TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page i

Heinemann

361 Hanover Street

Portsmouth, NH 03801–3912

www.heinemann.com

Offices and agents throughout the world

© 2013 by Harvey Daniels and Nancy Steineke

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any

electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems,

without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote

brief passages in a review, with the exception of reproducible pages, which are

identified by the Texts and Lessons for Teaching Literature credit line and may be

photocopied for classroom use only.

“Dedicated to Teachers” is a trademark of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

The authors and publisher wish to thank those who have generously given permission

to reprint borrowed material:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Daniels, Harvey.

Texts and lessons for teaching literature : with 65 fresh mentor texts from Dave

Eggers, Nikki Giovanni, Pat Conroy, Jesus Colon, Tim O’Brien, Judith Ortiz Cofer, and

many more / Harvey “Smokey” Daniels and Nancy Steineke.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-325-04435-4

ISBN-10: 0-325-04435-X

1. Literature—Study and teaching (Middle school). 2. Literature—Study and

teaching (Secondary). 3. Content area reading. I. Steineke, Nancy, author.

II. Title.

LB1575.D36 2013

807.12

—dc23 2012046368

Editor: Tobey Antao

Production management: Sarah Weaver

Production coordination: Patty Adams

Cover and interior design: Lisa Anne Fowler

Typesetter: Gina Poirier Design

Manufacturing: Steve Bernier

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

17 16 15 14 13 ML 1 2 3 4 5

Choices Made by Jim O’Loughlin. Copyright © 2009 by Jim O’Loughlin. Reprinted by

permission of the Author.

“Tuning” from The Winter Room by Gary Paulsen. Copyright © 1989 by Gary Paulsen.

Published by Scholastic. Reprinted by permission of Flannery Literary Agency.

continues on page vii

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page ii

CHAPTER 1

Welcome 1

CHAPTER 2

How to Use This Book 6

CHAPTER 3

Sharing Literature Aloud 18

3.1

Pair Share

18

“Choices Made” by Jim O’Loughlin

21

3.2

Teacher Read-Aloud

22

“Tuning,” Preface from The Winter Room by Gary Paulsen

25

3.3

One-Minute Write

26

“The Limited” by Sherman Alexie

28

3.4

Teacher Think-Aloud

29

“Untitled” by Dan Argent

32

3.5

Partner Think-Aloud

33

“There’s No Place Like It” by Dean Christianson

35

“Death in the Afternoon” by Priscilla Mintling

36

CHAPTER 4

Smart-Reader Strategies 37

4.1

Text Annotation

37

“Afterthoughts” by Sara Holbrook

41

“The Boy They Didn’t Take Pictures Of” by Dave Eggers

42

4.2

Connections and Disconnections

43

“Ambush” by Roger Woodward

46

4.3

Drawing Text Details

47

“Ascent” by Michael Salinger

50

4.4

Reading with Questions in Mind

51

“Noel” by Roger Plemmons

54

4.5

Inferring Meaning

56

Assorted Six-Word Memoirs

57

4.6

Tweet the Text

59

“The Sweet Perfume of Good-Bye” by M. E. Kerr

62

III

Contents

CONTENTS

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page iii

CHAPTER 5

Lively Discussions 65

5.1

Written Conversation

66

“Rose” by John Biguenet

71

5.2

Thirty-Second Look

73

Mining Village by Stevan Dohanos

76

5.3

Follow-Up Questions

77

“Deportation at Breakfast” by Larry Fondation

81

5.4

Save the Last Word for Me

83

“Stingray” by Michael Salinger

86

5.5

Literature Circles

89

“The Chimpanzees of Wyoming” by Don Zancanella

94

CHAPTER 6

Closer Readings 103

6.1

Denotation/Connotation

103

“Chameleon Schlemieleon” by Patric S. Tray

107

6.2

Setting the Scene

108

Wanderer in the Storm by Carl Julius von Leypold

111

6.3

Two-Column Notes

112

“Forwarding Order Expired” by John M. Daniel

116

6.4

Point-of-View Note Taking

117

“Accident” by Dave Eggers

120

6.5

Seeing a Character

121

Untitled by James Henry Moser

124

6.6

Metaphorically Speaking

126

“Fight #3” by Helen Phillips

129

“How the Water Feels to the Fishes” by Dave Eggers

130

6.7

Rereading Prose

131

“The Father” by Raymond Carver

136

6.8

Rereading Poetry

137

“Ducks” by Michael Salinger

140

CHAPTER 7

Up and Thinking 141

7.1

Find an Expert

141

“The Horror” by Dave Eggers

148

7.2

Text on Text

149

“I Am From” by Lorian Dahkai

152

7.3

Frozen Scenes

153

“This Is How I Remember It”

by Betsy Kemper (mature)

157

IV

Contents

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page iv

7.4

The Human Continuum

158

“Little Things Are Big” by Jesus Colon

161

7.5

Character Interview Cards

163

“The Container” by Deb Olan Unferth

167

CHAPTER 8

Literary Arguments 169

8.1

Take a Position

169

“We? #5” by Helen Phillips

172

8.2

Finish the Story

173

“Little Brother

TM

” by Bruce Holland Rogers

177

8.3

Arguing Both Sides

180

“The Wallet” by Andrew McCuaig

185

CHAPTER 9

Coping with Complex and Classic Texts 187

9.1

Literary Networking

187

“The Storyteller” by Saki

192

9.2

Characters Texting

196

“Persephone and Demeter” by Thomas Bulfinch

199

9.3

Opening Up a Poem

203

“The Listeners” by Walter de la Mare

206

9.4

Stop, Think, and React

207

“The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe

211

9.5

Reading with Expression

217

“Witches’ Chant” from Macbeth by William Shakespeare

220

CHAPTER 10

Text Set Lessons 223

1

Memory

224

“Kennedy in the Barrio” by Judith Ortiz Cofer

226

Excerpt from the Warren Commission Report (1964)

227

Announcement of President Kennedy’s Death

by Walter Cronkite (available online)

2

Citizenship

229

“Canvassing for the School Levy” by Sara Holbrook

231

3

Life Stories

232

“Nikki-Rosa” by Nikki Giovanni

235

“Nikki Giovanni Biography” from Wikipedia

236

“Giovanni Timeline” by Nikki Giovanni (available online)

V

Contents

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page v

4

Mothers and Daughters

237

“Persephone and Demeter”

by Thomas Bulfinch

199

(Lesson 9.2)

“Mother #1” by Helen Phillips

241

“Mother Disapproved of Him” (mature)

by Rita Mae Brown

242

5

Narcissism

244

Narcissus by Caravaggio (available online)

“Narcissus and Echo” (adapation) by Ovid

246

“Narcissism” from Wikipedia

248

“The Stag and His Reflection” by Aesop

249

6

Labels

250

“Labels” by Sara Holbrook

252

“Sitting Bull Returns” at the Drive-In

by Willard Midgette

253

“Sure You Can Ask Me a Personal Question”

by Diane Burns

254

“On Making Him a Good Man by Calling Him

a Good Man” by Dave Eggers

256

“Speech at the U.S. Capitol” by Mandeep Chahal

257

7

Abuse

260

“Dozens of Roses: A Story for Voices”

by Virginia Euwer Wolff

263

“The Wallet” by Andrew McCuaig

185

(Lesson 8.3)

“My Father” (mature) by Pat Conroy

265

8

Soldiers and Heroes

267

“Broadcaster Refuses to Label Dead

Soldiers ‘Heroes’” by Lee Terrell

271

The Advance Guard, or The Military Sacrifice

(The Ambush) by Frederic Remington

272

“Three Soldiers” by Bruce Holland Rogers

273

“The News from Iraq” by Sara Holbrook

274

“Heroes” by Tim O’Brien

277

CHAPTER 11

Keeping Kids at the Center

of Whole-Class Novels

279

CHAPTER 12

Extending the Texts and Lessons 294

Appendix How the Lessons Correlate

with the Common Core Standards 300

Works Cited 302

VI

Contents

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page vi

“The Limited” from War Dances, copyright © 2009 by

Sherman Alexie. Used by permission of Grove/Atlantic,

Inc., and Nancy Stauffer Associates.

“Untitled” by Dan Argent from New Scientist Magazine,

August 2009. Copyright © 2009 Reed Business

Information–UK. All rights reserved. Distributed

by Tribune Media Services.

“There’s No Place Like It” by Dean Christianson, “Death in

the Afternoon” by Priscilla Mintling, and “Chameleon

Schlemieleon” by Patric Tray from World’s Shortest Stories,

edited by Steve Moss. Copyright © Jan. 1, 1998. Reprinted by

permission of Running Press Book Publishers, a member of

the Perseus Books Group via Copyright Clearance Center.

“Accident,” “The Boy They Didn’t Take Pictures Of,” “How

the Water Feels to the Fishes,” “The Horror,” and “On

Making Him a Good Man by Calling Him a Good Man”

from How the Water Feels to the Fishes: 145 Stories in a

Small Box by Dave Eggers. Copyright © 2007 by Dave

Eggers. Published by McSweeney’s, San Francisco.

Reprinted by permission of the Author.

Poems: “Afterthoughts,” “Canvassing for the School Levy,”

“Labels,” and “The News from Iraq” by Sara Holbrook.

Reprinted by permission of the Author.

Poems: “Ducks,” “Ascent,” and “Stingray” by Michael

Salinger. Reprinted by permission of the Author.

“Noel” by Michael Plemmons. Copyright © 1985 by

Michael Plemmons. First appeared in the North American

Review. Reprinted by permission of the Author.

“The Sweet Perfume of Good-bye” by M. E. Kerr from

Visions: Nineteen Short Stories by Outstanding Writers for

Young Adults, edited by Donald R. Gallo. Copyright ©

1987 by Bantam Doubleday Dell. Reprinted by permission

of the Author.

“Rose” from The Torturer’s Apprentice by John Biguenet.

Copyright © 2000 by John Biguenet. Reprinted by permis-

sion of HarperCollins Publishers.

“Deportation at Breakfast” by Larry Fondation as appeared

in Flash Fiction: 72 Very Short Stories, edited by James

Thomas, Denise Thomas, and Tom Hazuka. Copyright ©

1992 by W. W. Norton. Reprinted by permission of the

Author.

“Chimpanzees of Wyoming” from Western Electric by Don

Zancanella. Copyright © 1996 by Don Zancanella. Pub-

lished by University of Iowa Press. Reprinted by permis-

sion of the Publisher.

“Forwarding Order Expired” by John M. Daniel. Reprinted

by permission of the Author.

“Fight #3,” “We? #5,” and “Mother #1” from And Yet They

Were Happy by Helen Phillips. Leapfrog Press, Leaplit,

2011. Reprinted by permission of the Publisher.

“The Father” from Will You Be Quiet, Please? by Raymond

Carver. Copyright © 1992 by Raymond Carver. Reprinted

by permission of International Creative Management, Inc.

“This Is How I Remember It” by Elizabeth Kemper French.

Reprinted by permission of the Author.

“Little Things Are Big” by Jesus Colon from Choosing to

Participate. Copyright © 2009 by Facing History and

Ourselves National Foundation. Reprinted by permission

of International Publishers Company, Inc., New York, and

Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation.

“The Container” from Minor Robberies: 145 Stories in a

Small Box by Deb Olin Unferth. Copyright © 2007 by Deb

Olin Unferth. Published by McSweeney’s, San Francisco.

Reprinted by permission of the Author.

“Little Brother

™” by Bruce Holland Rogers as appeared

in Strange Horizons. www.strangehorizons.com,

October 2000. Reprinted by permission of the Author.

www.shortshortshort.com.

“Three Soldiers” by Bruce Holland Rogers as appeared in

Flash Fiction Forward: 80 Very Short Stories, edited by

James Thomas and Robert Shapard. Copyright © 2006 by

W. W. Norton. Reprinted by permission of the Author.

www.shortshortshort.com.

“The Wallet” by Andrew McCuaig. Originally appeared in

Beloit Fiction Journal (2001), Vol. 17, p. 130. Reprinted by

permission of the Author.

“Kennedy in the Barrio” by Judith Ortiz Cofer is reprinted

with permission from the publisher of “Year of Our Revo-

lution” by Tomas Rivera (© 1998 Arte Público Press—

University of Houston).

VII

Credits continued from page ii:

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page vii

“Nikki-Rosa” from Black Feeling, Black Talk, Black Judge-

ment by Nikki Giovanni. Copyright © 1972 by Nikki Gio-

vanni. Reprinted by permission of the Author.

“Mother Disapproved of Him” by Rita Mae Brown from

3 Minutes or Less: Life Lessons from America’s Greatest

Writers. Copyright © 2000 by PEN/Faulkner Foundation.

Reprinted by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

“Sure, You Can Ask Me a Personal Question” by Diane

Burns from Aloud! Voices from the Nuyorican Poets Café.

Copyright © 1994 by Michael Algarin and Bob Holman.

Published by Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Reprinted

by permission of the Copyright Holder.

“Dozens of Roses: A Story for Voices” by Virginia Euwer

Wolff. Copyright © 1997 by Virginia Euwer Wolff. First

appeared in From One Experience to Another published

by Tom Doherty Associates. Reprinted by permission of

Curtis Brown, Ltd.

“My Father,” copyright © 2000 by Pat Conroy. Originally

appeared in 3 Minutes or Less: Life Lessons from America’s

Greatest Writers, edited by PEN/Faulkner Foundation.

Reprinted by permission of Marly Rusoff Literary Agency

for the Author.

“Heroes” by Tim O’Brien from 3 Minutes or Less: Life Les-

sons from America’s Greatest Writers. Copyright © 2000 by

PEN/Faulkner Foundation. Reprinted by permission of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

PHOTO CREDITS

Frederic Remington (1861 –1909), American, The Advance-

Guard, or The Military Sacrifice (The Ambush), 1890. Oil

on canvas, 87.3 × 123.1 cm (34

⅜ × 48 ½ in.). George F.

Harding Collection, 1982.802, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Julius von Leypold (1806–1874), Wanderer in the Storm.

Germany, 1835. Oil on canvas, 16¾ × 22 ¼ in. (42.5 × 56.5

cm). Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund,

2008 (2008.7). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

York, NY, USA.

Willard Midgette (1937–1978), “Sitting Bull Returns” at the

Drive-In, 1976. Oil on canvas, 108 ¼ × 134

⅛ in. Gift of

Donald B. Anderson. Smithsonian American Art Museum,

Washington, DC, USA.

Stevan Dohanos (1907–1994), Mining Village (Study for

mural, Huntington, West Virginia, forestry service build-

ing), 1937. Tempera on fiberboard. Sheet: 15

⅞ ×17 in.

(40.3 × 43.2 cm); Image: 12

⅜ × 14 in. (31.3 × 35.7 cm).

Transfer from the General Services Administration

(1974.28.308). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Wash-

ington, DC, USA.

James Henry Moser (1854–1913), Untitled (Two Children

Playing Checkers), n.d. Pastel on paper, frame: 21 × 17 in.

(53.3 × 43.2 cm). Bequest of Carolyn A. Clampitt in mem-

ory of the J. Wesley Clampitt, Jr. Family (2010.10). Smith-

sonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

VIII

Credits, continued

TL_Fiction_Chapter FM_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:56 AM Page viii

WELCOME

GREETINGS, COLLEAGUES.

We are Smokey Daniels and Nancy Steineke, join-

ing you again with a new resource that we hope you’ll find useful.

Over the past several years, we have worked with students and teachers in

twenty-two states, conducting reading workshops and giving demonstration

lessons in middle and high school classrooms. Nancy’s day job is at Victor J.

Andrew High School in suburban Chicago, where she has taught language arts

(and once upon a time, home economics, but that’s another story) for thirty-

five years. Since Smokey no longer has a classroom of his own, he now logs fre-

quent-flier miles as a cross-country guest teacher, including stints at schools in

Chicago, Appalachia, Arkansas, New York, Texas, New Mexico, Wisconsin, and

Hawaii (someone has to do it), along with writing books and leading workshops.

In 2011 we published Texts and Lessons for Content-Area Reading, which

included collaborative comprehension lessons and kid-friendly nonfiction arti-

cles from a crazy array of sources (Rolling Stone, the Discovery Channel, the New

York Times, etc). Since that book came out, English language arts teachers have

been requesting a companion volume that uses literature instead of informational

text to teach deep comprehension and collaborative discussion. They wanted a

book that’s just for us ELA folks, not those greedy history and science teachers

served by the previous book. Our first love is literature, too. Who are we to refuse?

So here’s the product of our two-year search for the best, freshest, and

most engaging short literature for young people—and a collection of new, step-

by-step lessons that guide kids into, through, and beyond these texts. As with

the nonfiction edition, these lessons use engaging short selections to teach

close reading and deep comprehension through collaborative conversation

and lively debate. And every lesson in the book is correlated with the Common

Core Anchor Standards for Reading—as well as many standards for Speaking

and Listening, Language, and Writing.

Meeting and Exceeding the Common Core

State Standards

The experiences provided by our upcoming thirty-seven lessons closely parallel

the readings and tasks recommended by the Common Core State Standards

(CCSS) as well as the performances required in tests from the Partnership for

Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) and Smarter Balanced

Assessment Consortium (SBAC). The main difference is that our lessons put stu-

dent curiosity and engagement first. The experiences are highly active and stu-

dent centered, unlike so many of the CCSS prep materials being developed

around the country.

1

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

1

CHAPTER 1 / Welcome

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 1

2

CHAPTER 1 / Welcome

In recent years, the Common Core Standards have had a dramatic and some-

times unsettling impact on schools and teachers. We have plenty to say about the

challenges of the Core, but luckily for you, we are not going to do it here. This

book is about addressing the standards, not critiquing them. Smokey and our col-

leagues Steve Zemelman and Arthur Hyde recently released the fourth edition of

Best Practice: Bringing Standards to Life in America’s Classrooms (Heinemann

2012). That book offers an extended and balanced treatment of the CCSS—and

the many other standards documents and research studies that, together, pro-

vide a full vision of what excellent teaching and learning look like today.

For now, we’ll just show how this resource can help you engage your kids

and meet the CCSS for the English Language Arts, and in particular the Reading

Standards for Literature 6–12. To begin with, here are the anchors:

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading

KEY IDEAS AND DETAILS

1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make

logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writ-

ing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

2. Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their

development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

3. Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and

interact over the course of a text.

CRAFT AND STRUCTURE

4. Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including

determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and

analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

5. Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences,

paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter,

scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

6. Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style

of a text.

INTEGRATION OF KNOWLEDGE AND IDEAS

7. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and

media, including visually and quantitatively as well as in words.

8. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text,

including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and

sufficiency of the evidence.

9. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics

in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the

authors take.

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 2

3

CHAPTER 1 / Welcome

RANGE OF READING AND LEVEL OF TEXT COMPLEXITY

10. Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts

independently and proficiently.

(www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf)

When you think about this list, you realize that any good reading lesson

should incorporate all of these goals. Why would we ever design a lesson in

which kids didn’t take all text details into account, pay attention to the author’s

craft, build knowledge, and gain proficiency with challenging materials? Stu-

dents deserve it all. So every lesson in this book helps students gain practice

with most or all of the reading anchor standards.

While our main aim in this book is to enhance the reading of literature, we

also address other Common Core Standards in Speaking and Listening, Lan-

guage, and Writing, and these correlations are prominently noted. For example,

every lesson includes both small-group and whole-class discussion, as explicitly

called for in the Speaking and Listening Standards. And, since all sixty-five of

the reading selections reproduced here model excellence in language use, the

lessons also help students meet key Language Standards. And finally, most les-

sons require some kind of student writing or note taking. While the written

assignments are mostly brief and informal, each one helps to build the fluency,

skills, and process knowledge students need to meet the Writing Standards.

Prominent sidebars will help you see which Common Core Standards and

skills are receiving special focus and attention all the way through the book.

Then, in the appendix, we offer a chart that helps you correlate the lessons with

all relevant standards.

About the Readings: What’s Fresh in the Market?

Sometimes it seems as though the same fifty short stories and the same fifteen

poems are anthologized over and over. Partly, that’s because the major textbook

companies want to offer students time-tested readings from celebrated authors.

But there are plenty of other works of great literature out there, if you know

where to look for something fresh.

So where do we look? Both of us are inveterate and passionate collectors of

short-short fiction and short poems, in both their tree-based and digital forms.

If you looked at our voluminous email correspondence, or eavesdropped on our

weekly Saturday morning phone calls, you’d mainly hear us trading and reading

aloud great short pieces.

We are also inveterate and passionate teachers of reading comprehension,

thinking, and discussion strategies. That means we need a constant supply of

short texts to use in quick, lively, in-class lessons. When we introduce our stu-

dents to almost any literary idea or device, it’s only natural to pull out a short lit-

erature piece from our collections. We came to call these texts “one-page

wonders” (OPW in shorthand) because we shopped for kid-friendly reading

selections that could be photocopied on one or two pages.

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 3

The reading selections we’ve collected here cover the genres of short stories,

poems, drama, and novels, with some essays and accompanying nonfiction

pieces appearing in the text sets (see Chapter 10). When choosing OPWs, we

favor selections that:

• are engaging, complex, and mostly contemporary

• feature newer, up-and-coming writers (or, if written by famous authors,

are not widely anthologized)

• are fresh to us teachers, too, so we can have the joy of discovery right

along with our kids

• have sufficient sensory detail and rich language to conjure up vivid

images of places and characters

• have enough depth and craft to reward second, closer readings

• address themes that can stimulate lively discussion and debate

among students

• are short enough to be read during class, so that a whole lesson can

be completed in one period or less

• allow photocopying, so kids can annotate their own copies

• help students practice key comprehension and thinking strategies

• can be extended into more days, or tied into broader literature units

We want to be especially clear about text complexity, a key focus of the Com-

mon Core Standards. A few of our chosen readings are intentionally easy to enter,

enjoy, and talk about. And why not? As the standards say, “Students need opportu-

nities to stretch their reading abilities but also to experience the satisfaction and

pleasure of easy, fluent reading, both of which the Standards allow for” (2010, p. 39).

But our main job, year in and year out, is to lead our students up a ladder of

challenge, building their stamina and pushing them along to literature that

requires more intentional thinking. But along that ladder, it’s also our duty to

provide just the right amount and type of support to keep kids progressing.

Every class period is not a high-stakes test; it is one more step upward

toward college and career readiness. So, even as we respect the CCSS focus on

complex text, we also think carefully about what makes that text accessible to

young readers along that upward path of their growth. Here are the considera-

tions we keep in mind:

FACTORS THAT MAKE COMPLEX TEXT MORE ACCESSIBLE

• The text is shorter rather than longer.

• The reader has chosen the text, versus it being assigned.

• The reader has relevant background knowledge.

• The topic has personal interest or importance.

• The text evokes curiosity, surprise, or puzzlement.

• The text has high coherence, meaning that it explains itself (e.g., “John

Langdon, a farmer and signer of the Constitution . . .”).

4

CHAPTER 1 / Welcome

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 4

• The teacher evokes and builds the reader’s background knowledge.

• The teacher teaches specific strategies for monitoring comprehension,

visualizing, inferring, connecting to background knowledge, question-

ing, determining importance, and synthesizing.

• Readers can mark, write, or draw on text as they read.

• Readers are encouraged to talk about the text during and after reading.

• Readers can hear text read aloud by the teacher, by a classmate, or in a

small group.

• Readers have experience writing in the same genre.

Still, make no mistake about it: 90 percent of the pieces in this collection

are plenty complex. That’s because they are full-strength adult literature, which

we think middle and high school students should be engaging with regularly.

So we didn’t worry so much about Lexiles; instead, we picked selections that

grown-up, lifelong readers have paid to read. Trust us, there are plenty of pieces

here that give us English majors a run for our interpretive money, but are still

intriguing enough to keep teen readers digging and thinking.

Which brings us back to the question in our subhead, What’s fresh in the

market? You hear that expression a lot on those TV cooking shows when the

cameras follow a Famous Chef through the farmer’s market, right? She is looking

for the dewiest veggies, the most exotic meats, the strangest grains (freekeh, seri-

ously? kamut berries, really?), the revelatory ethnic treats. Great cooks seek the

latest, the newest, the weirdest. They want challenge. They want to create a dish

they’ve never cooked before. They want to work on the edge, take some risks,

and dazzle their diners.

If we literature teachers are chefs too, then we really need some fresh pro-

duce. To begin with, you just get tired of teaching To Kill a Mockingbird for the

twenty-third time (unless you’re Nancy). More importantly, when we teach a

novel or story to our students, they too often see us “read” texts we have read

many times before, thought about, talked about, maybe even written about. We

know it cold from all our previous encounters.

But this is not the same job we ask kids to do when they come in the class-

room each day. We place unfamiliar text in front of them and ask them to read it

“cold.” They almost never see us encountering unknown text, working to build

meaning the first time through. Well, if reading unfamiliar text is the students’

actual task, then we teachers better be demonstrating that job, early and often.

That means we need new texts to refresh and challenge ourselves.

Now, these sixty-five little jewels won’t be our favorite literary clips forever;

we’re always finding and adding new ones to the repertoire—and you should,

too. As you work with these pieces, you’ll start to internalize what makes a one-

page wonder, and start collecting your own. Hope you get as geeky about find-

ing them as we are.

So, shall we move on to the nuts and bolts of the lessons?

5

CHAPTER 1 / Welcome

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 5

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

6

Coming right up, Chapters 3 through 9 present thirty-seven strategy lessons for

improving students’ literary comprehension and discussion, using very short

texts. In Chapter 10, we offer eight text set lessons, thematically connected

assortments of pieces designed to be studied, compared, and debated together.

Then, in Chapter 11, we bring forward three commonly taught whole-class nov-

els and show how you can use selected lessons from this book to teach those

works—and countless others—in a highly interactive, engaging way. And finally,

in Chapter 12, we explain how to grow your own inventory of special texts for

teaching literary thinking. Here’s the rundown.

Chapters 3–9: Strategy Lessons

The strategy lessons are each accompanied by at least one “one-page wonder”—

an enticing poem, short-short story, essay, or image that engages students in

close reading, thinking, and discussion. We selected these pieces with literary

quality and student engagement foremost in our minds. They cover a wide

range of genres and themes; only a few are abridged. The lessons accompanying

these readings offer specific suggestions and language you can use to teach

them. They are written as generally as possible, so you can use (and reuse) the

steps and language with any compatible text you choose. And the strategy les-

sons are quick: they are designed to be completed within ten to fifty minutes.

We have grouped the lessons into seven families based on their thinking

focus as well as their standards connections.

Sharing Literature Aloud

Smart-Reader Strategies

Lively Discussions

Closer Readings

Up and Thinking

Literary Arguments

Coping with Complex and Classic Texts

The strategy lessons appear in what we’d call a “mild sequential order.” For

example, kids can’t do arguing both sides unless they first know how to pair

share with a classmate. Very generally, the lessons become more complex and

socially demanding as they unfold. But, that being said, use them in whatever

order you like; so far, no fatalities have been reported due to reordering. You

can also mix and match—any lesson with any reading selection, ours or yours.

If a piece looks too easy or hard for your kids, don’t give up on the lesson—find

an alternative text elsewhere in the book or in your own collection, and carry

2

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 6

on. And remember, always study any potential lesson text carefully to be sure it

is appropriate for your students and the community where you would like to

continue teaching.

Chapter 10: Text Set Lessons

The text sets follow a similar lesson format, but each one offers multiple coor-

dinated reading selections. Now students can range though two to five texts rep-

resenting different genres and authors, each of them taking a different angle on

a common topic or literary theme. This formula includes nonfiction selections

and various media in the mix, much as PARCC and Smarter Balanced assess-

ments do. Among our themes:

Memory

Citizenship

Life Stories

Mothers and Daughters

Narcissism

Labels

Abuse

Soldiers and Heroes

Text set lessons about these rich topics offer multiple points of entry for

different students, and provide for a deep and sustained engagement in reading

and thinking. They can easily lead to multiday units in which students do their

own research to shed further light on the theme.

The suggested sequence of activities for a text set is built from strategy les-

sons in the first part of the book. Therefore, the instructions for text sets are

more compact, since the necessary lesson steps are given in earlier chapters.

Don’t worry, we’ll clearly signal where you should look for each lesson step.

Chapter 11: Keeping Kids at the Center

of Whole-Class Novels

Whole-class novels are still a big part of the English language arts curriculum

in most middle and high schools (thank goodness). But now teachers are won-

dering: How can I teach these great books in a way that’s harmonious with the

Common Core Standards? How do I ensure my students are grasping all impor-

tant details, noticing the author’s craft and structure, improving their academic

vocabularies, and always stepping up their thinking skills? All while still being

deeply engaged with the story and with each other?

We looked up the most commonly taught novels in middle and high school,

and three of the top titles were:

The Giver, by Lois Lowry

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald

7

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 7

8

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

Literature Selection:

Each lesson is accompanied by a

short piece of fiction or poetry,

a historic image, or an excerpt

from a longer work. For most

lessons, you may copy and

distribute the pieces to students.

(For four selections, the authors

were unable to grant classroom

copying rights, and we indicate this

on the footers for those texts.) Kids

must be able to write and mark

directly on the page, so

make copies

for everyone

—not just one set that

gets passed from class to class. Also

keep in mind that you can substitute

your own selection and adapt our

language to teach—or revisit—

these skills.

Title: Names the teaching strategy.

Introduction: This brief introductory

note gives background on the strategy,

structure, or text being used, and

explains its value for students.

Steps & Teaching Language: This is

the core of the lesson, where all the

activities and teacher instructions are

spelled out in sequence and in detail.

Text that appears in regular typeface

indicates our suggestions for the

teacher. Text in

italic

is suggested

teaching language that you can try on

and use. If you substitute your own

selection, check to see where the

language might need to be adapted.

Time: Tells the expected length of the

lesson. Most strategy lessons range

from 10 to 50 minutes, averaging 30.

Each text set lesson fills at least one 50-

minute class period—and we give you

steps and language to dig deeper over

several additional periods.

Grouping Sequence: Tells how lesson

shifts among pairs, small-group, and

whole-class configurations.

Used in Text Sets: Lists the text sets in

Chapter 10 that use the lessons.

21

May be photocopied for classroom use. Texts and Lessons for Teaching Literature by Harvey “Smokey’ Daniels and Nancy Steineke,

© 2013 (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann). Reprinted with permission.

Choices Made

Jim O’Loughlin

Part 1

Later, he would be able to consider all that he had left behind and never saw

again: the wedding album, the birth certificates, the kids’ favorite toys, even

the laptop. In the moment though, with the storm surging and blow back peel-

ing off the roof like masking tape, he only had time to grab what he could on

the way out.

Part 2

Still, even as he ran to the car, dripping sweat and bleeding from the gash in his

forehead, with the river already up to the wheel wells, he realized that the

choices he had just made said something about who he was. In his arms, he

held a phone book, the cantaloupe that had just turned ripe, and a gallon of

milk. And he had made sure to lock the front door.

SHARING LITERATURE ALOUD

Wise classroom practices—and the Common Core Standards—recognize the

importance of both teachers and students reading short literature selections aloud, and

paying close attention to the language, the ideas, and their own thinking as they do so.

C

HAPTER

3 / Sharing Literature Aloud

18

Steps &

u

Teaching

Language

TEXT

u

“Choices Made,”

by Jim O’Loughlin

TIME

u

10 Minutes

GROUPING SEQUENCE

u

Pairs,

whole class

USED IN TEXT SETS

u

3, 8

LESSON 3.1

Pair Share

This fifty-five-word story embodies a classic conversation starter: if you had to

suddenly flee your home, what three things would you take?

Well, it does happen. Every August, hurricane season begins in earnest.

People who live near the Atlantic coast must face the weather predictions with a

combination of dread, fear, and distrust. As we all know, for every prediction

that is dead-on, it seems like the previous ninety-nine—or more—have fizzled.

In the Midwest, we don’t have hurricanes; we have tornadoes, mostly tornado

watches and warnings that seldom become tornadoes. But when those storms

do make a direct hit, it’s often with little or no advance notice—especially if it’s

the middle of the night and people are sleeping. In the rest of the country,

depending on where you live and the season, you might be worrying about

floods, mudslides, brush/forest fires, or earthquakes. So, unlike the unwary

character in this story, be prepared!

PREPARATION

Copy the two-paragraph story and cut it in half. Good news: if you have a class

of thirty, you’ll only need to make fifteen copies! Be sure to put all the begin-

nings in one pile and the endings in another.

STEP 1

Organize pairs. Whenever kids will be working in pairs, they need to

know who their partner is beforehand, and they need to move into a

good conversation position—face to face, eye to eye, knee to knee

(probably not cheek to cheek). This setup encourages the use of

“indoor voices” and prevents noisy, time-wasting shuffling around mid-

lesson. For pairs, we like to have the kids simply push their desks

together or sit directly across a table from each other. In this lesson, sit-

ting side by side works best because both students will be reading from

the same page.

3

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 8

9

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

Common Core Standards

Supported: Lists CCSS

skills and principles

addressed in the lesson.

If you are using a basal or anthology, it probably tells you little or nothing about

how to set up successful partner or small-group work in your class. (You may

find some notes about social skills in the teacher’s edition). If you skipped our

Chapter 2, check it out: there’s some helpful information about training kids for

small-group work back on pages 10–13. Making these crucial advance moves,

such as setting up partners first and making sure they are positioned to commu-

nicate, makes a huge difference with our lessons—or the ones in your textbook.

Still have kids who don’t want to work with each other? Tell them that your stan-

dard is that “everybody works with everybody in here.” Then form partners daily,

by random drawing, so the pairing is not about you—and so that everyone

eventually does work with everyone else. Acquaintance builds friendliness.

20

C

HAPTER

3 / Sharing Literature Aloud

Shoptalk

u

19

Lesson 3.1 / Pair Share

STEP 2

Turn and talk. Pose the question that we previewed earlier: If you had

to escape from your house with only three things (assuming your family

and pets are OK), what would you take? Turn to your partner and share

your answers. Don’t forget to explain why these items are important to

you. What do they symbolize or represent?

STEP 3

Introduce and pass out the story. Each pair receives two hand-

outs, the beginning and the end of the story, face down. OK, first figure

out which of you two has the earliest birthday in the year. Got it? OK, the

person with the earliest birthday gets the first half of the story, and the

other gets the ending. As I pass this story out to you, I want you to keep

them face down for the time being. No peeking!

STEP 4

Give instructions. Early birthdays, ready? When I say go, turn your

paper over and begin reading aloud. Make sure you put the story in the

middle so that your partner can follow along. Once you finish reading,

stop and talk. Share your reactions, talk about what’s going on and why

the character chose not to take those items. Be sure that both you and

your partner contribute and that you actively challenge each other to go

into detail and really explain your thoughts.

When you are finished discussing the first half, the late birthdays should

turn their sheet over, put it between you, and then read aloud as your

partner follows along. After reading, have another discussion following

the same guidelines. Except this time, you need to talk about what the

character did take with him.

STEP 5

Concluding pairs discussion. I see that most of you have finished.

Before we share in a large group, I want you to recall the items you would

have taken in an emergency and compare yourselves to the story charac-

ter. What did you have in common? What things were different?

STEP 6

Share with the whole class. How did you explain what this charac-

ter actually took versus what he might have taken when he thought about

it later? What might these items symbolize? How did your “emergency

items” compare with the character’s choices?

Don’t prolong the sharing. Just get a few quick responses to each of the

questions. The important conversational work took place as the pairs

discussed together.

Even simpler: While we usually complicate things in these variations, this les-

son actually has some fun wrinkles already. So we’ll just mention a simpler ver-

sion for this one. Eliminate the cutting in half and just let partners gobble the

story in one gulp (thirty seconds?), then get into that turn-and-talk.

COMMON CORE

STANDARDS SUPPORTED

• Read closely to determine

what the text says explicitly

and to make logical

inferences from it; cite

specific textual evidence

when writing or speaking to

support conclusions drawn

from the text.

(CCRA.R.1)

• Interpret words and phrases

as they are used in a text,

including figurative

meanings.

(CCRA.R.4)

• Assess how point of view

shapes the content and style

of a text.

(CCRA.R.6)

• Participate effectively in a

range of conversations and

collaborations.

(CCRA.SL.1)

t

Variation

Variations: In this section you’ll

find specific ways you can vary,

modify, or extend the lesson.

Some of these variations can

extend the lesson into the

following class period.

Shoptalk: Here we offer

comments about when to use

the lesson, how to coordinate

it with your textbook (if you

have one), and other teaching

topics we’d like to share.

Web Support: All the

charts, lists, or forms

that need to be

projected for any lesson are on our

website, www.heinemann.com

/textsandlessonsliterature.

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:28 PM Page 9

So we chose these three books as “exemplar texts” in showing how you can

use our lessons to teach a novel. Basically, you’ll see us stringing together a log-

ical sequence of strategy lessons from Chapters 3 through 9, with bits of con-

nective tissue added where needed. Of course, the point of this chapter is not

these three specific books, but the process by which you can build an engaged,

interactive, and standards-friendly approach to any novel.

Chapter 12: Extending the Texts and Lessons

While this book provides sixty-five great reading selections, there are about 180

days in most of our school years! Hmm, doing the arithmetic, you could run out

of text around New Year’s and be hungry for more. In this short chapter, we give

away all of our secrets for finding more short, kid-friendly literature selections.

We offer bibliographies for the short-short story genre, for poetry, and for

images and artworks. We also explain how you can write your own one-page

wonders for kids. Really, you can.

Working in Groups

These lessons are all highly interactive and collaborative, because that’s what

part of what engages kids and gets them thinking. The Common Core Standards

also push pretty hard for us to get students working with each other. The Speak-

ing and Listening anchor standards are quite general, and most of our lessons

address many or all anchors.

But just for fun, let’s drill down into the more specific Speaking and Listen-

ing Standards for grades 9–10 as an example. Students should:

1. Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions

(one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades

9–10 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their

own clearly and persuasively.

a. Come to discussions prepared, having read and researched material

under study; explicitly draw on that preparation by referring to evi-

dence from texts and other research on the topic or issue to stimulate a

thoughtful, well-reasoned exchange of ideas.

b. Work with peers to set rules for collegial discussions and decision-making

(e.g., informal consensus, taking votes on key issues, presentation of alter-

nate views), clear goals and deadlines, and individual roles as needed.

c. Propel conversations by posing and responding to questions that relate

the current discussion to broader themes or larger ideas; actively incor-

porate others into the discussion; and clarify, verify, or challenge ideas

and conclusions.

d. Respond thoughtfully to diverse perspectives, summarize points of

agreement and disagreement, and, when warranted, qualify or justify

their own views and understanding and make new connections in light

of the evidence and reasoning presented.

In every one of our lessons, students are interacting in just these ways.

10

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

When we started teaching,

there was one tool for display-

ing documents to a whole

class: the overhead projector.

Today, there are a million ways

of projecting material: docu-

ment cameras, smart boards,

whiteboards, iPads, you name

it. Many of our lessons use

instructions or images or short

chunks of text, which, though

they are included in the book,

work much better if projected

for the class. So we have

placed these on our website

and provided additional links

that were active at the time of

publication (www.heinemann

.com/textsandlessonslitera

ture).

PROJECTION

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 10

If you worry that your students might not be ready to collaborate as the CCSS

requires, you are not alone. For a variety of reasons, teenage students may find it

hard to manifest the focus, friendliness, and support that these face-to-face meet-

ings require. So we have designed our lessons to enhance on-task conversations.

• The readings are interesting.

• The instructions are explicit.

• Every kid-kid meeting is highly structured.

• Every lesson follows a “socially incremental” design. Kids typically

begin working with just one other person (more controlled than

starting in groups of four or five).

• Once collaboration is established, kids can move from pairs to

small groups.

• Finally (and always) lessons finish in a whole-class discussion,

orchestrated by the teacher.

As you can already see, we rely extensively on pairs or partners in these

lessons—and in all our work with young people. When students are meeting

with just one other learner, they experience maximum “positive social pressure.”

That means both persons totally need each other to complete the task. There’s

no chance to slough off and hope other group members will pick up the slack.

There are no other members—you two are it! So you have to pay attention, lis-

ten carefully, speak up, and take on your share of the work. With pairs, there

tend to be fewer distractions, sidetracks, and disputes of the kind we sometimes

have to manage in larger groups.

11

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

These lessons are generally pretty low-tech. Mostly, you just photocopy the articles and

prepare kids to have meaningful conversations. But there are a few supplies we like to

have around:

• Post-it notes of various sizes

• Index cards, 3x5-inch and 4x6-inch varieties

• Large chart paper or newsprint and tape

• Fat and skinny markers in assorted colors

• Clipboards: When kids are working with short selections, they may be moving around

the room, sitting on the floor, meeting in various groups. They’ll need to bring a hard

writing surface. A weighty textbook works, but feather-light clipboards were made to

be portable desks.

• A projector that allows you to show the lesson instructions we’ve parked for you on our

website, as well as images, work samples, and web pages related to the lessons.

• In our ideal classroom, kids would also have individual tablet computers, on which we

can preload great text and images, and then kids can annotate and write about them,

joining in digital conversations in live or online settings. However, every student must

have the exact same device and be able to use it as fluently as paper and pencil, or the

technology can actually distract from the brisk pace of these lessons.

MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 11

In almost every lesson, you’ll have to decide how to form pairs (or groups

of three or four), and there is a lot to think about. You already know what hap-

pens when you let friends work with each other; lots of kids get left out, while

the friend partners have plenty to talk about, other than your lesson. Instead,

keep mixing kids up, arranging different partners for every activity, every day.

This is part of your community building. Everyone gets to know everyone. No

one gets to say, “I won’t work with him.” Let’s learn from kindergarten: write each

kid’s name on a popsicle stick and keep them in a coffee mug. When it’s time to

pick partners, students draw from the mug. This way, pairings are random; it’s

never about you personally forcing certain kids to work together. No arguments

and no groaning allowed. As the weeks unfold and kids’ collaboration skills are

honed in pair work, we feel more comfortable putting them in small groups dur-

ing our lessons. And later in the year, kids will have partners or groups that stay

together over many days, as in book clubs, writing circles, and inquiry circles.

Maybe you have a class that needs even more support to succeed at stu-

dent-led discussion. In such situations, the key is to explicitly teach the social

skills kids need, before they head off into small groups. This is a topic we have

treated extensively in other books, and won’t re-spout our wisdom here. But for

those who want more information on explicit social skill lessons, we have

posted some links on the book’s website.

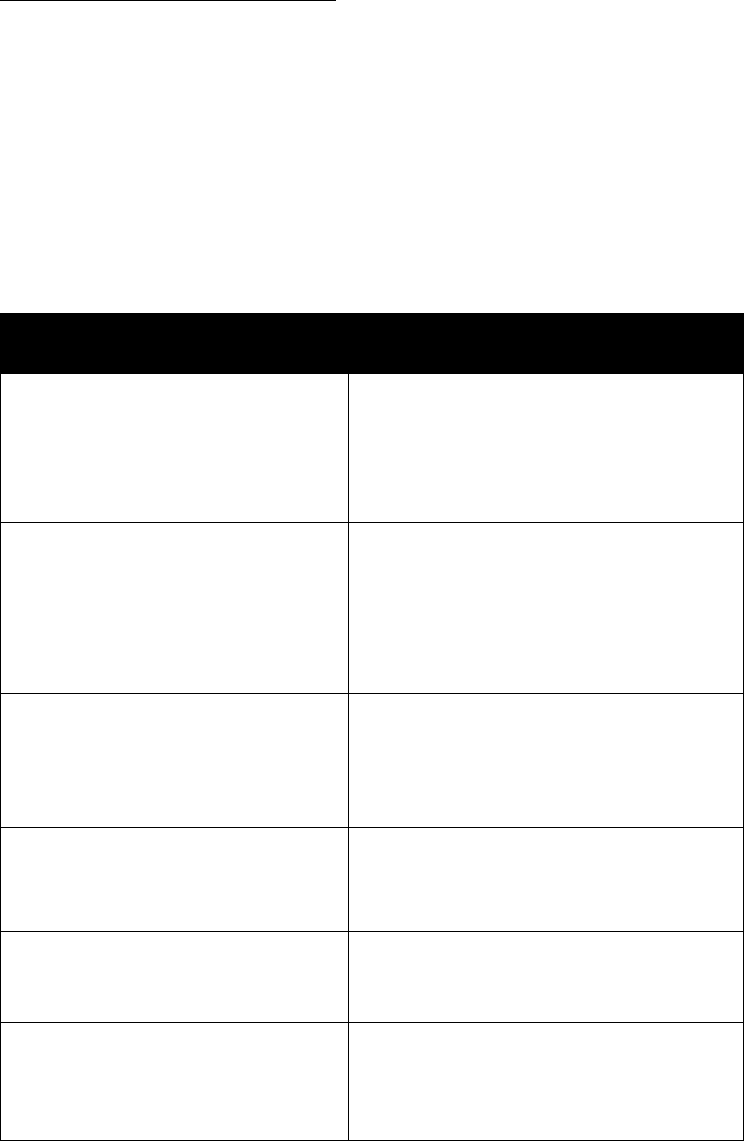

Below is a chart showing seven key collaboration strategies kids need to

develop, adapted from Smokey and Stephanie Harvey’s Comprehension and

Collaboration (2009). As you can see, the chart gives both positive and negative

examples of each skill. Maybe you will recognize some of your own students

there, hopefully not in the right-hand column.

12

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

STRATEGY EXAMPLES/ACTIONS SOUNDS LIKE DOESN’T SOUND LIKE

1. Be responsible

to the group

• Be prepared: work completed,

materials and notes in hand

• Bring interesting questions/ideas to

the discussion

• Fess up if unprepared

• Focus on the work and members

• Establish and live by your group’s

ground rules

• Settle issues within the group

“Does everyone have their

reading? Good, let’s get

going.”

“I’m sorry, guys, I didn’t get

the reading done.”

“OK, then today you’ll take

notes on our conversation.”

“What? There’s a meeting?”

“I left my stuff in my locker.”

“Teacher, Bobby keeps

distracting our group.”

2. Listen

actively

• Use names

• Make eye contact

• Nod, confirm, look interested

• Lean in, sit close together

• Summarize or paraphrase

“Joe, pull your chair up

closer.”

“Fran, I think I heard you

say . . . ”

“So you think . . . ”

“I’m not sitting by you.”

Huh?”

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 12

STRATEGY EXAMPLES/ACTIONS SOUNDS LIKE DOESN’T SOUND LIKE

13

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

4. Share the air

and encourage

others

• Take turns

• Be aware of who’s contributing,

and work to even out the airtime

• Monitor yourself for dominating or

shirking the conversation

• Invite others in

• Receive others’ ideas respectfully

• Use talking stick or poker chips

if needed

“What do you think,

Wendy?”

“I better finish my point and

let someone else talk.”

“That’s a cool idea, Tom.”

“Can you say more about

that, Chris?”

“Blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah . . . ”

“I pass.”

5. Prove your

point/support

your view

• Explain, give examples

• Refer to specific passages

• Read aloud important sections

• Dig deeper into the text, reread

important parts

“I think Jim treats Huck as a

son because . . . ”

“Right here on page 15 it

says that . . .”

“This book is dumb.”

“Why open the book?”

“Well, that’s my opinion

anyway.”

6. Disagree

agreeably

• Be tolerant of other’s ideas

• Speak up—offer a different

viewpoint and don’t be steamrolled

• Use neutral language: “I was thinking

of it this way”

• Celebrate and enjoy divergent

viewpoints

“Wow, I thought of

something totally different.”

“I can see your point, but

what about . . . ”

“I’m glad you brought that

up; I never would have seen

it that way.”

“You are so wrong!”

“What book are

you

reading?”

“No way!”

7. Reflect and

correct

• Identify specific behaviors that helped

or hurt the discussion

• Talk openly about problems

• Make plans to try out new strategies

at the next meeting and then review

their effectiveness

“What went well today and

where did we run into

problems?”

“OK, so what will we do

differently during our next

meeting?”

“Let’s write down our plan.”

“We rocked.”

“We sucked.”

“It was OK.”

3. Speak up

• Join in, speak often, be active

• Use a moderate voice level

• Connect your ideas with what others

just said

• Overcome your shyness

• Ask lead and follow-up questions

• Use your notes or annotations, or

drawings

“What you said just

reminded me of . . . ”

“What made you feel that

way?”

(silence)

Not using/looking at notes

when conversation lulls

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 13

This resource stands on its own, offering

immediately usable readings and lan-

guage for collaborative lessons in think-

ing about literature. But it was also

created to be used with several recent books by our

“family” of coauthors. Over the past ten years, our own

collaborative group has created a library of books

focused on building students’ knowledge and skill

through the direct teaching of learning strategies in the

context of challenging inquiry units, extensive peer col-

laboration, and practical, formative assessments.

Among these books are:

• Best Practice: Bringing Standards to Life

in America’s Classrooms, 4th edition

(Zemelman, Daniels, and Hyde 2012)

• Best Practice Video Companion (Zemelman

and Daniels 2012)

• Comprehension Going Forward (Daniels 2011)

• Texts and Lessons for Content-Area Reading

(Daniels and Steineke 2011)

• Assessment Live: 10 Real-Time Ways for Kids to

Show What They Know—and Meet the Standards

(Steineke 2009)

• Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles

in Action (Harvey and Daniels 2009)

• Mini-lessons for Literature Circles (Daniels and

Steineke 2006)

• Content-Area Writing: Every Teacher’s Guide

(Daniels, Zemelman, and Steineke 2005)

• Subjects Matter: Every Teacher’s Guide to

Content-Area Reading (Daniels and Zemelman

2004)

• Reading and Writing Together (Steineke 2003)

ALL IN THE FAMILY

14

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

These seven strategies are embedded over and over again in this book’s les-

sons. As you teach them, your kids will be getting plenty of practice and becom-

ing better partners and group members—and meeting the Speaking and

Listening Standards for the Common Core or your state.

How Proficient Readers Think

Here’s a question: How do effective, veteran readers think when they are reading

stories, poems, literary essays, or plays? What goes on in their minds? Exactly how

do they turn those little marks on the page into understanding and knowledge in

their brains—especially when the text is hard or old or boring? If there are some

effective patterns and strategies, we need to know what they are, so we can teach

them to the kids. Like ASAP.

Happily for us, some reliable and well-replicated research (Pearson and

Gallagher 1983; Pearson, Roehler, Dole, and Duffy 1992; Daniels 2011) give us a

very pretty clear picture of the key cognitive strategies in play. Powerful readers:

Monitor their comprehension Draw inferences

Connect to background knowledge Determine what’s important

Visualize and make sensory images Synthesize and summarize meaning

Ask questions of the text

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 14

15

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

Chapter 4 offers seven lessons, each dedicated to one of these cognitive

strategies, in the above order. But these seven core reading strategies are fully

incorporated throughout the book; kids will practice each one repeatedly as you

lead them through the readings, activities, and conversations.

Assessment

If you are going to devote ten minutes or twenty-five minutes or a whole class

period to one of these lessons, the question naturally arises: How do I grade

this? After all, in today’s schools, it seems like we have to assess, or at least assign

a grade to, almost any activity kids spend time on.

It is important to recognize that these lessons, by themselves, do not lead to

final public outcomes, such as polished essays or crafted speeches. They can

and often do serve as starting points for just such projects, which require extra

time and support for their completion. But as they stand, our lessons are more

like guided practice, opportunities for kids to read and write and talk to learn.

That requires an appropriate approach to assessment.

Participation Points

You can certainly give kids points or grades for effective participation in these

lessons. But if you start qualitatively grading every piece of kids’ work on activi-

ties like these, trying to defend the difference between a 78 and a 23, you’re going

to give up huge chunks of your own time marking, scoring, and justifying. Maybe

this is some of our old Chicago “tough love” creeping in, but for smaller everyday

assignments, we use binary grading: yes/no, on/off, all/nothing. We give 10 points

for full participation and 0 points for non-full participation. No 3s, no 7.5s. Ten or

zero, that’s it.

Our colleague Jim Vopat has brought some poetry to this kind of grading in

his book Writing Circles (2009). Jim calls this “good faith effort.” If a student

shows up prepared to work, having all the necessary materials (reading done,

notes ready), joins in the work with energy, and carries a fair share of the work—

that’s a “good faith effort” and earns full points. From a practical point of view,

this means we only need to keep track of the few kids who don’t put forth that

GFE, and remember to enter that zero in our gradebook later on.

Still, let’s be honest. Giving points is not assessment, it’s just grading. When

we want to get serious and really scrutinize kids’ thinking in these activities, we

have to take further steps.

Collect and Save Student Work

As kids do the activities in these forty-five lessons, they naturally create and leave

behind writings, lists, drawings, notes, and other tracks of their thinking. So why

pop a quiz? Instead, collect, study, and save the naturally occurring by-products

of kids’ learning. These authentic artifacts, this residue of thinking, are far more

meaningful than a disembodied “72” in your gradebook. The kids’ own creations

are also far more relevant in a parent conference or a principal evaluation than a

string of point totals in a gradebook.

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 15

16

OBSERVATION CHART

STUDENT NAME “GOOD FAITH” QUOTE THINKING SOCIAL SKILLS

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

May be photocopied for classroom use. Texts and Lessons for Teaching Literature by Harvey “Smokey” Daniels and Nancy Steineke, © 2013 (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann).

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 16

Observe Kids at Work

The form on page 16 is a tool we use when sitting with a group of kids, watching

them work on a lesson together. As you can see, this form incorporates Vopat’s

good faith idea and then goes much further. As we listen in on kids, we jot down

one memorable quote from each student and reflect on what kind of thinking

this comment or question represents; we also take notes on any conspicuous

use (or neglect) of the collaboration skills called for in the lesson.

Offer Meaningful Performance Opportunities

When the time comes to assign grades for kids’ work over long stretches of time

and big chunks of content, we traditionally make up a big test and add that

score to the points kids have earned along the way. Even as we do this, we qui-

etly recognize that this assessment system invites cramming, superficiality, and

the wholesale forgetting of content.

Instead, we like to devise authentic events at which kids share or perform

their learning for an engaged audience—and then we use a rubric that care-

fully defines a successful performance to derive each kid’s grade. This might

mean a polished essay published on the web, a series of tableaux performed

with a group, or a full-scale public debate or talk show enactment. Nancy has

written a whole book with ideas on this kind of performance process called

Assessment Live: 10 Real-Time Ways for Kids to Show What They Know—and

Meet the Standards (Heinemann 2009).

Have Fun

We’re serious about putting this “F-word” back into school. The two of us had a

blast searching out these amazing short texts and using them with kids around

the country. In those classrooms, everyone seemed to have a good time reading,

savoring, analyzing, debating, and even rereading these little literary gemstones.

Field-testing these lessons with kids has reminded us that “all adolescents want

to work hard and do well,” as the brilliant British educator Charity James once

wrote in her book Young Lives at Stake: The Education of Adolescents.

Or you can just call it “rigor without the mortis.”

Enjoy!

Smokey and Nancy

17

CHAPTER 2 / How to Use This Book

TL_Fiction_Chapter1-3_Layout 1 2/6/13 12:00 PM Page 17

TEXT

u

“We? #5” by Helen

Phillips

TIME

u

20 Minutes

GROUPING SEQUENCE

u

Whole

class, pairs, whole class

USED IN TEXT SET

u

8

LITERARY ARGUMENTS

The Common Core Standards want kids not just to persuade, but to argue. Interesting

choice of words. When you think about it, “persuasive” sounds pretty genteel, while

“argue” has a more aggressive connotation. The technical difference is that when we are

persuading, we only need to make our own case. But to argue, you also have to

acknowledge the other side’s position—and then crush it. These lessons reflect our belief

that to get good at this process, kids need lots of practice drawing on textual evidence to

develop an interpretation, and then testing it against others’ thinking.

LESSON 8.1

Take a Position

Remember the last episode of The Sopranos? You don’t? Then you might want to

take some time off and devote eighty-three hours to watching the complete

DVD collection. On the other hand, you can just keep reading and take our word

for what follows . . .

. . . at this point, Tony is pretty much the last man standing, since an earlier

mob war has wiped out his crew. To top it off, the feds have him cornered. Tony

waits in a diner, sitting in a booth while a suspicious-looking guy at the counter

is eyeing him. Who is this guy? Hit man? Mob celebrity stalker? Job applicant

who heard there were openings? We don’t know, but he’s sure making us nerv-

ous! The camera keeps switching between the front door, Tony, guy at the

counter. Anxiety mounts for the viewer, not so much for Tony. He seems pretty

happy; maybe his new meds are kicking in? Someone’s at the door. Oh no!

Whew, it’s only his wife, Carmella. The anxiety builds again, but then it’s just

A.J., his son. Finally Meadow walks in. Tony looks up. Screen goes blank and

stays that way for about ten seconds, and then the credits roll silently.

What the !*@#? That was it. Every viewer had to make up his/her own end-

ing based on the evidence they had gathered in the previous eighty-two

episodes. At the time the final installment aired, it created quite a buzz and

many viewers were angry. How could David Chase (writer, director, executive

producer) do this to them after they had invested half a lifetime watching that

show? The nerve of that guy! The next day, Chase stated, “I have no interest in

explaining, defending, reinterpreting, or adding to what is there.”

Yet months later Chase reneged on his “vow of silence” and claimed that

Tony didn’t die (reviving the chances of a future movie or Sopranos reunion

episode), telling the New York Daily News, “Why would we entertain people for

eight years only to give them the finger?” The ending was only an “artistic” deci-

sion. Personally we wish he had refused to give “the right answer,” but probably

8

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

169

Lesson 8.1 / Take a Position

TL_Fiction_Chapter 7_8_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:49 AM Page 169

he was tired of being pilloried in YouTube comments as obsessed viewers

watched and rewatched Tony’s last five minutes. Luckily, few authors face the

same degree of scrutiny about their endings.

How many times have you had students read a story or novel, get to the

end, and say, “That’s it? What happened?” But what we really want them to say is

“Cool. I’m glad the author thought I was smart enough to use the clues to make

my own meaning.” Here’s a chance to help your students make that transition.

PREPARATION

Make a copy of “We? #5” for each student. Practice reading the story aloud.

STEP 1

Define symbolism. A symbol is usually an object or graphic that rep-

resents more than its literal meaning; it also represents an idea or quality.

Take U.S. currency, paper money. The literal value of a twenty-dollar bill

is about the same as a single—same amount of ink, same paper, same

cost of printing—yet they symbolize different values. And then there are

all the different graphics on money that are more than just decoration:

the eagle, the unfinished pyramid with the eye floating above it. We could

probably spend the whole period just examining and deciphering the cur-

rency in our wallets, but we’re not. Instead we’re going to read a story.

STEP 2

Distribute the story and read aloud. To start off, I’m going to read

this story aloud and I want you follow along. As the story unfolds, I want

you to watch for something that seems to be working as a symbol. Any

questions on what I mean by symbol? Also, I want you to notice some-

thing else. In the last paragraph, the point of view jumps from third to

first person. What do you think that’s all about?

Read aloud. (If you think the title may be confusing to kids, you can tell

them that Phillips’ book has sets of stories that are numbered under the

same title. Hence “We? #5” is the fifth story about “We,” and the number

has no significance within the story.)

STEP 3

Highlight the story symbol. What object do you think is the sym-

bol? Students should readily recognize the blank die. What led you to

believe that’s a symbol? Students should mention the repetition.

STEP 4

Reread the story. Before we talk about what the symbol might mean,

I want you to reread the story once or twice (it’s short!), and decide for

yourself: What does that blank die represent? Once you think you know,

write down your idea and make sure that you’ve found lines in the story

to support your viewpoint.

STEP 5

Monitor and coach. Let kids work for five minutes or so, checking

in and coaching the ones who haven’t marked up their sheet and jotted

some symbolism notes.

170

CHAPTER 8 / Literary Arguments

COMMON CORE

STANDARDS SUPPORTED

• Read closely to determine

what the text says explicitly

and to make logical

inferences from it; cite

specific textual evidence

when writing or speaking to

support conclusions drawn

from the text.

(CCRA.R.1)

• Determine central ideas or

themes of a text and analyze

their development; summarize

the key supporting details and

ideas.

(CCRA.R.2)

• Analyze how and why ideas

develop over the course of a

text.

(CCRA.R.3)

• Interpret words and phrases

as they are used in a text,

including figurative

meanings.

(CCRA.R.4)

• Analyze the structure of

texts.

(CCRA.R.5)

• Assess how point of view

shapes the content and style

of a text.

(CCRA.R.6)

• Participate effectively in a

range of conversations and

collaborations.

(CCRA.SL.1)

Steps &

u

Teaching

Language

TL_Fiction_Chapter 7_8_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:49 AM Page 170

STEP 6

Pair share. Get together with your partner and discuss the blank die.

What might it symbolize? How do you know? Where’s the evidence? Listen

carefully to your partner. If you have different ideas, that’s OK. The impor-

tant thing is that you can logically defend your answer with text evidence.

STEP 7

Share out. OK, let’s hear some ideas. Anybody work with a partner who

had a completely different idea than you? Call on those students first and

have them explain their divergent opinions. Remember to always

require students to defend their opinions with text evidence. Interest-

ing. Anybody else have some other interpretations to share? I bet you’re

wondering what the right answer is, huh. I don’t know. It’s kind of like

that last episode of The Sopranos . . .

This activity lends itself to an extension into argumentative writing. Have stu-

dents use their notes to develop a strong essay defending their interpretation

of the central symbol of the story. Does the mysterious cube represent:

conquering depression

growing up

taking control of your life

breaking a bad habit

leaving your “baggage” behind

reaching out to other people

There are so many ways to look at this story and symbol. The kids will probably

surprise you with things that neither we, nor The Sopranos writing staff, would

ever think of.

171

Lesson 8.1 / Take a Position

t

Shoptalk

TL_Fiction_Chapter 7_8_Layout 1 2/6/13 11:49 AM Page 171

We? #5

Helen Phillips

Once there was a person whose sadness was so enormous she

knew it would kill her if she didn’t squeeze it into a cube one

centimeter by one centimeter by one centimeter. Diligently, she