Charles R. Breyer

Acting Chair

Patricia K. Cushwa

Ex Ofcio

Jonathan J. Wroblewski

Ex Ofcio

Kenneth P. Cohen

Staff Director

Glenn R. Schmitt

Director

Ofce of Research and Data

August 2022

United States Sentencing Commission

One Columbus Circle, N.E.

Washington, DC 20002

www.ussc.gov

Kathleen C. Grilli, J.D.

General Counsel

Kevin T. Maass, M.A.

Research Associate

Charles S. Ray, J.D.

Assistant General Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

INTRODUCTION

2

KEY FINDINGS

4

CHAPTER 1: THE SENTENCING REFORM ACT AND ITS STATUTORY

MANDATE TO DEVELOP ORGANIZATIONAL GUIDELINES

12

CHAPTER 2: ORGANIZATIONAL SENTENCING DATA

42

CHAPTER 3: INFLUENCE OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL SENTENCING

GUIDELINES

50

CONCLUSION

51

APPENDICES

70

ENDNOTES

i

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

INTRODUCTION

As ultimately promulgated in

1991, the guidelines in Chapter Eight

of the Guidelines Manual represented

a collaborative process between the

United States Sentencing Commission

("Commission"), federal agencies,

businesses, industry advocacy groups,

academia, and many other stakeholders.

The organizational guidelines reect a set

of principles identied during this process

and incorporated into the guidelines to

achieve the goals of the Sentencing Reform

Act of 1984 ("SRA") and address the

concerns raised by Congress. Although

initially resisted by some commentators,

the organizational guidelines have since

been embraced for their innovative

approach to organizational sentencing: (1)

incentivizing organizations to self-police

their behavior; (2)providing guidance on

effective compliance and ethics programs

that organizations can implement to

demonstrate efforts to self-police; and

(3)holding organizations accountable

based on specic factors of culpability.

The organizational sentencing

guidelines have wielded signicant

inuence on corporate America. Chapter

Eight was designed to incentivize corporate

self-policing through its "carrot and stick"

philosophy

1

and it has "catalyzed vigorous

efforts by companies to promote ethical

performance and reduce organizational

misconduct."

2

Thirty years have elapsed

since their original promulgation and the

hallmarks for an effective compliance and

ethics program found in the guidelines

continue to set the gold standard for

designing and evaluating effective

compliance and ethics programs.

3

This publication summarizes the

history of Chapter Eight's development

and discusses the two substantive changes

made to the elements of an effective

compliance and ethics program. It then

provides policymakers and researchers

a snapshot of corporate sentencing over

the last 30 years. Finally, the publication

describes Chapter Eight's impact beyond

federal sentencing.

1

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

KEY FINDINGS

2

United States Sentencing Commission

1

The major innovations of the

organizational guidelines are

(1) incentivizing organizations

to self-police their behavior; (2)

providing guidance on effective

compliance and ethics programs

that organizations can implement to

demonstrate efforts to self-police; and

(3)holding organizations accountable

based on specic factors of culpability.

2

The most signicant

achievement of Chapter Eight

has been the widespread

acceptance of the organizational

guidelines' criteria for developing and

maintaining effective compliance and

ethics programs to prevent, detect, and

report criminal conduct.

3

During the 30-year period

since promulgation of the

organizational guidelines,

4,946 organizational offenders have

been sentenced in the 94 federal

judicial districts. The majority of

organizational offenders are domestic

(88.1%), private (92.2%), and smaller

organizations with fewer than 50

employees (70.4%).

4

Six offense types accounted

for 80.4 percent of all

organizational offenders from

scal years 1992 through 2021.

• Fraud (30.1%) and environmental

(24.0%) offenses, accounted

for more than half (54.1%) of all

organizational offenses.

• Other common offense types were

antitrust (8.4%), food and drug

(6.6%), money laundering (6.1%),

and import and export crimes (5.2%).

3

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

5

Commission data suggests

that the lack of an effective

compliance and ethics program

may be a contributing factor to criminal

prosecutions against organizations.

• Since scal year 1992, the

overwhelming majority of

organizational offenders (89.6%) did

not have any compliance and ethics

program.

• Only 11 of the 4,946 organizational

offenders sentenced since scal year

1992 received a culpability score

reduction for having an effective

compliance and ethics program.

• More than half (58.3%) of the

organizational offenders sentenced

under the ne guidelines received

a culpability score increase for

the involvement in or tolerance of

criminal activity.

• Few organizational offenders (1.5%

overall) received the ve-point

culpability score reduction for

disclosing the offense to appropriate

authorities prior to a government

investigation in addition to their

full cooperation and acceptance of

responsibility.

• Since scal year 2000, courts

ordered one-fth (19.5%) of

organizational offenders to

implement an effective compliance

and ethics program.

6

Since scal year 1992,

the courts have imposed

nearly $33 billion in nes on

organizational offenders. The average

ne imposed was over $9 million and

the median amount was $100,000.

7

Since scal year 1992, courts

sentenced over two-thirds

of organizational offenders

(69.1%) to a term of probation and the

average length of the term of probation

imposed was 39 months.

CHAPTER ONE

4

United States Sentencing Commission

T S R A S M

D O G

One of the primary motivations for

the SRA was to eliminate unwarranted

disparity in sentencing and to address

the inequalities created by unfettered

sentencing discretion.

4

While much of

the Congressional concern focused on

individual sentencing, the Senate report

accompanying the SRA also detailed

Congress's observations regarding the

sentencing of organizations. It stated that

The Senate report also noted concerns

that white collar criminals were being

sentenced to minimal nes, creating "the

impression that certain offenses are

punishable only by a small ne that can be

written off as a cost of doing business."

6

As part of the SRA, Congress created

the Commission as an independent

agency within the judicial branch of the

federal government and tasked it with

the responsibility of developing federal

sentencing policy.

7

The SRA directed the

Commission to promulgate guidelines

that federal judges would use for selecting

sentences within the prescribed statutory

range.

8

The SRA also specied that an

organization

9

may be sentenced to a term

of probation

10

or a ne, or a combination

of these sanctions,

11

and required that

"[a]t least one of such sentences must be

imposed."

12

Additionally, the SRA made

clear that an organization could "be made

subject to an order of criminal forfeiture,

an order of notice to victims, or an order of

restitution."

13

[c]urrent law . . . rarely

distinguishes between

individuals and organizations for

sentencing purposes[;] [t]hus,

present law fails to recognize

the usual differences in the

nancial resources of these two

categories of defendants and

fails to take into account the

greater nancial harm to victims

and the greater nancial gain to

the criminal that characterizes

offenses typically perpetrated by

organizations.

5

5

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

H O G

On October 1, 1986, the Commission

published in the Federal Register the

Preliminary Draft of the Sentencing

Guidelines.

17

This draft laid out two

possible approaches to the development of

organizational sanctions based on the just

punishment and deterrence philosophies.

The just punishment approach emphasized

an organization's culpability

18

and its

ability to pay a ne, while the deterrence

approach focused on the harmfulness of an

organization's conduct and the likelihood

of detection of the crime.

19

Noting the

competing concerns raised by the just

punishment and deterrence purposes,

20

the Commission sought public comment

on "whether its approach to nes should

emphasize the organization's culpability

and ability to pay, or the harmfulness of its

conduct and the likelihood of detection."

21

The Commission also identied the

mandatory and discretionary conditions

of probation authorized by statute,

22

and it sought comment about the types

of probation conditions that might be

imposed on an organization and the

circumstances justifying their imposition.

23

Original Organizational Guidelines

Consistent with its statutory mandate

and the observations of Congress,

the Commission began exploration of

guidelines for use by federal courts to

sentence organizations convicted of

a federal offense. The initial Chapter

Eight organizational guidelines were the

product of an extensive multiyear process

conducted by the Commission.

14

The

Commission held its rst public hearing

devoted exclusively to consideration of

organizational sanctions in June 1986

15

and continued to solicit and consider

public comment from many stakeholders,

including from the U.S. Departments

of Justice ("DOJ"), Treasury, Defense,

Education, Health and Human Services,

Interior, and Labor, the Federal Deposit

Insurance Corporation, the U.S. Postal

Service, and the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission ("SEC") about

offenses occurring within their areas of

responsibility.

16

6

United States Sentencing Commission

Because of the complexity of the

subject matter and tight deadlines imposed

by the SRA,

24

the Commission deferred

action on the organizational guidelines until

completion of the guidelines for individual

defendants.

25

Shortly after delivery of

the rst Guidelines Manual to Congress,

26

the Commission turned its attention back

to corporate sanctions. In July 1988, the

Commission published the Discussion

Materials on Organizational Sanctions to

gather comment and analysis on the

development of sentencing standards

for organizations.

27

Those materials

included a Commission staff working

paper on organizational sentencing policy

recognizing that "[t]he key to an effective

organizational sentencing system lies in

selecting penalty rules that will provide

organizations with the most desirable

incentives for their compliance efforts."

28

Two Commission hearings followed

the release of the Discussion Materials on

Organizational Sanctions.

29

Witnesses,

including representatives from the

President's Council of Economic Advisers,

staff from the SEC, Environmental

Protection Agency ("EPA"), Food and Drug

Administration, the U.S. Probation Ofce,

the Institutional Shareholders Services,

academics, and others,

30

testied on the

importance of internal corporate controls

as a means of deterring organizational

crime and supported involving the

organization in the development of a

compliance plan.

31

During these hearings

the discussion of compliance programs as a

mitigating factor rst arose,

32

an idea that

attracted the Commission's interest.

33

In 1988, the Commission formed a

working group of private defense attorneys

to develop a set of practical principles for

sentencing organizations.

34

In its May

1989 report, Recommendations Regarding

Criminal Penalties for Organizations,

the working group asserted that

organizational sanctions should serve dual

purposes: punishment and deterrence by

incentivizing organizations to take steps to

prevent crimes.

35

The report also identied

a number of factors that should ameliorate

the criminal ne amount.

36

On November 8, 1989, the Commission

published for public comment a set of

proposed organizational sentencing

guidelines as a new chapter to the

Guidelines Manual: Chapter Eight—Sentencing

of Organizations that provided for ne

reductions for compliance efforts in

certain circumstances.

37

The Commission

held public hearings on the published

7

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

proposed guidelines.

38

Witnesses from a

broad spectrum of special interest groups,

including the National Association of

Manufacturers, the American Corporate

Counsel Association, the U.S. Chamber

of Commerce, and the American

Bar Association ("ABA"), along with

representatives from federal agencies,

academics, and the general counsels of

various private businesses, testied about

the elements of successful compliance

programs, among other subjects.

39

Ultimately, the Commission came to the

consensus that staff should develop draft

guidelines to reect self-policing through

economic incentives as an alternative to

the previous draft guidelines.

40

Although the Commission

had anticipated promulgating the

organizational guidelines at its meeting

on April 10, 1990, the matter was

deferred until after the appointment

of new members.

41

Once three new

commissioners were sworn in on July

24, 1990, the now fully constituted

Commission agreed on a set of general

principles to be used in drafting guidelines

on organizational sanctions.

42

These

principles included incentives for

organizations to minimize the likelihood

of criminal behavior and ensure that, if

detected, such wrongdoing would be

reported by the organizations.

43

On November 5, 1990, the Commission

published for comment proposed

organizational guidelines.

44

The draft

dened the requirements of an effective

compliance program, making clear that the

hallmark of such programs is the exercise

of the organization's due diligence to

prevent and detect criminal conduct by

its agents, and recognized such programs

as a mitigating factor for a ne reduction

of the applicable ne range. The draft

also provided that an organization would

not ordinarily qualify for the effective

compliance program mitigating factor

unless it also qualied for the mitigating

factor, which required that no compliance

personnel or person with substantial

managerial authority knew about the

violation.

45

On December 13, 1990, the

Commission held a nal public hearing

on the organizational guidelines.

46

The

witnesses generally favored including an

effective compliance program as one of the

mitigating factors and believed that giving

credit for an effective compliance program

would deter future criminal activity.

47

Several witnesses expressed the view

8

United States Sentencing Commission

that the Commission correctly identied

the essential elements of an effective

compliance program in the published

commentary.

48

After further renement to the

published draft, the Commission

unanimously voted to promulgate the

organizational guidelines and submit

them to Congress for a 180-day review

period.

49

The newly promulgated Chapter

Eight, titled "Sentencing of Organizations,"

took effect on November 1, 1991.

50

The

Commission expressed the aspiration

that "organizations would come to view

this guideline scheme as a powerful

nancial reason for instituting effective

internal compliance programs that, in

turn, would minimize the likelihood that

the organization would run afoul of the

law in the rst instance."

51

Moreover, if

a corporate crime was committed, "the

sentencing guideline incentives would

drive the corporate actor toward swift and

effective disclosure and other remedial

actions."

52

General Principles Embodied in

Chapter Eight of the Guidelines

Manual

The Chapter Eight guidelines and

policy statements reect several general

principles relating to the sentencing

of organizations. The guidelines are

"designed so that the sanctions imposed

upon organizations and their agents, taken

together, will provide just punishment,

adequate deterrence, and incentives

for organizations to maintain internal

mechanisms for preventing, detecting,

and reporting criminal conduct."

53

"First,

the court must, whenever practicable,

order the organization to remedy any

harm caused by the offense . . . as a means

of making victims whole for the harm

caused."

54

Second, any organization that

operated primarily for a criminal purpose

or by criminal means should receive a ne

sufciently high to divest the organization

of all its assets.

55

"Third, the ne range for

any other organization should be based

on the seriousness of the offense and the

culpability of the organization."

56

"The

seriousness of the offense generally will be

reected by the greatest of the pecuniary

gain, the pecuniary loss, or the amount

in a guideline offense level ne table."

57

"Culpability generally will be determined by

six factors that the sentencing court must

consider."

58

The four aggravating factors

are: "(i) the involvement in or tolerance

of criminal activity; (ii) the prior history

of the organization; (iii) the violation

of an order; and (iv) the obstruction of

justice."

59

"The two factors that mitigate

the ultimate punishment of an organization

are: (i) the existence of an effective

The guidelines are "designed so

that the sanctions imposed upon

organizations and their agents,

taken together, will provide just

punishment, adequate deterrence,

and incentives for organizations

to maintain internal mechanisms

for preventing, detecting, and

reporting criminal conduct."

9

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

compliance and ethics program; and (ii)

self-reporting, cooperation, or acceptance

of responsibility."

60

Finally, probation is an

appropriate sentence for an organization

"when needed to ensure that another

sanction will be fully implemented, or to

ensure that steps will be taken within the

organization to reduce the likelihood of

future criminal conduct."

61

Evolution of Chapter Eight

The structure of Chapter Eight and

its general principles have remained

largely unchanged since its original

promulgation. Nevertheless, after initial

promulgation, commentators offered

suggestions for amendments to Chapter

Eight.

62

After the President nominated

and the Senate conrmed seven new

commissioners in 1999, the Commission

developed an interest in re-examining

Chapter Eight.

63

Judge Diana E. Murphy,

the new Commission Chair, and the

other commissioners "became aware

of the wide impact the [organizational]

[g]uidelines have on organizations . . .

extend[ing] far beyond their use in the

context of criminal cases."

64

Under Chair

Murphy, the Commission began to consider

whether ethics was "an implicit component

of effective compliance programs, or

whether ethics should now explicitly be

incorporated into the compliance program

criteria in the organizational guidelines."

65

In 2001, in light of the public comment

it received regarding the organizational

guidelines, the Commission solicited

public input on the formation of an ad hoc

advisory group to identify any changes

needed to improve their operation.

66

Informed by the response, the Commission,

on February 21, 2002, formed an ad hoc

advisory group to review the organizational

guidelines with particular emphasis on

examining the criteria for an effective

program to ensure compliance with the

law by an organization.

67

The 15-member

group was composed of industry

representatives, scholars, and experts in

compliance and business ethics.

68

Five months after the Commission

created the advisory group, Congress

enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.

69

Section 805 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

directed the Commission to "review

and amend, as appropriate, the Federal

Sentencing Guidelines and related policy

statements to ensure that . . . the guidelines

that apply to organizations in United

States Sentencing Guidelines, [C]hapter

[Eight], are sufcient to deter and punish

organizational criminal misconduct."

70

The

Commission used the advisory group's

work to inform its response to that

directive.

The advisory group sought public

comment on the organizational guidelines

71

and identied its primary focus on the

criteria for an effective compliance

program and how those criteria affected

the operation of Chapter Eight as a whole.

72

The advisory group received signicant

10

United States Sentencing Commission

public interest to both its initial and a

subsequent request for comment.

73

A

public hearing on November 14, 2002, with

testimony from witnesses with a broad

range of perspectives, further informed the

advisory group's work.

74

On October 7, 2003, the advisory

group presented a comprehensive report

to the Commission on possible changes

to the organizational guidelines.

75

The

report concluded that the organizational

sentencing guidelines were successful

in encouraging organizations to develop

compliance programs to prevent and

detect wrongdoing, but recommended

greater guidance regarding the factors

for an effective program.

76

Specically, the

advisory group recommended that the

Commission promulgate a stand-alone

guideline dening effective compliance

programs and make changes to the

denitions and requirements of such

programs.

77

Informed by the public comment

78

and

hearing testimony,

79

the Commission on

April 8, 2004, unanimously promulgated

an amendment that elevated the criteria

for an effective compliance program

from commentary into a separate

guideline, §8B2.1 (Effective Compliance

and Ethics Program).

80

The amendment

also strengthened the existing criteria

by, for example, requiring organizations

to establish standards and procedures

to prevent and detect criminal conduct,

more precisely dening the oversight

responsibilities of the organization's

governing authority, and making

compliance and ethics training a

requirement, specically extending the

training requirement to the upper levels

of an organization.

81

The amendment

added a requirement to conduct periodic

risk assessments as a condition of

probation.

82

The amendment also added

the requirement that organizations

"otherwise promote an organizational

culture that encourages ethical conduct

and a commitment to compliance with the

law."

83

The Commission also took steps to

address concerns regarding the lack of

incentives for small organizations to

develop compliance programs.

84

First,

the Commission provided additional

guidance regarding the implementation of

compliance and ethics programs by small

organizations.

85

Next, the commentary

T O G

Initial Promulgation

Oct. 1986

Nov. 1989

Nov. 1990

Nov. 1991

Preliminary draft of

Guidelines solicits comment

on organizational sanctions

Publication of proposed

Organizational Guidelines

Chapter Eight became

effective

11

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

encouraged larger organizations to

promote the adoption of compliance and

ethics programs by smaller organizations

with which they conducted business.

86

The

Commission also replaced the automatic

preclusion for compliance program credit

provided at §8C2.5(f) with a rebuttable

presumption to allow smaller organizations

to argue for a culpability score reduction

based upon an effective compliance

and ethics program.

87

The amended

organizational guidelines became effective

on November 1, 2004.

The Commission considered

further changes during the 2009–2010

amendment cycle. Mindful of the fact

that "even modest changes to the

Guidelines can have a huge impact on the

compliance and ethics activities in virtually

every organization,"

88

the Commission

actively solicited input on the proposed

amendment

89

from groups known to have

an interest in Chapter Eight. As a result,

the Chapter Eight proposed amendment

received more public comment than any

other proposed amendment in 2010.

90

Commentators included government

agencies, including the Departments

of Health and Human Services, and

Commerce,

91

the Commission's standing

advisory groups,

92

ethics and compliance

industry professionals, for example, the

Society of Corporate Compliance and

Ethics ("SCCE"), the Ethics and Compliance

Ofcers Association, and the Ethisphere

Institute,

93

and non-prot research

organizations, such as the Ethics Resource

Center and Washington Legal Foundation.

94

After considering the voluminous

comments

95

and hearing testimony,

96

the

Commission expanded the scope of the

culpability score reduction at §8C2.5(f)

to make it available to organizations of all

sizes and claried certain requirements

needed for an effective compliance and

ethics program.

97

The amendment also

added an application note describing the

"direct reporting obligations" necessary

to meet the rst criterion under §8C2.5(f)

(3)(C) and provided encouragement, by

means of potential sentence mitigation, for

organizations to adopt "compliance and

ethics policies that provide operational

compliance personnel with access to the

governing authority when necessary."

98

The amended organizational guidelines

became effective on November 1, 2010.

99

Amendments

July 2002

Nov. 2004

Nov. 2010

Sarbanes-Oxley Act to review

and amend Chapter Eight

Amendments to Chapter Eight

elevating and strengthening the

criteria for an effective compliance

program become effective

Amendment to §8B2.1

became effective

12

United States Sentencing Commission

CHAPTER TWO

O S D

Introduction

Because criminal prosecutions resulting

in a sentencing are only one method by

which an organization's violations of the

law can be addressed by the authorities,

100

Commission sentencing data cannot fully

measure the prevalence of corporate

crime.

101

Nevertheless, by providing a

snapshot of organizational offenders

and offenses, this data may inform

policymakers and researchers regarding

the trends in corporate sentencing and

may also contribute to the continuing

dialogue about the importance of effective

compliance and ethics programs and

identify areas for further renement in

existing programs.

Methodology

The Commission's organizational

datale consists of information about

organizations that have been convicted and

sentenced for a federal criminal offense.

102

From the court documents submitted, the

Commission collects information including

company demographic information (e.g.,

size, business classication), guideline

application, and the details of the sentence

such as nes and restitution. This report

provides information on organizational

offenders sentenced between scal year

1992 and scal year 2021. However,

because the process to collect this data has

changed over this time, not all analyses can

be presented for the entire period.

13

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Organizational Offenders

During the 30-year period since

promulgation of the organizational

guidelines, 4,946 organizational offenders

have been sentenced in the 94 federal

judicial districts.

103

This compares to nearly

two million individual federal offenders

sentenced within the same period.

104

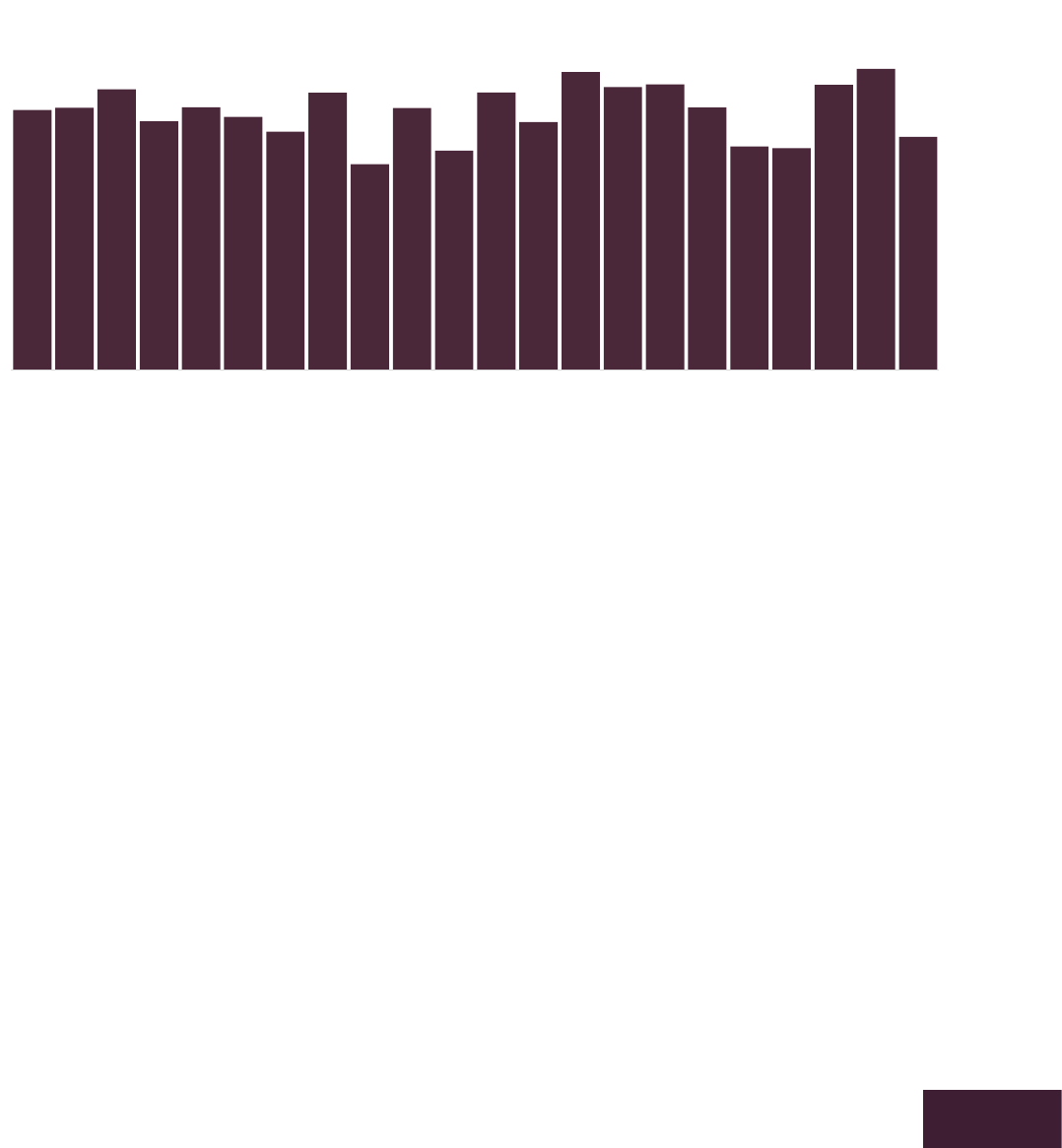

The Commission observed a fairly

steady increase in the number of

organizational offenders from scal year

1992 to scal year 2000. As demonstrated

in Figure 1, courts sentenced 18

organizational offenders in scal year

1992, compared to a high of 304 offenders

in scal year 2000. From this peak in scal

year 2000, the number of organizational

offenders has gradually declined to below

100 in the most recent two scal years.

Organizational offenders represent a

small proportion of all federal offenders

(0.2% in scal year 2021). Although

organizational offenders have sentencing

trends distinct from those of individual

offenders, the Commission has also

observed a decline in the number of

individual offenders sentenced since the

reported high in scal year 2011 through

the current scal year.

105

18

69

104

120

162

222

220

255

304

238

252

200

130

187

217

197

199

177

149

160

187

172

162

181

132

131

99

118

94

90

Figure 1. Number of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

14

United States Sentencing Commission

In scal year 2000, the Commission

expanded its data collection to record

whether an organization was a domestic

or foreign organization. The majority

of organizational offenders (88.1%) are

domestic organizations. The highest

Figure 2. Percentage of Domestic Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

percentage of domestic organizations was

reported in scal year 2001 (96.2%) (Figure

2). Since then, the proportion of domestic

organizations has been gradually declining,

with the lowest rate (78.1%) reported in

scal year 2017.

96.0%

96.2%

93.6%

91.1%

91.8%

91.4%

95.3%

92.9%

90.6% 90.6%

81.0%

88.4%

84.4%

82.4%

82.1%

78.3%

81.8%

78.1%

81.8%

78.7%

81.5%

82.2%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

15

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Ownership Structure

The Commission also collects

information about the ownership structure

of organizational offenders. Although the

Commission has revised the categories

of ownership structure of organizational

offenders over time,

106

these ownership

structures can be grouped within the

following ve broad categories: private

organization,

107

public organization,

108

non-prot organization,

109

governmental

organization,

110

and other organization.

111

The overwhelming majority of

organizations were private organizations

(92.2%) (Figure 3). The next most common

ownership structure was the public

organization (4.8%).

Figure 3. Ownership Structure of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

Private

Organization

92.2%

Public Org

4.8%

Non-Profit

Org

0.8%

Gov't Org

0.6%

Other Org

1.6%

16

United States Sentencing Commission

Size of Organization

The majority (70.4%) of organizational

offenders sentenced are smaller

organizations with fewer than 50

employees (Figure 4). Organizations with

50-to-99 employees (9.4%) and 100-to-

Figure 4. Size of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

< 50 Employees

70.4%

50-99 Employees

9.4%

100-499 Employees

12.1%

500-999 Employees

1.7%

≥ 1000 Employees

6.4%

499 employees (12.1%) were the next most

common organizational sizes. Less than ten

percent (8.1%) of organizations had greater

than 500 employees.

17

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Financial Status at Sentencing

The criminal prosecution and

sentencing of an organization may

impact its nancial status. The stigma

of a criminal conviction may drive away

an existing or potential customer base,

thereby threatening the organization's

ability to survive. Moreover, organizational

sentences typically include monetary

sanctions, such as restitution and nes.

These monetary sanctions may cause

additional nancial stress to an already

vulnerable organization. To understand

these effects, the Commission collects data

on the organization's nancial status at the

time of sentencing.

With few exceptions, the majority

(64.5%) of organizations sentenced each

scal year remained solvent and operating

at the time of sentencing (Figure 5).

However, approximately 30 percent were

either defunct (17.6%) or in nancial stress

(13.0%) at the time of sentencing.

Figure 5. Financial Status of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

Defunct

17.6%

Solvent

64.5%

Bankrupt

(Ch. 7)

0.7%

Reorganization

(Ch. 11)

1.2%

Financial Stress

13.0%

Other

3.0%

18

United States Sentencing Commission

Offense and Industry Types

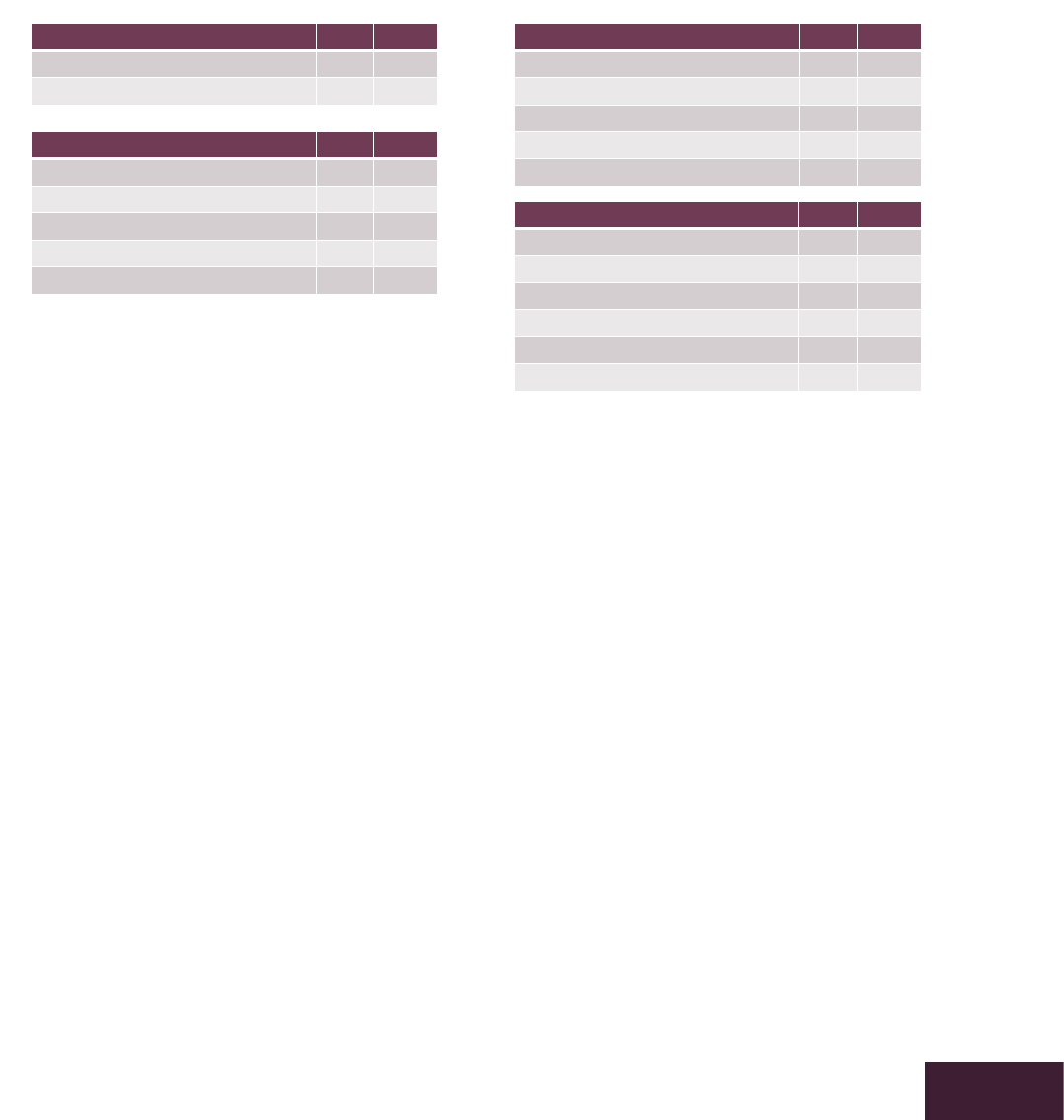

The Commission classies 24

organizational offense types. Six offense

types accounted for 80.4 percent of

all organizational offenders from scal

years 1992 through 2021

(Figure 6). Two

Figure 6. Offense Type of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

30.1%

24.0%

8.4%

6.6%

6.1%

5.2%

3.4%

2.8%

2.6%

2.3%

8.6%

Fraud

Environmental

Antitrust

Food, Drugs, Agricultural

& Consumer Products

Money Laundering

Import and Export

Tax

Bribery/Gratuity/ Extortion

Drugs

Immigration

Other

NOTE: "Other" Offense Type includes: Administration of Justice, Larceny/Theft/Embezzlement, Copyright/Trademark,

Firearms, Racketeering/Extortion, Gambling, Contraband, Obscenity, Civil Rights, Food Stamps, Motor Vehicle,

Archeological Damage, Forgery, and Other Offenses.

of these offense types, fraud (30.1%)

and environmental (24.0%) offenses,

accounted for more than half (54.1%) of all

organizational offenses. Other common

offense types were antitrust (8.4%), food

and drug (6.6%), money laundering (6.1%),

and import and export crimes (5.2%).

19

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

During the 30-year period that the

Commission has collected organizational

sentencing data, it has observed several

notable changes relating to offense type.

For example, during the rst two years

of data collection, few organizational

offenders were sentenced and in these

initial years, antitrust was the most

common offense type observed (Figure 7).

Notably, the Commission included a special

instruction about antitrust organizational

nes in the original guidelines, even before

promulgation of Chapter Eight.

112

The Commission observed a change

in offense types in scal year 1994, when

antitrust was overtaken by fraud as the

most common offense type. From scal

year 1994 through scal year 2010, fraud

continued to be the most common offense

type. That pattern changed in scal year

2005, when the number of environmental

offenses equaled fraud offenses. Since

then, environmental offenses have

replaced fraud as the most common offense

type during several different scal years in

the past decade.

Figure 7. Offense Type of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

5.6%

22.2%

0.0%

25.6%

77.8%

4.4%

Fraud Environmental Antitrust

NOTE: Markers and percentages indicate highest offense type in FY.

20

United States Sentencing Commission

Beginning in scal year 2000, the

Commission began collecting information

on the industry in which organizational

offenders were doing business. Of the

13 industry categories

113

identied by

the Commission, manufacturing (19.6%),

health care services (14.0%), and retail

Figure 8. Industry Type of Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

trade (13.5%) organizations were the

most common industries (Figure 8).

Other common industries included the

transportation (11.9%) and services

(11.1%) industries. These ve industry

categories accounted for 70.1 percent of all

organizational offenders from scal years

2000 through 2021.

19.6%

14.0%

13.5%

11.9%

11.1%

6.7%

6.2%

5.9%

5.1%

6.1%

Manufacturing

Health Care Services

Retail Trade

Transportation

Services

Construction

Finance

Agriculture

Environmental Management

Other

NOTE: "Other" Industry Type includes: Mining, Organizations, Associations, Charities, Public Administration, and

Other Industries.

21

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Although the most common offense

type in the 13 industries varied between

environmental and fraud offenses,

114

certain offense types were more commonly

associated with certain industries

(Figure 9). For example, environmental

offenses were the most common in the

Figure 9. Top Five Offense Types of Organizational Offenders by Industry

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

manufacturing, transportation, agricultural,

environmental management, mining, and

public administration industries. Fraud

offenses were most common in the

health care services, retail trade, services,

construction, and nance industries.

Manufacturing (n=694) 18.1% 24.9% 9.3% 22.0% 2.5%

Health Care Services (n=493) 0.8% 0.8% 1.8% 54.0% 3.3%

Retail Trade (n=478) 3.6% 9.0% 13.6% 17.0% 15.1%

Transportation (n=419) 15.3% 47.7% 5.5% 20.1% 0.7%

Services (n=391) 4.1% 16.1% 4.1% 32.7% 8.7%

Construction (n=237) 4.2% 26.6% 0.4% 39.2% 5.1%

Finance (n=219) 4.1% 11.0% 1.4% 47.0% 18.7%

Agriculture (n=207) 0.5% 54.1% 5.8% 14.0% 1.5%

Enviro Management (n=179) 2.2% 66.5% 0.6% 21.8% 1.1%

Mining (n=73) 1.4% 46.6% 4.1% 21.9% 1.4%

Orgs, Ass'ns, Charities (n=23) 0.0% 8.7% 8.7% 17.4% 21.7%

Public Admin (n=21) 4.8% 57.1% 9.5% 23.8% 0.0%

Other (n=98) 4.1% 19.4% 10.2% 26.5% 14.3%

Fraud

%

Money

Laundering

%

Antitrust

%

Environment

%

Import and

Export

%

These basic metrics may help inform

businesses in certain industry sectors of

areas to prioritize when to "periodically

assess the risk of criminal conduct"

and "take appropriate steps to design,

implement, or modify" its compliance and

ethics program to reduce the risk of the

criminal conduct identied.

115

For example,

as noted above, the data demonstrates

that health care service organizations

were most commonly sentenced for fraud

offenses (54.0%). As such, a company

operating in the health care sector may

wish to tailor its compliance and ethics

program to prioritize fraud prevention in

order to best protect against the types of

issues its employees are most likely to face.

22

United States Sentencing Commission

Individual Co-Defendants and Their

Relationship to the Organizational

Offenders

In scal year 2000, the Commission

began collecting data on cases against

organizational offenders with individual

co-defendants and the individual

co-defendant's relationship to the

organization. Slightly more than half

(53.1%) of the organizational offenders

had at least one co-defendant (Figure

10). The number of co-defendants

uctuated throughout the scal years

as well, with a high of 448 individuals

indicted in scal year 2002 and a low of

135 individuals in scal year 2018. The

number of co-defendants by scal year

was not associated with the number of

organizational offenders; however, the

average number of co-defendants per

organization increased from one co-

defendant in scal year 2000 to two co-

defendants in scal year 2021.

Figure 10. Organizational Offenders Charged With at Least One Individual Co-Defendant

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

No Individual(s)

Charged

46.9%

Individual(s)

Charges

53.1%

23

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

The Commission categorizes the

relationship of individual co-defendants

to the organization into two categories:

high-level authority

116

and not high-level

authority.

117

From scal year 2000 through

scal year 2008, half to a majority of

Figure 11. Percentage of High-Level Authority Individual Co-Defendants

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

individual co-defendants fell within the

category of high-level authority (Figure

11). Starting in scal year 2009, with a

few exceptions,

118

high-level authority

individual co-defendants constituted about

half or fewer individual co-defendants.

72.8%

72.4%

50.2%

62.2%

72.0%

72.9%

67.8%

67.3%

52.0%

37.3%

60.1%

48.1%

34.9%

29.2%

45.1%

50.0%

44.8%

51.6%

57.0%

30.8%

42.7%

25.7%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

24

United States Sentencing Commission

Prior Misconduct

This section reports on all instances

in which an organizational offender

was involved in any prior misconduct.

Presentence reports provide additional

background information about

organizational offenders, even if

the information does not impact the

guideline calculations. For example, an

organizational presentence report details

Figure 12. Organizational Offenders With a History of Misconduct

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

all prior instances of misconduct by the

organization. This includes not only

previous criminal adjudications, but also

civil or administrative adjudications against

the organization. Those instances where

the misconduct impacted the guideline

ne calculation are discussed below. The

majority of organizations sentenced each

scal year did not engage in any prior

misconduct (79.2%) (Figure 12).

No History of

Misconduct

79.2%

History of

Misconduct

20.8%

25

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Compliance and Ethics Programs

Presentence reports for organizational

offenders typically identify whether the

organization had an existing compliance

and ethics program.

119

As discussed in

more detail below, an organization with an

effective compliance and ethics program

receives a culpability score reduction,

thereby lowering its ne range. Since scal

year 1992, the overwhelming majority of

organizational offenders (89.6%) did not

have a compliance and ethics program,

120

and even fewer had a compliance and

Figure 13. Organizational Offenders With a Compliance Program

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

ethics program for which they received

a culpability score reduction. Only 398

organizational offenders (10.4%) had any

compliance and ethics program before

sentencing. The reported presence of a

compliance and ethics program varied each

scal year but remained below 20.0 percent

until scal year 2018 (Figure 13). Fiscal

year 2021 is the only year in which more

than half of the organizational offenders

(58.0%) reported having a compliance and

ethics program.

26

United States Sentencing Commission

CRIMINAL PURPOSE

ORGANIZATIONS

When imposing a ne, the court must

rst determine whether the organizational

offender operated primarily for a criminal

purpose or primarily by criminal means,

121

that is, it had no legitimate business

purpose. Should the court make such a

nding, the guidelines instruct the court

to impose a ne amount (subject to the

statutory maximum) sufcient to divest

Figure 14. Criminal Purpose Organizations

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

the organization of all its net assets.

122

The Commission intended that such a ne

would effectively put the organization

out of business. Commission data reects

that courts infrequently arrive at the

determination that an organization had

no legitimate business purpose. Since

scal year 1992, only 4.0 percent of

organizational offenders have been

identied as operating for a criminal

purpose under the guidelines (Figure 14).

No Criminal

Purpose

96.0%

Criminal Purpose

4.0%

27

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

APPLICATION OF CHAPTER

EIGHT FINE GUIDELINES

Courts are not required to calculate

the Chapter Eight guideline ne range

under two additional circumstances.

First, the ne guidelines in Chapter Eight

exclude certain types of offenses, including

environmental, most food, drug, and

agricultural, and the import and export

offenses.

123

These offenses make up a

signicant percentage of organizational

offenders.

124

In cases where the Chapter

Eight ne guidelines are not applicable,

the court will impose an applicable ne

pursuant to the statutes of conviction.

125

Second, §8C2.2 limits the application of

the ne guidelines if the court ascertains

that the organization (1) cannot and is not

likely to become able to pay restitution, or

(2) cannot and is unlikely to become able to

pay the minimum guideline ne.

126

Under

either prong, a court does not have to

determine the guideline ne range.

127

Since scal year 1992, courts have

applied the ne guidelines in Chapter

Eight of the Guidelines Manual to 2,421

organizational offenders (49.0%). The

application rates ranged from a low of

22.2 percent in scal year 1992, when

the Chapter Eight guidelines rst became

effective, to a high of 69.2 percent in scal

year 1995 (Figure 15). The changes in

these application rates may be related to

the changes in offense types over time

discussed above. In the past ten scal

years (2012–2021), courts applied the

guideline ne provisions to 39.2 percent of

organizational offenders.

Figure 15. Organizational Offenders With Chapter Eight Fine Guidelines Applied

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

28

United States Sentencing Commission

Chapter Eight Culpability Score

The Chapter Eight culpability score

reects the Commission's "carrot and stick"

approach to the organizational sentencing

scheme that bases the ne range, in part,

on the culpability of the organization.

128

The guidelines instruct courts to

determine culpability by considering six

factors. The four aggravating factors,

that is, those "that increase the ultimate

punishment of an organization are:

(i) the involvement in or tolerance of

criminal activity; (ii) the prior history

of the organization; (iii) the violation

of an order; and (iv) the obstruction of

justice."

129

The two mitigating factors

are: "(i) the existence of an effective

compliance and ethics program; and (ii)

self-reporting, cooperation, or acceptance

of responsibility."

130

This section of the

publication provides cumulative data

on the percentage of cases in which

courts either increased or decreased an

organization's culpability score due to the

presence of any of these factors. It then

reports on any trends that the Commission

observed over the 30-year period since

the promulgation of the organizational

guidelines.

Involvement in or Tolerance of

Criminal Activity

The guidelines explicitly require that

an organization promote an organizational

culture that "encourages ethical conduct

and a commitment to compliance with

the law" in order to have an effective

compliance and ethics program.

131

The

antithesis of such an organizational

culture is one in which the organization's

leadership is either actively involved in,

or seemingly indifferent to, the criminal

activity. Thus, the guidelines provide

for an increase in the culpability score

for organizations whose leadership

fails to encourage ethical conduct and

compliance with the law under one of two

circumstances. The score will be increased

if either "an individual within high-level

personnel of the organization

132

[or unit]

133

participated in, condoned, or was willfully

ignorant of the offense" or if "tolerance

of the offense by substantial authority

personnel

134

was pervasive throughout the

organization."

135

This adjustment takes

29

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

into account the size of the organization

by increasing the adjustment from one-

to ve-points, with the higher number of

points added for larger organizations.

136

As reected in Figure 16, more than

half (58.3%) of the organizational offenders

sentenced under the guideline ne

provisions from scal year 1992 through

scal year 2021 received a culpability score

increase for the involvement in or tolerance

of criminal activity. The most common

increase applied for this factor was the

one-point increase for organizations with

at least ten employees and an individual

within the substantial authority personnel

participated in, condoned, or was willfully

ignorant of the offense.

137

Figure 16. Culpability Score Increase for Involvement in or Tolerance of Criminal Activity

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

Tolerance

Adjustment Not

Applied

41.7%

Tolerance

Adjustment

Applied

58.3%

30

United States Sentencing Commission

Prior History

The prior history increase in the

culpability score only applies if the

instant offense occurred within certain

time frames after the prior similar

misconduct.

138

Either one criminal

adjudication for similar misconduct or civil

or administrative adjudications based on

two or more separate instances for similar

misconduct will operate to trigger the

increase.

139

If the offense of conviction

occurred within less than ve years from

the prior history, the prior history receives

a two-point increase.

140

A one-point

increase is awarded if the instant offense

occurred within less than ten years of the

prior history.

141

Organizational offenders infrequently

received a culpability score increase for

having prior history. As shown in Figure

17, courts applied this increase to 54

organizational offenders (2.4%) sentenced

under the ne guidelines since scal

year 1992. When courts did apply this

adjustment, organizational offenders most

commonly received the two-point increase

for a criminal, civil, or administrative

adjudication that occurred less than ve

years prior to the instant offense.

142

Figure 17. Culpability Score Increase for Prior History (§8C2.5(c))

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

Prior History Adjustment

Not Applied

97.6%

Prior History

Adjustment Applied

2.4%

31

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Violation of an Order

An organization's culpability score

increases when the organization's

commission of the instant offense violated

either a judicial order, an injunction, or

a condition of probation.

143

A two-point

increase applies when the organization

either violated a judicial order or injunction

or the organization violated a condition

of probation by engaging in similar

misconduct.

144

The guidelines apply a one-

point increase for any other violations of a

condition of probation.

145

The instances where organizational

offenders received a culpability score

increase for violating a judicial order

were even more infrequent than the

increases for prior history (Figure 18). This

culpability score increase applied to 21

organizational offenders (0.9%) sentenced

under the ne guidelines. Nearly all these

21 organizational offenders received the

two-point increase for violating a judicial

order or injunction or violating a condition

of probation by engaging in similar

misconduct (0.8%), rather than the one-

point increase for a violation of a condition

of probation (0.1%).

146

Figure 18. Culpability Score Increase for Violation of an Order (§8C2.5(d))

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

Violation Adjustment

Not Applied

99.1%

Violation

Adjustment Applied

0.9%

32

United States Sentencing Commission

Obstruction of Justice

An organization receives an increase

in the culpability score when it obstructs

justice or otherwise impedes the

investigation, prosecution, or sentencing

of the instant offense, or failed to

take reasonable steps to prevent the

obstruction, impedance, or attempted

obstruction or impedance.

147

The

guidelines explain that this increase applies

"where the obstruction is committed on

Figure 19. Culpability Score Increase for Obstruction of Justice (§8C2.5(e))

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

behalf of the organization; it does not apply

where an individual or individuals have

attempted to conceal their misconduct

from the organization."

148

The type of

conduct that will trigger this increase is

similar to the conduct that triggers the

Chapter Three adjustment for obstruction

of justice.

149

Courts applied a culpability

score increase for obstruction of justice

to 138 organizational offenders (6.1%)

sentenced under the ne guidelines since

scal year 1992 (Figure 19).

Obstruction Adjustment

Not Applied

93.9%

Obstruction

Adjustment Applied

6.1%

33

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Effective Compliance and Ethics

Program

The existence of an effective

compliance and ethics program is

a mitigating factor that reduces an

organization's culpability score.

150

O O R C S

R E C E P

As discussed in other sections of this report, §8B2.1 describes the minimum

requirements for an effective compliance and ethics program.

152

Since scal year 1992,

11 organizational offenders have received a reduction for having an effective compliance

and ethics program. Aware of public interest in compliance and ethics programs

determined to be effective, the Commission examined the 11 organizational offenders

that received this adjustment in order to provide more robust information about these

offenders than previously available. However, the Commission is not able to provide

details about how these programs complied with the requirements of §8B2.1 since the

presentence reports do not include exhaustive descriptions of the programs.

Most of the organizational offenders that received the compliance and ethics

program reduction were domestic (6)

153

and private organizations (10). The majority

had less than 50 employees (6) and most remained nancially solvent at the time of

sentencing (10).

Among the other culpability score adjustments given, seven organizational offenders

received increases for involvement in or tolerance of criminal activity; all received

a culpability score decrease for acceptance of responsibility with nine of the 11

organizational offenders receiving the two-point reduction for fully cooperating in the

investigation and demonstrating acceptance of responsibility for their criminal conduct.

None of these organizations self-reported the offense to authorities.

Courts rarely apply this culpability score

decrease.

151

Only 11 organizational

offenders (0.5%) have received this

reduction in the past 30 years. These

organizational offenders are discussed in

more detail below.

34

United States Sentencing Commission

Acceptance of Responsibility

Most organizational offenders (85.2%)

to which the guideline ne provisions apply

received a culpability score decrease for

acceptance of responsibility.

154

This is

not surprising since most organizational

offenders plead guilty (92.8%), rather

than proceeding to trial. Most commonly

the organizational offenders (54.6%)

received the two-point reduction for

Figure 20. Culpability Score Decrease for Self-Reporting, Cooperation, and Acceptance of

Responsiblity (§8C2.5(g))

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

fully cooperating in the investigation

and demonstrating acceptance of

responsibility for their criminal conduct

(Figure 20).

155

Few organizational

offenders (1.5%) received the ve-point

reduction for disclosing the offense

to appropriate authorities prior to a

government investigation in addition to

their full cooperation and acceptance of

responsibility.

156

Acceptance

Adjustment Not

Applied

14.8%

Acceptance of

Responsibility

28.9%

Cooperation and Acceptance

of Responsibility

54.6%

Self-Disclosure, Cooperation, and

Acceptance of Responsibility

1.5%

Other

0.2%

35

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

SENTENCING OUTCOMES

The sentences imposed on

organizational offenders typically consisted

of monetary judgments (ne, restitution, or

forfeiture order), and a term of probation.

The conditions of probation may include

a requirement that the organization

implement an effective compliance and

ethics program. This section provides

information on the frequency in which

organizational sentences include each of

these different sanctions.

Monetary Judgments

Since scal year 1992, the courts have

imposed nearly $33 billion in nes on

organizational offenders. Additionally,

courts ordered organizational offenders

to pay restitution and forfeiture amounts

of approximately $6.6 and $6.5 billion,

respectively (Figure 21).

Since scal year 1992, courts

determined that approximately two-thirds

(65.6%) of organizational offenders were

able to pay a ne (Figure 22). The ability

Figure 21. Total Fine, Restitution, and Forfeiture Amounts

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

$32,763,701,169

$6,638,615,691

$6,469,447,892

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

$35

Total Fine Amount Total Restitution Amount Total Forfeiture Amount

in billions

36

United States Sentencing Commission

to pay is an initial step in the application

of the Chapter Eight ne guidelines.

Likewise, when a court determines that an

organizational offender cannot pay a ne,

the court need not compute the guideline

ne range.

157

Figure 22. Organizational Offenders With

Ability to Pay Fine

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

Courts imposed a ne on 3,625

organizational offenders (73.3%) (Figure

23). In nearly every scal year, courts

imposed nes on more than two-thirds

of the organizational offenders.

158

Since

scal year 1992, the overall average ne

amount imposed was over $9 million and

Unble to Pay Entire

Fine Imposed

34.4%

Able to Pay Entire

Fine Imposed

65.6%

Figure 23. Imposition of Fine Ordered on

Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

No Fine Imposed

26.7%

Fine Imposed

73.3%

37

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

the median amount was $100,000. As

reected in Figure 24, the average and

median ne amounts differed by scal

year.

159

In the aggregate, the ne amounts

varied over time. In the early 1990s,

the average ne amount was less than

Figure 24. Fine Amount Ordered to be Paid by Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

$500,000, it generally increased over

time, and peaked in scal year 2017 at $67

million. There was less variation when

measuring the median ne amount, which

ranged from approximately $29,550 to

$662,500 over the study period.

$0

$100,000

$200,000

$300,000

$400,000

$500,000

$600,000

$700,000

$0

$10,000,000

$20,000,000

$30,000,000

$40,000,000

$50,000,000

$60,000,000

$70,000,000

$80,000,000

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Avera ge Median

38

United States Sentencing Commission

Courts ordered restitution as part of a

sentence less frequently than nes (30.9%

and 73.3%, respectively) (Figure 25). For

the organizational offenders ordered to pay

restitution, the average restitution amount

imposed was $4.4 million and the median

restitution amount imposed was $180,486.

The average and median restitution

amounts also varied from scal year 1993

to scal year 2021 (Figure 26).

160

In the

1990s, the average restitution amount

was less than $1 million each scal year.

Since the turn of the century, the average

restitution amount has varied from a low

of $447,440 in scal year 2012, to a high of

over $17 million in scal year 2010.

Figure 25. Imposition of Restitution Ordered

on Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

No Restitution

Imposed

69.1%

Restitution

Imposed

30.9%

$0

$100,000

$200,000

$300,000

$400,000

$500,000

$600,000

$700,000

$800,000

$900,000

$1,000,000

$0

$5,000,000

$10,000,000

$15,000,000

$20,000,000

$25,000,000

$30,000,000

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Average Median

Figure 26. Restitution Amount Ordered to be Paid by Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

39

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Courts entered comparatively fewer

forfeiture orders against organizational

offenders (10.4%). The percentage of

forfeiture orders entered each scal year

ranged from none in scal year 1992 to

Figure 27. Imposition of Forfeiture Order on Organizational Offenders

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

24.2 percent in scal year 2016 (Figure 27).

Notably, entry of forfeiture orders against

organizational offenders has increased

from scal year 1992 to scal year 2021.

40

United States Sentencing Commission

Probation

"Section 8D1.1 sets forth the

circumstances under which a sentence

to a term of probation is required."

161

Courts sentenced over two-thirds of

organizational offenders (69.1%) to a term

of probation (Figure 28). The rates of

imposition of probation are not unexpected

given the broad circumstances under which

the guidelines require imposition of a term

of probation. Courts shall order a term of

probation under specied circumstances,

including if such a sentence is necessary to

"secure payment of restitution," "enforce a

remedial order," or "ensure completion of

community service,"

162

if the organization is

sentenced to pay a monetary penalty that is

not paid in full at the time of sentencing,

163

or if the organization has 50 or more

employees or is otherwise required by

law to have an effective compliance and

ethics program and does not have such a

program.

164

The maximum term of probation that

courts may impose is ve years.

165

The

average length of the terms of probation

imposed on organizational offenders was

39 months and the median length was 36

months.

Figure 28. Organizational Offenders Sentenced to Probation

Fiscal Years 1992–2021

No Probation

Ordered

30.9%

Probation

Ordered

69.1%

41

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

Implementation of an Effective

Compliance and Ethics Program

As a condition of probation, the

court can order that the organizational

offender take additional actions it

deems appropriate,

166

including the

implementation of an effective compliance

and ethics program.

167

Since scal year

2000, courts ordered approximately 20

percent (19.5%) of organizational offenders

to implement an effective compliance

and ethics program (Figure 29).

168

The

percentage of organizations ordered to

implement an effective compliance and

ethics program each scal year was rarely

more than one-third of the organizational

offenders and ranged from 5.1 percent in

scal year 2009 to 35.5 percent in scal

year 2012 (Figure 30).

Figure 29. Organizational Offenders Ordered

to Implement Compliance Program

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

Figure 30. Organizational Offenders Ordered to Implement Compliance Program

Fiscal Years 2000–2021

No Compliance

Program Ordered

80.5%

Compliance

Program Ordered

19.5%

14.0%

16.8%

15.1%

12.0%

16.2%

18.8%

19.8%

24.1%

6.2%

5.1%

28.2%

19.4%

35.5%

23.8%

27.8%

28.2%

20.5%

22.1%

25.3%

18.6%

29.8%

16.7%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

42

United States Sentencing Commission

CHAPTER THREE

I

O S

G

As mentioned above, the impact of the

organizational guidelines is not limited to

their application in criminal sentencings.

Incentivizing organizations to develop and

maintain internal programs to prevent,

detect, and report criminal conduct is one

of the major innovations of the Chapter

Eight organizational guidelines,

169

so their

inuence has been evidenced in other

areas.

Not only did the organizational

guidelines inuence the prosecutorial

policy of the DOJ, they also inuenced the

policies of other regulatory agencies.

170

Additionally, the organizational guidelines

were "credited with helping to create an

entirely new job description: the Ethics and

Compliance Ofcer."

171

Public Sector Response to the

Guidelines

The organizational guidelines inuence

the decisions of federal agencies in

bringing enforcement actions against

organizations. The guideline criteria for an

effective compliance and ethics program

also serve as a model for compliance and

ethics program guidelines created by other

federal agencies.

U.S. Department of Justice

In 1999, the DOJ announced that

the existence and adequacy of an

organization's compliance program and

efforts to implement or improve an existing

compliance program were among the

factors that prosecutors would weigh

when determining whether to prosecute

an organization. The DOJ made the

announcement through a memorandum

issued by then-Deputy Attorney General,

Eric H. Holder, regarding bringing criminal

charges against corporations.

172

The

DOJ later codied these factors in the

Justice Manual.

173

When evaluating the

effectiveness of corporate compliance

programs, the DOJ expressly relies upon

the criteria set forth in §8B2.1.

174

While

the existence of a compliance program will

not absolve the organization of its criminal

liability, it may result in the DOJ choosing

to defer prosecution or use other means

to elicit the organization's cooperation to

change its business practices.

175

Within the last decade, the DOJ has

issued written guidance meant to assist

prosecutors in making informed decisions

about the effectiveness of a compliance

program.

176

In November 2012, the DOJ

Incentivizing organizations to

develop and maintain internal

programs to prevent, detect,

and report criminal conduct is

one of the major innovations of

the Chapter Eight organizational

guidelines, so their influence has

been evidenced in other areas.

43

The Organizational Sentencing Guidelines: Thirty Years of Innovation and Inuence

and the SEC jointly issued a resource guide

aimed, in part, at providing businesses

and individuals with information to help

them implement effective compliance

programs.

177

The resource guide

incorporates the elements of an effective

compliance program, as set forth in §8B2.1,

to provide insight into the aspects of

compliance programs that the DOJ and

SEC assess.

178

The DOJ has since provided updated

guidance on the Evaluation of Corporate

Compliance Programs, which provides

greater clarity on some key issues

prosecutors consider when assessing

the adequacy of corporate compliance

programs during charging and settlement

decisions.

179

The guidance, which was rst

developed in 2017 under the leadership

of the DOJ's rst "corporate compliance

expert"

180

and was updated in 2019 and

2020, lays out the "fundamental questions"

that prosecutors should ask about

compliance programs:

• Is the corporation's compliance

program well designed?

• Is the program being applied

earnestly and in good faith? In

other words, is the program being

implemented effectively?

• Does the corporation's compliance

program work in practice?

181

The guidance then describes in detail

the topics that prosecutors should consider

when answering those questions.

182

The

elements of an effective compliance

and ethics program, set forth in §8B2.1,

underlie these topics.

183

Under the current administration, the

DOJ has "prioritized building a wealth

of compliance expertise among [its]

prosecutors and dedicating resources