1

RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS

Investigating standards in GCSE

French, German and Spanish

through the lens of the CEFR

Milja Curcin and Beth Black

2

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many people without whose work or advice this study

would not have been possible:

• all our participants, who devoted a lot of their time and enthusiasm to work on

this study and share their expertise and opinions,

• colleagues at Ofqual who have helped in different ways (with IT support,

admin and paper shuffling, analytical support and advice, and various ad hoc

and last minute request for help) – in particular, Nadir Zanini, Joe Colombi,

Robin Smith, Ben Laurens, Matthew Stratford, Richard Coles and Jonathan

Clewes,

• Jane Lloyd, Alastair Pollitt, Stuart Shaw and Neil Jones, for invaluable insights

and advice.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

3

Contents

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 2

List of tables ............................................................................................................................. 4

List of figures ........................................................................................................................... 5

Executive summary ................................................................................................................. 7

Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 13

Why look at GCSE performance and assessment standards in relation to grading severity

using CEFR descriptors ....................................................................................................... 13

Why CEFR can be considered appropriate for use in the context of GCSE MFLs in

England ................................................................................................................................ 14

Method..................................................................................................................................... 22

Overview .............................................................................................................................. 22

Specifications ....................................................................................................................... 23

Participants .......................................................................................................................... 23

Familiarisation and training .................................................................................................. 28

Content mapping .................................................................................................................. 38

Rank ordering of written and spoken performances ........................................................... 40

Standard linking of reading and listening comprehension assessments ............................ 44

Data analysis........................................................................................................................ 49

Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 53

Results .................................................................................................................................... 56

Content mapping .................................................................................................................. 56

Rank ordering of written and spoken performances to map to the CEFR .......................... 61

Standard linking of reading and listening comprehension assessments ............................ 74

Qualitative results ................................................................................................................ 88

Discussion .............................................................................................................................. 95

References ............................................................................................................................ 100

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

4

List of tables

Table 1 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish............................................................ 11

Table 2 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German............................................................ 11

Table 3 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French ............................................................. 11

Table 4 Maximum mark for specifications and papers ............................................... 23

Table 5 Breakdown of panellist background/role by panel ........................................ 23

Table 6 Breakdown of A level teacher school type and CEFR familiarity by panel .. 24

Table 7 Key features of the judging allocation design (identical for each component

and language) .............................................................................................................. 42

Table 8 CEFR levels and sub-levels used in standard linking ................................... 48

Table 9 Numerical rating scale categories – CEFR sub-levels .................................. 51

Table 10 Numerical rating scale categories - CEFR levels ........................................ 52

Table 11 Example frequency table from which cut scores are calculated ................. 52

Table 12 Content mapping ratings for productive skills ............................................. 58

Table 13 Content mapping ratings for receptive skills ............................................... 58

Table 14 Overall model fit ........................................................................................... 61

Table 15 SSR and separation coefficients ................................................................. 61

Table 16 Mark/rank order-measure correlations ........................................................ 62

Table 17 Mark points of writing scripts included in the rank ordering exercise ......... 62

Table 18 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish writing .............................................. 65

Table 19 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German writing .............................................. 66

Table 20 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French writing ................................................ 67

Table 21 Mark points of speaking scripts included in the rank ordering exercise ..... 68

Table 22 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish speaking .......................................... 70

Table 23 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German speaking .......................................... 71

Table 24 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French speaking............................................ 72

Table 25 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish productive skills .............................. 73

Table 26 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German productive skills .............................. 73

Table 27 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French productive skills ................................ 73

Table 28 ICCs based on initial ratings ........................................................................ 74

Table 29 ICCs based on final ratings .......................................................................... 74

Table 30 CEFR level rating frequency and cut scores for reading ............................ 76

Table 31 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish reading comprehension .................. 77

Table 32 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German reading comprehension .................. 78

Table 33 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French reading comprehension .................... 79

Table 34 CEFR level rating frequency and cut scores for listening ........................... 81

Table 35 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish listening comprehension ................. 82

Table 36 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German listening comprehension ................. 83

Table 37 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French listening comprehension .................. 84

Table 38 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish receptive skills ................................ 85

Table 39 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German receptive skills ................................ 85

Table 40 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French receptive skills .................................. 85

Table 41 Percentage of total marks required for each CEFR level ........................... 85

Table 42 Percentage of total marks required for each GCSE grade ......................... 86

Table 43 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish ......................................................... 96

Table 44 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German ......................................................... 96

Table 45 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French ........................................................... 96

Table 46 Indicative linking at qualification level .......................................................... 97

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

5

List of figures

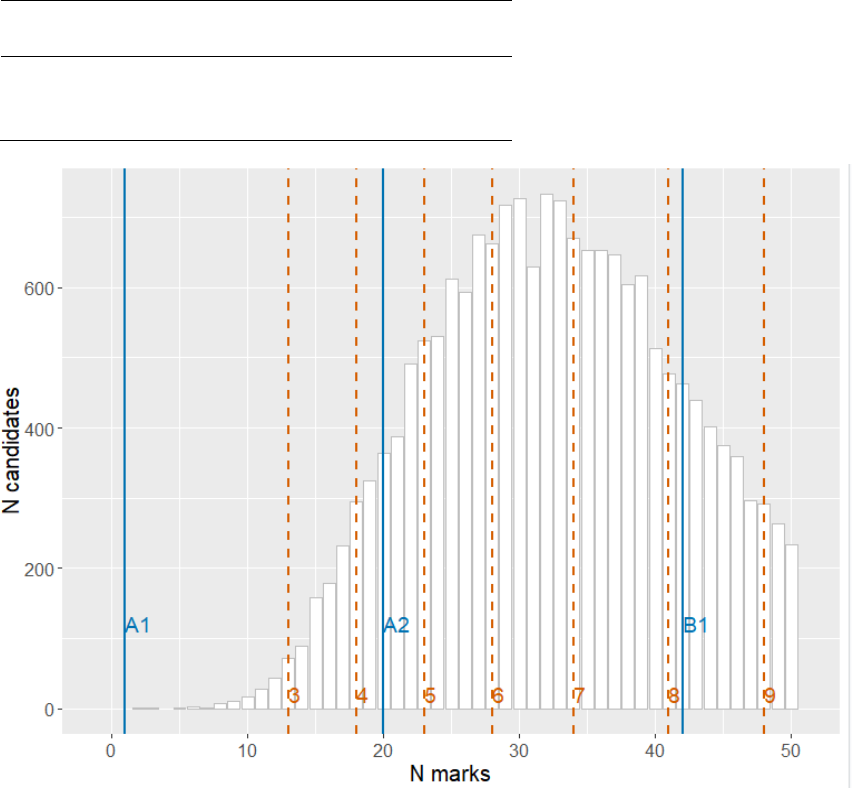

Figure 1 Estimated qualification level mapping for each language and grade .......... 12

Figure 2 The CEFR global scale ................................................................................. 15

Figure 3 The structure of the CEFR descriptive scheme ........................................... 18

Figure 4 Sequence of activities in the linking exercise............................................... 22

Figure 5 Nature of participants’ experience with the CEFR ....................................... 25

Figure 6 Participants’ attitudes to the CEFR and its use in understanding GCSE

standards ..................................................................................................................... 26

Figure 7 Experience of writing reading/listening comprehension test items and

standard setting ........................................................................................................... 27

Figure 8 Training evaluation – productive skills ......................................................... 31

Figure 9 Training evaluation – receptive skills............................................................ 32

Figure 10 Confidence in understanding the distinction between CEFR levels at the

end of the training ........................................................................................................ 33

Figure 11 Familiarisation ratings distribution of CEFR exemplars – French reading 34

Figure 12 Familiarisation ratings distribution of CEFR exemplars – French listening

..................................................................................................................................... 35

Figure 13 Familiarisation ratings distribution of CEFR exemplars – German reading

..................................................................................................................................... 36

Figure 14 Familiarisation ratings distribution of CEFR exemplars – German listening

..................................................................................................................................... 36

Figure 15 Familiarisation ratings distribution of CEFR exemplars – Spanish reading

..................................................................................................................................... 37

Figure 16 Familiarisation ratings distribution of CEFR exemplars – Spanish listening

..................................................................................................................................... 38

Figure 17 “I found rank ordering 4electronic files (writing or speaking) feasible” ...... 43

Figure 18 Example of one-mark tasks ........................................................................ 46

Figure 19 Example of a multi-mark task ..................................................................... 47

Figure 20 Spanish writing rank order - individual script measures ............................ 63

Figure 21 German writing rank order - individual script measures ............................ 64

Figure 22 French writing rank order - individual script measures .............................. 64

Figure 23 Spanish writing rank order - average grade boundary script measures ... 65

Figure 24 German writing rank order - average grade boundary script measures ... 66

Figure 25 French writing rank order - average grade boundary script measures ..... 67

Figure 26 Spanish speaking rank order - individual script measures ........................ 68

Figure 27 German speaking rank order - individual script measures ........................ 69

Figure 28 French speaking rank order - individual script measures .......................... 69

Figure 29 Spanish speaking rank order - average grade boundary script measures 70

Figure 30 German speaking rank order - average grade boundary script measures 71

Figure 31 French speaking rank order - average grade boundary script measures . 72

Figure 32 Spanish reading comprehension - distribution of CEFR sub-levels and

levels ............................................................................................................................ 75

Figure 33 German reading comprehension - distribution of CEFR sub-levels and

levels ............................................................................................................................ 76

Figure 34 French reading comprehension - distribution of CEFR sub-levels and

levels ............................................................................................................................ 76

Figure 35 Spanish reading comprehension – GCSE grade to CEFR mapping ........ 77

Figure 36 German reading comprehension – GCSE grade to CEFR mapping ........ 78

Figure 37 French reading comprehension – GCSE grade to CEFR mapping .......... 79

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

6

Figure 38 Spanish listening comprehension - distribution of CEFR sub-levels and

levels ............................................................................................................................ 80

Figure 39 German listening comprehension - distribution of CEFR sub-levels and

levels ............................................................................................................................ 80

Figure 40 French listening comprehension - distribution of CEFR sub-levels and

levels ............................................................................................................................ 81

Figure 41 Spanish listening comprehension – GCSE grade to CEFR mapping ....... 82

Figure 42 German listening comprehension – GCSE grade to CEFR mapping ....... 83

Figure 43 French listening comprehension – GCSE grade to CEFR mapping ......... 84

Figure 44 Estimated qualification level mapping for each language and grade ........ 98

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

7

Executive summary

While most stakeholders would agree that modern foreign language (MFL) study is a

valuable part of the curriculum, there is general decline in numbers of students

taking GCSEs in these subjects. There is a persistent perception that MFL GCSEs

are more difficult compared to other subjects. This is often cited as a reason for

declining subject take-up at secondary and university level. On the face of it,

consistent patterns in statistical evidence appear to support the notion that MFL

GCSEs are graded more severely than other GCSE subjects. However, while such

statistical analyses may indicate on average lower grade outcomes when controlling

for prior or concurrent attainment, these analyses do not take into account a

multitude of factors related to (perceptions of) difficulty and demand. These could be,

for instance, subject demand, nature of assessment, allocation of teaching time and

other resources, motivation of students, efficiency and effectiveness of teaching and

learning, etc. (Coe, 2008; Newton, 2012; Lockyer and Newton, 2015; Wingate, 2018;

Macaro, 2008; Graham, 2002; Klapper, 2003; etc.).

This study was part of a programme of research carried out by Ofqual to help inform

its policy decision of whether to intervene and adjust grading standards in MFL

GCSE qualifications in French, German and Spanish. The study was designed to

describe the nature of performance and assessment standards in these subjects

using the ‘metalanguage’ of the Common European Framework of Reference for

languages (CEFR), an internationally widely used framework describing language

ability via a common ‘can do’ scale, allowing broad comparisons across languages

and qualifications. The aim was to provide a platform for a more principled

discussion about whether GCSE MFL performance standards and corresponding

grading standards are appropriate for these qualifications, or are indeed too high.

We do not believe that possible discrepancies between the notions of communicative

language competence and language use as described in the CEFR, and the way

communicative language competence and use may be understood, taught, and

assessed at GCSE level, would in itself invalidate an attempt to describe GCSE

MFLs in terms of CEFR descriptors. We would argue that, as long as the broad

intention of the MFL GCSE curriculum and pedagogy is reasonably aligned to the

CEFR – and this would appear to be the case as, for instance, MFL GCSEs should

“develop [learners’] ability to communicate confidently and coherently with native

speakers in speech and writing, conveying what they want to say with increasing

accuracy” (DFE, 2015: 3) – a description in terms of the CEFR may not only be

appropriate, but also helpful.

However, we do believe that it is important to be aware of the specific context of the

MFL GCSEs, as it may account for occasional disjoint between CEFR descriptors

and GCSE assessments/performances that are observed in the linking. In addition,

an awareness of these discrepancies could be helpful for improving both current

language pedagogy and assessment methods where appropriate, helping learners to

achieve the goal of communicative language competence at the level appropriate for

the phase of education at which they are.

Because this study was designed as a piece of research to answer a specific

research question, rather than as a full-blown linking study, it consequently has

some potential limitations in scope and generalisability. This is, to our knowledge,

the first explicit attempt to link GCSE MFL qualifications to the CEFR using

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

8

recommended methodology, and so we consider this study primarily exploratory.

Involvement and endorsement of other relevant stakeholders (e.g. Department for

Education, exam boards), greater resources, further refinement of some aspects of

the methodology and linking of specifications from other exam boards would be

necessary to conduct a linking study where the results might be considered to

represent an “official” linking. Therefore, the findings need to be treated as

essentially descriptive and indicative. Having said this, we have made every effort to

conduct this linking study according to best practice in the field, and in this sense,

the results should be reasonably robust for those specifications on which the linking

was performed.

In this study, key grades (grades 9, 7 and 4) in GCSE French, German and Spanish

on the summer 2018 tests were notionally linked to the CEFR scale. Initially, content

mapping (i.e., relating the construct and content coverage of the GCSE to the CEFR)

was carried out for each subject by a CEFR expert and a GCSE subject expert.

Subsequently, panels of 13 experts (including CEFR experts, Higher Education and

subject experts, A level teachers and exam board representatives) carried out the

following activities for each subject:

• For writing and speaking, they rank ordered, in terms of overall quality, series

of GCSE performances (at grades 9, 7 and 4) interspersed with performances

previously independently benchmarked on the CEFR scale. This created an

overall performance quality scale on which the relative position of the GCSE

and CEFR performances was determined, and CEFR-related performance

standards at grades 9, 7 and 4 extrapolated from this.

• For reading and listening comprehension, they conducted a ‘standard linking’

exercise using the ‘Basket Method’ to rate each mark point on the tests in

terms of the CEFR levels. CEFR level cut scores were derived from these

ratings and grades 9, 7 and 4 related to these in terms of proportions of marks

on the test needed to achieve each.

• The linking results at component level were averaged to get a

qualification-level estimate of the mapping of each grade to the CEFR level.

The results of the linking at component level are shown in Tables 1 to 3 . The linking

of GCSE grades to the CEFR levels across components within Spanish and German

is very consistent, with productive skills being at a lower CEFR level than the

receptive skills. French mapping is less consistent, but this may be partly due to the

issues with the CEFR exemplars for productive skills, and apparent issues with the

listening comprehension paper (described in the Results section). Therefore, we

would suggest that the linking for French is more tentative than for the other two

languages. The patterns are broadly consistent across the 3 languages, with the

notable exception of grade 7 for productive skills (lowest standard in Spanish), and

grade 4 for receptive skills (highest standard in Spanish).

Figure 1 shows indicative linking at qualification level for each grade, based on

averaging across the CEFR sub-levels of components. It appears that performance

standards between the 3 languages are reasonably aligned at qualification level

despite some component-level inconsistencies. The results suggest that grade 4 is

around high A1 level for Spanish and mid A1 level for German and French. Grade 7

is around mid A2 level and grade 9 around low B1 for all languages. This result

accords with the results of the content mapping, which suggested that each of the 3

GCSE MFL specifications assessed most of the skills up to A2+ (i.e. high A2) level,

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

9

with some aspects of language competence assessed up to low B1 level. While a

degree of consistency across languages is perhaps to be expected given that these

assessments are supposed to be developed based on specifications that should be

reasonably aligned in terms of content and implicit demand, there is no particular

reason why we should expect the performance standards for different grades to be

perfectly aligned across languages. This reminds us that considering standards

between even quite related subjects involves considerable nuance and

interpretation.

However, in addition to the limitations discussed in the Limitations section, an

important “health warning” regarding the interpretation of this linking is in order. It

should be borne in mind that the limitations of assessments highlighted in both

content mapping and in discussion with panellists, particularly with respect to

assessment of interaction and integrated skills, would to some extent limit the

interpretation based on these assessments that candidates are fully at A2 or B1

level. This is because the assessments themselves provide little evidence of some of

the skills essential for communicative language competence, such as ability to

engage in meaningful interaction. In a sense, it may be more appropriate to say that,

overall, candidates achieving each of the GCSE grades possess most, but not all, of

the skills and knowledge required of the CEFR level assigned in this linking exercise.

While this is also true of A2 level to some extent, most of the caveats and

discrepancies relate to where assessments appear to be targeting B1 level, as in

many cases assessments were patchy in the extent to which they allowed for all of

the skills relevant for B1 level to be demonstrated. This would mean that the levels

assigned to different grades could be seen as overestimates to some extent,

particularly for B1 level, but also to some extent for A2. This should be borne in mind

in any discussions about whether A2 or B1 level may be appropriate for different

GCSE grades.

This linking study dealt with describing the content/construct of GCSE MFL

specifications and tests, as well as performances, in terms of the CEFR, and relating

the current GCSE grading standards to the CEFR. The results essentially give an

indication of where GCSE assessments are pitched and which performance

standards are represented by different GCSE grades, using the language of the

CEFR descriptors. Therefore, this linking is not a statement of what the GCSE

standard should be, but an approximate description of what the performance and

assessment/grading standard currently appears to be, using the language and

descriptors of the CEFR.

The GCSE MFL assessments reviewed in this study do not appear to elicit sufficient

evidence of certain linguistic skills that may be considered by some to be a crucial

part of communicative language competence. It would seem important to investigate

these issues further and explore ways in which the assessments might be made

more effective in assessing these important skills. As far as GCSE MFLs should

enable learners to act in real-life situations, expressing themselves and

accomplishing tasks of different natures, it would make sense that, like the CEFR,

they put the co-construction of meaning (through interaction) at the centre of the

learning and assessment process.

The results are offered to stakeholders for consideration as to whether the content

and performance standards and assessment demands associated with the key

GCSE grades are appropriate given the purpose of GCSE qualifications, the spirit

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

10

and nature of the curriculum, and the current context of GCSE MFL learning and

teaching. For instance, if the relevant stakeholders were to conclude that, generally

speaking, a mid A2 level of performance is too high for GCSE grade 7, this could

provide rationale to support a change to grading standards. However, in this case,

this rationale would not be based on statistical evidence or any notions of

comparable ‘value-added’ between different subjects, but based on an

understanding of what an appropriate performance standard, in terms of what

students can do, is or should be for each grade within MFLs themselves.

We would suggest, however, in the spirit of the CEFR, that discussions around the

appropriateness of language performance and assessment standards should

consider important aspects of the context of language teaching in schools. The

CEFR (Council of Europe, 2018: 28) suggests planning backwards from learners’

real life communicative needs, with consequent alignment between curriculum,

teaching and assessment. As North (2007a) points out, educational standards must

always take account of the needs and abilities of the learners in the context

concerned. Norms of performance need to be definitions of performance that can

realistically be expected, rather than relating standards to “some neat and tidy

intuitive ideal” (Clark 1987: 46). This posits an empirical basis to the definition of

standards. If used appropriately, the CEFR could aid this endeavour in the context of

GCSE MFLs in England.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of the CEFR

11

Table 1 GCSE to CEFR mapping for Spanish

Writing

Speaking

Reading

Listening

GCSE

grade

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

4

Mid-high

A1

A1

Low-mid

A1

A1

Low-mid

A2

A2

Low-mid

A2

A2

7

Low-mid

A2

A2

Low-mid

A2

A2

Mid-high

A2

A2

Mid-high

A2

A2

9

Low-mid

B1

B1

Low-mid

B1

B1

Low-mid

B1

B1

Low-mid

B1

B1

Table 2 GCSE to CEFR mapping for German

Writing

Speaking

Reading

Listening

GCSE

grade

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

4

Low-mid

A1

A1

Mid A1

A1

High A1-

low A2

A1/A2

High A1-

low A2

A1/A2

7

Mid-high

A2

A2

High A2

A2

Mid-high

A2

A2

Mid-high

A2

A2

9

Low-mid

B1

B1

Low B1

B1

Low-mid

B1

B1

Low-mid

B1

B1

Table 3 GCSE to CEFR mapping for French

Writing

Speaking

Reading

Listening

GCSE

grade

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

CEFR

sub-level

CEFR

level

4

High A1-

Low A2

A1/2

Low-mid

A1

A1

High A1-

low A2

A1/A2

Low-mid

A1

A1

7

Low-mid

B1

B1

High A2-

low B1

A2/B1

Mid-high

A2

A2

High A1-

low A2

A1/A2

9

Low-mid

B1

B1

Mid-high

B1

B1

Low-mid

B1

B1

High A2-

lowB1

A2/B1

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

12

PROFICIENT USER

C2

Can understand with ease virtually everything heard or

read. Can summarise information from different spoken

and written sources, reconstructing arguments and

accounts in a coherent presentation. Can express

him/herself spontaneously, very fluently and precisely,

differentiating finer shades of meaning even in more

complex situations.

C1

Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer

texts, and recognise implicit meaning. Can express

him/herself fluently and spontaneously without much

obvious searching for expressions. Can use language

flexibly and effectively for social, academic and

professional purposes. Can produce clear, well-

structured, detailed text on complex subjects, showing

controlled use of organisational patterns, connectors

and cohesive devices.

INDEPENDENT USER

B2

Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both

concrete and abstract topics, including technical

discussions in his/her field of specialisation. Can

interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that

makes regular interaction with native speakers quite

possible without strain for either party. Can produce

clear, detailed text on a wide range of subjects and

explain a viewpoint on a topical issue giving the

advantages and disadvantages of various options.

B1

Can understand the main points of clear standard input

on familiar matters regularly encountered in work,

school, leisure, etc. Can deal with most situations likely

to arise whilst travelling in an area where the language

is spoken. Can produce simple connected text on topics

which are familiar or of personal interest. Can describe

experiences and events, dreams, hopes and ambitions

and briefly give reasons and explanations for opinions

and plans.

BASIC USER

A2

Can understand sentences and frequently used

expressions related to areas of

most immediate relevance (e.g. very basic personal

and family information, shopping, local geography,

employment). Can communicate in simple and routine

tasks requiring a simple and direct exchange of

information on familiar and routine matters. Can

describe in simple terms aspects of his/her background,

immediate environment and matters in areas of

immediate need.

A1

Can understand and use familiar everyday expressions

and very basic phrases aimed at the satisfaction of

needs of a concrete type. Can introduce him/herself

and others and can ask and answer questions about

personal details such as where he/she lives, people

he/she knows and things he/she has. Can interact in a

simple way provided the other person talks slowly and

clearly and is prepared to help.

Figure 1 Estimated qualification level mapping for each language and grade

S 4

S 7

G 4

G 7

F 4

F 7

S 9

G 9

F 9

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

13

Introduction

While most stakeholders would agree that modern foreign language (MFL) study is a

valuable part of the curriculum, there is general decline in numbers of students

taking GCSEs in these subjects. There is a persistent perception that MFL GCSEs

are more difficult compared to other subjects. This is often cited as a reason for

declining subject take-up at secondary and university level.

On the face of it, consistent patterns in statistical evidence appear to support the

notion that MFL GCSEs are graded more severely than other GCSE subjects.

However, while statistical analyses may indicate on average lower grade outcomes

when controlling for prior or concurrent attainment, these analyses do not take into

account a multitude of factors related to (perceptions of) difficulty and demand.

These could be, for instance, subject demand, nature of assessment, allocation of

teaching time and other resources, motivation of students, efficiency and

effectiveness of teaching and learning, etc. (Coe, 2008; Newton, 2012; Lockyer and

Newton, 2015; Cuff, 2017; Wingate, 2018; Macaro, 2008; Graham, 2002; Klapper,

2003; etc.).

This study was part of a programme of research carried out by Ofqual to help inform

its policy decision of whether to intervene and adjust grading standards in MFL

GCSE qualifications in French, German and Spanish. The study was designed to

describe the nature of performance and assessment standards in these subjects

using the ‘metalanguage’ of the Common European Framework of Reference for

languages (CEFR), an internationally widely used framework describing language

ability via a common ‘can do’ scale, allowing broad comparisons across languages

and qualifications. The aim was to provide a platform for a more principled

discussion about whether GCSE MFL performance standards and corresponding

grading standards are appropriate for these qualifications, or are indeed too high.

Why look at GCSE performance and assessment

standards in relation to grading severity using CEFR

descriptors

The assessment instruments and test specifications interpret GCSE MFL standards

in a particular way, by including certain curriculum domains, assessment methods,

marking criteria and questions of varying types and demand, guided by Department

for Education subject content (DfE, 2015) and guidelines about desirable features of

assessments. However, in the absence of clear and sufficiently detailed performance

descriptors for different grades, it is difficult to establish whether these assessments

are appropriately ‘pitched’ to test at appropriate and agreed level.

1

Currently, as in other GCSEs, the grading standard of GCSE MFLs is maintained

using the comparable outcomes approach, which maintains the ‘value-added’

1

Before the reformed GCSEs were sat for the first time, Ofqual, working with subject experts and

senior examiners from exam boards, developed grade descriptions for grade 8, 5 and 2.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/grade-descriptors-for-gcses-graded-9-to-1

The aim of these grade descriptions was to give teachers an indication of the likely level of

performance. They were not intended to be used to set standards in the first new awards, and the

intention was to review them once the new qualifications had settled down.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

14

relationship for the cohort between Key stage 2 and GCSE. However, there is little

clarity as to what it is that students at different GCSE grades should be able to do, or

can actually do with language. It is also difficult to say whether GCSE assessments

themselves are pitched at an appropriate level of demand, as it is not universally

understood or accepted amongst stakeholders what is actually an appropriate or

realistic level of demand for this qualification and individual grades. Furthermore,

there is a lack of clarity with respect to what different stakeholders might consider to

be appropriate requirements and performance standards for different GCSE grades

(cf. the results of stakeholder surveys presented in Curcin and Black, 2019). Part of

this lack of clarity is probably due to the difficulties associated with articulating

performance standards in the first place.

This is primarily what our study tried to establish – where GCSE assessments are

pitched and what performance standards are represented by different GCSE grades.

A very useful and well-established tool for articulating performance standards in

languages is the CEFR. This framework is intended to provide a ‘universal’

metalanguage for description of language competence. Once we understand which

performance standards that are expected at different grades, we can then discuss

whether that level is appropriate for the current context of GCSE MFL learning and

teaching, given the spirit and nature of the curriculum, for different purposes of

GCSEs, for different stakeholders, etc.

We are conscious that, while the CEFR is intended to provide a metalanguage for

description of language competence, it is not intended to be used indiscriminately

and without regard to local context and local educational aims (see below for more

details on this). In this study, we took care to acknowledge the limitations of the

CEFR application to the context of GSCE assessments, for instance where GCSE

underspecifies certain aspects of linguistic competence at some CEFR levels, while

fully according with other aspects. These will be clearly pointed out and relevant

caveats highlighted in reporting the results of our linking and in any further

discussions regarding the appropriate performance standards for GCSE MFLs.

It is important to emphasise that this study dealt with describing the content/construct

of GCSE MFL specifications and tests, as well as performances, in terms of the

CEFR, and relating current GCSE grading standards to the CEFR. This study is not

a statement of what the standard should be, but an approximate description of what

the performance and assessment/grading standard currently appears to be, using

the language and descriptors of the CEFR.

Furthermore, we should emphasise that the GCSE to CEFR ‘linking’ attempted in

this study can be considered exploratory and preliminary, rather than as an ‘official’

linking, being limited in scope to a subset of the relevant specifications. This was a

research exercise, carried out to facilitate a resolution of the debates around grading

severity, rather than with official linking as its main goal. Methodological and other

limitations are discussed at some length in the Limitations section and in the

Discussion.

Why CEFR can be considered appropriate for use in

the context of GCSE MFLs in England

The CEFR aims to describe what students can do with language (any [European]

language, not just English) at different competence levels, across 6 levels of

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

15

proficiency spanning from A1 (Basic User – ‘Breakthrough’) to C2 (Proficient User –

‘Mastery’) – see Figure 2. CEFR descriptors were initially developed in a multi-lingual

environment, and in relation to 3 foreign languages (English, French, German)

(North, 1998, 2007a, 2007b)

2

rather than solely with reference to English as the

second language. Furthermore, they assume the cognitive and social competences

of young adults at age 16 and above, and are thus age-appropriate for use in the

context of GCSEs.

PROFICIENT USER

C2

Can understand with ease virtually everything heard or read. Can

summarise information from different spoken and written sources,

reconstructing arguments and accounts in a coherent presentation. Can

express him/herself spontaneously, very fluently and precisely,

differentiating finer shades of meaning even in more complex situations.

C1

Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer texts, and recognise

implicit meaning. Can express him/herself fluently and spontaneously

without much obvious searching for expressions. Can use language flexibly

and effectively for social, academic and professional purposes. Can

produce clear, well-structured, detailed text on complex subjects, showing

controlled use of organisational patterns, connectors and cohesive devices.

INDEPENDENT USER

B2

Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and

abstract topics, including technical discussions in his/her field of

specialisation. Can interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that

makes regular interaction with native speakers quite possible without strain

for either party. Can produce clear, detailed text on a wide range of subjects

and explain a viewpoint on a topical issue giving the advantages and

disadvantages of various options.

B1

Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters

regularly encountered in work, school, leisure, etc. Can deal with most

situations likely to arise whilst travelling in an area where the language is

spoken. Can produce simple connected text on topics which are familiar or

of personal interest. Can describe experiences and events, dreams, hopes

and ambitions and briefly give reasons and explanations for opinions and

plans.

BASIC USER

A2

Can understand sentences and frequently used expressions related to

areas of most immediate relevance (e.g. very basic personal and family

information, shopping, local geography, employment). Can communicate in

simple and routine tasks requiring a simple and direct exchange of

information on familiar and routine matters. Can describe in simple terms

aspects of his/her background, immediate environment and matters in areas

of immediate need.

A1

Can understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic

phrases aimed at the satisfaction of needs of a concrete type. Can introduce

him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions about personal

details such as where he/she lives, people he/she knows and things he/she

has. Can interact in a simple way provided the other person talks slowly and

clearly and is prepared to help.

Figure 2 The CEFR global scale

According to the CEFR document (Council of Europe, 2001), the CEFR does not

inherently impose any standards on the local context. It is a descriptive tool and is

intended to provide a shared basis for reflection and communication among those

involved in teacher education and in the elaboration of language syllabuses,

2

See Appendix A for a brief summary of the history of the CEFR and the development of its

descriptor scales.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

16

curriculum guidelines, textbooks, examinations, etc., across different countries and

educational systems. It should allow users to reflect on their decisions and practice,

and to situate and co-ordinate their efforts, as appropriate, for the benefit of

language learners in their specific contexts. It is a flexible tool to be adapted to the

specific context of use.

North (2007a) points out that there is no need for a conflict between using a common

framework such as the CEFR to provide transparency and coherence and the need

to have local strategies that provide learning goals specific to particular contexts.

The main danger is a simplistic interpretation of the common framework. The key to

its valid use is for users to appreciate that a common framework is a descriptive

metasystem that is intended as a reference point, not as a tool to be implemented

without further elaboration and adaptation to local circumstances (see also, e.g.

Taylor, 2004). According to North (2007b), the idea is for users to divide or merge

activities, competences, and proficiency stepping-stones, as described in the CEFR,

that are appropriate to their local context. The use of CEFR descriptors allows these

to be related to the greater scheme of things and thus communicated more easily to

colleagues in other educational institutions and, in simplified form, to other

stakeholders.

Since its launch in 2001, the CEFR has been translated into approximately 30

languages. It has become the most commonly referenced document upon which

language teaching and assessment has come to be based, both in Europe and

internationally (O’Sullivan, 2015). An example of its international use is in Taiwan

(Wu & Wu, 2010, p. 205), where all nationally recognised examinations must

demonstrate a link to the CEFR. Other examples of linking for a range of different

languages and tests include: Dutch foreign language state examinations (French,

German and English as foreign languages); Asset languages in England; Certificate

of Italian as a Foreign language; European Consortium for the Certificate of

Attainment in Modern Languages (ECL) tests of German, English and Hungarian as

foreign languages; Test of German as a Foreign Language (TestDaF); the City &

Guilds Communicator examination, etc. (all presented in Martyniuk, W. (ed.), 2010).

Furthermore, UK Quality Code for Higher Education (2015: 7) acknowledges that the

CEFR has become the predominant international standard, and the Subject

Benchmark Statement in this document attempts to adopt the CEFR as appropriate

to UK higher education, advocating its use as a benchmark for standards of

achievement at different levels in university language learning programmes (ibid.:

22). A number of university MFL departments and university language centres in

England have either explicitly mapped their courses to the CEFR or make reference

to the CEFR in describing the achievement levels of their students at the end of their

courses.

3

3

https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/clas/documents/language-achievement-levels.pdf

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/courses/modern-languages-ba-hons-r800/#structure

https://www.city.ac.uk/study/courses/short-courses/modern-languages

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/modernlanguages/intranet/undergraduate/courseoutlines/r9q1/faq/

http://www.open.ac.uk/courses/qualifications/q30

https://www.york.ac.uk/lfa/courses/long/

http://www.bristol.ac.uk/sml/study/uwlp/

https://www.kcl.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/courses/german-with-a-year-abroad-ba

https://www.brookes.ac.uk/courses/undergraduate/applied-languages

https://www.langcen.cam.ac.uk/culp/culp-general-courses.html

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

17

According to the CEFR document (Council of Europe, 2001), the CEFR

comprehensively describes what language learners have to do in order to use a

language for communication and what knowledge and skills they have to develop so

as to be able to act effectively in that language. The description also covers the

cultural context in which language is set. The CEFR also defines levels of proficiency

which allow learners’ progress to be measured at each stage of learning. According

to the CEFR, any form of language use and learning could be described as follows

(Council of Europe, 2001: 9):

Language use, embracing language learning, comprises the actions

performed by persons who as individuals and as social agents

develop a range of competences, both general and in particular

communicative language competences. They draw on the

competences at their disposal in various contexts under various

conditions and under various constraints to engage in language

activities involving language processes to produce and/or receive

texts in relation to themes in specific domains, activating those

strategies which seem most appropriate for carrying out the tasks

to be accomplished. The monitoring of these actions by the

participants leads to the reinforcement or modification of their

competences.

Communicative language competence can be considered as comprising 3 key

components: linguistic, sociolinguistic and pragmatic. Each of these components is

postulated as comprising knowledge and skills and know-how. The language

learner/user’s communicative language competence is activated in the performance

of the various language activities, involving reception, production,

4

interaction

5

or

mediation

6

(in particular interpreting or translating). Each of these types of activity is

possible in relation to texts in oral or written form, or both. This is summarised in

Figure 3:

4

The skills of writing and speaking are usually referred to as productive skills or production. The skills

of listening and reading comprehension are usually referred to as receptive skills or reception.

5

According to Council of Europe (2018: 81), Interaction, which involves 2 or more parties

co-constructing discourse, is central in the CEFR scheme of language use. Spoken interaction is

considered to be the origin of language, with interpersonal, collaborative and transactional functions.

Interaction is also seen as fundamental in learning. The CEFR scales for interaction strategies reflect

this with scales for turn-taking, cooperating (collaborative strategies) and asking for clarification.

6

According to the CEFR text (ibid.: 14), written or oral mediation makes communication possible

between persons who are unable to communicate with each other directly. Translation or

interpretation, a paraphrase, summary or record, provides for a third party a (re)formulation of a

source text to which this third party does not have direct access. The Council of Europe (2018: 103),

expands on this definition to state that in mediation, the user/learner acts as a social agent who

creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning, sometimes within the same language,

sometimes from one language to another (cross-linguistic mediation). The focus is on the role of

language in processes like creating the space and conditions for communicating and/or learning,

collaborating to construct new meaning, encouraging others to construct or understand new meaning,

and passing on new information in an appropriate form. The context can be social, pedagogic,

cultural, linguistic or professional.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

18

Figure 3 The structure of the CEFR descriptive scheme

7

According to Council of Europe (2018: 28), such a view of the language learner and

the language use and learning accords with the approach to teaching and learning

suggested by the CEFR, which is that language learning should be directed towards

enabling learners to act in real-life situations, expressing themselves and

accomplishing tasks of different natures. It implies that the teaching and learning

process is driven by action, that it is action-oriented. It also suggests planning

backwards from learners’ real life communicative needs, with consequent alignment

between curriculum, teaching and assessment. Both the CEFR descriptive scheme

and the action-oriented approach put the co-construction of meaning (through

interaction) at the centre of the learning and teaching process.

The CEFR scheme is compatible with several approaches to second language

learning, including the task-based approach (also known as communicative

language teaching approach, CLT) (Council of Europe, 2018: 30). The CLT

approach emphasises meaning-focused interaction in the target language, the

choice of topics and activities that resemble real-life communication, the use of

authentic texts and tasks, and a focus on the learning process itself (e.g. Wingate,

2018; cf. Nunan 1991; Mitchell 1994; Sauvignon, 2000). Aspects of the

communicative approach appear to be suggested in the GCSE MFL curriculum

(DFE, 2015) and used in GCSE MFL teaching (e.g. Bauckham, 2018; Wingate,

2018) although it is not entirely clear whether this is the dominant approach in all

MFL classrooms in England.

Wingate (2018: 443) gives a useful history and summary of the curriculum and

teaching approach in England in KS3 and KS4. Since MFL was included in 1992 as

7

Taken from Council of Europe (2018: 30).

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

19

a foundation subject in the new National Curriculum (NC) framework for KS3 and

KS4, the first policy document of the National Curriculum for Modern Foreign

Languages (DES/WO 1991), as well as its subsequent versions, followed the CLT

approach. According to this author, although CLT was not explicitly mentioned in the

NC documents, this orientation was obvious in the educational purposes stated in

the original policy document, and in the associated Programme of Study (PoS). The

first of 8 educational purposes is ‘to develop the ability to use the language

effectively for purposes of practical communication’ (DES/WO 1990: 3). Wingate

cites Mitchell (2003: 18), who explains in reference to the 1999 version of the NC,

that the PoS ‘clearly encourage maximising learners’ involvement in meaningful

target language use’.

The new Department for Education subject content for reformed GCSE MFLs (DfE,

ibid.: 3) lists the following as subject aims and learning outcomes, which should

enable students to:

• develop their ability to communicate confidently and coherently with native

speakers in speech and writing, conveying what they want to say with

increasing accuracy

• express and develop thoughts and ideas spontaneously and fluently

• listen to and understand clearly articulated, standard speech at near normal

speed

• deepen their knowledge about how language works and enrich their

vocabulary in order for them to increase their independent use and

understanding of extended language in a wide range of contexts

• acquire new knowledge, skills and ways of thinking through the ability to

understand and respond to a rich range of authentic spoken and written

material, adapted and abridged, as appropriate, including literary texts

• develop awareness and understanding of the culture and identity of the

countries and communities where the language is spoken

• be encouraged to make appropriate links to other areas of the curriculum to

enable bilingual and deeper learning, where the language may become a

medium for constructing and applying knowledge

• develop language learning skills both for immediate use and to prepare them

for further language study and use in school, higher education or in

employment

• develop language strategies, including repair strategies

As with the previous versions of the NC, achievement of these goals would suggest

development of communicative language competence, as well as use of the CLT

approach. Therefore, the pedagogy of GCSE MFLs, and the approach in their

associated assessments, should be compatible with the CEFR view of the language

learner and language learning process, and thus not preclude a description of GCSE

MFL performance standards and assessment standards in terms of the CEFR.

It should be noted, however, that available research suggests that current teaching

methodologies at KS3 and KS4 may not be implementing the CLT approach in the

way it was intended (e.g. Wingate, 2018, Bauckham, 2016). According to Bock

(2002: 20, cited in Wingate, ibid.) the adaptation of CLT approach in the National

curriculum for MFL has been accused of representing a narrow understanding of

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

20

communicative competence and drawing ‘on a rather selective interpretation’ of the

original principles (Block 2002: 20). This ‘partial’ and ‘rather simplified version’ (ibid.)

has been blamed for over-emphasising speaking drills while at the same time failing

to develop linguistic competence (Klapper 1997, 1998; Meiring and Norman 2001),

knowledge about language, learner autonomy and intercultural competence (Pachler

2000). Mitchell and Martin (1997: 23) found in a study of French lessons in English

secondary schools that ‘learners were explicitly taught a curriculum consisting very

largely of unanalysed phrases’ which were ‘memorised and rehearsed unaltered’.

According to Wingate (ibid.), some of this may be related to misconceptions about

CLT in its strong version (cf. Swan, 1985) that instructed foreign language learning

works in the same way as first language acquisition, and that learners would acquire

grammatical structures implicitly from target language input. At the time of the NC’s

implementation, second language acquisition theory had recognised the need for

‘focus on form’ (Long 1991) alongside the focus on meaning (Wingate, ibid.: 444).

Based on a small-scale study in KS3 context, Wingate (ibid.) suggests that the

teaching practices may now have shifted from the earlier CLT-orientation and may

currently be dictated by the attainment targets that demand grammatical accuracy.

While it is unclear whether a similar situation pertains to KS4 classrooms currently

(although there are suggestions that this may be so, see Bauckham, 2016b), we

believe it is important to bear in mind these indicators that MFL pedagogy in England

may not be following the practices most widely recommended internationally.

8

We do not believe that possible discrepancies between the notions of communicative

language competence and language use as described in the CEFR, and the way

communicative language competence and use may be understood, taught, and

assessed at GCSE level in itself would invalidate an attempt to describe GCSE

MFLs in terms of CEFR descriptors. We would argue that as long as the broad

intention of the GCSE MFL curriculum and pedagogy is reasonably aligned to the

CEFR – and this would appear to be the case as, for instance, they should “develop

[learners’] ability to communicate confidently and coherently with native speakers in

speech and writing, conveying what they want to say with increasing accuracy” – a

description in terms of the CEFR may not only be appropriate, but also helpful.

However, we do believe that it is important to be aware of this context, as it may

account for occasional disjoint between CEFR descriptors and GCSE

assessments/performances that are observed in the linking. In addition, an

awareness of these discrepancies could be helpful for improving both current

8

Wingate (ibid.: 444) notes that although CLT has generally been regarded as an approach that

motivates learners because it offers topic relevance and learner choice, current research suggests

that this may not be the case with the in MFL classrooms in England. Various motivation studies

carried out in the first ten years since the inception of the NCMFL (e.g. Chambers 1999; Graham

2002) revealed that MFL was the least popular subject and pupils found language lessons boring and

repetitive. As Mitchell (2000: 288) explained, ‘the curriculum may be too narrowly focused on

pragmatic communicative goals, so that insufficient educational challenge is offered, with negative

impact on pupil motivation’. Bartram (2005) found that pupils’ attitudes towards learning French were

negative because their use of language was limited to specific phrases prescribed for narrow

communicative situations. In a review of the situation of language learning in English schools,

commissioned by the government, Dearing and King (2007) criticised the lack of engaging curricular

content and the fact that ‘the present GCSE does not facilitate discussion, debates and writing about

subjects that are of concern and interest to teenagers’. Macaro (2008) argued that many pupils lose

motivation early on in KS3, because they are aware of a lack of progress and their inability to interact

in the target language.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

21

language pedagogy and assessment methods where appropriate, helping learners to

achieve the goal of communicative language competence at the level appropriate for

the phase of education at which they are.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

22

Method

Overview

The approach in this study was guided by the recommended methods and

procedures in the manual for relating language examination to the CEFR (Council of

Europe, 2009) (henceforth, the Manual), and the updated descriptors from the

companion volume (Council of Europe, 2018). The study was designed to provide

empirical evidence for a link between performance and assessment standards of

French, German and Spanish GCSE assessments at grades 9, 7 and 4, and the

CEFR.

9

Following the Manual, the study involved 5 stages:

1. familiarisation/training of participants,

2. content mapping (i.e., specification or relating the construct/content of the

GCSE to the CEFR),

3. linking of performance standards for productive skills,

4. linking of assessment standards for receptive skills (including additional

training/standardisation), and

5. empirical validation and evaluation.

Taken together, the results of stages 2-5 above should provide an indication of how

GCSE performance and grading standards relate to the CEFR and its set of “can do”

descriptors.

The figure below shows the sequence of key activities in the linking exercise. Each

of the activities is described separately in more detail in the following sections.

Figure 4 Sequence of activities in the linking exercise

9

Note that work from higher tier only was considered for grade 4.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

23

Specifications

Three specifications with larger entries from 2 exam boards were chosen for the

study:

• AQA GCSE French (8658)

• AQA GCSE German (8668)

• Pearson GCSE Spanish (1SP0)

All of these were new, reformed GCSE specifications developed for first assessment

in summer 2018. Therefore, only assessment materials from the June 2018

examination session were available for the study. Only work from the higher tier was

considered for grade 4. The table below shows maximum marks for each

specification and paper.

Table 4 Maximum mark for specifications and papers

Specification

Writing

Speaking

Reading

Listening

Total

French

60

60

60

50

230

German

60

60

60

50

230

Spanish

60

70

50

50

230

Participants

For each language, panels of 13 experts were recruited to participate. We

endeavoured to recruit participants who had at least some familiarity with the CEFR.

However, this was not possible in all cases. Nevertheless, the majority of the

participants did have some relevant CEFR experience.

Each of the 3 panels consisted of: HE linguists, staff from international testing

organisations (Institut Francais, Alliance Français, Goethe Institut and Instituto

Cervantes), and Ofqual subject experts, all with reasonable experience or specialism

in the CEFR; A level MFL teachers from both state and independent schools, most

with some familiarity with the CEFR; representatives of subject associations; and

representatives of exam boards. The participants from the last 2 groups did not

necessarily have direct experience of using the CEFR.

Table 5 Breakdown of panellist background/role by panel

Role

French

German

Spanish

HE experts

3

5

5

International testing

organisations experts

3

1

1

A level teachers

4

4

4

Ofqual subject experts

1

1

1

Subject association reps

1

1

1

Examination board reps

1

1

1

HE participants were recruited via contacts collated for a previous study (Curcin and

Black, 2018). On this occasion, however, participation was conditional on practical

experience with the CEFR.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

24

The participants from international testing organisations were contacted via

institutional email addresses in the first instance. The relevant institutions then chose

the most suitable person with relevant CEFR experience, who took part in the study.

A level teachers were recruited by initially contacting administration offices of all

state and independent secondary schools with more than 10 A level candidates in

2018. Again, participation ideally required some degree of familiarity with the CEFR.

Table 6 Breakdown of A level teacher school type and CEFR familiarity by panel

Panel

Participant ID

School type

CEFR familiarity

French

J05

Sixth Form College

N

J07

Grammar school

Y

J31

Academy

Y

J33

Independent

Y

German

J04

Independent

Y

J08

Academy

Y

J12

Grammar school

Y

J13

Sixth Form College

N

Spanish

J03

Grammar school

Y

J10

Grammar school

Y

J15

Sixth Form College

Y

J16

Independent

Y

Ofqual subject experts were recruited by sending invitations to participate to all

experts on the Ofqual list with relevant subject expertise. One of the requirements for

participation was a reasonable practical experience of using the CEFR.

Subject associations and exam boards were invited to send a representative for

each language, where possible with some familiarity with the CEFR. The

representatives of exam boards were either examiners or subject experts. They were

allocated to panels such that the representatives came from a different exam board

from that whose specification was the focus of the panel. Thus, a WJEC

representative attended the French panel, a Pearson representative attended the

German panel, and an AQA representative attended the Spanish panel.

At the start of their online familiarisation, the participants were asked several

questions about their experience of and attitudes towards the CEFR. Figure 5 shows

a breakdown of participant CEFR familiarity levels prior to familiarisation by panel.

The charts show a similar pattern across the 3 languages, with the majority of the

participants having an interest in the CEFR, some theoretical or academic

knowledge of it and some practical experience of using it in the context of teaching

and marking. Over half of the participants in each panel had some experience of

using the CEFR in the test or resource development. Except for the Spanish panel,

few participants had experience of using the CEFR in the context of teaching English

as a foreign language, while the majority in every panel had experience of using it in

the context of teaching the target language of the panel as a foreign language. One

or 2 participants had experience of the CEFR solely based on teaching English as a

foreign language.

Figure 6 shows participants’ attitudes towards the CEFR for each panel. With very

few exceptions, the participants either strongly agreed or agreed with the way the

CEFR describes differences in learner ability levels. Similar attitude was expressed

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

25

towards the statement that understanding GCSE standards in relation to the CEFR

may be helpful.

Figure 5 Nature of participants’ experience with the CEFR

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

26

Figure 6 Participants’ attitudes to the CEFR and its use in understanding GCSE

standards

As part of their online familiarisation for the receptive skills, the participants were

asked about their experience of writing reading or listening comprehension tasks in

either panel target language or another language, as well as about their experience

of writing reading or listening comprehension tasks targeted at specific CEFR levels.

Figure 7 shows that the majority of participants in each panel stated that they had at

least some experience in each of these domains. Only one participant in the German

panel and one in Spanish had some experience of standard setting for language

tests.

Given that the starting point for the majority of the participants was some familiarity

and practical experience of using the CEFR, it was hoped that further familiarisation

and training would help to get everyone to a level where they can usefully contribute

to the linking study. In particular, further opportunity for discussion of the relevant

CEFR scales in relation to the standard linking method used for listening and reading

comprehension assessments, was provided at the start of each standard linking

meeting.

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

27

Figure 7 Experience of writing reading/listening comprehension test items and

standard setting

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

28

Familiarisation and training

Prior to undertaking any of the main activities in the study, the participants were

provided with familiarisation and training to ensure reasonable individual and

common understanding of the relevant aspects of the CEFR and of the GCSE

assessments. This aimed to ensure the integrity and quality of panellists’

judgements.

Separate familiarisation and training activities were created for productive skills and

receptive skills. Participants were contracted to complete familiarisation activities in

half a day for productive skills and half a day for receptive skills.

The majority of familiarisation and training activities were conducted online, using a

survey tool set up with a range of activities. Some of the activities required reading of

materials provided outside of the training tool. These had been provided in hard

copy. Some activities involved ranking or rating of performances and/or test

questions, which were accessed electronically via the links provided within the

training tool. The contents of each training tool, alongside the various documents

and CEFR scales provided to the participants, are presented in Appendix B and C.

The participants who took part in content mapping were provided with the

familiarisation and training activities before they carried out the content mapping

activities. They completed familiarisation for productive skills first, followed by

content mapping for productive skills. After this, they completed familiarisation for

receptive skills, followed by content mapping for receptive skills.

The rest of the participants were first provided with familiarisation for productive

skills, following which they carried out the rank ordering for productive skills (see

below). Given the constraints of participant availability, it was not possible to arrange

for separate face-to-face training and discussion sessions ahead of the rank ordering

exercise. However, it was hoped that the intuitive nature of the rank ordering task,

which is typically conducted individually from home, and helps to cancel out

systematic biases and severity/leniency effects in judgements, would have made up

for absence of face-to-face training (cf. Black and Bramley, 2008; Curcin and Black,

in prep; Jones, 2009).

Familiarisation for productive skills included the following key aspects:

• reading of excerpts from the CEFR document (ibid.) which briefly described

what the CEFR is, its conceptualisation of language ability, what illustrative

descriptors are and how to read them

• familiarisation with the global CEFR scale,sorting individual CEFR descriptors

from the CEFR global scale into levels

• self-assessment of participants’ own CEFR level using CEFR descriptors

• familiarisation with overall written and spoken production and interaction and

mediation CEFR scales

• consideration of examples of written and spoken performances with known

CEFR levels and deciding on key features that distinguish between

performances at different CEFR levels

• familiarisation with GCSE specifications and assessment materials, including

sketching answers to each question paper; familiarisation with processes of

marking and grading in GCSEs

Investigating standards in GCSE French, German and Spanish through the lens of

the CEFR

29

• familiarisation with rank ordering written and spoken performances, and

• exercises in ranking written and spoken performances

Initial familiarisation for receptive skills was provided about a week ahead of the

panel meetings during which the linking of assessment standards for receptive skills

was conducted. It was conducted individually, from home, using the training tool

provided. Further opportunity for discussion of the relevant CEFR scales in relation

to the method used for linking the standards, as well as in relation to use of the

CEFR in standard linking exercises, was provided at the start of each standard

linking session.

Initial familiarisation for receptive skills included the following key aspects: