A Review of Bear

Management in Michigan

October 2008

Table of Contents

Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1

Biology of Black Bears................................................................................................................... 1

Range and Distribution............................................................................................................... 1

Life History of Black Bears........................................................................................................ 2

Assessment of Bear Populations..................................................................................................... 6

Bear Population Indices.............................................................................................................. 7

Bear Population Estimators......................................................................................................... 8

Bear Population Model............................................................................................................... 9

Current Population Status and Range in Michigan..................................................................... 9

Harvest Management.................................................................................................................... 11

Legal Authority......................................................................................................................... 11

A Brief History of Bear Hunting in Michigan.......................................................................... 11

Current Management Areas...................................................................................................... 12

Quota System for Distributing Bear Hunting Licenses ............................................................ 12

Current Bear Hunting Periods................................................................................................... 13

Land Ownership........................................................................................................................ 13

Population Goals....................................................................................................................... 14

Management Strategies............................................................................................................. 15

Regulatory Process........................................................................................................................ 16

Establishment of Bear Harvest Objectives and License Quotas............................................... 16

Natural Resources Commission Process................................................................................... 17

Economic Impacts......................................................................................................................... 17

Bear-Human Interactions.............................................................................................................. 18

Biological and Social Carrying Capacity.................................................................................. 18

Bear-Human Encounters........................................................................................................... 19

Baiting and Supplemental Feeding........................................................................................... 20

Recreational Viewing................................................................................................................ 20

Orphaned Cubs.......................................................................................................................... 20

Bear-vehicle accidents.............................................................................................................. 21

Problem Bear Protocols ............................................................................................................ 21

Additional Bear Hunting Issues.................................................................................................... 21

Hunter Conflicts........................................................................................................................ 21

Standardization of Bear Hunting Regulations .......................................................................... 22

BMU Boundaries...................................................................................................................... 23

Baiting/Disease Issues .............................................................................................................. 24

Bear Participation/No Kill Tag License.................................................................................... 24

Guides....................................................................................................................................... 25

Literature Cited............................................................................................................................. 26

1

A Review of Bear Management in Michigan

Introduction

Black bears (Ursus americanus) are an important natural resource for the residents of Michigan,

and as trustee of this resource, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) uses a scientific

approach to management. Scientific management considers the status of bear populations, bear

ecology, and the social issues associated with bear-human interactions (both positive and

negative). Scientific information is obtained from research, in-state surveys, and published

literature. Scientific management also incorporates the concept of adaptive resource

management, an iterative process by which changes in management actions (e.g., hunting

regulations, or educational efforts) are evaluated to determine if these changes achieve

management goals. Management efforts over time are modified as new information is obtained,

new analyses are conducted, or factors that influence bear ecology change.

Michigan’s bear management program includes research to help understand bear ecology and

social acceptance capacity of Michigan’s residents. In addition, the DNR provides information

to the public about bears and technical assistance to landowners with unwelcome bear

encounters. Sport hunting has the capacity to influence abundance of black bears, provides

recreational opportunities, and is an important tool used to manage the size of Michigan’s bear

population.

The purpose of this review is to present general information on black bears and specific

information relevant to the situation in Michigan. It is hoped this review will provide

information to assist with the development of recommendations by the Bear Management

Consultation Team.

Biology of Black Bears

Range and Distribution

World-wide there are only eight species of bears. Three of those species occur in North

America, and the black bear is the only species found in Michigan. Black bears have a scattered

distribution throughout most of temperate and boreal North America from the edge of the Arctic

prairies in Alaska and Canada, south to central Mexico (Baker 1983). They are found in at least

35 states and all Canadian provinces. During European colonization and expansion, black bears

were largely extirpated from many of the Midwestern states, yet today populations are thriving in

the Upper Great Lakes and western states and remain in parts of most eastern and southeastern

states. In Michigan, black bears are common in the Upper Peninsula (UP) and areas of the

Northern Lower Peninsula (NLP). Bears are occasionally observed in the Southern Lower

Peninsula (SLP) and these observations have become more frequent in recent years.

2

Life History of Black Bears

Physical Characteristics

In the Upper Great Lakes Region, most black bears have black or extremely dark brown fur.

Other color variations including brown, cinnamon, grayish-blue, and blonde are found mostly in

western North America (Baker 1983). Color is generally uniform except for a brown muzzle and

occasional white blaze on the chest (Ternent 2005).

Average adult black bears stand less than three feet tall at the shoulder and are approximately

three to five feet in length. Males are typically larger than females. Adult female black bears

weigh approximately 90 to 300 pounds, and adult males weigh about 130 to 500 pounds. All

bears tend to gain weight in the fall and lose weight during the winter period of inactivity

(Ternent 2005). However, despite losing up to thirty percent of their fall body weight in the

winter, many bears emerge from dens in the spring in relatively good condition (Gerstell 1939,

Alt 1980).

Reproduction and Growth

Generally, female black bears are sexually mature at three to five years of age (Pelton 1992), yet

are known to breed at two years of age in the NLP (Etter et al. 2002). Sows from the NLP

typically bred earlier (2-3 years of age) and had above average litter size (2.6 cubs per sow)

compared to sows from other Midwestern states (Bunnell and Tait 1981, Etter et al. 2002, Rogers

1987a). Males are sexually mature at two years of age but typically do not participate in

breeding until four to five years of age (Ternent 2005).

Breeding season for black bears occurs during the summer, the peak being from mid-June to

mid-July (Alt 1982 and 1989). Female’s exhibit delayed implantation (Wimsatt 1963); eggs are

fertilized immediately but development is suspended at the blastocyst stage. In Pennsylvania,

implantation typically occurs between mid-November and early December (Kordek and Lindzey

1980). Delayed implantation postpones any nutritional investment until after the critical fall

foraging period (Ternent 2005). If a fall food shortage results in a reduction in fat reserves the

blastocysts can be absorbed. A reduction in nutritional investment in a poor food year allows the

female to breed again the following summer if nutritional resources are more favorable (Ternent

2005).

Cubs are born helpless and hairless, typically in January while females are in the den. Cubs

weigh 10 to 16 ounces at birth but because of high fat contents in their mother’s milk, they grow

quickly (Ternent 2005). By the time the female and cubs exit the den (generally late April), the

cubs will weigh between five and nine pounds. By the end of their first summer, cubs typically

weigh 50 to 60 pounds. Cubs stay with their mother for about a year and a half, denning together

the winter after birth and separating in late May the following spring. Adult females typically

breed every other year.

Mortality

Black bears are relatively long lived, and disease and starvation contribute little to adult bear

mortality. Black bears in Michigan have few natural predators and are rarely killed by wolves in

3

the UP (DNR, unpublished data). Most recorded mortality in Michigan is from hunting or

vehicle collisions.

Intestinal parasites such as roundworms and tapeworms are common in bears but they rarely

interrupt digestion or affect nutrition (Quinn 1981). The tissue parasites Toxoplasma gondii and

Trichinella spiralis are found in black bears but are not thought to cause mortality (Schad et al.

1986, Briscoe et al. 1993, Dubey et al. 1995).

Bovine tuberculosis has been detected in bears in northeastern Lower Michigan, an area known

to have bovine tuberculosis (TB) in the white-tailed deer herd. From 1996-2003, 3.3% (7 of

214) of bears tested from this area were positive for bovine TB (O’Brien et al. 2006). Bears

likely contract this disease while feeding on carrion or deer gut piles left behind by hunters.

Bears which test positive for bovine TB do not show the physical signs (e.g., lesions in the lungs)

and bears likely serve only as a dead end host and not as a source of infection for other animals

or humans (O’Brien et al. 2006).

In Michigan, black bears have been known to live up to 28 years of age (DNR, unpublished

data). Annual survival for yearling and older bears in Michigan’s NLP was 78% and hunting

accounted for nearly 60% of annual mortalities (Etter et al. 2002). Overall cub survival for the

NLP was 75% and within the range reported by other studies (Kasbohm et al. 1996, DeBruyn

1997, McLaughlin 1998). However, cub survival varies annually and has been linked to the

availability of natural foods, particularly soft and hard mast (Jonkel and Cowan 1971, Rogers

1976, Young and Ruff 1982). Additionally, cub mortality occurs at a higher rate in a sow’s first

litter than in subsequent litters.

Human related mortality (e.g., hunting, vehicle collisions), is the primary source of mortality for

black bears in Michigan (Etter et al. 2002) and across North America (Bunnell and Tait 1981,

Schwartz and Franzmann 1992). Mortality rates for males are typically greater than females

(Hamilton 1978, Bunnell and Tait 1981, Hellgren and Vaughan 1989) and are associated with

greater vulnerability of males (particularly yearlings) to human and natural mortality factors

(Bunnell and Tait 1981, Rogers 1987a).

Motor vehicle-bear collisions account for fourteen percent of bear mortalities in the NLP (Etter

et al. 2002); the frequency of these events increases with increased bear density, human

populations, and traffic volume. However, other factors (e.g., habitat and natural food

availability) likely contribute to localized and seasonal variation in vehicle-bear collisions.

Habitat Requirements

Black bears are most frequently found in large, heavily forested areas. In Michigan, bears tend

to use a mixture of vegetation cover types including deciduous lowland forests and coniferous

swamps, mature and early successional upland forests, and some degree of forest openings

consisting of grasses and forbs. Diverse forests are prime habitat as they provide the variety of

cover and food sources which bears require to meet their seasonal needs.

Forested swamps and regenerating clear cuts provide much of the escape and resting cover bears

require. Mature upland forests provide hard mast (e.g., acorns, beechnuts, hickory nuts,

4

hazelnuts), while early successional forests provide soft mast (berries) and diverse herbaceous

ground flora. Forest openings are important for food resources such as emerging grasses,

herbaceous vegetation, insects, and soft mast.

As black bears continue to move into the SLP, it has become clear they can inhabit a highly

fragmented landscape, provided some forested areas exist, especially along riparian zones

(Carter 2007). Black bears are also becoming more common in suburban and exurban areas

throughout their range (McConnell 1997, Lyons 2004, Wolgast et al. 2005, Beckman and Lackey

2008). Some aspects of human activity contribute to suitability of these areas including

abundant food from row crops, orchards, apiaries, bird feeders, and human refuse.

Food Habits

Black bears are omnivorous and opportunistic feeders, using both plant and animal matter.

Approximately seventy-five percent of their diet consists of vegetation (Ternent 2005). In early

spring, bears frequent wetlands feeding on plants such as skunk cabbage, sedges, grasses, and

squawroot (Ternent 2005). Fruits and berries are important during summer and fall, including

blueberry, elderberry, blackberry, June berry, pokeberry, wild grapes, chokecherry, black cherry,

dogwood, and hawthorn. Hard mast from oaks, beech, hickory, and hazelnut become important

in the fall as bears accumulate significant fat reserves for the winter. Bears feed heavily in the

fall and can gain as much as 1 to 2 pounds per day. Bears are capable of doubling their body

weight between August and December when mast is abundant (VDGIF 2002). When fall foods

are scarce, bears tend to den earlier which can impact hunter harvest.

The majority of animal matter consumed by bears includes colonial insects and larvae such as

ants, bees, beetles, and other insects (Pelton 1992). However, bears are opportunistic feeders and

they are capable of preying on most small to medium sized animals including mice, squirrels,

woodchucks, beaver, amphibians, and reptiles. Under certain conditions bears may actively hunt

for newborn white-tailed deer fawns. In north-central Minnesota 86% of fawn deaths from birth

to 12 weeks of age were caused by predators and bears accounted for 29 to 36% of the kills

(Powell 2004). Bears in Pennsylvania accounted for 25% of fawn mortalities to 34 weeks of age

(Vreeland 2002). When available, bears also feed on carrion.

Human-related foods include agricultural crops (e.g. corn, apples, peaches, and cherries),

apiaries, bird feed, and garbage. Pet and some livestock foods are sometimes eaten by bears,

especially when readily available or in years when natural food supplies are poor.

Denning Behavior

Black bears enter a period of winter dormancy for up to six months as an adaptation to food

shortages and severe weather conditions. In Michigan, bears typically enter the den by

December and timing of denning varies annually depending on food availability. Pregnant

females tend to den first and adult males are the last to den. Den emergence typically occurs in

late March and April; adult males generally leave dens earlier than females, and females with

newborn cubs generally emerge latest (Rogers 1987a, O’Pezio et al. 1983).

Unlike true hibernators who have body temperatures that drop to near ambient conditions, black

bear body temperatures decrease only slightly to 31-36°C from a normal range of 37-38°C (Folk

5

et al. 1972 and 1976). Heart rates and metabolism decrease in the den and although they appear

lethargic, bears are easily awakened and capable of fleeing immediately if they feel threatened.

Bears do not eat, drink, or defecate during winter dormancy and basic protein and water needs

are partially met by recycling urea, while other adaptations such as shivering and nutrient

recycling reduce the loss of muscle tone and bone density (Ternent 2005).

Black bears use a variety of den locations and generally select sites that minimize heat loss and

allow conservation of energy. Dens may be excavated or constructed as ground nests. Bears

will also den in rocks cavities, root masses, standing trees, openings under fallen trees, and brush

piles. Dens are often lined with dead grass, leaves, and small twigs. Locations vary from year to

year; however, the occasional reuse of dens has been documented in Michigan.

Bears can lose up to 25-30% of their body weight during denning, and after emergence, bears

may continue to lose weight while searching for scarce early spring foods that tend to be low in

nutritional value (VDGIF 2002). Lactating females raising cubs may be stressed nutritionally

after leaving their dens

Home Range, Movements and Activity

Black bears shift activity patterns seasonally in response to the availability of food. The area that

a bear occupies seasonally or annually is referred to as its “home-range.” The size of home-

ranges typically varies by the sex and the age of the bear. The home-range size of a mature

female is influenced by whether or not she has cubs. Females with newborn cubs have smaller

home ranges that gradually increase as cubs mature (Ternent 2005). Annual male home ranges

are generally larger than females. In Michigan, mean annual home range size for males and

females were among the largest reported for the species (Etter et al. 2002). Females in the NLP

had an average home range size of about 50 square miles, and males had an average home range

size of about 335 square miles. Home ranges of female bears generally overlap, but overlap of

mature male home ranges is less common. The home range for a single adult male may

encompass several female home ranges. Young males disperse away from their natal home

range before establishing a new territory, whereas young females are less likely to disperse and

sometimes occupy areas that include portions of their mother’s home-range (Ternent 2005). In

the NLP, 32 percent of radio-collared yearling females dispersed from their natal home range

and 95 percent of radio-collared yearling males dispersed from their natal home-range (Etter et

al. 2002). Male bears dispersed an average of 14 miles in Pennsylvania (Alt 1977 and 1978).

Black bears are most active at dusk and dawn. Nocturnal activity is uncommon, but may occur if

bears are avoiding daytime disturbance by people (Ternent 2005). Black bears can travel long

distances to exploit concentrated food sources such as soft and hard mast, human refuse, and

agricultural crops (Garshelis and Pelton 1981, Rogers 1987b). Activity intensifies during the

breeding season and again in the late summer and fall when foraging increases.

Social Structure

Black bears are solitary animals with the exception of females accompanied by cubs or yearlings,

and during the breeding season when mature males and females can be seen together. Bears

establish and maintain a dominance hierarchy by using threatening gestures and sounds including

stamping feet, charging, huffing and chopping jaws (Rogers 1977). Fights among bears are

6

uncommon except by males during the breeding season when they are competing for females or

when females are protecting young (Ternent 2005). A communal rubbing tree where bears rub,

bite and claw is another of communication and these trees are assumed to be used as part of the

process of establishing a social structure within the population. Tree rubbing peaks during the

summer and multiple bears may mark the same tree (Ternent 2005).

Assessment of Bear Populations

The DNR estimates the long-term trend and size of bear populations to help understand bear

population dynamics, evaluate whether annual harvests achieve desired management objectives,

and to help make recommendations for annual harvest quotas to the Michigan Natural Resources

Commission (NRC). For the purpose of assessing bear populations, the State is divided into

three ecological regions or land types (Albert 1995). The regions include, Eastern Upper

Peninsula (EUP), Western Upper Peninsula (WUP), and NLP. The DNR uses a combination of

multiple population indices, population estimators, and population models to assess the bear

population on a regional and statewide basis. Primary sources of data used in population indices,

estimators and models are derived from a combination of information from the published

literature, field surveys, mandatory registration of harvested bears, and an annual mail survey of

bear hunters. Field surveys include historical radio-telemetry projects, bait station surveys, and

additional research projects found in DeBruyn (1997), Etter et al. (2002), Etter and Mayhew

(2008); Mayhew and Etter (2008); Visser (1993; 1995; 1996; 1997; and 1998) and Winterstein

and Scribner (2004).

Since 1982, all successful Michigan bear hunters have been required to register their bear at a

DNR registration station within 72 hours of the time of harvest. A bear patch was developed in

1985 to encourage hunters to register their bear and to make the carcass available for the

collection of biological data. Patches were given free to successful bear hunters who brought

their bears to registration stations until patches were discontinued in 2007 as a cost saving

measure by the DNR. Starting in 2008 patches will be available for a fee from Michigan Bear

Hunters Association (MBHA). Profits from the patch program will be donated by MBHA to the

DNR for use in bear and wildlife education efforts.

Registration information collected by the DNR includes the harvest location of the bear, date

harvested, and sex of the bear. A pre-molar tooth is extracted and used to age the bear by

counting cementum layers after the tooth is cross sectioned (Hildebrandt 1976, Willey 1974) and

the reproductive tracts of female bears have been collected periodically to assess reproductive

history. Knowing the age of bears harvested is essential for calculating several population

indices and helps in the development of population models. The pre-molar tooth provided by

successful hunters is also essential for estimating bear populations in the UP and NLP using

capture-recapture methods (described below).

Annual mail surveys of a randomly selected subset of bear license holders have been conducted

in most years since 1982 (Frawley 2008). The purpose of these surveys is to provide an estimate

of bear harvest and to collect additional data used in the calculation of several bear population

indices.

7

Bear Population Indices

The use of indices to monitor wildlife populations is a common wildlife management practice

(Lancia et al. 1996), and many agencies use a variety of indices for evaluating bear populations.

Bear population indices measure an attribute of the population and can be used independently to

monitor changes in population status. While indices do not estimate or enumerate the number of

bears in a population, they can be used to determine whether the population is increasing,

decreasing, or is stable over time. Indices determine population trends over multiple years and

are not reliable indicators of annual changes in population size unless a known relationship

between the index and the population is determined. The DNR considers the logistics of data

collection including cost, data reliability, and ability of the index to detect population change

when selecting an index. Use of multiple indices strengthens the assessment of population status

and the DNR uses several indices (described below) to monitor regional bear populations.

Hunter Harvest

In theory, mandatory registration provides a total count of the number of bears harvested

annually. Hunter compliance with mandatory registration is high based on comparisons between

registration results and mail survey estimates of the harvest (Frawley 2008). Changes in the

harvest from season to season are related to changes in the size of the bear population as well as

population-independent factors such as the availability of natural foods, weather, and hunter

experience.

Hunter Success and Hunter Effort

The responses of hunters to questions in the annual mail survey are used to estimate the number

of bears harvested, the days of “effort” required to harvest a bear, and overall success of hunters

in a region. When other factors are equal, trends in hunter effort and hunter success are believed

to reflect changes in the bear population. Hunter effort is inversely related to population size,

that is, as the population declines, the effort required to harvest an individual animal increases.

Hunter success is positively related to population size because as the population increases,

individual hunter success also increases.

Bait-station Surveys

Bait-station surveys have been used to monitor the status of Michigan’s bear populations since

the mid-1980s. Annual changes in visitation rates by bears to a baited area are used as an

indicator of changes in the bear population. Baits, usually bacon or sardines, are suspended from

a tree in a fashion that makes it difficult for animals other than a bear to access the bait. Baits are

spaced approximately one-half mile apart along roads and trails to reduce the chances of a single

bear taking multiple baits. Baits are checked after one week and the number of sites visited by

bears is determined to produce a visitation rate. Visitation rates are related to population size

because it is assumed that as the population decreases, fewer baits are visited by bears.

Harvest Age and Sex Distribution

Changes in the age distribution of harvested bears may reflect real changes in bear reproduction

and survival. If natural mortality and reproduction of a population are stable, a change in age

distribution over time towards a higher proportion of younger animals is thought be indicative of

8

an exploited population. Younger black bear populations can be less productive because most

female bears in Michigan are not sexually mature until 3 to 5 years of age.

Bear Population Estimators

Population estimators attempt to enumerate population size. Some population estimators allow

calculation of confidence intervals around a mean estimate, effectively providing a range of

estimates. Efforts are made to track and estimate populations at the regional level, but some of

the estimators lack sufficient data to produce separate estimates for the EUP and WUP. In those

cases all the UP data are combined to produce a single UP estimate.

Population Reconstruction

The bear population can be “reconstructed” by using known ages from individual bears.

Mandatory registration of all harvested bears and the cementum aging of bear teeth provide the

data necessary to reconstruct bear populations. However, population reconstruction from harvest

data provides only an estimate of the minimum population size in the relatively recent past (i.e.,

5 to 7 years ago) because bears can live to greater than 20 years of age. Additionally, hunting is

only one source of mortality for bears. An estimate of the total population can be obtained from

harvest data by dividing minimum estimates by a lifetime recovery rate (Roseberry and Woolf

1991) which for UP bears is less than fifty percent (Mayhew and Etter 2008).

UP Tetracycline Capture-Recapture Estimator

Since 1989, a tetracycline based capture-recapture survey has been used to estimate the size of

the UP bear population (Garshelis and Visser 1997, Mayhew and Etter 2008). Tetracycline is an

antibiotic that binds to calcium in bones and teeth, and fluoresces under ultraviolet light.

Tetracycline-laced baits are placed across the UP in the summer. Baits are suspended from a tree

in a fashion that makes it difficult for animals other than a bear to access the bait. A bear

becomes “captured” or “marked” when it consumes bait laced with tetracycline. By marking a

large number of bears using tetracycline-laced baits and later collecting and examining the teeth

from hunter-harvested bears (“recaptured”), an estimate of population size can be calculated.

Tetracycline-based population estimates have not been derived for Drummond Island (DI) or the

NLP. Tetracycline-based population estimation was attempted for these areas in the mid-1990s.

On DI, an insufficient sample of marked bears was obtained without risking “double-marking”

bears (i.e., bears that take greater then one tetracycline bait). Additionally, the low number of

bear harvested annually on DI reduces the probability of recaptures and influences the estimate.

An additional issue in the NLP was the inability to identify an unknown source of tetracycline in

some bears. This may have been the result of bears consuming honey or bees from apiaries

because bee keepers often use tetracycline to treat bees.

NLP Genetic Capture-Recapture Estimator

The same principles that are used for the tetracycline capture-recapture estimator also apply to

the NLP Genetic Capture-Recapture Estimator. The difference is that individual bears can be

“captured” or “marked” and later identified with genetic techniques using hair and tissue samples

(Dreher et al. 2007, Etter and Mayhew 2008). Bears are attracted with bait to a barbed wire

“snare” configured around three to four closely spaced trees. Bears deposit hair samples while

9

navigating through the barbed wire to access the bait. For several weeks during the summer, hair

snares are checked and samples collected. Deposited hair follicles, which contain DNA, are used

to identify individual bears from each sample period (one week). A final recapture event

includes collection of tissue samples (contained in teeth) from each bear harvested from the

NLP. This technique has advantages over the tetracycline capture-recapture technique because

individual bears can be identified using DNA, whereas the tetracycline technique does not allow

for identification of individual bears unless they are recaptured in the harvest. This difference

allows for the use of more sophisticated statistical models potentially increasing the accuracy and

precision of the bear population estimate. However, the genetic technique is much more labor

intensive and costly than the tetracycline technique, making it prohibitive to operate in the UP

where the bear population is considerably larger and many more bears are harvested annually.

Bear Population Model

Population models also attempt to describe the population based on past and present

demographic information including harvest data. The population model currently being used by

the DNR was developed in 1984 by the Minnesota DNR (Garshelis and Snow 1988), and was

subsequently upgraded by Minnesota and Wisconsin researchers. The model is a conceptually

simple accounting type model based on a variation of the equation:

N

t+1

= N

t

+ B

t

– D

t

where N

t

is the population size at time t, B

t

is the number of bears recruited to the population

through births, and D

t

is the number of deaths of bears alive at time t. In the model, immigration

(bears moving into the population from an outside source) and emigration (bears dispersing from

the population) are considered equal. The model is deterministic which means that each run with

the same inputs will produce identical results. There is no component of random variation and

therefore no confidence intervals are produced in the output. The necessary model inputs

include: 1) a starting and ending year, 2) a starting population size, 3) an initial sex and age

composition, 4) reproductive parameters (litter size, cub sex ratio, and percentage of females

producing cubs at each age), 5) natural and other human-caused mortality rates, and 6) harvest

mortality (actual number). All mortality parameters are sex and age specific. Input parameters

used to model the bear population are derived from population estimates from Michigan surveys,

information from the published literature, research conducted in Michigan, and data from the

annual bear harvest.

Current Population Status and Range in Michigan

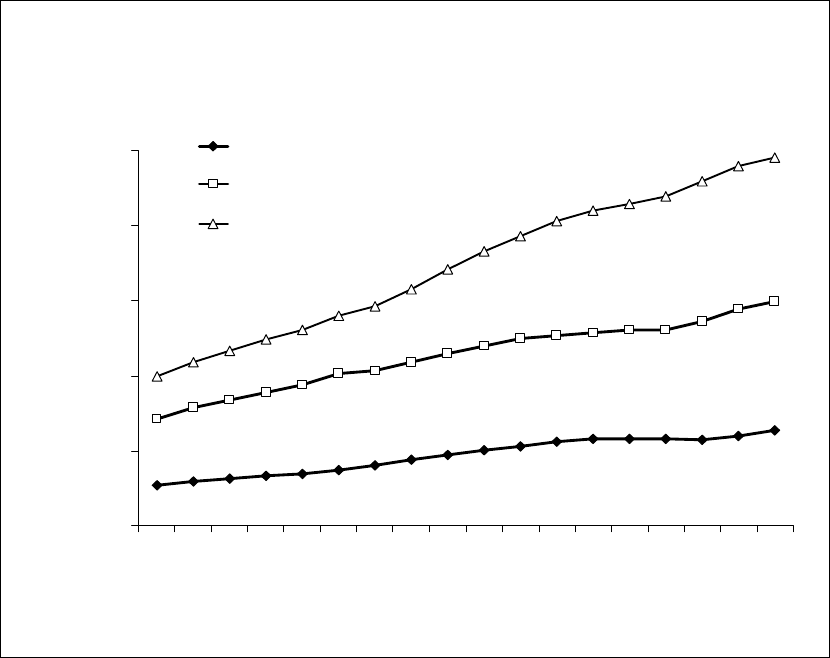

Bear populations in Michigan have been steadily increasing since at least the 1990s (Figure 1).

An estimated 19,000 bears (including cubs) occupy approximately 35,000 square miles of

suitable bear habitat in the UP and NLP. Greater than eighty-five percent of the bear population

resides in the UP where large tracts of state, federal, and private commercial forest lands contain

good to excellent bear habitat. Bear populations in both Peninsulas are believed to be stable to

increasing, and an increasing number of bear observations in southern Michigan suggest that

bears are expanding from the NLP into the SLP.

10

Simulated Late Summer Model Estimates of the Number of

Bear (including cubs of the year) in Michigan, 1990-2007.

0

2100

4200

6300

8400

10500

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

Year

Estimated Number of Bear

Northern Lower Peninsula

Eastern Upper Peninsula

Western Upper Peninsula

Figure 1. Simulated late summer model estimates of the number of bear in Michigan, 1990-2007.

Black bears are relatively common north of a line from Muskegon to Saginaw. Bears are less

common and in some cases likely only seasonal transients in much of the area south of this line.

A simulated model of preferred bear habitat indicates that less than three percent of the

landscape in southern Michigan is suitable for black bears (Carter 2007). However, this model

was based on data collected from radio-collared bears that resided in the NLP and may not fully

describe the potential for bears to become established in southern Michigan. For example, bear

populations are expanding and growing rapidly in New Jersey, the most densely populated state

in the nation (McConnell 1997). Bears living on the fringes of suburbs in Southern California

have altered their foraging times to later at night when human activity is minimal (Lyons 2004).

Based on these references and an increasing number of bear observations, southern Michigan

may provide better bear habitat than predicted by the simulated model.

11

Harvest Management

Legal Authority

The DNR has a public trust responsibility for the management of all wildlife species and

populations. Primary legal authority for wildlife management and regulation comes from the

Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act, Public Act 451 of 1994. Part 401 of

Public Act 451 gives authority to the NRC and the DNR Director to issue orders (the Wildlife

Conservation Order) specific to wildlife management and hunting.

In 1996, Michigan voters supported a hunting ballot initiative requiring the NRC to use

“principles of sound scientific management” in making decisions concerning the taking of bear

and other wildlife. This legislation also gave exclusive authority to the NRC over the method

and manner of take for game species. Following passage of the initiative, it was codified as

Section 40113a of Public Act No. 451 of the Public Acts of 1994, MCL 324.40113a.

A Brief History of Bear Hunting in Michigan

Sport hunting of black bears was first regulated in 1925 when the Michigan legislature declared

the species a game animal. Prior to 1925, bears could be taken at any time and by any means. In

1939, the legislature rescinded statewide bear regulations, but authorized the Conservation

Commission (now the NRC) to grant protection for bears in counties requesting it. Using bait

for bear hunting has always been legal in Michigan and hunting bears with dogs became legal in

1939. Cubs were first protected in 1948, and in 1952 the legislature empowered the NRC to

open or close bear hunting seasons as necessary, and to prescribe methods of take. Also in 1952,

bear trapping was outlawed except under special permit.

In general, bear hunting opportunities coincided with the firearm deer hunting season through

1952. The first and only spring bear season (April 1-May 31) was held in 1953. Early (August

15-September 15 in the UP, and October 1-November 5 in the LP) and late fall (November 15-

30) hunting seasons were established and continued through 1964. In 1965, bear hunting was

closed in the NLP due to concerns about a declining bear population and limited hunting

opportunities in the NLP resumed in 1969.

The first bear hunting stamp (license) was issued in 1959. However, only small game license

holders who were interested in hunting bear were required to affix the stamp to their license. The

stamps were issued through 1963. From 1959-1963, firearm deer license holders were not

required to possess a stamp to harvest a bear during the firearm deer season. During the 1964

and 1965 seasons, a separate bear license was required of all bear hunters. Again, between 1966

and 1979, firearm deer license holders were not required to possess a stamp to harvest a bear

during the firearm deer season. It was not until 1980 that a separate bear license was required.

In 1990, bear hunting was placed under a zone and quota system which is still in use today, and

during the same year it became illegal to take bear during the November firearm deer season.

12

When regulated, the bag limit has been one bear per year per person in Michigan. Beginning in

1995, it became unlawful to take a female bear accompanied by cubs. Hunters in Michigan

usually use bait, dogs or a combination of both to pursue bear (Frawley 2008).

Current Management Areas

Regions

To facilitate the management of bears, primary bear range in Michigan is broken into three

ecological regions; the Eastern Upper Peninsula (EUP), Western Upper Peninsula (WUP), and

Northern Lower Peninsula (NLP). Drummond Island (DI) at the east end of the Upper Peninsula

is semi-isolated and a unique habitat for bears and thus is managed separate from the UP and

NLP. Population dynamics are assessed relative to the ecological characteristics of each distinct

ecoregion. Although populations of bears are not physically isolated by ecological boundaries

(i.e., there is not complete demographic closure among regions), differences in genetic

population structure are evident between the UP and NLP suggesting that movements of bears

between the two peninsulas are infrequent (Lopez 2004).

Bear Management Units

In 1990, a zone and quota system was established to regulate the bear harvest and limit the

number of bear hunters in specific areas. Ecological regions (EUP, WUP and NLP) are presently

divided into 11 zones called Bear Management Units (BMUs; see 2008 Michigan Bear Hunting

Guide). Bear Management Units are designed to help distribute hunters and thus the bear harvest

throughout the entire ecological unit, rather than allowing hunters to target animals only in

optimal habitats. Some BMUs have only one time period when hunting is allowed, while others

have several, sometimes overlapping, hunt periods. By distributing hunters throughout the

ecological region, BMUs also help to assure that biological information obtained from harvested

bears is representative of the entire region’s population. Boundaries of BMUs typically are

established as clearly recognizable roads, rivers or county lines for the benefit of hunters and to

assist with law enforcement.

Quota System for Distributing Bear Hunting Licenses

Because of increasing demand for bear hunting opportunities, in 1990, a quota system was

established to limit the number of bear hunters and to better influence the distribution and

density of hunters in the different BMUs. Under the quota system, the number of hunters

participating in each unit and hunt period is limited by the number of licenses issued to achieve a

desired bear harvest but still maintain a high level of recreational opportunity. Under this

system, beginning in 2000, individuals that apply for a bear license receive a preference point

each year that they apply for a bear license but are unsuccessful at drawing a license. In the

drawing, applicants with the greatest number of points in each BMU and hunt period are issued

licenses first. Applicants may opt to receive a preference point only, and bank the point for

future drawings. Beginning in 2007, applicants could indicate a second choice hunt which is

considered if all licenses for the first choice hunt are awarded. The second choice hunt was

established to provide additional hunting opportunities and meet the desired harvest levels.

Black bear populations have increased over the years (Figure 1), leading to more hunting

opportunity and increased license availability. However, during the same period, there has also

13

been an increase in the number of bear hunters (Frawley 2008). This has lead to increased

competition for licenses in some BMUs. Odds of drawing a license are specific to each BMU

and hunt period. The number of hunters applying for licenses increased most years from 1990 to

2004, but has been relatively stable for the last four years.

Because approximately 85 percent of Michigan’s black bears are in the UP, there are also more

bear hunting opportunities in the UP. Over 80 percent (approximately 10,000) of the 12,000

possible licenses were available in the UP in 2007 and similar opportunities are available in

2008.

Current Bear Hunting Periods

The timing and length of bear hunting seasons varies throughout the state in order to achieve

desired harvest levels, while at the same time providing ample recreational hunting opportunities.

Additionally, the number of hunters who desire to hunt in a particular region also varies. In

general, bear hunter demand is highest in BMUs with a combination of high bear densities and

close proximity to higher human populations. Currently, bear hunting seasons occur in mid-

September in the NLP and from September 10 through October 26 in the UP. There is also an

archery-only season in early October in the Red Oak BMU in the NLP. The season in the UP is

arranged in three overlapping hunt periods. The first hunt period has a five day quiet period

from September 10-14 during which dogs may not be used.

These seasons were determined over time using a combination of biological and social factors.

Hunting success, particularly for hunters not using dogs, is most closely tied to periods of natural

food availability. When there is an abundance of natural food, hunting success tends to decrease

(MacDonald 1994). Prior to mid-September, both soft and hard mast is available in abundance,

suggesting that in most years hunting success would be relatively low during this time. A second

consideration is the effect of weather, both on bear movement patterns and the resulting hunter

success levels. Meat care may also be an issue in some areas. Higher temperatures, particularly

in inland areas and earlier hunt periods, may result in meat spoilage.

Land Ownership

Black bears are generally forest animals and forested cover types and land management practices

within these cover types can impact available habitat for bears. Michigan has nearly 19 million

acres of forest land, and approximately 65% is privately owned. The DNR manages

approximately 3.9 million acres of forest land scattered across the UP and NLP. Slightly more

than half (51.6%) of DNR owned forest land is located in the NLP eco-region. The EUP and

WUP eco-regions contain 26.5% and 21.9% of forested cover types, respectively (Michigan

State Forest Management Plan 2008). Approximately 35,000 square miles of suitable bear

habitat is located in the UP and NLP (Bostick et al. 2005).

Ownership patterns provide unique challenges for bear management. In general, public lands

consist of good bear habitat (mostly forested); whereas private lands vary in the quality of habitat

they provide. Individual bears have large home-ranges and seasonal movements of ten to twenty

miles are common for black bears. Mature males in Michigan have been known to move even

greater distances during the breeding season. As bears move across the landscape they cross

14

multiple jurisdictional boundaries and private land parcels. Land uses and management practices

vary widely across bear range, particularly on private lands. Because of these various uses and

practices, bears may be in conflict with some private land owners while others may want to

attract bears to their property for viewing or hunting opportunities. Additionally, access to

private lands to hunt bears is also limited by the property owner which can influence bear harvest

in different areas of the state. In the UP, approximately 40 percent of lands are in public trust

(state and federal lands), 20 percent are in private ownership, but open to the public through the

Commercial Forestlands Act, and the remaining 40 percent are in private ownership. In the NLP

(Zone 2; see 2008 Michigan Hunting and Trapping Guide), approximately 31 percent of lands

are in public trust, less than 1 percent are in CFA agreement, and 68 percent are in private

ownership. In the SLP (Zone 1, see 2008 Michigan Hunting and Trapping Guide) less than 5

percent of lands is in public trust, with the remainder in private ownership.

Population Goals

Wildlife managers often develop goals for wildlife species whose numbers can be influenced

through management actions. Population goals can be important targets sometimes established

as a function of the biological and social carrying capacity (see below). If population goals are

established, factors such as a species’ life history, available habitat, land use and ownership

patterns, habitat management plans, wildlife-human interactions, and social tolerance must be

considered. Natural resources decision makers can use established population goals to direct

management policies and impact resource allocation for wildlife species.

There are two different types of population goals that can be developed for black bear

populations: qualitative goals and quantitative goals. Qualitative goals are based on the social

desires for a particular abundance of bears in an area. The actual population does not need to be

enumerated, but rather stated as “not enough,” “too many,” or “just the right amount” of bears

relative to a desired social attribute. From a management standpoint, biologists can state desired

population goals as increase, decrease, or maintain the bear population relative to current levels.

Qualitative goals can also be stated relative to quantitative measures. For example, there may be

a social desire to maintain a certain level of bear hunter satisfaction, or minimize bear-nuisance

complaints. Both of these “indices” can be measured quantitatively, but they still reflect a social

desire relative to attitudes towards bears. Qualitative goals also can be measured against

enumerated population levels if the bear population can be estimated accurately. However, this

approach should be viewed with caution because accurate estimates of wildlife populations are

difficult and expensive to obtain, and social attitudes towards wildlife change frequently due to

factors that may or may not be related directly the relative abundance of a species.

Quantitative population goals attempt to identify a desired population size or a numeric range

within which the population is considered to be at the desired goal. Black bear management

plans that establish quantitative population goals require more intensive data collection and

analysis compared to those using qualitative goals. Population size estimates are generated from

data sets that often require intensive field collection efforts. Staff time and available funding can

be constraints to conducting this level of data collection. Although more data intensive, numeric

population goals and their requisite population size estimates can offer an advantage over

qualitative goals by determining the degree to which a population is over or under goal.

15

Regardless of the type of goal used, it is important that population goals be adaptive to changes

in the landscape, relative abundance of bears, number of hunters, and social attitudes. Presently,

the DNR uses a combination of qualitative and quantitative goals to manage the state’s bear

population.

Management Strategies

Public Act 451 requires that the DNR use sound science when making bear management

decisions. Scientific information is obtained from research, in-state surveys, and published

literature. Social issues associated with bear-human interactions (both positive and negative) are

also important factors that must be considered when making decisions regarding the harvest of

bears in Michigan. Qualitative social information is obtained from discussions with tribal

governments, stakeholders, DNR field staff, and other agency staff. Quantitative social

information is obtained from surveys such as the annual “Michigan Black Bear Hunter Survey”,

which asks questions pertaining to specific management options or objectives. Additional

quantitative social information, not necessarily associated with hunting, is also obtained through

surveys (e.g., Peyton et al. 2001).

Scientific management incorporates the concept of adaptive resource management, an iterative

process by which changes in management actions (e.g., hunting regulations, or educational

efforts) are evaluated to determine if these changes achieve management goals. Management

efforts over time are modified as new information is obtained, new analyses are conducted, or

factors that influence bear ecology change.

The current bear management program includes research to help understand the ecology of bear

and social acceptance capacity of Michigan’s residents. In addition, the DNR provides

information to the public about bears and technical assistance to landowners with unwelcome

bear encounters. Sport hunting has the capacity to influence abundance of black bears, provides

recreational opportunities, and is an important tool used to manage the size of Michigan’s bear

population.

The mission of the Department’s black bear management program is to maintain a healthy black

bear population that provides a balance of recreational opportunities for residents while at the

same time minimizes conflicts with humans. To fulfill this mission, the DNR has established six

strategic bear management goals focusing on populations, recreational opportunity, and

education.

Population

1) Maintain long-term, viable populations of bear within habitats suitable for the species.

2) Maintain bear populations at levels compatible with land use, recreational opportunities, and

the public’s acceptance capacity for bears.

3) Manage black bear habitat to provide for the long-term viability of the species.

16

4) Use hunting as the primary tool to help achieve population goals.

Recreation

5) In addition to hunting, provide bear-related recreational opportunities which recognize the

aesthetic value of bears.

Education

6) Promote education about bears, bear-related recreational activities, and how to minimize

negative human-bear interactions.

Regulatory Process

Establishment of Bear Harvest Objectives and License Quotas

Each year, population estimators, indices, and models are updated by the state bear specialist and

research biologist. This information is forwarded to members of the Bear Management

Workgroup, Management Unit Supervisors (MUS), tribal governments in the 1836 ceded

territories, and other interested agencies. Workgroup members and the supervisors meet with the

wildlife habitat biologists in their respective areas to assess the status of local bear populations

and determine harvest levels necessary to manage populations at desired levels. They also

discuss any issues relevant to bear management that would require changes to regulations.

Government-to-government consultations with the 1836 Treaty Tribes are conducted to discuss

harvest quotas and any proposed regulations changes. Additional meetings with US Forest

Service or other agency biologists may occur to discuss management issues of particular interest

to these groups. Further, the DNR receives feedback and information on bears and bear

management on a continual basis from user groups interested in bears, from agricultural groups,

and from the general public. Perceived or measured social tolerance (which varies

geographically) is given strong consideration when making harvest recommendations. After

taking all of the available biological and social information into consideration, and weighting the

factors appropriately for their management unit, MUSs forward to the field coordinator and

statewide bear specialist their regional population trajectory recommendations (e.g., increase,

decrease, or stabilize the regional population) and any other proposed changes to bear hunting

regulations. The bear specialist reviews these recommendations in the context of statewide

issues and needs. Any conflicts are moved to the species section supervisor and field coordinator

for resolution.

The regional (EUP, WUP or NLP) bear population model is used to determine the level of

harvest required to achieve these goals. This harvest level is termed the “desired harvest” and is

represented by the number of bears in a region that would have to be harvested during the

hunting season in order to allow the population to reach the population trajectory goal.

Once the desired harvest levels for each region have been established, the MUSs distribute the

proposed regional harvest among BMUs within that region. In the UP where there are three hunt

periods, the desired harvest is first distributed equally among hunt periods and then the number

17

of licenses is calculated to achieve this harvest in each period. The number of licenses (quota)

that will be recommended for each BMU and hunt period is determined using a three-year

running average of license success (bears harvested/number of licenses issued) by hunt period

for each respective BMU. If past license application rates do not appear to be high enough to

achieve the desired harvest in a given hunt period, the harvest is adjusted into other hunt periods

to try to maintain the overall desired harvest and have no leftover licenses. Applicants may

select a first and second hunt choice. If any licenses remain after first and second hunt choices

are awarded, leftover licenses become available to unsuccessful applicants for a week and then

become available to individuals that have not applied for a bear license.

Once these recommendations have been reviewed and approved by all of the DNR Resource

Bureau Division Chiefs and the Director, they are forwarded to the NRC for consideration.

Natural Resources Commission Process

The NRC has an established process for review and approval of all Wildlife Conservation Order

amendments. While a 60-day public review is built into that process, 30 days of public review

are required by Act No. 451 of the Public Acts of 1994.

1) The process begins on the Monday following the regularly scheduled monthly NRC

meeting when the Department submits a memo outlining the recommendations to the

NRC. This action puts the recommendations on the NRC calendar for the following

month and opens a public review period.

2) At the following month’s NRC meeting, the Department typically makes a presentation

“for information” on the recommendations, and questions from the NRC are addressed.

At this time the public has an opportunity to speak before the NRC to voice their

concerns, support, or opposition to the recommendations. The NRC does not take action

to approve the recommendations at this meeting.

3) At the subsequent NRC meeting (approximately 60 days after the recommendation memo

was submitted), the NRC typically takes action on the recommendations. There is

another opportunity for the public to voice their concerns, support, or opposition to the

recommendations. At the end of the meeting, most often the NRC votes on the

recommendations, yet can defer the decision to a later meeting following additional

public comment. If approved, the recommendations become part of the Wildlife

Conservation Order and the Department can take actions to ensure the approved

recommendations are implemented.

Economic Impacts

There are a variety of economic impacts of having bears in Michigan. One economic benefit is

from bear hunting. For example, in Michigan during 1998, an estimated 7,196 hunters spent an

average of 474 dollars per bear hunt, for an estimated total of $3.4 million (Etter et al. 2002).

Baiting and hunting bears with dogs lend themselves to outfitting, and a significant bear

outfitting industry has developed in some areas.

18

Wildlife viewing also contributes to the economy of Michigan. While it is difficult to assess

what portion of wildlife viewing funds are generated due to bears specifically, bears are a

popular, large animal that visitors often seek to encounter. United States Forest Service surveys

indicate that National Forest visitors rank seeing a bear high on their list of desired activities

when recreating in the National Forest system. Over three million people participate in wildlife

viewing annually in Michigan and Michigan ranks sixth in the nation in dollars contributed

($2.68 million) to the economy from wildlife viewing activities (Leonard 2008).

Bears can also cause negative economic impacts. Bears visit apiaries, orchards, row crops,

individual residences and cottages in search of food. Although economic cost estimates are not

available for bear damage on a statewide basis, bears can cause considerable damage. An

individual bear can cause significant damage to bee hives and one bee keeper reported bear

damage costs of $24,000 in a single year (DNR unpublished). Fruit growers and bee keepers

incur costs to erect electric fences and other deterrents to protect their crops from bear damage.

Damage can also occur within privately-owned cervid facilities, when bears consume deer feed

and prey on fawns.

Bear-Human Interactions

Biological and Social Carrying Capacity

The abundance and distribution of black bears in Michigan is influenced by biological carrying

capacity (BCC) and social carrying capacity (SCC). The concept of BCC proposes the

abundance of any wildlife species is limited by the ability of the available habitat to support the

population. The concept of SCC proposes the abundance of a wildlife species is limited by the

human social environment or human tolerance for that wildlife species.

Biological carrying capacity is determined by habitat components such as food, water, shelter

and space, and addresses the maximum population size that can be sustained under varying

availability of these factors. It can be influenced by bear social behavior which is influenced by

bear density. If a population is at BCC, bear productivity may be limited because of later ages of

first reproduction, longer intervals between litters, smaller litter sizes, decreased cub and yearling

survival rates, and greater social conflict. The high productivity and low natural mortality rates

observed in Michigan suggest that the bear populations are below BCC.

While BCC only addresses the maximum population that can be sustained by the available

habitat, SCC is defined by both the maximum and minimum population sizes that society will

tolerate. Issues and conflicts occur when stakeholders disagree on acceptable levels of bear-

human interactions. Bear management often focuses on managing issues created by bear-human

interactions and dealing with the differences in stakeholder values, beliefs, and tolerances

regarding those interactions.

Bear-human interactions can be positive or negative. Positive interactions may include knowing

bears are present in an area, observing bears, and bear hunting. Negative interactions may

include bears causing property damage and people fearful of bears for a variety of reasons. Both

positive and negative interactions are important to stakeholders and influence their tolerances

19

and preferences for bear abundance. Social carrying capacity is determined more by the type of

interactions people have with bears than bear population size per se.

A SCC model was developed in the Lower Peninsula (LP) of Michigan in 2000 by Michigan

State University and the DNR (Peyton et al. 2001). As part of the study, surveys were sent to

6,000 LP residents. Four zones from north to south were identified based on the approximate

density of bears, and mailings were stratified accordingly. Results of the study indicated that 10

percent of the respondents were intolerant of the presence of bears, while 60 percent indicated

they would only become intolerant if they perceived a personal threat by a bear. A greater

proportion of respondents in the most southern stratum were intolerant of the presence of bears

and this proportion decreased in the northern strata. Over 60 percent of the respondents

indicated the existence value of bears was an important benefit, and “the role bears play in

nature” and recreational viewing also were considered important. Recreational hunting was not

seen as a personal benefit by a majority of the respondents.

For addressing problem bears, the most accepted management option was to “leave the bear

alone, provided no one was injured.” The next preferred options were “a carefully regulated

hunt,” and then “capture bears which repeatedly cause problems for people and relocate them to

another part of the LP.” The option to “destroy bears which repeatedly cause problems for

people” was the least favored.

Respondents desired a clear policy and guidelines for managing nuisance bears. They desired

agency employees with training and equipment to implement the policy, and good

communication with the agency concerning the policy and rational. Since completion of this

study, the DNR has developed the Michigan Problem Bear Management Guidelines and

annually conducts training of personnel in the safe capture and handling of bears. A Living With

Bears slide presentation has been created and presented to a number of interested stakeholder

groups. Additional public education materials have been developed and shared with the public,

including a Preventing Bear Problems section on the DNR website at www.michigan.gov/dnr.

Bear-Human Encounters

Black bears are shy, elusive animals, usually flee when encountered, and are generally not a

threat to humans. However, bears are large and powerful animals that have been known to injure

and even kill humans if they feel threatened. Fatal human encounters are rare; from 1900

through the summer of 2005, 57 people in North America have been killed by black bears, while

it is estimated that millions of interactions between people and bears occur annually (Masterson

2006).

Based on reported bear observations in recent years, it is assumed that bears will continue to

expand their range southward into more populated areas of Michigan. At the same time,

residents from urban areas have continued to move into areas traditionally occupied by bears to

the north. These shifts in human and bear demographics suggest that bear-human interactions

are likely to become more common.

20

Baiting and Supplemental Feeding

Black bear hunting is an established tradition in Michigan, and has strong statewide support

among hunting groups. The majority of Michigan bear hunters use bait to attract bears and

improve harvest opportunities. Over 90% of Michigan bear hunters either hunt directly over a

baited site, or use bait to attract bears to a specific site so that they can be hunted with dogs

(Frawley 2008).

Some individuals or special interest groups contend that baiting bears for hunting habituates

bears to human foods and thus increases the likelihood that individual bears will become a

nuisance. However, others contend that bear that visit baits placed by hunters are less likely to

survive or have negative associations with humans (hunters) at bait sites and are thus less likely

to become a nuisance. Neither of these hypotheses have been tested, so it uncertain whether

either is true.

Supplemental feeding of wildlife involves the deliberate placement of foods for the purpose of

enhancing viewing opportunities or augmenting naturally occurring food resources.

Supplemental feeding is not advised by the DNR because of the potential for habituating bears

and making them more likely to become involved with negative bear-human interactions.

Recreational Viewing

Historically, some northern Michigan restaurants and towns maintained open garbage dumps as

feeding sites for the purpose of attracting and viewing bears. Today this practice has been

discontinued in most areas because of improved sanitary requirements meant to protect people

and wildlife. Many Michigan residents and visitors still desire to see black bears in the wild, or

have the opportunity to photograph one. However, recreational viewing of a species that exists

at low relative density is likely to remain a function of local bear abundance, seasonal habitat

quality, time spent afield, and random chance. The best viewing times would coincide with

prime bear activity times of dawn and dusk. Black bears are naturally reclusive animals that tend

to prefer habitats with thick vegetative cover; most bear observations are likely to remain a rare

event.

Orphaned Cubs

Female bears rarely abandon their cubs, but if unexpected sow mortality or persistent site

disturbance (especially den sites) occurs, cubs are sometimes orphaned in the wild. Depending

on the time of year when cubs are orphaned, the chances for their survival are very low. Because

this is a very rare event, the population level implications are minimal. However, popular public

opinion is that the DNR should respond to instances regarding orphaned cubs and make efforts to

return cubs to the wild. The DNR maintains a small number of radio-collared female bears to act

as foster mothers for orphaned cubs. If cubs are orphaned soon after their birth in the winter den,

in many instances they can be successfully added to the existing liters of nursing, radio-collared

sows. After den emergence, female black bears will sometimes accept a foster cub if the

orphan’s scent can be masked and it is placed in the same setting with the sow’s own cubs. In

rare instances if placement with a surrogate mother is not possible, orphaned cubs can be held

21

and cared for by a trained wildlife rehabilitator. After July 1, cubs are considered old enough to

survive on their own and cubs obtained after that date are released to the wild. Zoos or

accredited wildlife facilities are sometimes used as a permanent home for orphaned cubs when

other options are not available.

Bear-vehicle accidents

Most recorded bear mortality in Michigan is from hunting or bear-vehicle collisions. However,

unlike deer-vehicle collisions, the Michigan State Police does not maintain an official database to

track bear accidents. In some areas where bear-vehicle accidents are common, caution signs

similar to deer crossing signs have been placed to alert motorists of the potential for bear

crossings. As the bear population expands into areas of the state with higher human densities,

the possibility of bear-vehicle accidents increases not just in the traditional northern bear range,

but statewide. In the last five years, bear-vehicle accidents have been reported in a number of

southern Michigan counties including Barry, Kent, Genesee, and Muskegon. A mechanism to

gather bear-vehicle accident information has not been established, nor have protocols been

developed to recover bear carcasses resulting from vehicle collisions.

Problem Bear Protocols

The issue of nuisance or problem bear management is complicated, and involves human

behaviors and perceptions, as well as bear behavior. There is a wide range of public opinions as

to what constitutes a bear problem, or a problem bear. To some, the mere presence of a bear is a

perceived problem, while others may enjoy seeing bears on a regular basis. Publications such as

Preventing Bear Problems in Michigan provide useful and proactive suggestions to minimize the

chance of negative bear-human interactions and people can often solve their own bear concerns

before they become a nuisance. However, when bear incidents do occur, the DNR response

follows steps outlined in the Michigan Problem Bear Management Guidelines. Responses range

from providing technical assistance to landowners, to physically removing a bear, to euthanizing

individual bears when public safety is threatened. The information in this guidance document is

part of an educational effort that integrates personnel from DNR Law Enforcement, Wildlife, and

Office of Lands and Facilities staff, as well as local law enforcement agencies and emergency

dispatchers, and in some unique cases, zoos or accredited rehabilitation facilities.

Additional Bear Hunting Issues

Hunter Conflicts

Conflicts sometimes arise between bear hunters and other outdoor users in part due to limited

opportunities to hunt bears and because bear season(s) coincide with a time of increased outdoor

recreation (e.g., other hunting seasons, wildlife viewing). Historically, bear hunters in Michigan

have been permitted to use bait and/or dogs to hunt bears. Both methods are effective,

particularly in rugged areas of Michigan with limited access. Greater than ninety percent of

Michigan bear hunters use bait to attract bears (Frawley 2008). Approximately twelve percent of

hunters use dogs or a combination of dogs and bait.

22

Bear hunters are permitted to establish no more than three bait stations per hunter. Baits cannot

be placed for bears prior to August 10 in the UP or prior to 30-days before the opening of bear

season in the LP (August 19 in 2008). It is unlawful to use man-made materials or a container at

a bait site on public or commercial forest lands (CFL) however, these materials are legal on

private land. One issue related to baiting for bears is that some individuals assume “territorial

ownership” of public lands and they attempt to exclude all other hunters (including hunters of

game species other than bear) from the area they are baiting. Additionally, although bait

containers are illegal on public land some hunters use and leave them when their hunt is done.

Removing this refuse is then at the expense of the land owner (e.g., DNR, USFS, CFL owner).

Complaints about disturbance of bear bait hunters by other outdoor recreationists is also

common, particularly in the NLP where bear season does not open until after many of the small

game (e.g., grouse, rabbit, hare) hunting seasons open. There are additional special deer hunting

seasons open during the bear hunting season in portions of the NLP and these overlapping

seasons also have potential to cause conflicts among hunters.

Bear hunters may pursue bears with dogs except during certain times of year and during certain

periods of the open bear hunting season. These periods of no bear dog activity are commonly

referred to as “quiet periods”. Most bear hunters who use dogs will train their dogs during the

summer before bear hunting season begins. In order to protect nesting birds and young wildlife

during the time of year in which they are most vulnerable, a quiet period was established

between April 15 and July 15; no hunting dogs (includes all hunting dogs) may be trained on

game between those dates except on specially designated state lands or unless the dog handler

receives a permit from the DNR to conduct a special dog hunting field trial. Under current

regulations in the UP, hunters may not pursue bears using dogs the first five days of the first hunt

period. This quiet period was put in place to reduce potential conflicts between hunters using

bait and hunters using dogs. However, in the NLP both methods are permitted simultaneously

throughout the general one-week bear hunting season. Dogs are not permitted for hunting bear

in the Red Oak BMU during the archery-only season (October 5 to 11 in 2008).

Conflicts between bear bait and dog hunters sometimes occur on public lands. Hunters using

bait sometimes complain that dogs chase bears off of their baits, while dog hunters claim that

other factors, not their dogs, are the reason for decreased bear activity at an individual bait site.

Controversies have also occurred between private landowners and dog hunters. Bears have large

home ranges and can potentially cross multiple parcels of land (in both private and public

ownership) while being chased by dogs. This can lead to conflicts between bear dog hunters and