented in Chapter VI focus on the longer-term effects of the MRC program on students’ literacy

outcomes. Using two different exploratory analysis approaches, the evaluation team attempted to estimate the

longer-term probability of successfully maintaining proficiency after exiting the MRC program. For these analyses, we

used the entire year of weekly assessment data collected from both the program group, all of whom received

tutoring, and those control group students who received tutoring later in the school year.

We conclude our report in Chapter VII by returning to the research questions. The evaluation team addresses

whether the MRC K-3 program appears to have an impact on students’ literacy proficiency and whether there are

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 2

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

differential effects by grade, gender, race, DLL status, and/or FRPL status based on the findings from the Fall-Winter

Experimental Study. We also draw on the findings from the Full Year Non-Experimental Study to answer the

evaluation’s other key research questions on the week over week effects of the program and its longer-term impact

on students’ literacy outcomes. Finally, we discuss the implications of the findings for the MRC program. A glossary

of terms to assist the reader is provided in Appendix E.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 3

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

II. About Minnesota Reading Corps

A. Statewide Implementation of MRC: 2003-2013

Minnesota Reading Corps (MRC) is the largest AmeriCorps State program in the country. The goal of MRC is to

ensure that students become successful readers and meet reading proficiency targets by the end of the third grade.

The MRC program was started in 2003 to provide reading and literacy tutoring to children in four preschool (PreK)

Head Start programs. In 2005, MRC expanded its program to serve students in Kindergarten through third grade (K-

3). The core activities of MRC, and its host organization, ServeMinnesota Action Network, are to recruit, train, place

and monitor AmeriCorps members to implement research-based literacy interventions for at-risk K-3 students and

preschool children.

Minnesota Reading Corps is a strategic initiative of ServeMinnesota. ServeMinnesota is the state commission for all

AmeriCorps State programs in Minnesota, including the Minnesota Reading Corps, and helps leverage the federal,

state and private dollars to operate MRC. As a catalyst for positive social change and community service,

ServeMinnesota works with AmeriCorps members and community partners to meet critical needs in Minnesota. As a

nonprofit organization, it supports thousands of individuals to improve the lives of Minnesotans by offering life-

changing service opportunities that focus on education, affordable housing, employment, and the environment. The

ServeMinnesota Action Network serves as fiscal host to provide statewide management and oversight for the MRC

program. The Action Network is a nonprofit organization and serves as a home to incubate, replicate and scale

evidence-based AmeriCorps programs that address critical state priorities. In addition, the Saint Croix River

Education District (SCRED) and TIES have been funded by ServeMinnesota to conduct an annual evaluation of the

MRC program.

8F

9

AmeriCorps members in the MRC program serve in school-based settings to implement MRC literacy strategies and

conduct interventions with students. MRC members serve as AmeriCorps members, bound to the program’s call to

service. As a direct service program, MRC engages its members in service to work towards the solution of a social

issue. In exchange for their service of 1700 hours a year (full-time) or 900 hours a year (part-time), members receive

benefits that include a bi-weekly stipend, student loan forbearance, and an education stipend for the first two years of

service.

In addition to AmeriCorps members serving in the schools, the MRC model provides supports for maintaining the

fidelity of the intervention through the assignment of one or more Internal Coaches at each site or school to mentor

9

ServeMinnesota 2011, Background document.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 4

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

and guide members. Internal Coaches are typically specialists, teachers, or curriculum directors employed by the site

or school. Expert-level Master Coaches are also assigned to each Internal Coach to provide consultation on literacy

interventions and assessment, as well as ensure fidelity to the MRC model. The MRC Program Coordinators provide

administrative support to individual sites (Principals, Internal Coaches, and Master Coaches) and assist members

with their AmeriCorps responsibilities.

In the 2012-13 school year, the MRC program’s more than 1,100 AmeriCorps members served over 30,000 students

in 652 elementary schools, Head Start centers, and preschools, making it the largest AmeriCorps programs in the

country. Based on the early success of the MRC program, replication is underway in Colorado, Massachusetts,

Michigan, Santa Cruz County, CA, Washington DC, Virginia, Iowa, and North Dakota.

B. Foundational Framework and Staffing Structure in MRC

The MRC program utilizes a Response to Intervention (RtI) framework. The RtI model is based on a problem solving

approach which was incorporated into the 2004 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and has been

gaining popularity among educators, policymakers, administrators, teachers, and researchers. The key aspects of the

MRC RtI framework are:

■ Clear literacy targets at each age level from PreK through grade 3

■ Benchmark assessment three times a year to identify students eligible for one-on-one interventions

■ Scientifically based interventions

■ Frequent progress monitoring (formative assessment) during intervention delivery

■ High-quality training and coaching in program components, and literacy assessment and instruction

In the RtI framework, data play the key roles of screening students’ eligibility for additional services and then

monitoring students’ progress towards achieving academic goals (i.e., benchmarks). The Minnesota Reading Corps

screens students for program eligibility three times a year (i.e., Fall, Winter, Spring) with two sets of grade-specific,

literacy-focused general outcome measures (i.e., IGDI for PreK and AIMSweb for K-3) that possess criterion-

referenced grade- and content-specific performance benchmarks. Program staff use scores from these general

outcome measures to categorize students into one of three possible tiers (i.e., proficiency levels; see Figure II.1):

Tier 1 students score at or above benchmark and benefit from typical classroom instruction (75-80% of students

score in this category); Tier 2 students score below benchmark and require specific supplemental interventions until

they meet benchmarks (15-20% of students fall into this category); and Tier 3 students require intensive intervention

provided by a special education teacher or literacy specialist and often have individualized educational plans (5-10%

of students qualify for this category).

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 5

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Figure II.1. Minnesota Reading Corps Response to Intervention Tiers

The MRC K

-3 program provides one-on-one tutoring where members provide supplemental individualized literacy

interventions to primarily Tier 2 students in Kindergarten through third grade. Generally, those Tier 2 students who

score closest to the benchmark are offered MRC’s intervention services first because they should require the least

amount of intervention (i.e., time in program) to be set on a learning trajectory to achieve grade level proficiency. The

students closest to the benchmark can be moved through the program more quickly than those students with greater

need, allowing the schools to maximize support for students needing more intensive services. The MRC PreK

program includes both an immersive “push-in” component, where members provide whole-class literacy enrichment

for all students (i.e., Tier 1), and a targeted one-on-one component, where members provide individualized

interventions to students struggling with emergent literacy skills (i.e., Tiers 2 and 3). Although the MRC program

provides both PreK and K-3 interventions to students, the focus of this evaluation is on the MRC K-3 program.

Therefore, the remainder of this report will focus on describing the K-3 program and evaluation. As previously

mentioned, the findings from a quasi-experimental design (QED) evaluation of the PreK MRC program will be

available in Fall 2014.

Overview of K-3 Program Literacy Focus and AmeriCorps Members’ Role

At the K-3 level, the program is focused on the “Big Five Ideas in Literacy” as identified by the National Reading

Panel, including phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. AmeriCorps members

serve as one-on-one tutors and enact research-based interventions with students below grade-specific literacy

benchmarks (i.e., Tier 2 students). Full-time members individually tutor approximately 15-18 K-3 students daily for 20

minutes each. The literacy interventions consist of a set of prescribed, research-validated activities such as

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 6

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

“Repeated Reading with Comprehension Strategy Practice” or “Duet Reading.” The decision to change a student’s

interventions is based upon reviewing weekly progress monitoring data. The tutoring interventions are supplemental

to the core reading instruction provided at each school. The goal of the tutoring is to raise individual students’ literacy

levels so that they are on track to meet or exceed the next program-specified literacy benchmark. Meeting

benchmark will allow the student to benefit fully from general (i.e., Tier 1) literacy instruction already provided in the

classroom.

One variation among K-3 members is the Kindergarten-Focus (K-Focus) position. K-Focus members continue to tutor

students in grades Kindergarten through third; however, they tend to spend a majority of their time providing

Kindergarten students with a daily “double-dose” of MRC interventions. In the K-Focus program, each Kindergarten

student participates in two (20-minute) sessions daily, for a total of 40 minutes. One session is a 5-day Repeated

Read Aloud intervention that is conducted in a small group setting (typically four students) that includes dialogic

reading to focus on phonemic awareness, phonics, and vocabulary instruction. The other session is a standard MRC

early literacy intervention that is selected by the Internal Coach based on student needs (phoneme blending,

phoneme segmenting, letter sounds or word blending) and is conducted in pairs of students.

Supervisory Staff

The Internal Coaches and Master Coaches play important roles in MRC program implementation (see Figure II.2 for

an illustration of the complete MRC supervisory structure). The Internal Coach is a school employee who is trained to

provide on-site literacy support and oversight to AmeriCorps members serving as literacy tutors at the site. In order to

ensure fidelity to the MRC model, the Internal Coach conducts monthly integrity checks for each intervention and

scores the member using the Accuracy of Implementation Rating Scale (AIRS) before each benchmarking period.

The Internal Coach provides the member with feedback based on these observations. The Internal Coach also

ensures that the member is accurately reporting student data in AIMSweb and OnCorps. Throughout the school year,

the Internal Coach works with assistance from the Master Coach to select appropriate interventions for each student

and to determine if students are ready to exit the program. The Internal Coach also works closely with MRC program

staff and school administration to address any concerns about member performance and to address disciplinary

action if necessary. MRC estimates that the time commitment for Internal Coaches is 6-9 hours per member per

month. The additional time commitment for required training is 32 hours for new K-3 Internal coaches and 16 hours

for returning K-3 Internal coaches.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 7

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

Figure II.2. MRC Supervisory Structure

The Mas

ter Coach is a literacy expert employed by MRC who serves as a literacy consultant to the Internal Coach

and member(s). The Master Coach supports the Internal Coach and the member in making decisions about student

eligibility and instruction by reviewing benchmark data. The Master Coach also helps to ensure fidelity to the MRC

model. The Master Coach visits schools at different frequencies throughout the year depending on the schools’

degree of experience implementing MRC, ranging from once a month for schools that have recently implemented

MRC to three times a year for schools where MRC is well-established. Visits last approximately one hour per

member, during which the Master Coach, Internal Coach and member(s) discuss students’ assessment data,

progress towards achieving benchmark goals, and implementation challenges.

Other Master Coach responsibilities include communicating with the Internal Coach and member(s) about preparing

for benchmarking; performing member fidelity checks along with the Internal Coach to ensure appropriate

administration of benchmark assessments and interventions; providing consultation as needed regarding the

identification and prioritization of students to receive MRC tutoring; reviewing student progress monitoring graphs;

and providing program updates to the Internal Coach and member. If the Internal Coach cannot answer a member’s

question, the Master Coach can often provide advice. The Master Coach can also answer questions about topics

such as AIMSweb or scheduling.

For administrative issues, such as questions about training schedules and timesheets, the Internal Coach or member

can contact their MRC Program Coordinator. The Program Coordinator also helps members answer questions about

their community service requirement and requested leaves of absence. Program Coordinators also are to be notified

about all member disciplinary issues.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 8

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

C. Summer Institute Training

Each summer, the Minnesota Reading Corps hosts a multi-day Summer Institute for training returning and new

Master Coaches, Internal Coaches, and AmeriCorps members.

9F

10

ServeMinnesota and MRC staff orchestrates the

organizational and administrative aspects of the Summer Institute, while Minnesota literacy experts conduct training

sessions. This intensive, information-filled conference provides expert training in the research-based literacy

interventions employed by MRC. In its most basic form, the Summer Institute is a learning forum for literacy

interventions and teaching techniques. However, the Summer Institute also serves an important role in developing

member, coach, and eventually, school adherence to the MRC model. Speeches from former and current members,

funders, parents, and officials from the Minnesota Department of Education and local school districts encourage this

process and enhance the inspirational atmosphere of the training sessions. At the Summer Institute, the members

also meet with their Internal Coach, and sometimes Master Coach, with whom they will be working throughout the

upcoming school year.

During several intensive sessions at the Summer Institute, members learn the essential skills, knowledge, and tools

needed to serve as effective literacy tutors. These sessions introduce members to the MRC program model, the

interventions that constitute the instructional core of the program, as well as the underlying research and theories

supporting the interventions and program model. Importantly, members are provided with detailed Literacy

Handbooks to serve as a resource for supporting program implementation. The handbooks provide an introduction to

the MRC program, information on policies and procedures and service requirements, procedures for the

benchmarking and progress monitoring of students, and specific direction and materials for conducting MRC

strategies and interventions. In addition, members are provided with online resources that mirror the contents of the

Literacy Handbook and supplement it with other resources such as videos of model interventions and best practices.

Both the Handbook and website are intended to provide members with just-in-time support, as well as opportunities

for continued professional development and skill refinement.

At the Summer Institute, K-3 AmeriCorps members are trained to provide the MRC research-based, reading

interventions that help K–3 students reach grade-level literacy benchmarks. K-3 members are trained how to

implement the majority of instructional interventions during the Summer Institute. However, members also participate

in two additional trainings early in the fall where they learn to use the assessment tool, AIMSweb, and Great Leaps, a

comprehensive intervention for struggling readers that focuses on sound awareness (phonological/ phonemic

awareness), letter recognition and phonics, high frequency sight words and phrases, and stories for oral reading.

10

Members attend all four days of the Summer Institute (one day orientation and three days of training). New Coaches attend three days, and

returning Coaches attend one day.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 9

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

In addition to member training, at the Summer Institute each Internal Coach receives a comprehensive orientation to

MRC, including program and early literacy background, intervention delivery, benchmarking and progress monitoring.

At their training sessions, Internal Coaches also receive information about their roles, responsibilities and

expectations while serving in the program. The Internal Coaches are instructed in their responsibilities, including

ensuring fidelity to the MRC model, orienting the member to the school, introducing school staff to the member,

setting the tutoring schedule and coordinating school-based professional development opportunities for their

members. Internal Coaches also are oriented to the layers of support provided by MRC, including the Master Coach

and Program Coordinator.

D. The Role of Data in MRC Program Implementation and Improvement

In the Fall, Winter, and Spring of each school year, AmeriCorps members collect general outcome measure data

using the AIMSweb literacy assessments. The AIMSweb assessments evaluate three critical literacy skills that

research of literacy development has confirmed are appropriate for specific grade levels and seasons: 1) letter sound

fluency (Kindergarten), 2) nonsense word fluency (first grade –Fall/Winter), and 3) oral reading fluency (first grade –

Winter/Spring, second and third grades). These assessments are collectively called curriculum-based measures

(CBM), because they correspond closely with curricular expectations for literacy skills at each developmental level.

For example, literacy expectations for Kindergarten students focus on learning the phonetic relationships that exist

between letters and sounds. As students progress through elementary school, they learn more complex (i.e. word-

level) relationships between letters and sounds, and over time they are expected to demonstrate fluent reading of

connected text. These expectations are broadly accepted by literacy experts and are reflected in such documents as

the Common Core State Standards. The CBM measures used by MRC were developed to assess each of these

skills, and extensive research has shown them to be sufficiently reliable and valid for making decisions within an RTI

framework (see Appendix C for a description of the psychometric properties of outcome measures) .

Table II.1 lists the specific AIMSweb CBM assessments and corresponding benchmark scores used to identify

program eligible K-3 students by grade and season. These benchmark scores correspond to empirically-derived

target scores that, through large-scale research studies, indicate the level of literacy skill that needs to be

demonstrated in a certain grade at a certain time period to have a 90% chance of passing a high-stakes state reading

assessment in third grade. For example, in order for a second grade student to have at least a 90% chance of

demonstrating proficiency on their future third grade reading proficiency assessment, they need to have a score of at

least 42 on the Fall benchmark and at least 73 on the Winter benchmark in the oral reading fluency CBM.

These data are used in the Fall benchmark data collection period to identify students who are in need of MRC

support. Given the sometimes large student to AmeriCorps member ratio at participating schools, the Internal Coach

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 10

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

typically prioritizes which students the members will assess using existing school data. Generally, Internal Coaches

prioritize students who previously received MRC services, and any student the Internal Coach believes may benefit

from MRC services. Members assess these students, and Internal Coaches review this data to then objectively

determine eligibility based upon their benchmark score. Once selected to receive services, members collect weekly

progress monitoring data using CBM assessments that are appropriate for their grade level.

Table II.1. MRC K-3 CBM assessments and benchmarks by grade and season

Assessment

Fall Target

Winter Target

Spring Target

Kindergarten Letter Sound Fluency 10 21 41

1

st

Grade

Nonsense Word Fluency

32

52

n/a

Oral Reading Fluency n/a 22 52

2

nd

Grade Oral Reading Fluency 42 73 90

3

rd

Grade

Oral Reading Fluency

70

91

109

The MRC program uses the OnCorps and AIMSweb internet-based data entry systems to record and store general

outcome measure and progress monitoring data on all students served by the program. Progress monitoring allows

members to chart student progress, assess effectiveness of current interventions, gauge if students require a change

in interventions, or determine if they are ready to exit the program. Every student’s progress monitoring scores are

graphed and then reviewed monthly by a collaborative team consisting of the members, Internal Coach and Master

Coach. In the K-3 program, Tier 2 students receive intervention services until their progress monitoring data shows

that they have achieved 3 to 5 consecutive data points above the aimline (i.e., projected growth trajectory) and two

scores at or above the upcoming season benchmark target. Similar criteria are used for the discontinuation of

services with Kindergarten students, although the Spring rather than Winter target is used to determine eligibility for

all seasons. Once these criteria are met, a student is deemed “on-track” to achieve appropriate grade-level

benchmark at the next assessment window, and is “exited” from the MRC program (i.e., the member no longer

provides intervention services). The Master Coach, Internal Coach, and AmeriCorps member discuss each student’s

assessment results over time before deciding to exit the student from service.

The data intensive orientation of the MRC program provides members, coaches, teachers and principals/directors

with a consistent, objective means of identifying students to receive program services, tracking their progress toward

achieving academic goals related to critical literacy skills, and informing instruction. The assessment data play an

important role in garnering site-wide support from non-MRC-affiliated site staff, particularly as they see quantitative

improvement in student outcomes. The data also provide members and coaches with objective information about the

efficacy of the interventions with individual students, which can in turn be used to tailor the most effective instruction

for the student’s skill level.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE MINNESOTA READING CORPS K-3 PROGRAM Page 11

The Corporation for National and Community Service | 2014

In addition to using assessment data to identify individual students for services and to inform instruction, the MRC

program also uses data to evaluate and improve the program itself. This continued investment in research and

development has led to a number of examples of innovations and program improvements at the systems level. For