Community Supported Agriculture

Agricultural

Markeng

Service

April 2017

New Models for Changing Markets

ii

Recommended Citaon: Timothy Woods, Mahew Ernst, and Debra Tropp. Community Supported Agriculture – New

Models for Changing Markets. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Markeng Service, April 2017. Web.

Acknowledgments: This work was funded by Cooperave agreement 12-25-A-5660 with the Agricultural Markeng

Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This study necessarily involved extensive interviews with numerous

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) operators and builds on the previous case study of selected CSAs published as

The Changing CSA Strategic Business Model. The authors would like to again acknowledge the contribuons of many to

that study that were used to frame the quesons for this survey. James Barham with AMS provided regular guidance on

the survey design and cases.

Disclaimer: The opinions and conclusion expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of

Agriculture or the Agricultural Markeng Service.

Author Contact:

Timothy Woods, m.woods@uky.edu, 859-257-7270

USDA Contact:

Debra Tropp, Debra.T[email protected], 202-720-8326

In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulaons and policies,

the USDA, its Agencies, oces, and employees, and instuons parcipang in or administering USDA programs are

prohibited from discriminang based on race, color, naonal origin, religion, sex, gender identy (including gender

expression), sexual orientaon, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public

assistance program, polical beliefs, or reprisal or retaliaon for prior civil rights acvity, in any program or acvity

conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint ling deadlines vary by pro-

gram or incident.

Persons with disabilies who require alternave means of communicaon for program informaon (e.g., Braille, large

print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202)

720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Addionally, program

informaon may be made available in languages other than English.

To le a program discriminaon complaint, complete the USDA Program Discriminaon Complaint Form, AD-3027, found

online at How to File a Program Discriminaon Complaint and at any USDA oce or write a leer addressed to USDA and

provide in the leer all of the informaon requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-

9992. Submit your completed form or leer to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Oce of the Assistant

Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3)

email: program.intak[email protected].

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.

iii

Community Supported Agriculture

New Models for Changing Markets

Timothy Woods and Mahew Ernst, University of Kentucky

Debra Tropp, USDA Agricultural Markeng Service

iv

v

Contents

Introducon 1

Background and Methods 2

What is the issue? 2

What did the study nd? 3

How was the study conducted? 4

Changes in the CSA Model Over Time 6

CSA Growth Opportunies 7

CSA Business Models and Risk Management 8

Future of Community Supported Agriculture 9

CSA Manager Survey Design and Data 10

CSA Business Characteriscs 11

Other Market Channels for CSAs 14

Changes in CSA Products, Business Funcons, and Protability 15

Evaluang Local Food Market Demand, Compeon, and Shareholder Recruitment 19

Cooperaon Potenal for Mul-Farm CSAs 22

Discussion and Conclusions From the CSA Manager Survey 24

The Changing CSA Business Model – Six Case Studies 25

CSA Interview Queson Themes 25

CSA Case Study 1: Elmwood Stock Farm 27

CSA Market Discovery 28

For Experienced Growers 28

Season Extension 29

Shareholders 29

Communicaon and Customer Connecon to Farm 30

Regional Eorts, Mul-Farm CSAs and What is a CSA? 31

Growth Opportunies 31

CSA Case Study 2: Penn’s Corner Farmer Alliance 32

CSA Market Discovery 33

Relying on Experienced Growers 34

Quality Essenal 34

vi

Season Extension and Value-Added Processing 35

CSA Growth Opportunies 36

Advantages of Being a CSA and How the Business Model is Shiing 37

Sidebar: CSAs and E-Commerce 37

CSA Case Study 3: Farmer Dave’s 38

Farmer Dave’s Sliding-Scale CSA Business Model 38

Reaching Low-Income CSA Shareholders With Urban Partners 39

CSA Case Study 4: FairShare CSA Coalion 43

Madison Eaters Revoluonary Front – The Beginning 43

Cash Flow by Cookbook 43

Community Connecons 44

Health Rebate Program Keys 45

Outlook and Producer Perspecve on Health Rebate Program 45

Other Funcons of FairShare 46

Future of FairShare CSAs 47

CSA Case Study 5: Innovaons in Denver Urban and Urban Fringe Markets 48

CSAs and Urban Agriculture 48

Granata Farms, Downtown Denver, Elaine Granata 48

Star Acre Farms, Arvada, CO

CSAs and Planned Urban Development Iniaves, Jackie Raehl 49

Issues for Denver Metro CSAs 50

Partnerships Viewed Essenal to Growth 50

Peer-to-Peer Learning: Building Farmers Programs 51

Changes in CSAs over Time 51

Relaon to Other Market Channels 51

Perspecves on the Future of Denver-Area CSAs 52

CSA Case Study 6: Fair Shares Combined CSA 53

An Innovave Local Food Retailer 53

Building Suppliers and Shareholders 53

Changes in Customers, Business 54

Producer Perspecves 55

Tips and Consideraons for Enhancing CSA Success

Through Strategic Business Pracces 56

References 58

Photo Credits 60

1

A

steady growth in CSAs and related markeng

structures has been observed concurrent with

the growth in direct markeng and consumer interest in

local foods. The CSA model has evolved from its original

emphasis on organic and sustainable agriculture along

with various measures of shareholder risk-sharing with

producers (Ernst and Woods, 2009). Current business

models for CSAs are diverse and innovave. Producers

have adapted the CSA model to t a variety of emerging

direct markeng opportunies, including:

• Instuonal health and wellness programs;

• Mul-farm systems to increase scale and scope;

• Season extension technologies; and

• Incorporang value-added products, oering

exible shares, and exible electronic purchasing

and other e-commerce markeng tools.

A 2009 regional survey by Woods et al., revealed that

CSA producers tend to have a diversity of market outlets

and have used the CSA model to both scale up and to

build a farm brand in community markets. Most CSAs,

connuing with the current survey, are small (with some

notable excepons) but growing, maintaining fewer than

80 shareholders. Most businesses have been started

within the past 5 years. Producers have been able to

diversify markeng channels readily from a CSA base to

include direct to restaurants and small grocers and even

work with wholesale distributors to reach a wider market

area. However, the role and dynamics the CSA plays in

helping producers to supply food compevely in the local

food system is not very well understood as it is a relavely

new business structure with a rapidly evolving model of

operaon.

Introduction

This study proposed to idenfy the trends in CSA business

model adaptaon including changes in product innovaon

and protability drivers as the CSA markeng model

evolves to address emerging consumer preferences and

direct markeng opportunies. By conducng a naonal

survey of CSAs, researchers hoped to:

1. Describe the current use of the CSA business model,

including scale and regional dierences;

2. Idenfy the role and strategic dynamics of the CSA

model in a local foods business start-up;

3. Idenfy the emerging and adapted uses of the CSA

model to pursue scale individually and through

cooperaon and pursue alternave local foods

markets; and

4. Examine perspecves of CSA operators on expected

future business and market innovaons.

These objecves will yield important new knowledge

regarding the trends and trajectory of CSAs, providing

perspecves on changes in the CSA business model for

consideraon by current and prospecve managers, and

idenfying future research and educaon program needs

for CSAs for supporng agencies such as Extension, USDA,

and local food Nongovernmental Organizaons.

Many of the themes and issues featured in the naonal

survey were informed by a series of focus group interviews

conducted with CSA operators in six geographically diverse

parts of the country. The results of these focus group

interviews appear in summary format in the laer part of

this report.

2

Background and Methods

What is the issue?

This project provides an analysis of the emerging

markeng and business strategy trends of CSAs

1

in the

United States. Regional studies (Strochlic and Shelly,

2004; Oberholtzer, 2004; Woods et al, 2009; Galt et al,

2012) have shed some light on trends with this business

model, but have tended toward a narrower geographic

analysis, have emphasized sociological elements, or had

not explored CSAs as part of a comprehensive markeng

strategy. These are important dimensions to CSAs given

their historical roots, but their role as part of a producer’s

local foods/direct markeng strategy is changing and

not well understood. Regional and scale dierences

are evident. Naonal studies, such as the Census of

Agriculture, indicate 12,617 farms marketed through a CSA

in the 2012 Census, up slightly from the 12,549 idened

in 2007. Geng an accurate count on CSA businesses is

more dicult than it may seem, given the expansion of

mul-farm, food-hub, and non-farm-based CSA delivery

models. The divergence in CSA counts across various

public and private agencies has been addressed by Ryan

Galt (Galt, 2011) and the measurement problem connues.

The Biodynamics Associaon, one of a number of local

food system advocacy groups, in an eort to provide a

history of CSA, cites McFadden’s 2012 esmate of between

6,000 and 6,500 CSAs, but also references LocalHarvest

esmates at that me of 4,571 acve CSAs

2

(Biodynamic

Farming and Gardening, 2012). The CSA denion and

counng has only become more dicult. The variaons

of the CSA value proposion and markeng strategy for

producers are also not well understood. Some producers

have used the tradional CSA model as a market entry

point for local foods distribuon and then graduated to

other business models as scale allowed. Others have

adapted the tradional CSA model to CSA-like models that

beer accommodate single or mul-farm scale economies.

This study ulizes a naonal survey of CSA managers

conducted in 2014 to document changes in the CSA model

with parcular aenon paid to regional dierences,

urban/rural locaon of the farm, and the age of the CSA.

Given the rapid growth and increased diversity of business

pracces being observed, USDA/AMS, in partnership with

the University of Kentucky, conducted the naonal survey

of CSA managers. The survey’s aims were to document the

emerging markeng and business strategies of producers

using the CSA model and to understand the variaons in

performance and sustainability of the business model.

Part of the analysis provides a current descripon of

the CSAs across the country, but a further objecve is to

understand the dynamics of this model in the context of

entry into the local foods market, including understanding

the CSA manager percepons of compeng local foods

delivery models in various market contexts. The study

documents manager interest in mul-farm collaboraons

to pursue various innovaons and adaptaons of the

tradional CSA model. The results should be instrucve

to CSA operators, policy makers, and support agencies

working alongside various local foods eorts.

The CSA business model has evolved signicantly

as entrepreneurs and market forces have opened

opportunies for the implementaon of the model

in ways quite unlike the early CSA operaons. New

products, season extensions, mul-farm collaboraons,

new shareholder groups, markeng collaboraons with

dierent organizaons, innovave aggregaon and

delivery strategies, new urban producon connecons,

and health and wellness alliances are among the current

trends reshaping the CSA business. Neil Stauer, General

Manager for Penn’s Corner Farm Alliance in Pisburgh, PA,

noted that CSAs have changed from an emphasis on the

farmer to the consumer. “When CSAs were rst around,

it seems like it was more like customers saying, ‘We really

believe in you, the farmer, and how can we make this work

for you?’” he observed. “Now, it seems like it has shied

and the farmers are saying, ‘How can we make the CSA

work beer for you, the customer?’”

A series of six case studies were completed based on

interviews with farmers, managers, and customers who

represented various models of CSA business organizaon,

market focus, producon and markeng innovaon across

the country. While the authors recognize that there are

numerous cases of innovaon across CSAs naonally – and

1 Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), as used in this report, is dened as a producer-consumer local producon and markeng partnership

that involves a subscripon-based contract for the delivery of seasonal products from the farm. The tradional CSA placed substanal emphasis

on sustainable agriculture, shared producon risk, consumer involvement with producon acvies, and authencity of local sourcing (Bougherara,

Grolleau, & Mzoughi, 2009; Henderson & Van En, 1999). A “shareholder” is dened here as a CSA subscriber, typically a consuming household and

a “share” is the season subscripon.

2 Localharvest is a web directory for local sourced foods through a variety of market channels. Their naonal acve CSA count for April 2015 was

5,638 according to www.localharvest.org

3

these aren’t exhausve—they believe that these stories

add texture and nuance to the changing character of CSAs

in the United States, and help reveal how they are adapng

to new opportunies, but also to new compeon. Cases

were selected for geographic diversity as well as types

of innovaon, including CSAs from Kentucky, Wisconsin,

Pennsylvania, Missouri, Massachuses, and Colorado.

A geographically diverse case-based approach can be

parcularly useful for gaining producer and agency

perspecves on innovaons in the CSA markeng model.

To that end, a set of CSAs were selected naonally that

represented tradional single farm models; co-operaves/

mul-farm CSAs; low-income consumer-targeted CSAs;

mul-farm innovaons targeng parcular consumer

segments with a unique health and wellness markeng

partner; CSAs associated with urban market innovaons;

and a for-prot food hub concept that ulized a CSA

aggregaon and distribuon model. Interviews with key

informants aliated with each CSA or CSA community

were coordinated through a variety of agency contacts.

What did the study find?

The study documents important trends associated with

the CSA business model naonally. The CSA model has

been in place for many farms for some me now. The

earliest CSAs established in the United States date back to

the mid-1980s, and more than 25 percent of the managers

who responded to the survey indicated their CSA had

been in operaon for over 10 years. CSAs have grown in

number as documented in the Census of Agriculture, but

the naonal CSA manager survey indicates they have also

grown in shareholder size over the past 3 years (note

table 4).

The CSA business model has denitely evolved. Only about

27 percent of the CSAs surveyed are cered organic, a

departure from the focus of the earlier CSA movement (46

percent were cered organic and 92 percent were at least

using organic or biodynamic pracces in the 2001 survey

by Lass et al). Many of the surveyed CSAs have taken

advantage of new direct markeng tools, including web-

based sales, season extension technologies, and oering a

greater diversity of products – including processed items.

Most of them have a diversied markeng mix, ulizing

a variety of other market channels. The majority of CSA

managers who responded to our survey also sell through

farmers markets and area restaurants, but oen include

other market channels, as well.

Surveyed CSA managers generally view their markets

posively for growth potenal and see the CSA distribuon

model as an important contributor to farm sales (58

percent indicate that the CSA accounts for at least half of

all their farm sales) and protability. About 55 percent

indicated that the protability of their CSAs had at least

increased to some degree since they had started their

CSA – with 10 percent indicang that their protability

had “increased a lot.” Furthermore, more than half of

surveyed managers expected their CSA sales to increase

over the next 2 years.

There is some evidence of variability in perceived market

demand and the protability/performance outlook for

CSAs depending on region, proximity to urban centers,

and the CSA’s age, which are documented and discussed

throughout the study. The CSA distribuon model is

being adapted to numerous products, markets, and

groups of producers. This study found roughly similar

ulizaon of various and alternave market channels

for CSAs regardless of their proximity to urban locaons.

The dierences were more evident in the producon

techniques, product markets, and business strategies

implemented, highlighng the diversity of approaches

CSA operators adopted depending on their specic

market context.

CSAs use websites to sell product and give informaon

on locaons of farm stands, restaurants and wholesale

markets where their product is sold.

4

The study documents dierences in manager percepons

of compeon for local food to local markets coming from

new CSAs, expansion from exisng CSAs, farm markets,

and other retail channels that have also expanded local

foods markeng. The determinaon of who is the

compeon seems to be largely inuenced by proximity

to urban markets and the age of the CSA, and to some

degree, on the CSA’s locaon.

Surveyed CSA managers also seemed generally

interested in exploring mul-farm business innovaons

and collaboraons that enable them to pursue new

markets, engage in more aggressive promoon, oer

vouchers to select consumer targets, share logiscs,

and share producon. However, the degree to which

these innovaons had been successfully adopted by CSA

managers varied considerably. For example, the interest

in voucher programs targeng low-income consumers and

clients of health and wellness programs seemed to greatly

outweigh current pracce, suggesng that there seems to

be room to help facilitate selected aspects of mul-farm

CSA cooperaon before it reaches its full market potenal.

The case studies provided numerous illustraons of

business model innovaon, underscoring the fact that the

CSA markeng model connues to be adapted to t many

market circumstances. Based on manager percepons

of business growth, compeveness, and protability,

there appears to be growth potenal for a diversity of

successful strategies within the CSA framework – including

single farm, mul-farm, co-operavely owned, and even

non-farm owned. The study also idened a diversity of

market targets as yet untapped, including the tradional

shareholder who prefers organic produce. However, it is

clear from both our case studies and our survey that CSA

managers are increasingly focused on using their CSA as a

way to facilitate consumer access to local foods in general,

rather than specically targeng consumers of organic fruit

and vegetables. Farms and farm networks are connually

nding new ways to reach non-tradional market

segments with CSA shares. This includes incorporang

e-commerce, adding products through season extension

and mulple season oerings, adding shares for alternave

product lines beyond tradional produce, and working

with urban, health/wellness, and community development

partners to access a broader base of customers, including

lower income shareholders. The Madison, WI, FairShare

CSA Coalion has ulized wellness plan vouchers to

substanally expand demand for share parcipaon with

local farmers. Coalion members, as sll independent

farm-CSAs, have organized to both collecvely promote

the voucher program and to provide quality standards

crical to maintaining the program. Denver area CSAs

have provided many of their own innovaons including

collaboraons with city planning, urban markets, and

peer-learning among CSA farmers. Non-farm aggregaon

models to deliver CSAs have been emerging as well,

including the Fair Share CCSA in St. Louis where a small

food retailer built a CSA business around a shared vision

for local foods with area farmers.

How was the study conducted?

This study is a follow-on study that explored six cases in

CSA innovaon. The earlier study included both individual

farm and mul-farm iniaves and explored a variety of

non-tradional approaches to CSA products and target

markets. The study ulized a web-based survey to explore

naonal business development trends for CSAs based

on observaons in the inial case studies. We designed

the survey instrument to examine current business

characteriscs, sales in related market channels, changes

in producon and markeng strategies, compeon and

local food demand, prospects for business cooperaon,

and shareholder recruitment. The target populaon was

CSAs that had been in operaon for at least 2 years, given

the emphasis on changes in business acvies.

3 The directory is based at the Robyn Van En Center at Wilson College at www.wilson.edu.

CSAs innovate to reach urban and non-tradional

markets in East Boston.

5

There was no current naonal CSA database of addresses

available from which to develop a distribuon list.

Therefore, a master list had to be compiled drawing from

communicaons from State departments of agriculture,

local foods registers, and food markeng databases.

Many of these were out of date and required updang

for current contacts. A database was assembled through

a variety of earlier business lists assembled by the Robyn

Van En Center,

3

but expanded through updates provided

by various State departments of agriculture, grower

associaons, and LocalHarvest.com lisngs. We assembled

a database and sampling process that would provide equal

representaon in the nal sample and allow comparison

of regional dierences. A balanced sample of 525 was

therefore selected from each of the four regions of the

country, using USDA designaons for Southeast, Northeast,

North Central, and West.

We sent a preliminary invitaon to the CSA manager or

lead operator requesng parcipaon and explaining the

goals of the survey. Any CSA could opt out. We followed

up 3 weeks later with a second invitaon. Surveys were

distributed to 2,100 addresses that did not opt out of the

study, 525 to each region. A total of 495 CSAs returned

usable surveys during the period of February to July 2014,

yielding an approximate 24 percent eecve return rate.

Usable responses regionally were collected from the

Northeast (100), North Central (119), Southeast (87), and

West (189), providing some dierences in response rates

by region.

We used a case-based approach to gaining producer and

agency perspecves on innovaons in the CSA markeng

model ahead of the naonal CSA manager survey. A set of

CSAs were selected naonally that represented:

• Tradional single farm models,

• Cooperaves/mul-farm CSAs,

• Low-income consumer-targeted CSAs,

• Mul-farm innovaons targeng unique consumer

segments with a health and wellness markeng

partner,

• CSAs associated with urban market innovaons,

and

• A for-prot food hub concept that ulized a CSA

aggregaon and distribuon model.

These cases were selected to provide a diversity of market

and geographic perspecves. We coordinated Interviews

with key informants aliated with each CSA or CSA

community through a variety of agency contacts, including

local Extension oces, producer associaons, local food

non-prots, and local government agencies.

6

Changes in the CSA Model Over Time

F

armers who have adapted and innovated to reach

growing local market demand have found numerous

ways to adapt the CSA subscripon model in a way that

ts their goals and unique market condions. The model

is highly exible to accommodate a variety of products

– produce, meat, dairy, eggs, as well as value-added and

processed products coming from the farm.

The denion of CSA has evolved as well. Farmers and

shareholders both have adapted the concept to encompass

and represent a variety of local food systems relaonships.

The more successful models, those CSAs characterized

as sustainable business ventures while meeng the

mutual mission goals of the farm and shareholders, have

maintained a close farmer-consumer connecon. The

inclusion of urban community development and health

care workers has actually added an interesng new

dimension to the CSA community, as well as peer-to-peer

learning. Many consumers view the CSA as an extension of

the community farm market experience and seem happy

to include other community partners.

The term “CSA” is becoming increasingly confusing to

many. Most farmers and consumers recognize and

understand the subscripon model, but need addional

reecon around the meaning of community as it relates

to sustainability. As other business models emerge that

are seeking to take advantage of the growing demand

for local food, farmers will need to pay parcularly close

aenon to the meaning of community as a means of

dierenang themselves to their core consumers.

Most of the farmers we interviewed selling through CSA

also had signicant markeng acvity in community

farm markets, on-farm retail, direct to restaurants and

grocers, and other market channels. Farmers were

selling increasingly more through the CSA as the model

was able to be adapted to their customer needs. Few

farmers recommended the CSA as a starng point for new

producers. The producon management, distribuon,

and markeng require considerable experse and benets

substanally from experience.

7

CSA Growth Opportunities

G

rowth opportunies fall in a number of categories

– new products, season extension or year-round

sales, scaling up through mul-farm partnerships, ulizing

e-commerce, and connecng to new consumer segments.

This can include low-income consumers or health and

wellness programs.

New product opportunies have emerged for CSA

distribuon of all dierent kinds of products – cheese,

sh, owers, wine, sauces, and other custom-processed or

co-packed products have added to consumer interest and

seem to relate to shareholder retenon. Shareholders are

drawn to greater variety, but farms must be cauous not to

press for too great a variety. There are diminishing returns

associated with greater inventory management.

Season extension is a great opportunity, allowing farms

to signicantly expand the scope, ming, and quality of

products coming from protected agriculture environments.

This makes part-season shares and specialty shares more

feasible as well.

The role and eecveness of mul-farm CSAs was mixed.

There is a sacrice in control and challenges with managing

quality and consistency. There is a risk of loss in perceived

value to the shareholder moving from a farm estate

product to an aggregated “local” product that may not

be idened with a specic farm. Sll, many producer

associaons that are aggregang product through

warehouses (e.g., Penn’s Corner) have found equitable

ways to ulize their collecve scale to put in place

resources like managers and/or collecvely promote their

products to the local foods community. Others, somewhat

aligned with the food hub model, have found volume and

product variety advantages to aggregaon, creang market

opportunies for parcipang farmers who probably

wouldn’t be there otherwise (e.g. Fair Shares in St. Louis).

E-commerce will likely play an increasingly important role

in both logiscs and markeng for CSAs. New rms like

Farmigo and Small Farm Central are among a number of

new private support ventures that help CSAs expand this

means of shareholder and producer communicaon and

trade. Social media connects closely with the community

dimension of CSA and can also play a part in enhancing

producer-shareholder linkages.

8

CSA Business Models and

Risk Management

M

any advantages to the CSA model were noted

throughout the various interviews. Farmers in

the more tradional single model connue to idenfy

cash ow, relave protability to other markeng

channels, producon planning, and product exibility as

main aracons. Farmers noted that, much like farmers

markets, the CSAs can be a good plaorm to introduce

new products on an experimental basis or to expand

variaons on share types (adding meat or egg shares,

or oering half-shares), taking advantage of a highly

interacve direct-to-consumer framework that can provide

good feedback on demand.

However, mul-farm models can be benecial as well.

Mul-farm CSAs have the potenal to help farmers

manage specialty crop risk by contribung to a more

diverse porolio of products that can collecvely be

more aracve to local food buyers. They can open new

markets through expanded scale or scope. Developing this

advantage requires having the right partners and not every

CSA is willing to engage other producers where supply and

quality may not be consistent.

CSAs have also successfully worked through community

partnerships with urban, land, or economic development

agencies that help farmers access non-tradional markets.

These partnerships make the CSA model aracve largely

because products and services can be readily adapted to

customer needs in markets not tradionally served by

these farms. The CSA business model, whether single or

mul-farm, has been adapted to allow farmers to make a

stronger connecon to their most loyal customers using

more exible products and services and cost-eecve

distribuon models.

Farmers do many things to collaborate to make their CSA

successful including coming together to market, sharing

personnel resources, diversifying products, adding new

product lines, developing shared e-commerce plaorms,

and providing greater supply assurance to shareholders

and/or wholesale customers. Farmers also develop peer

educaon and shareholder educaon on health and

nutrion through collaboraons with other community-

based partners.

CSAs diversify their products

through meat and egg shares.

9

Future of Community

Supported Agriculture

M

ost farmers in these cases remained very opmisc

about the opportunies for growth and connued

innovaon. The CSA seems to be both exible and

eecve as a means for connecng with consumers who

value local products and closer relaonships with farms.

The future of CSAs will have to balance the economic

benets of various mul-farm and third-party aggregaon

strategies that necessarily place increased distance

between the farm and the consumer and the challenges

and growth limits of remaining very focused on a local

community.

There is increasing compeon for the local food dollar as

consumer demand for local food expands. Other retailers

see a range of preferences for local products – from a

core group with very strong preferences and concepons

for local to those who might have some interest in local

but may be more price-sensive. Grocers, specialty

wholesalers, and other dedicated distribuon rms have

tried to make inroads into these markets and provide some

degree of new compeon with CSAs.

Farms that are able to clearly dierenate their oerings

through close or direct relaonships with customers are in

a good posion to maintain their advantage, parcularly

with the core consumer. There are strategic quesons

farmers must address as they consider mul-farm models

and the future of CSA, parcularly as individual farm

identy is lost. These types of aggregaon models place

them closer in concept to the retailers that are pursuing

the loyal local foods customer.

The inclusion of new community partners that may not

have been previously associated with CSA oers substanal

promise for CSA farms to build on their value proposion.

This includes collaboraons with health and community

agencies, economic development partners, low-income

support agencies, urban development projects, community

property development projects, and other local food

markeng partners, all of which can contribute to new

opportunies for CSA farms.

The balance between building toward a crical mass of

local food awareness distributed through a variety of local

channels and actual market compeon will be a factor

CSAs will have to watch closely. They will need to pay

aenon to their unique value proposion and how the

CSA can uniquely deliver that – parcularly to the core

local foods consumer who places very high value on a

close relaonship with the farmer. The strategic reach of

retailers and other aggregators is generally more mediated

as they try to reach local consumers, but they are geng

beer at it. Figure 1 suggests a conceptual framework

for considering the spectrum to local food marketers and

their strategic reach against the local food consumer value

proposion.

Figure 1. Local Food Strategic Reach and Value Proposion to CSA Shareholders

10

CSA Manager Survey Design and Data

W

e ulized a web-based survey to explore naonal

business development trends for CSAs. The survey

instrument was designed to examine current business

characteriscs, sales in related market channels, changes

in producon and markeng strategies, compeon and

local food demand, prospects for business cooperaon,

and shareholder recruitment. CSAs that had been in

operaon for at least 2 years were the target populaon,

given the emphasis on changes in business acvies.

There was no current naonal CSA database of

addresses, so we compiled a master list drawing from

communicaons from State departments of agriculture,

local foods registers, and food markeng databases. Many

of these were out of date and required updang. We

selected a sample of 525 from each of the four regions

of the country, using USDA designaons for southeast,

northeast, north central, and west.

We sent a preliminary invitaon to the CSA manager or

lead operator requesng parcipaon and explaining the

goals of the study. Any CSA could opt out. Three weeks

later, we followed up with a second invitaon. Surveys

were distributed to 2,100 addresses that did not opt out

of the study, 525 to each region. CSAs returned a total of

495 usable surveys, yielding an approximate 24 percent

eecve return rate. We collected usable responses

regionally from the northeast (100), north central (119),

southeast (87), and west (189), providing some dierences

in response rates by region.

Demographic characteriscs of the CSA managers

responding to the survey suggested a relavely large share

of female managers, younger, and generally well-educated.

These are summarized in table 1.

Table 1. CSA Manager Characteriscs

Gender

Female 259

Male 171

Age

18-24 7

25-34 102

35-44 116

45-54 92

55-64 87

65+ 26

Educaon

Less than high school 0

High school graduate or equivalent 16

Some college/associate’s degree 94

Bachelor’s degree 187

Graduate or professional degree 131

11

CSA Business Characteristics

Seasons in Operation

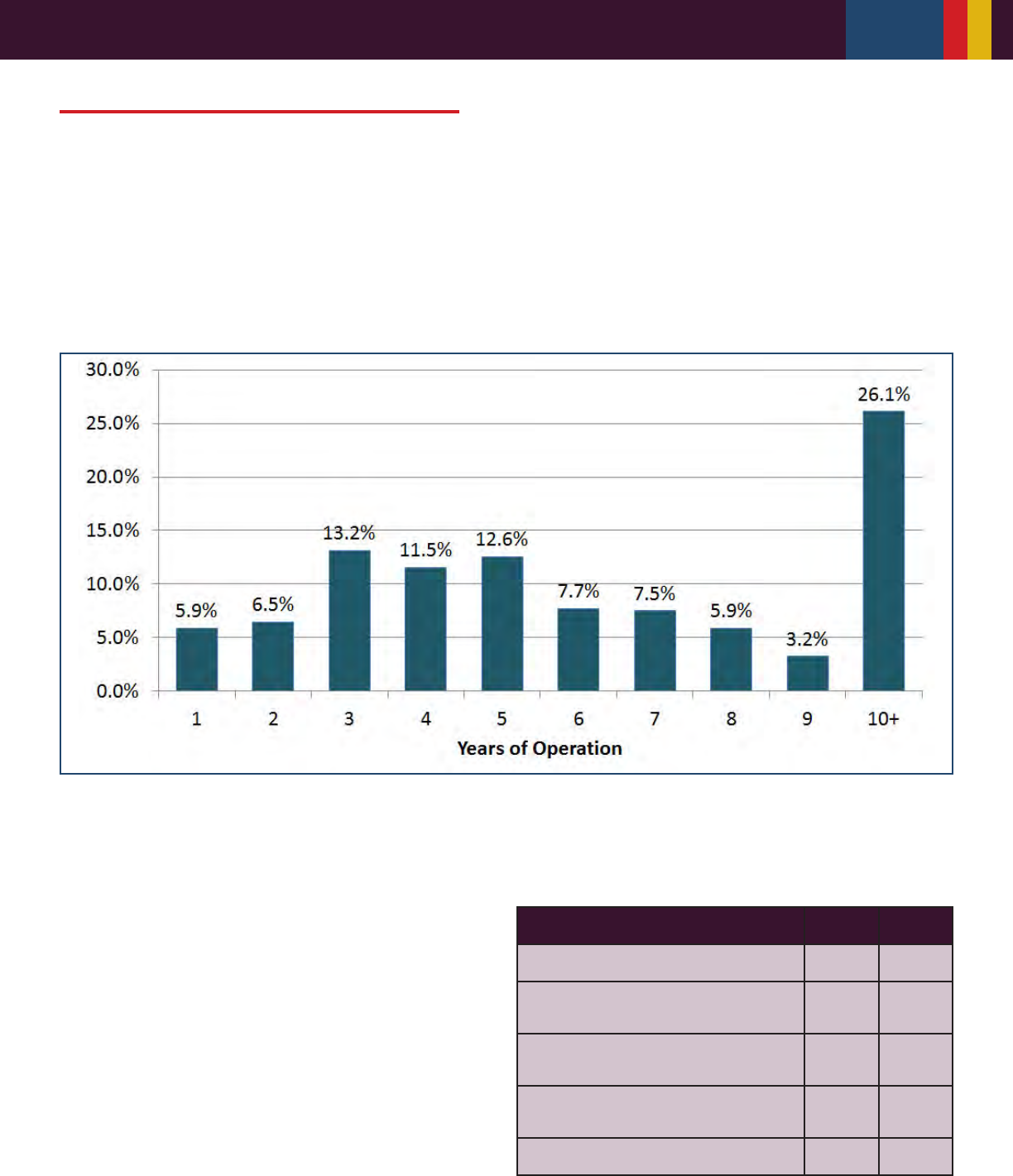

Many CSAs have been around for a while, over 26 percent

having been in business for over 10 years. The survey

targeted CSAs that were more established with a view

to looking at business trends over recent years. This

populaon was screened to only include those that

had been in existence for at least 2 years – a handful

of respondents indicated only one season of actual

producon. There is evidence of a cluster of CSAs that

have been around for 3-5 years and another for 10+ years.

The CSA typically involves a few years to establish to

plan for producon and to recruit shareholders. Figure 2

provides a summary of the distribuon of CSA seasons of

operaon.

Figure 2. How many seasons has your CSA been in operaon?

Characterization of Production Methods

Organic producon may have been the focus of CSAs early

in the CSA movement, but there has been a clear shi

to non-cercaon; only 27.2 percent indicated organic

cercaon of producon. Most managers indicate they

are implemenng producon systems at least according

to organic standards or cered (86.2 percent). Table 2

summarizes producon methods.

Table 2. How would you characterize your

producon methods?

Producon N* Percent

Cered organic 134 27.2%

According to organic standards, but

not cered

291 59.0%

Incorporate some organic along with

convenonal methods

61 12.4%

Primarily convenonal growing

techniques

7 1.4%

Total 493

12

Farm Sales Share from CSA

The average share of sales to the farm operaon coming

from the CSA was reported to be 53.2 percent. The

CSA was the major market channel for 58.1 percent

of those reporng. The role and changes with other

market channels is taken up in more detail later. Table 3

summarizes the share of farm sales from CSA.

Table 3. Percent of total farm sales comes from CSA

% Farm Sales from CSA N* Share of Responses

less than 25 120 25.5%

25-49 77 16.4%

50-74 117 24.9%

75-100 156 33.2%

Total Responses 470 100.0%

Average % of Farm Sales

From CSA

53.2

Shareholders Enrolled

CSA managers were asked to provide observaons in the

number of shareholders during the last 2 years and an

esmate for 2014. Average growth in parcipaon was +6

percent in 2013 and another +11 percent in 2014 (table

4). It is especially interesng to look at where they have

grown faster by proximity to urban areas. CSAs with more

of an e-commerce orientaon in another recent survey

were observed to be larger and growing at an even faster

rate. Huntley observed in CSAs parcipang with Small

Farm Central, 248 CSA farms that were also part of the

memberassembler.com E-commerce support network

reported larger share sizes among this group – averaging

213 shareholders with an average CSA income of $30,342

and an average 79 percent sales growth over 2013 sales

(Huntley, 2014).

Table 4. How many CSA patrons did you have

enrolled in…

2012 2013 2014

— Shareholders —

Average All CSAs 120.4 127.4 140.9

Although average shareholder size has been growing,

there are a large number of relavely small CSAs. The

average shareholders reported for 2014 was 140.9, but

the median response was 60 shareholders. Shareholders

numbers reported at each quinle suggest a wide range

between the smaller and larger CSAs – a long le tail in the

distribuon from the mean, as noted in gure 3. In 2014

61 percent of the CSAs reported under 100 shareholders

(down from 65 percent in 2012).

Figure 3. Distribuon of Shareholders Across Sample

13

CSA Proximity to Urban Communities

Farms ulizing the CSA distribuon model locate in a

variety of sengs. We explored the proximity of the

CSA to urban areas through the survey instrument.

Responses indicated a fairly even distribuon between

urban and rural locaons. Locaon will likely have

implicaons for distribuon and collaboraon tendencies,

as well as general shareholder growth, sales volume,

and opportunies to develop various markets. Table 5

summarizes CSA farm locaon informaon.

Table 5. Which of the following best describes

where your CSA is located?

Locaon N* Percent

Near (within 50 miles) a large city

(over 1 million)

104 24.2%

Near (within 50 miles) a small city

(250,000-1,000,000)

143 33.3%

Small town 114 26.5%

Countryside 69 16.0%

*N= 430

Regional analysis of the data suggests considerable

geographic dierences, summarized in table 6. CSA

shareholder size was larger in the Northeast and smaller

in the Southeast. Probably related, the average age of

the CSA was older in the Northeast and smaller in the

Southeast compared to the naonal average. Western-

based CSAs were slightly more likely to be cered organic,

and less so in the Southeast. CSAs in the Southeast were

more likely to be located within 50 miles of an urban

center, while rural sengs for producon were more likely

in the other regions.

4

Dierences in the expected protability of the CSA looking

ahead to the next 2 years were most striking between

those on the lower end of the range in the Northeast (39

percent) to the high end of the range in the North Central

region where 59.7 percent of respondents expected

increased sales. Sales growth expectaon is an important

variable and reects the manager’s percepon of

compeon, local demand, and opportunies to innovate.

4 A previous naonal survey of CSAs by Lass, Stevenson, Hendrickson, and Ruhf in 1999 noted 41% of the CSAs as cered organic – although this

was prior to the USDA cercaon. The median respondents sold 29 full shares and 23 half shares, and 70% reported operang on 49 acres or less

– at a median of 18 acres.

Table 6. CSA Business Characteriscs by Region

Region

*

Northeast

North

Central

Southeast West Overall

Average CSA Size (shareholders esmated for 2014) 203.8 154.5 105.9 125.7 144.8

Age of CSA

**

(years) 7.8 6.5 6.0 6.8 6.8

Cered Organic (%) 28.0% 22.7% 19.5% 32.8% 27.2%

Share in Urban Locaon

***

54.7% 54.7% 67.1% 56.5% 57.4%

Expect Increasing CSA Sales Next 2 Years 39.0% 59.7% 52.9% 51.3% 51.1%

N 100 119 87 189 495

*Regional designaons of various states in this study follow those made by USDA – Northeast, North Central, Southeast, and West.

**The average age of CSAs by region used an imputed value of 13 years for the categorical variable “10+ years” for the purposes of esmang an

average over each group.

***A signicant number of respondents reported their CSA locaon close to urban populaon centers. Urban here means located near (within 50

miles) of a large city – over 1 million or small city – 250,000 to 1,000,000. Specic responses related to locaon by region are reported as follows:

Northeast North Central Southeast West All

Urban 47 58 47 95 247

Total 86 106 70 168 430

14

Other Market Channels for CSAs

The CSA markeng channel was clearly a substanal focus

and priority among those managers responding to the

survey. Many CSAs ulize addional market channels

to diversify and to complement their CSA market. Low

and Vogel (2011) discuss many of the issues relang to

direct and intermediated markets. This survey did not

explore the specic use of and relaonship to intermediary

market partners, although specialty wholesalers and food

hubs have certainly ventured into the CSA subscripon-

type delivery model, sourcing from local producers and

aggregang products for delivery. Wholesalers have

increasingly partnered with growers to beer serve area

grocers and restaurants with local products. It is evident,

however, that other direct markeng channels (community

farmers markets and on-farm retail) are more common

markeng venues for CSAs.

Table 7 summarizes the level of acvity that survey

respondents reported in various markeng channels.

One of the more striking results was the extent to which

CSAs sell to restaurants – over half of them. The specic

use of direct-store deliveries versus using intermediaries

in delivery was not explicitly addressed, although it is

not surprising to see restaurants and farmers markets

dominate the list of alternave market outlets for CSAs

given the complementary distribuon strategies typical

of CSAs.

We conducted an analysis of the data to explore possible

dierences in market channel strategy by urban versus

rural locaon of the CSA. This value does not necessarily

correspond to actual sales by channel, which may sll

be dierent by business locaon. But, as noted in the

summary on table 8, the markeng channel mix broken

out by proximity to populaon centers seems to be

approximately the same with only slight variaons.

Table 7. Indicate which markets you used to sell

farm products

Market N* Percent

CSA 469 100.0

Farmers market 304 64.8

Restaurants 258 55.0

On-farm retail 194 41.4

Grocery 180 38.4

School/instuons 92 19.6

Contract to processors 17 3.6

Aucon sales 12 2.6

Other (please specify) 76 16.2

Table 8. Market Channel Parcipaon by CSA Locaon

Locaon Near large city Near small city Small town Countryside

CSA 100% 100% 100% 100%

Community farmers market 60% 69% 69% 68%

On-farm retail market 47% 37% 35% 56%

Grocery 32% 38% 44% 43%

Restaurants 58% 61% 54% 47%

Schools/Instuons 19% 17% 26% 19%

Aucon sales 4% 2% 2% 0%

Contract to processors 3% 5% 4% 3%

15

Managers were asked to provide an outlook for the various

market channels, looking ahead to sales changes in the

various markets over the next 2 years. Managers were

provided a “does not apply” opon for each market where

they either may not be selling or don’t have a good feel for

the channel. The majority of responses expected increases

in each of the market channels with the excepon of

aucon markets.

Sales to schools/instuons were noted most frequently

as being expected to increase, followed by on-farm retail,

restaurants, grocery, CSAs, contracts to processors, and

farmers markets. Only about 10 percent or fewer expected

to see decreasing sales in any of these markets. Table 9

summarizes these observaons.

Table 9. How do you expect sales to change in these markets over the next 2 years?

Sales Change

CSA

Channel

Community

Farm Market

On-farm

Retail

Market

Wholesale

to Grocery

Wholesale

to

Restaurant

Wholesale

to Schools &

Instuons

Aucon

Contract to

processors

Decreasing 51 33 8 24 31 6 5 4

About the

same

163 123 78 72 92 33 8 16

Increasing 253 175 158 132 182 98 5 23

N 467 331 244 228 305 137 18 43

By Percent

Decreasing 10.9% 10.0% 3.3% 10.5% 10.2% 4.4% 27.8% 9.3%

Same 34.9% 37.2% 32.0% 31.6% 30.2% 24.1% 44.4% 37.2%

Increasing 54.2% 52.9% 64.8% 57.9% 59.7% 71.5% 27.8% 53.5%

Changes in CSA Products,

Business Functions, and

Profitability

The CSA model has evolved in recent years through

a variety of producon and markeng innovaons.

Part of the survey explored specic addions to the

tradional CSA model or whether the CSA has observed a

connuaon of pracces that were commonly associated

with the CSA business model.

Changes to Products and Production

Managers were asked to reect on changes in funconal

aspects of their CSA from when it began, focusing

parcularly on a variety of producon-oriented acvies,

indicang whether the type of acvity was decreasing,

increasing, or did not apply. Specically, we examined

changes in scale, the variety of products oered,

incorporaon of processed products, season extension,

sourcing from other producers, on-farm shareholder

acvies, and share packing on the farm. These are

summarized in table 10.

16

Table 10. Manager Response to: Changes in Your CSA Operaon Since It Began

CSA Producon Funcon

Decreased

a lot

Decreased

some

Stayed

about the

same

Increased

some

Increased

a lot

N

Scale and variety of products

oered

7 22 94 194 126 443

1.6% 5.0% 21.2% 43.8% 28.4%

Processed products oered

2 8 76 101 28 215

0.9% 3.7% 35.3% 47.0% 13.0%

Season extension technologies

2 3 97 178 102 382

0.5% 0.8% 25.4% 46.6% 26.7%

Product sourcing from other

producers

10 10 74 98 31 223

4.5% 4.5% 33.2% 43.9% 13.9%

On-farm shareholder acvies

9 30 140 99 25 303

3.0% 9.9% 46.2% 32.7% 8.3%

Share packing on the farm

13 9 176 45 33 276

4.7% 3.3% 63.8% 16.3% 12.0%

Note: Percent represents of those that indicated the funcon applied to their CSA

The trend toward increasing scale and variety of products

was fairly pronounced and widely applicable. More than

28 percent of the CSAs indicated that the scale and variety

of products oered had increased a lot since their CSA

started, and 72 percent indicated it had at least increased

somewhat. This development suggests that CSAs are

discovering certain scale and scope economies in their

product lines and are diversifying their product oerings

more over me. The addion of processed products was

not as widespread, but certainly increasing among those

CSAs where processed product had been introduced.

Season extension technologies were also widely ulized

and were increasing in use by more than 72 percent of

the CSAs using them. Season extension technologies help

expand both the scale and scope of products available to

shareholders.

Product sourcing from other producers was less common,

although the data suggest this pracce is increasing

somewhat. This is an alternate strategy to achieving

product diversicaon and scale. Parcipants in focus

group interviews voiced mixed opinions about mul-farm

CSAs, parcularly related to quality control, reputaon

and customer relaons management, and dilung the

farmer-shareholder connecon (see more on this topic in

5 Only 4 of the 200 CSAs surveyed by Woods et al in 2009 used workshare or barter agreements.

the Elmwood Stock Farm case study). Other CSA operators

were able to very eecvely use mul-farm scale and

scope to access markets they would not otherwise be able

to achieve on their own (Penn’s Corner Farm Alliance).

On-farm shareholder acvies that invite CSA members

to visit and/or work on the farm is an historical pracce

of CSAs commonly used in the spirit of building the

community part of community supported agriculture.

While many CSA operaons sll incorporate this to some

extent, nearly a third of the CSAs surveyed indicated that

these types of acvies didn’t apply to their operaon.

Shareholder packing on the farm and other similar work-

for-product type of arrangements, once a common part of

the CSA, are similarly becoming less commonplace.

5

A summary of these producon acvies across regions

and between newer (in operaon 5 years or fewer) is

provided in table 11. Key regional dierences appear

to relate to observed changes in season extension –

substanally greater frequency of increases in the North

Central region of the United States and less frequent in the

Northeast. This result may be due to Northeast producers

either already having implemented some of these season

extension pracces or, possibly, reects dierences in

producon and markeng cultures or observed demand

between the regions (see table 6).

17

Younger CSAs seem more inclined to adopt processed

products as part of their markeng mix and more likely

to favor sourcing from other producers than their older

peers Another somewhat counter-intuive observaon is

the indicaon that younger CSAs are more likely to report

increasing use of on-farm shareholder acvies than

CSAs that have been in operaon longer than 5 years. It

is unclear whether or not these dierences in preference

reect dierences in targeted markeng strategies or

simply reect changes that naturally occur during the

business life cycle of a CSA.

Changes to Business and Marketing

CSA managers were also asked to reect on how a series of

CSA business funcons have changed since the incepon

of their business. Specically, managers were asked

to consider the changes to the sales and protability

of their CSA associated with adding share purchase

opons, cooperave markeng, exible payment opons,

shareholder turnover, shareholder communicaons, and

web-based sales. We then asked managers to summarize

the overall contribuon of the CSA to overall farm sales

and the overall protability of the CSA. An overall

summary from all CSAs to changes in these business

funcons is summarized in table 12.

Table 11. Proporon Indicang Producon Funcon “Increasing Some” or “Increasing a Lot” by Region and

CSA Age

Region CSA Age

CSA Producon Funcon NE NC SE W

Newer

CSA

Older

CSA

Scale and variety of products oered 71.6% 76.1% 75.7% 68.6% 71.0% 73.5%

Processed products oered 60.0% 56.6% 64.9% 60.0% 65.5% 54.3%

Season extension technologies 61.8% 85.0% 73.8% 71.0% 70.3% 76.5%

Product sourcing from other producers 55.6% 58.6% 58.8% 58.1% 63.3% 53.6%

On-farm shareholder acvies 40.3% 34.1% 46.3% 44.1% 47.6% 34.8%

Share packing on the farm 27.1% 28.0% 31.0% 28.0% 26.5% 29.9%

Note: Percent represents of those indicang the producon funcon applies to their operaon. Increasing is relave and not an absolute measure

here. “Newer CSA” is dened here as having been in operaon 5 years or less.

18

Table 12. Consider the following potenal changes to your CSA sales and protability since it began – please

indicate where they may apply

CSA Business Funcon

Decreased

a lot

Decreased

some

About the

same

Increased

some

Increased

a lot

N

Share purchase opon

(part-season or special shares)

6 20 135 144 61 366

1.6% 5.5% 36.9% 39.3% 16.7%

Markeng cooperaon with other producers

7 11 103 104 26 251

2.8% 4.4% 41.0% 41.4% 10.4%

Flexible payment (i.e., installment plans)

2 9 187 138 46 382

0.5% 2.4% 49.0% 36.1% 12.0%

Shareholder turnover

13 48 276 68 20 425

3.1% 11.3% 64.9% 16.0% 4.7%

Communicaon with shareholders

0 11 174 184 66 435

0.0% 2.5% 40.0% 42.3% 15.2%

Web-based sales

1 3 92 112 82 290

0.3% 1.0% 31.7% 38.6% 28.3%

Contribuon of CSA to overall farm prots

13 38 167 146 71 435

3.0% 8.7% 38.4% 33.6% 16.3%

Overall protability of CSA

11 26 157 197 44 435

2.5% 6.0% 36.1% 45.3% 10.1%

Note: Percent represents of those that indicated the funcon applied to their CSA

Table 13 summarizes these business funcons across

regions and CSA operaon age. There was some regional

variaon with more frequent reports of increases in

shareholder turnover issues in the Southeast, and

relavely greater increases in web-based sales, overall CSA

protability, and the contribuon of the CSA to overall

farm prots in the North Central region. Meanwhile,

greater CSA age seems to be posively associated with

increases in communicaon with shareholders and web-

based sales.

Table 13. Proporon Indicang Business Funcon “Increasing Some” or “Increasing a Lot” by Region and

CSA Age

Region CSA Age

CSA Business Funcon NE NC SE W

Newer

CSA

Older

CSA

Markeng cooperaon with other producers 45.8% 47.9% 55.3% 56.4% 51.6% 52.0%

Flexible payment opons (i.e., installment plans) 43.2% 53.0% 49.1% 47.0% 46.0% 50.3%

Shareholder turnover 22.6% 16.8% 28.2% 19.0% 19.0% 22.4%

Communicaon with shareholders 55.2% 58.7% 52.8% 59.9% 53.6% 61.4%

Web-based sales 55.8% 74.3% 69.6% 66.1% 63.8% 70.2%

Contribuon of CSA to overall farm prots 47.1% 57.1% 52.1% 45.9% 51.6% 48.1%

Overall protability of CSA 48.8% 65.1% 54.1% 53.2% 53.9% 56.9%

Note: Percent represents of those indicang the producon funcon applies to their operaon. Increasing is relave and not an absolute

measure here. “Newer CSA” is dened here as having been in operaon 5 years or less.

19

Evaluating Local Food Market

Demand, Competition, and

Shareholder Recruitment

Market demand and compeon for local food in a CSA’s

primary trade area can substanally inuence the kind of

business strategies the CSA employs, its mix of product

oerings, and its emphasis on CSA-based markeng

compared to other distribuon opons. Demand and

compeon measures presumably have an impact on

shareholder recruitment and the staying power of the

CSA. In the naonal survey, CSA managers were asked to

evaluate the overall demand situaon in their immediate

trade area and to also rank the relave importance of

exisng competors for local food sales. Geographic

dierences related to regional locaon and proximity to

urban centers were also considered.

In general, CSA managers were very opmisc about

demand for local food in their market area. The

percentages of managers expecng connued demand

growth was very strong – around 25 percent reporng

that they expected demand in their area to increase

signicantly, and 85 percent expecng demand to increase

to some degree. Only 3.5 percent of surveyed managers

indicated that they expected the current level of demand

to decline. These overall results are summarized in

table 14.

Comparisons of percepons of demand for local food

varied slightly by region, proximity to urban areas, and

age of the CSA. CSA managers in the Northeast were

more likely to report local food demand as unchanging or

declining. Managers of younger CSAs and CSAs in rural

locaons also reported less robust demand for local food

than their industry peers. This could partly reect arion

of older CSAs in less-than-desirable market situaons

or older CSAs that have adapted their business over

me to beer t the current market situaon. Table 15

summarizes these percepons.

Table 14. How would you rate the demand for local food in your market area?

Declining

signicantly

Declining

somewhat

Staying

about the

same

Increasing

somewhat

Increasing

signicantly

N

4 11 48 257 106 426

0.9% 2.6% 11.3% 60.3% 24.9%

Note: Percent represents of those that indicated they had a basis for knowing demand for local food

Table 15. Local Food Demand Percepons by Region, Populaon Proximity, and CSA Age

Demand Changes NE NC SE W Rural Urban

Newer

CSA

Older

CSA

Same or declining 22.4% 14.0% 14.1% 11.7% 18.8% 11.6% 17.6% 11.9%

Increasing Somewhat 55.3% 62.6% 57.7% 62.6% 58.6% 61.6% 60.6% 60.0%

Increasing Signicantly 22.4% 23.4% 28.2% 25.8% 22.7% 26.9% 21.8% 28.1%

N 85 107 71 163 181 242 216 210

20

Another important issue facing CSA operators is the level

of nearby compeon for the consumer’s local food

dollar in their immediate trade area. To obtain a beer

understanding of how CSAs view their primary sources of

market compeon, surveyed CSA managers were asked

to rank the relave importance of emerging sources of

compeon facing their CSA. The overall rankings are

summarized in table 16. New CSAs entering the trade area

and the expansion of established CSAs in the same trade

area were ranked as the highest sources of compeon,

followed by farm markets. Natural food stores that

typically oer both organic and local products followed

next in the rankings roughly equal with tradional and

high-end grocers oering local food. Restaurants selling

local food and home food delivery services ranked near

the boom of the list for emerging sources of market

compeon.

Interesngly, several of the survey respondents included

wrien comments regarding compeon for local food

sales, nong that in their area they perceived lile

threat from compeon in the marketplace, as the

emergence/expansion of other CSAs and the increased

number of retailers oering local foods actually served

to raise awareness of local food among consumers and

subsequently drove up interest in CSA parcipaon.

Consequently, they saw the overall expansion in local

food market outlets as essenally complementary to

their business rather than a source of direct compeon.

Other industry representaves noted the importance of

establishing a crical mass of CSA operaons in order to

implement related programs that served to boost demand

(Fair Share Coalion and wellness voucher programs, for

example).

Percepons about compeon are quite variable across

geographic regions, proximity to populaon centers, and

between newer and more established CSAs. CSAs in the

Northeast and North Central regions idened new CSAs

entering the market as the most signicant source of

emerging compeon, those in the Southeast and Western

regions ranked farm markets were ranked as the most

signicant source of market compeon for local foods.

Home food delivery services were rated as a source of

more signicant inuence on market compeon in the

Western region than anywhere else in the Naon.

Table 16. Ranking of the Signicance of Emerging

Sources of Compeon Relang to the CSA

Business

Mean

rank

Standard

deviaon

New CSAs entering the market 3.47 2.16

Farm markets 3.48 2.02

Established CSAs Expanding 3.90 2.23

Natural food stores 4.65 1.99

Other home food delivery

services

4.65 2.47

Tradional grocers oering

local food

4.73 2.14

High-end grocers 5.25 2.06

Restaurants oering local food 5.87 2.13

Note: (rate highest = 1 to lowest = 8); N = 433

Dierences were noted between rural and urban markets

as well. Managers of rural CSAs ranked farm markets

as a greater inuence on local food market compeon

than urban markets, while urban markets ranked home

delivery services and high-end grocers higher than their

rural counterparts (using t-tests comparing average rangs

between the two groups). Newer CSAs rated natural food

stores as relavely greater sources of market compeon

than older CSAs while older CSAs rated home delivery

services as greater sources of market compeon than

younger CSAs. These comparisons are highlighted in

table 17.

21

Table 17. Emerging Compeon Rankings by Region, Populaon Proximity, and CSA Age

NE NC SE W Rural Urban

Newer

CSA

Older

CSA

New CSAs entering market 3.01 3.27 3.65 3.76 3.33 3.57 3.55 3.40

Farm markets 3.37 3.42 3.56 3.55 3.26 3.64** 3.55 3.42

Established CSAs expanding 3.66 3.66 4.18 4.06 3.83 3.98 3.74 4.07

Natural food stores 4.67 4.59 4.94 4.54 4.52 4.76 4.43 4.87**

Other home food delivery services 5.21 4.64 4.77 4.33 4.96 4.44** 4.87 4.43*

Tradional grocers oering local food 5.06 4.59 4.59 4.70 4.86 4.62 4.67 4.78

High-end grocers 5.06 5.74 4.76 5.24 5.54 5.02** 5.28 5.21

Restaurants oering local food 5.95 6.09 5.54 5.82 5.69 5.98 5.91 5.82

Note: t-tests were conducted for mean ranking levels for each market type between two group sets for rural-urban and newer-older CSAs.

* and ** indicate stascal signicance at the 10% and 5% levels.

Following the quesons on market demand and

compeon, managers were asked to evaluate shareholder

recruitment for their CSA for 2014 compared to previous

years. Overall, about an equal number reported

recruitment to be more dicult and less dicult. Table 18

summarizes these results.

As illustrated in table 19, shareholder recruitment was

explored across regions, rural/urban areas, and CSA age,

and revealed relavely minor dierences in responses.

The CSAs in the North Central and Southeast regions

seemed to have generally less diculty with recruitment,

consistent with the demand observaons noted earlier.

Newer CSAs also expressed slightly less recruitment

diculty – 35 percent reported recruitment to be

“somewhat less” or “much less” dicult in 2014 compared

to previous years, as opposed to 20 percent among

managers of older CSAs. This laer result is not surprising

given that older CSAs presumably have to deal more with

replacement due to subscriber arion in their designated

market areas.

Table 18. CSA shareholder recruitment for 2014

compared to previous years has been….

Recruitment Diculty N Percent

Much less dicult 43 11.2%

Somewhat less dicult 62 16.1%

About the same 180 46.9%

Somewhat more dicult 78 20.3%

Much more dicult 21 5.5%

N = 384 does not include 12 that indicated queson doesn’t apply.

22

Table 19. CSA shareholder recruitment for 2014 by Region, Urban Proximity, and CSA Age

Recruitment Diculty NE NC SE W Rural Urban

Newer

CSA

Older

CSA

Much less dicult 8% 16% 16% 8% 13% 10% 14% 8%

Somewhat less dicult 13% 20% 17% 15% 16% 16% 21% 12%

About the same 49% 39% 44% 52% 48% 46% 43% 51%

Somewhat more dicult 22% 18% 22% 20% 17% 23% 18% 23%

Much more dicult 8% 7% 2% 5% 5% 6% 4% 7%

N 76 88 64 156 164 220 194 190

Cooperation Potential for

Multi-Farm CSAs

CSA business model innovaons take many forms. They

include business models built on a foundaon of mul-

farm sourcing and/or regional CSA cooperaon to either

access non-tradional markets or build scale and scope

economies to overcome distribuon and promoon

challenges.

There are a variety of ways farms can collaborate to

pursue their CSA mission with both informal and formal

partnerships, ranging from informal shared methods of

distribuon to the creaon of formalized cooperaves

like those featured as a case study in this report - Penn’s

Corner Farm Alliance and the FairShare Coalion in

Wisconsin.

In the survey we explored a series of prospecve

CSA business acvies that could potenally involve

cooperaon, focusing parcularly at the level of CSA

manager interest in engaging in a specic range of

cooperave acvies. The survey did not aempt to

explore an exhausve list of potenal business funcons

but rather focused on selected cooperave acvies

observed in earlier CSA site visits. Specically, the

prospecve cooperave business acvies addressed

in the survey included adding specialty food products,

supplemenng inventory as needed, shared delivery

pracces, shared educaonal resources, low-income

voucher programs, health and wellness voucher programs

,6

and regional recruitment fairs.

Among those CSAs that were already engaged in mul-

farm acvies, the most common mul-farm acvies

already being pursued included supplemenng new

specialty products (27.8 percent) and supplemenng

inventory when short (21 percent). Relavely small

numbers of CSA reported cooperang on recruitment

fairs (15.9 percent), low-income voucher programs (14.4

percent), and shared educaonal programs (11.4 percent).

Interest in pursuing selected mul-farm collaboraons

was relavely high for several of the mul-farm acvies

listed in the survey – parcularly health and wellness

vouchers and low-income voucher programs, where

the most common response was “very interested.”

Shared educaonal resources and shared recruitment/

promoonal fairs also indicated having at least possible

interest (or current mul-farm parcipaon) from about 85

percent of the managers. In addion, joint markeng with

other producers was on the increase, as noted elsewhere

in this survey (see table 12).

Acvies where there was demonstrably less interest

in mul-farm cooperaon included shared delivery and

supplemenng delivery when short (response was “not

interested”). Interest and parcipaon in these selected

mul-farm acvies is summarized in table 20.

6 See also Greg Jackson, Amanda Raster, and Will Shauck (2011) for an extended discussion of the health insurance rebate iniaves in

Wisconsin.

23

Table 20. Please indicate your interest in cooperang with other producers on aspects of your CSA

Acvity

Not

interested

Possibly

interested

Very

interested

Already

doing this

N

Adding specialty products I don’t carry

104 161 44 119 428

24.3% 37.6% 10.3% 27.8%

Supplemenng inventory when short

166 124 48 90 428

38.8% 29.0% 11.2% 21.0%

Shared delivery

196 149 57 27 429

45.7% 34.7% 13.3% 6.3%

Shared educaonal resources

68 193 119 49 429

15.9% 45.0% 27.7% 11.4%

Low- income voucher programs

77 136 155 62 430

17.9% 31.6% 36.0% 14.4%

Health and wellness voucher programs

76 139 188 28 431

17.6% 32.3% 43.6% 6.5%

Area CSA promoonal recruitment fairs

63 178 120 68 429

14.7% 41.5% 28.0% 15.9%

24

Discussion and Conclusions From the

CSA Manager Survey

T

his study represents an important documentaon of

trends in the CSA business model. The CSA concept

has been around for many years. Markets, technology, and

markeng strategies, however, have changed, including

new opportunies to connect with demand for local food

and for farmers to innovate through new products and

new forms of collaboraon. The tradional CSA consumer

has become more diverse, moving beyond a focus on

cered organic products and close engagement with

the farm.

The data further reveals substanal regional dierences

in how CSAs are operang and performing. While most

managers point to steady shareholder growth, expected

connued CSA sales growth and protability, and strong

demand in their markets for local products, there is

evidence of variability in this outlook regionally and based

on where the farm may be located.

The CSA business model has evolved signicantly,

as entrepreneurs and market forces have opened

opportunies for the implementaon of the model

in ways quite unlike the early CSA operaons. New

products, season extensions, mul-farm collaboraons,

new shareholder groups, markeng collaboraons with

dierent organizaons, innovave aggregaon and

delivery strategies, new urban producon connecons,

and health and wellness alliances are among the current

trends reshaping the CSA business.

25

The Changing CSA Business Model –

Six Case Studies

T

he CSA markeng model connues to be adapted

to t many market circumstances. There is room

for a diversity of strategies – single farm, mul-farm,

co-operavely owned, and even non-farm owned. There

is room for a diversity of market targets, including the

tradional shareholder who prefers organic produce, but,

increasingly, the focus is on using the CSA as a way to

facilitate consumer access to local foods in general. Farms

and groups of farms are becoming increasingly innovave

nding ways to reach non-tradional market segments

with CSA shares. This includes incorporang e-commerce,

adding products through season extensions, adding

shares for alternave product lines beyond tradional

produce, and working with urban, health/wellness, and

community development partners to access lower income

shareholders. The Madison, WI, FairShare CSA Coalion

has ulized wellness plan vouchers to substanally

expand demand for shares among local farmers and has

collecvely promoted and provided quality standards

crical to maintaining the program. Denver, CO, area

CSAs have pursued many of their own innovaons with

CSA farmers by creang peer-learning opportunies and

collaborang with city planners and urban markets. Non-

farm aggregaon models to deliver CSA shares have been

emerging as well, including the Fair Share Combined

CSA in St. Louis, MO, where a small food retailer built a

CSA business around a shared vision for local foods with

area farmers.

These case studies more deeply illustrate observaons

noted from the naonal survey on CSA business

innovaons and markeng trends. The study doesn’t

propose to document every possible innovaon in

products sold using the CSA model or provide the full

scope of business hybrids that are in some way related

to the original CSA concept. Rather, the study provides

documentaon of innovaons and opportunies

recognized across a number of CSA communies that could

potenally be adapted to other farms or communies

with a shared vision. There are many excellent examples

of CSA innovators. These parcular cases were selected

to illustrate some of the changes taking place and to look

with the case subjects at the trajectory of the CSA concept.

The compeve landscape is also changing. In some

cases, this is a posive for farm-based CSAs; in other cases,

it presents a threat. These ideas are examined across a

variety of business models and markets.

A case-based approach can be parcularly useful for

gaining producer and agency perspecves on innovaons

in the CSA markeng model. We selected a set of CSAs

naonally that represented tradional single farm models;

cooperaves/mul-farm CSAs; low-income, consumer-

targeted CSAs; and mul-farm innovaons targeng

unique consumer segments with a unique health and

wellness markeng partner. We also included CSAs

associated with urban market innovaons, and a for-prot

food hub concept that ulized a CSA aggregaon and

distribuon model. These cases were selected to provide

diverse market and geographic perspecves. Through a