Praise for

Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and

Delivery, Second Edition

“ It's often the slim books that have the most impact. Strunk and White for proper English.

Robert’s Rules of Order for running meetings. Both deceptively short, with huge impact. To

these I find it easy to add Presentation Zen for moving an audience. Embrace this wonderful

guide and gain the power of crafting simple and clear messages. Garr Reynolds provides

techniques and examples in a manner that, quite naturally, adheres to the same principles

as what he teaches.”

“ Garr is a beacon of hope for frustrated audiences everywhere. His design philosophy and

fundamental principles bring life to messages and can invigorate careers. His principles of

simplicity are as much a journey of the soul as they are restraint of the mouse.”

“ Presentation Zen changed my life and the lives of my clients. As a communications specialist,

I was searching for a way to create visuals that support the narrative without detracting from

the story. The philosophy and approach so elegantly explained in Garr's book will inspire your

audience. Don't even think of giving another presentation without it!”

“ Garr has broken new ground in the way we think about the power of presentations, and more

important, has taught an entire generation of communicators how to do a better job. Don’t

miss this one.”

“ If you care about the quality and clarity of your presentations—and you should—pick up this

book, read every page, and heed its wisdom. Presentation Zen is a contemporary classic.”

“ Four years ago, Garr’s Presentation Zen literally changed the world of communications. Almost

overnight, what was once fluffy, stale, and boring became sharp, brisk, and even (can we say

it?) fun. A million radically-improved speeches later, the world is ready for a refresher—and

just when we need it most, Garr delivers the magic again.”

—Ric Bretschneider, Senior Program Manager,

PowerPoint Development Team 1993-2010

—Nancy Duarte, CEO, Duarte, Inc., and

author of slide:ology and resonate

—Carmine Gallo, author of The Presentation

Secrets of Steve Jobs

—Seth Godin, legendary presenter

and author of We Are All Weird

—Daniel H. Pink, author of

Drive and A Whole New Mind

—Dan Roam, author of Blah-Blah-Blah

and The Back of the Napkin

This page intentionally left blank

Garr Reynolds

Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery

presentation

zen

2

nd

Edition

revised & updated

Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery

Second Edition

Garr Reynolds

New Riders

1249 Eighth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

510/524-2178

510/524-2221 (fax)

Find us on the Web at: www.newriders.com

To report errors, please send a note to [email protected]

New Riders is an imprint of Peachpit, a division of Pearson Education

Copyright © 2012 by Garr Reynolds

Senior Editor: Karyn Johnson

Copy Editor: Kelly Kordes Anton

Production Editor: Cory Borman

Proofreader: Roxanna Aliaga

Indexer: Emily Glossbrenner

Design Consultant in Japan: Mayumi Nakamoto

Book Cover and Interior Design: Garr Reynolds

Notice of Rights

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of

the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact permissions@

peachpit.com.

Notice of Liability

The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis without warranty. While every precaution

has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability

to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or

indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products

described in it.

Trademarks

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed

as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trademark

claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. All other product names and

services identified throughout this book are used in editorial fashion only and for the benefit of such

companies with no intention of infringement of the trademark. No such use, or the use of any trade

name, is intended to convey endorsement or other affiliation with this book.

ISBN-13: 978-0-321-81198-1

ISBN-10: 0-321-81198-4

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America

To Mom & Dad

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments, ix

Foreword by Guy Kawasaki, x

INTRODUCTION

Presenting in Today’s World, 5

PREPARATION

Creativity, Limitations, and Constraints, 31

Planning Analog, 45

Crafting the Story, 77

DESIGN

Simplicity: Why It Matters, 115

Presentation Design: Principles and Techniques, 131

Sample Visuals: Images & Text, 187

DELIVERY

The Art of Being Completely Present, 215

Connecting with an Audience, 231

The Need for Engagement, 253

NEXT STEP

The Journey Begins, 285

Photo Credits, 292

Index, 294

viii

ix

producer in Japan, for his great assistance.

The Design Matters Japan community

including Toru Yamada, Shigeki Yamamoto,

Tom Perry, Darren Saunders, Daniel Rodriguez,

Kjeld Duits, David Baldwin, Nathan Bryan,

Jiri Mestecky, Doug Schafer, Barry Louie, and

many, many others.

Back in the States, a big thank you to those

who contributed ideas and support, including

Debbie Thorn, CZ Robertson, David Roemer,

Gail Murphy, Ric Bretschneider, Howard

Cooperstein, Dan Roam and Carmine Gallo.

And thanks to Mark and Liz Reynolds for their

fantastic B&B at the beach.

I’d like to thank the thousands of subscribers

to the Presentation Zen blog and to all the blog

readers who have contacted me over the years

to share their stories and examples, especially

Les Posen in Australia.

Although I could not include all the slides

in this book, I want to thank all the people

who submitted sample slides, including: Jeff

Brenman, Chris Landry, Scott B. Schwertly, Jill

Cadarette, Kelli Matthews, Luis Iturriaga, Dr.

Aisyah Saad Abdul Rahim, Marty Neumeier,

Markuz Wernli Saito, Sangeeta Kumar, Allysson

Lucca, Pam Slim, Jed Schmidt, Merlin Mann,

and many others. Also, a big thank you to

Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt in Stockholm and Phil

Waknell and Pierre Morsa in Paris.

And, of course, my biggest supporter in

all this was my wife, Ai, who was always

understanding and a great source of inspiration

and ideas (and occasionally, chocolate-chip

cookies).

Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without

a lot of help and support. I’d like to thank the

following people for their contributions and

encouragement:

Nancy Duarte and Mark Duarte and all the

amazing staff at Duarte, Inc. in Silicon Valley,

including Nicole Reginelli and Paula Tesch for

their constant support.

At New Riders: Michael Nolan who asked me

to write this book originally and Karyn Johnson

who oversaw the book development this time

around and gave me the freedom to do it my

way (yeah, like the song). Kelly Kordes Anton

and Roxanna Aliaga, for bringing more clarity to

my writing and uncovering errors and offering

advice for improvement. Mimi Heft for her

help with the design and the cover. Hilal Sala,

for her great help and guidance in the first

edition, and to Cory Borman, for his talent and

guidance in production on this edition.

Guy Kawasaki, Seth Godin, David S. Rose,

Daniel Pink, Dan Heath and Rick Heath,

Rosamund Zander, Jim Quirk, and Deryn Verity

for their enlightened advice and content in the

early stages of the process.

Jumpei Matsuoka and all the cool people at

iStockphoto.com for their tremendous support

with the images and the special offer that’s

included at the back of this book.

Designer Mayumi Nakamoto for teaching

me more than I wanted to know (or thought

possible) about Adobe InDesign. June Cohen

and Michael Glass at TED for their help with

the images. Daniel Lee at Mojo for his help

with the credits. Aaron Walker, Tom Grant’s

x

Foreword by Guy Kawasaki

Because this is a book about presenting better with slides,

I thought it would be appropriate to show the foreword

as a slide presentation. As far as I know, this is the first

foreword in history presented in a book as a series of

presentation slides. Now, good slides should enhance a live

talk; slides are not meant to tell the whole story without

you there. But from the slides on the next page, I think

you can get my point. If I were to give a live talk about why

you should buy this book, the slides would look something

like this.

Guy Kawasaki

Author of Enchantment: The Art of

Changing Hearts, Minds, and Actions,

and former chief evangelist of Apple

www.guykawasaki.com

xi

77

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

4

During your time off the grid, you brainstormed alone or perhaps with a small

group of people. You stepped back to get the big picture, and you identified

your core message. You now have a clearer picture of the presentation content

and focus even if you do not have all the details worked out yet. The next step

is to give your core message and supporting messages a logical structure.

Structure will help bring order to your presentation and make it easier for you

to deliver it smoothly and for your audience to understand your message easily.

Before you go from analog to digital—taking your ideas from sketches on

paper and laying them out in PowerPoint or Keynote—it is important to keep

in mind what makes your ideas resonate with people. What makes some

presentations absolutely brilliant and others forgettable? If your goal is to

create a presentation that is memorable, then you need to consider how you

can craft messages that stick.

One of the components for creating sticking messages is story. We tell

stories all the time. Think about times you may have been camping with a

group of people, taking a tiny step back to a more primitive time, where the

evening develops into long sessions of storytelling around the campfire. There

is something very natural, compelling, and memorable about both telling and

listening to stories.

Crafting the Story

78

Presentation Zen

What Makes Messages Stick?

Most of the great books that will help you make better presentations are not

specifically about presentations at all, and they are certainly not about how to

use slideware. One such book is Made to Stick (Random House) by Chip and

Dan Heath. The Heath brothers were interested in what makes some ideas

effective and memorable and others utterly forgettable. Some stick, and others

fade away. Why? What the authors found—and explain simply and brilliantly

in their book—is that “sticky” ideas have six key principles in common:

simplicity, unexpectedness, concreteness, credibility, emotions, and stories.

And yes, these six compress nicely into the acronym SUCCESs.

The six principles are relatively easy to incorporate into messages—including

presentations and keynote addresses—but most people fail to use them. Why?

The authors say the biggest reason most people fail to craft effective or “sticky”

messages is because of what they call the “Curse of Knowledge.” The Curse

of Knowledge is essentially the condition whereby the deliverer of the message

cannot imagine what it’s like not to possess his level of background knowledge

on the topic. When he speaks in abstractions to the audience, it makes perfect

sense to him but him alone. In his mind, it seems simple and obvious. The

six principles—SUCCESs—are your weapons, then, to fight your own Curse of

Knowledge (we all have it).

Here’s an example the authors used early in their book to explain the

difference between a good, sticky message and a weak garden-variety message.

Look at these two messages, which address the same idea. One of them should

seem very familiar to you.

“Our mission is to become the international leader in the space

industry through maximum team-centered innovation and

strategically targeted aerospace initiatives.”

Or

“ …put a man on the moon and return him safely by the end of

the decade.”

79

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

The first message sounds similar to CEO-speak today and is barely

comprehensible, let alone memorable. The second message—which is actually

from a 1961 speech by John F. Kennedy—has every element of SUCCESs,

and it motivated a nation toward a specific goal that changed the world. JFK,

or at least his speechwriters, knew that abstractions are not memorable, nor

do they motivate. Yet how many speeches by CEOs and other leaders contain

phrases such as “maximize shareholder value yada, yada, yada?” Here’s a

quick summary of the six principles from Made to Stick that you should keep

in mind when crystallizing your ideas and crafting your message for speeches,

presentations, or any other form of communication.

• Simplicity. If everything is important, then nothing is important. If

everything is a priority, then nothing is a priority. You must be ruthless

in your efforts to simplify—not dumb down—your message to its

absolute core. We’re not talking about stupid sound bites here. Every

idea can be reduced to its essential meaning if you work hard enough.

For your presentation, what’s the key point? What’s the core? Why does

(or should) it matter?

• Unexpectedness. You can get people’s interest by violating their

expectations. Surprise people. Surprise will get their interest. But to

sustain their interest, you have to stimulate their curiosity. The best way

to do that is to pose questions or open holes in people’s knowledge and

then fill those holes. Make the audience aware that they have a gap in

their knowledge and then fill that gap with the answers to the puzzle (or

guide them to the answers). Take people on a journey.

• Concreteness. Use natural speech and give real examples with real

things, not abstractions. Speak of concrete images, not of vague

notions. Proverbs are good, say the Heath brothers, at reducing abstract

concepts to concrete, simple, but powerful (and memorable) language.

For example, the expression iiseki ni cho or “kill two birds with one

stone” is easier than saying something like “let’s work toward maximizing

our productivity by increasing efficiency across many departments.”

And the phrase “go to the moon and back” by JFK (and Ralph Kramden

before him)? Now that’s concrete. You can visualize that.

80

Presentation Zen

• Credibility. If you are famous in your field, you may have built-in

credibility (but even that does not go as far as it used to). Most of us,

however, do not have that kind of credibility, so we reach for numbers

and cold, hard data to support our claims as market leaders and so on.

Statistics, say the Heath brothers, are not inherently helpful. What’s

important is the context and the meaning. Put it in terms people can

visualize. “Five hours of battery life” or “Enough battery life to watch

your favorite TV shows nonstop on your iPod during your next flight

from San Francisco to New York”? There are many ways to establish

credibility—a quote from a client or the press may help, for example.

But a long-winded account of your company’s history will just bore your

audience.

• Emotions. People are emotional beings. It is not enough to take people

through a laundry list of talking points and information on your slides;

you must make them feel something. There are a million ways to help

people feel something about your content. Images are one way to

have audiences not only understand your point better but also have a

more visceral and emotional connection to your idea. Explaining the

devastation of the Katrina hurricane and floods in the United States, for

example, could be done with bullet points, data, and talking points. But

images of the aftermath and the pictures of the human suffering that

occurred tell the story in ways words, text, and data alone never could.

Just the words “Hurricane Katrina” conjure vivid images in your mind.

Humans make emotional connections with people, not abstractions.

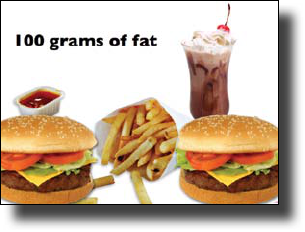

When possible, put your ideas in human

terms. “100 grams of fat” may seem concrete

to you, but for others it is an abstraction.

A picture of an enormous plate of greasy

French fries, two cheeseburgers, and a large

chocolate shake will hit people at a more

visceral level. “So that’s what 100 grams of

fat looks like!”

81

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

• Stories. We tell stories all day long. It’s how humans have always

communicated. We tell stories with our words and even with our art

and music. We express ourselves through the stories we share. We

teach, we learn, and we grow through stories. In Japan, it is a custom

for a senior worker (sempai) to mentor a younger worker (kohai ) on

various issues concerning company history and culture and how to

do the job. The sempai does much of his informal teaching through

storytelling although nobody calls it that. Once a younger worker

hears the story of what happened to the poor guy who didn’t wear his

hardhat on the factory floor, he never forgets the lesson (and he never

forgets to wear his hardhat). Stories get our attention and are easier

to remember than lists of rules. People love Hollywood, Bollywood,

and indie films. People are attracted to “story.” Why is it, though,

that when the majority of smart, talented, story-loving people have

the chance to present, they usually resort to generating streams of

vaguely connected information rather than stories or examples and

illustrations? Great ideas and presentations have an element of story

to them.

I

’ve used these slides in live talks

while reviewing the key ideas found

in Made to Stick by Chip and Dan

Heath. (All images on this page and

opposite page from iStockphoto.com.)

I believe this nation should commit

itself to achieving the goal, before this

decade is out, of landing a man on

the Moon and returning him safely to

the Earth.

— John F. Kennedy

May 25, 1961

83

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

84

Presentation Zen

Story and Storytelling

Before there was the written word, humans used stories to transfer culture

from one generation to the next. Stories are who we are, and we are our stories.

Stories may contain analogies or metaphors, powerful tools for bringing people

in and helping them understand our thoughts clearly and concretely. The best

presenters illustrate their points with stories, often personal ones. The easiest

way to explain complicated ideas is through examples or by sharing a story that

underscores the point. If you want your audience to remember your content,

then find a way to make it more relevant and memorable by strengthening your

core message with good, short, stories or examples.

Good stories have interesting, clear beginnings; provocative, engaging

content in the middle; and a clear conclusion. I am not talking about fiction

here. I am talking about reality, regardless of the topic. Remember that

documentary films, for example, “tell the story” of whatever it is they are

reporting on. Documentaries do not simply tell facts; rather, they engage us

with the story of war, scientific discovery, a dramatic sea rescue, climate

change, and so on. We are wired to forget what our brains perceive as

unimportant to our survival. Our conscious mind tells us to read the physical

chemistry book over and over because we need to pass the class, but our brain

keeps telling us this is dull, uninteresting, and unimportant to our survival.

The brain cares about story.

The Power of Story

Story is an important way to engage the audience and appeal to people’s need

for logic and structure in addition to emotion. Humans are predisposed to

remembering experiences in the narrative form; we learn best with a narrative

structure. Humans have been sharing information aurally and visually far

longer than we have been getting information by reading lists. A 2003 Harvard

Business Review article on the power of story says storytelling is the key to

leadership and communication in business: “Forget PowerPoint and statistics,

to involve people at the deepest level you need to tell stories.”

85

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

In an interview with the Harvard Business Review, legendary screenwriting

coach Robert McKee suggests a big part of a leader’s job is to motivate people

to reach certain goals. “To do that she must engage their emotions,” McKee

says, “and the key to their hearts is story.” The most common way to persuade

people, says McKee, is with conventional rhetoric and an intellectual process

that, in the business world, often consists of a typical PowerPoint presentation

in which leaders build their case with statistics and data. But people are not

moved by statistics alone, nor do they always trust your data. “Statistics are

used to tell lies...while accounting reports are often BS in a ball gown.” McKee

says rhetoric is problematic because while we are making our case others are

arguing with us in their heads using their own statistics and sources. Even

if you do persuade through argument, says McKee, this is not good enough

because “people are not inspired to act on reason alone.” The key, then, is to

aim to unite an idea with an emotion, which is best done through story. “In

a story, you not only weave a lot of information into the telling but you also

arouse your listener’s emotion and energy,” he says.

Look for the Conflict

A good story is not the beginning-to-end tale of how results meet expectations,

McKee says. This is boring. Instead, it’s better to illustrate the “struggle

between expectation and reality in all its nastiness.” What makes life

interesting is “the dark side” and the struggle to overcome the negatives—

struggling against negative powers is what forces us to live more deeply, says

McKee. Overcoming negative powers is interesting, engaging, and memorable.

Stories such as this are more convincing.

The biggest element a story has, then, is conflict. Conflict is dramatic. At

its core, story is about a conflict between our expectations and cold reality.

Story is about an imbalance and opposing forces or a problem that must

be worked out. A good storyteller describes what it’s like to deal with these

opposing forces such as the difficulty of working with scarce resources, making

difficult decisions, or undertaking a long journey of scientific discovery, and

so on. People prefer to present only the rosy (and boring) picture. “But as

a storyteller, you want to position the problems in the foreground and then

show how you’ve overcome them,” says McKee. If you tell the story of how

you struggled with antagonists, the audience is engaged with you and your

material.

86

Presentation Zen

Contrasts Are Compelling

Whether we are talking about graphic design or the components of a story,

the principle of contrast is one of the most fundamental and important

elements to include. Contrast is about differences, and we are hardwired to

notice differences. You can see the principle of contrast everywhere in good

storytelling, including filmmaking. For example, in Star Wars IV, there is

obviously compelling contrast between the good and noble Rebel Alliance

and the dark side of the Death Star and the evil empire. Yet great contrasts

exist even between main characters in the story who are on the same side.

The young, naïve, idealistic Luke Skywalker character contrasts with the old,

wise, and realistic Obi-Wan Kenobi. The level-headed, diplomatic, young

Princess Leia contrasts with the slightly cocky, irreverant, older Han Solo.

These characters are compelling to millions of fans because of their inherent

contrasts and the series of negotiations they go through as they deal with

their differences. Even R2D2 and C3PO are engaging characters, in large part

because of their strikingly different personalities. In your own presentations,

look for contrasts such as before/after, past/future, now/then, problem/solution,

strife/peace, growth/decline, pessimism/optimism, and so on. Highlighting

contrasts is a natural way to bring the audience into your story and make your

message more memorable.

Using Storytelling Principles in Presentations

You do not always have a lot of time to prepare your presentation or perhaps it

is difficult to see what the story is, so here are three simple steps you can use

to prepare virtually any presentation relatively quickly.

Basic elements to include in your story:

1. Identify the problem. (This could be a problem, for example, that your

product solves.)

2. Identify causes of the problem. (Give actual examples of the conflict

surrounding the problem.)

3. Show how and why you solved the problem. (This is where you provide

resolution to the conflict.)

87

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

Essentially, that’s it: Introduce the problem you have (or did have) and how

you will solve it (or did solve it). Give examples that are meaningful and

relevant to your audience. Remember, story is sequential: “This happened,

and then this happened, and therefore this happened, and so on.” Take

people on a journey that introduces conflict and then resolves that conflict. If

you can do this, you will be miles ahead of most presenters who simply recall

talking points and broadcast lists of information. Audiences tend to forget

lists and bullet points, but stories come naturally to us; it’s how we’ve always

attempted to understand and remember the bits and pieces of experience.

Robert McKee’s point is that you should not fight your natural inclination to

frame experiences into a story; instead, embrace this and tell the story of your

experience of the topic to your audience.

Stories and Emotions

Our brains tend to recall experiences or stories that have a strong emotional

element to them. The emotional components of stories are what helps

them be remembered. Earlier this year, four students in my Japanese labor

management class did a presentation on employment security in Japan. Three

days later, when I asked other students to recall the most salient points of

the presentation, what they remembered most vividly were not the labor laws,

the principles, and the changes in the labor market in Japan but, rather, the

topic of karoshi, or suicide related to work, and the issue of suicides in Japan,

topics that were quite minor points in the hour-long presentation. Perhaps five

minutes out of the hour were spent on the issue of karoshi, but that’s what the

audience remembered most. It’s easy to understand why. The issue of death

from overworking and the relatively high number of suicides are extremely

emotional topics that are not often discussed. The presenters cited actual

cases and told stories of people who died as a result of karoshi. The stories

and the connections they made with the audience caused these relatively

small points to be remembered because emotions such as surprise, sympathy,

and empathy were all triggered.

Kamishibai: Lessons in Visual

Storytelling from Japan

Kamishibai is a form of visual and participatory

storytelling that combines the use of hand-drawn

visuals with the engaging narration of a live presenter.

Kami

(紙)

means “paper” and shibai

(芝居)

means

“play/drama.” The origins of kamishibai can be traced

back to various picture storytelling traditions in

Japan, which include etoki and emaki scrolls and other

forms of visual storytelling dating back centuries.

However, the form of kamishibai that one thinks of

today developed around 1929 and was popular in the

1930s, and ’40s, all but dying out with the introduction

of television later in the 1950s. Typical kamishibai consisted of a presenter who stood

to the right of a small wooden box or stage that held the 12–20 cards featuring

the visuals that accompanied each story. This miniature stage was attached to the

storyteller’s bicycle, from which he sold candy to the small children who gathered

before the show (this was originally how the storyteller could make a little money).

The presenter changed the cards by hand, varying the speed of the transition to match

the flow of the story he was telling. The best kamishibai presenters did not read the

story, but instead kept their eyes on the audience and occasionally on the current card

in the frame.

Kamishibai is as different from picture books as modern presentation visuals are

different from documents. In the case of a picture book, there can be more visual

details and text. However, picture books are usually read alone unlike kamishibai which

is designed to be presented in front of a larger group gathered around the presenter

and his visuals.

Although kamishibai is a form of visual storytelling that became popular more than

eighty years ago, the lessons from this craft can be applied to modern multimedia

presentations. Tara McGowan, who wrote The Kamishibai Classroom (Libraries

Unlimited), says that kamishibai visuals are more like the frames in a movie. “Kamishibai

pictures are designed to be seen only for a few [moments], so extraneous details

detract from the story and open up the possibilities of misinterpretation.” It's

important to design each card, she says, “...to focus the audience’s attention on

characters and scenery that are most important at any given moment. If clarity

and economy of expression are the goals, it would be hard to find a more perfect

medium.” It’s easy to imagine how we can apply the same spirit of kamishibai to our

modern-day presentations that include the use of multimedia and a screen. Here are

five tips from kamishibai that we can apply to our presentations today:

1. Visuals should be big, bold, clear, and easy to see.

2. Allow graphic elements to fill the frame and bleed off the edges.

3. Use visuals in an active way, not a decorative one.

4. Aim to carefully trim back the details.

5. Make your presentation—visuals and narration—participatory.

Photo on this page: Aki Sato, Creative Commons

Photo on opposite page:

©

Horace Bristol/CORBIS

90

Presentation Zen

Stories and Authenticity

I have seen pretty good (though not great) presentations with average delivery

and graphics that were relatively effective because the speaker told relevant

stories in a clear, concise manner to support his points in a voice that was

human, not formal. Rambling streams of consciousness will not get it done;

audiences need to hear (and see) your points illustrated in real language.

Earlier this year, in fact, I saw a fantastic presentation by the CEO of one

of the most famous foreign companies in Japan. The CEO’s PowerPoint slides

were of mediocre design, and he made the mistake of having not one but

two assistants off to the side to advance his slides to match his talk. The

assistants seemed to have difficulty with the slideware, and often the wrong

slide appeared behind the presenter, but this powerful man simply shrugged

his shoulders and said “…ah, doesn’t matter. My point is…” He moved

forward and captivated the audience with his stories of the firm’s past failures

and recent successes, stories that contained more captivating and memorable

practical business lessons than most business students will get in an entire

semester or more.

It is true that the presentation would have been even better if the slides had

been better designed and used properly, but in this particular case, the CEO

gave a powerful and memorable presentation in spite of those shortcomings.

Trust me, this is very rare in the world of CEO presentations. There are four

essential reasons for his success that night: (1) He knew his material inside

and out, and he knew what he wanted to say. (2) He stood front and center and

spoke in a real, down-to-earth language that was conversational yet passionate.

(3) He did not let technical glitches get in his way. When they occurred, he

moved forward without missing a beat, never losing his engagement with the

audience. (4) He used real, sometimes humorous, anecdotes to illustrate his

points, and all his stories were supremely poignant and relevant, supporting

his core message.

91

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

What made this CEO’s presentation so compelling and memorable was that

it was, above all, authentic. His stories were from his heart and from his gut,

not from a memorized script. We do not tell a story from memory alone; we do

not need to memorize a story that has meaning to us. If it is real, then it is in

us. Based on our research, knowledge, and experience, we can tell it from our

gut. Internalize your story, but do not memorize it line by line. You can’t fake

it. You believe in your story, or you do not. And if you do not, no amount of

hyped-up, superficial enthusiasm or conviction will ever make your time with

an audience meaningful. If you do not believe it, do not know it to be true,

how can you connect and convince others with your words in story form? Your

words will be hollow.

92

Presentation Zen

It’s Not Just About Information

People who possess loads of information in a particular field have historically

been in hot demand and able to charge high fees for access to their stuffed,

fact-filled brains. This was so because facts used to be difficult to access. Not

anymore. In an era when information about seemingly anything is only a mouse

click away, just possessing information is hardly the differentiator it used to

be. What is more important today than ever before is the ability to synthesize

the facts and give them context and perspective. Picasso once said, “Computers

are useless for they can only give answers.” Computers and Google can indeed

give us routine information and facts we need. What we want from people

who stand before us and give a talk is that which data and information alone

cannot: meaning.

Remember we are living in a time when fundamental human talents are in

great demand. Anyone—indeed any machine—can read a list of features or

give a stream of facts to an audience. That’s not what we need or want. What

we yearn for is to listen to an intelligent and evocative—perhaps, at times,

even provocative—human being who teaches, inspires, or stimulates us with

knowledge and meaning, context, and emotion in a way that is memorable.

And this is where story comes in. Information plus emotion and visualization

wrapped in unforgettable anecdotes are the stuff that stories are made of.

If presentations were only about following a linear, step-by-step formula for

distributing information and facts, then no one would be complaining about

boring presentations today; after all, the majority of presentations still follow

just such a formula. And if designing visuals for your presentation were simply

a matter of following a list of rules, then why on earth should we keep wasting

our time creating slides and other multimedia? Why not simply outsource our

facts, outlines, and bullet points to someone who could do it more cheaply?

But presentations are not just about following a formula for transferring facts

in your head to the heads of those sitting before you by reciting a list of points

on a screen. (If it were, why not send an e-mail and cancel the presentation?)

What people want is something fundamentally more human. They want to hear

the story of your facts.

93

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

Finding Your Voice

The voice of the storyteller is also important. We pay attention to well-spoken

narratives that sound human, that are spoken in a conversational voice.

Why do we pay more attention to conversational speech from a storyteller

or presenter? It may be because our brain—not our conscious mind—does

not know the difference between listening to (or reading) a conversational

narrative and actually being in a conversation with a person. When you are in a

conversation with someone, you are naturally more engaged because you have

an obligation to participate. Formal speech and writing devoid of any emotion

is extremely difficult to stay with for more than a few minutes. Your conscious

mind has to remind you to “stay awake, this is important!” But someone who

speaks in a natural, conversational style is far easier to stay engaged with.

Majora Carter speaks with a “human voice” at

the TED Conference in 2005, explaining her fight

for environmental justice in the South Bronx.

(Photo: TED/ leslieimage.com)

94

Presentation Zen

Dana Atchley (1941–2000)

A Digital Storytelling Pioneer

Dana Atchley was a legend and pioneer in the field of digital storytelling. His clients

included Coke, EDS, Adobe, Silicon Graphics, and many others. He even worked

with Apple as a charter member of the AppleMasters program. In the ’90s. Atchley

was helping senior executives create emotional, compelling talks that used the

latest technology to create “digital stories” that connected with and appealed to

audiences in a more visceral, visual, emotional, and memorable way. If Atchley had

not passed away at age 59 in 2000, presentations—even in the world of business—

might be far more appropriate, engaging, and effective today. Here’s what Dana

Atchley said about digital storytelling:

“Digital storytelling combines the best of two worlds: the ‘new world’ of digitized

video, photography, and art, and the ‘old world’ of telling stories. This means the ‘old

world’ of PowerPoint slides filled with bullet point statements will be replaced by a

‘new world’ of examples via stories, accompanied by evocative images and sounds.”

Here’s what Dan Pink, writing for Fast Company, said about Dana Atchley and his

mission in this excerpt from a 1999 article titled “What’s Your Story?”

“[W]hy does communication about business remain so tedious? Most businesspeople

describe their dreams and strategies—their stories—just as they’ve been doing

it for decades: stiffly, from behind a podium, and maybe with a few slides. Call

it ‘Corporate Sominex.’ Digital storytelling is more than a technique. In fact, it’s

become something of a movement among both artists and businesspeople.”

This bit from the Fast Company article makes the future of business presentations

sound so promising. I get excited reading this and thinking about the possibilities.

Yet, since 1999, how much has really changed? Some people today are indeed using

digital technology in presentations the way Atchley envisioned. But there is such a

long, long way to go before we rid the business world of the “corporate Sominex”

phenomenon.

Learn more about Dana Winslow Atchley III and his brilliant contributions on the

Next Exit website: www.nextexit.com.

95

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

The Process

The problem with slideware applications—PowerPoint, in particular, because

it’s been around longer and influenced a generation—is that they have, by

default, guided users toward presenting in outline form with subject titles and

bullet points grouped under each topic heading. This is similar to the good ol’

topic sentence in a high school composition class. It seems logical enough,

but it is a structure that makes the delivery of the content utterly forgettable

for the audience. Storyboarding can help. If you take the time in this part of

the preparation stage to set up your ideas in a logical fashion in storyboard

format, you can then visualize the sequential movement of your content

narrative and the overall flow and feel of the presentation.

Because you have already identified your core message away from the

computer, you can now begin to create a storyboard that will give shape to the

story of your short presentation. Storyboards have their origins in the movie

industry but are used often in business, particularly in the field of marketing

and advertising.

One of the simplest and most useful features of PowerPoint and Keynote is

the Slide Sorter view (Light Table view in Keynote). You can take your notes

and sketches and create a storyboard directly in PowerPoint or Keynote, or you

can remain “analog” a bit longer and draft a storyboard on paper or by using

Post-its or a whiteboard, etc.

Each situation and each individual is different, and there are indeed many

paths to better presentations, including better preparation. My personal

approach moving from rough analog sketches to digital slides is not uncommon

at all. I have been surprised, however, that for the most part, individual

professionals, entrepreneurs, and students usually just open up slideware, type

about a dozen subject slides, and then fill them with talking points. This is not

an effective approach, nor is it a method I recommend although it is common.

Below is the five-step approach I usually take. I sometimes skip the

third and fourth steps, but I find it works well when a group is planning the

presentation. For students working on a group presentation, step 3 is vital.

96

Presentation Zen

Step 1

Brainstorming. Step back, go analog, get away from

the computer, tap into the right brain, and brainstorm

ideas. You need not show restraint here. Editing comes

later. In brainstorming, quantity matters. Here, I put

ideas down on cards or sticky notes and place them on

a table or whiteboard. This is something you can do by

yourself or in a group. When working in a group, do not

judge others’ ideas. Simply write them down and place

them with the others for the time being. At this stage,

even crazy ideas are OK because the offbeat ideas may

lead to more practical yet still compelling supporting

ideas later on. As the great Linus Pauling once said, “The

best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas.”

Step 2

Grouping and identifying the core. In this step, I look to

identify one key idea that is central (and memorable)

from the point of view of the audience. What is the

“it” that I want them to get? I use “chunking” to group

similar ideas while looking for a unifying theme. The

presentation may be organized into three parts, so first

I look for the central theme that will be the thread

running through the presentation. There is no rule

that says your presentation should have three sections

or three “acts.” However, three is a good number to

aim for because it is a manageable constraint and

generally provides a memorable structure. Regardless

of how many sections I use, there is only one theme.

It all comes back to supporting that key message. The

supporting structure—the three parts—

is there to back

up the core message and the story.

Participants in a Presentation Zen seminar

at the Kyoto Institute of Technology in Japan

begin to group and identify core messages

after their brainstorming session.

Brainstorming

“

off the grid

”

away from the computer.

This is very much a nonlinear process, and the more

ideas the better. Here ideas are suggested and quickly

jotted down on Post-it notes.

97

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

Step 3

Storyboarding off the computer. I take the Post-it notes roughly arranged in step

2 and lay them out in a sequence. The advantage of this method (compared

to the Slide Sorter view in PowerPoint or the Light Table view in Keynote) is

that I can easily add content by writing on an additional Post-it and sticking

it under the appropriate section without ever losing sight of the structure

and flow. In software, I have to switch to Slide mode to type or add an image

directly on a slide and then go back to the Slide Sorter mode to see the big-

picture structure. Alternatively—and this is very popular with my Japanese

business students—you can print out blank slides, 12 slides per sheet, which

essentially gives you a larger version of a Moleskine Storyboard. If you want

larger slides, you can print out nine slides or six. You then can tape these to

the wall or spread them out on the desk, keeping them in a notebook when

you’re done. As shown below, you can sketch your visuals and write down your

key points in a printed version of slideware notes.

After eliminating many ideas created in their

brainstorming session, these participants in

Japan begin to build the structure of their

presentation by arranging their messages

in sequence. This part is still a bit messy as

they are continuing to eliminate and add new

ideas to improve their overall story.

98

Presentation Zen

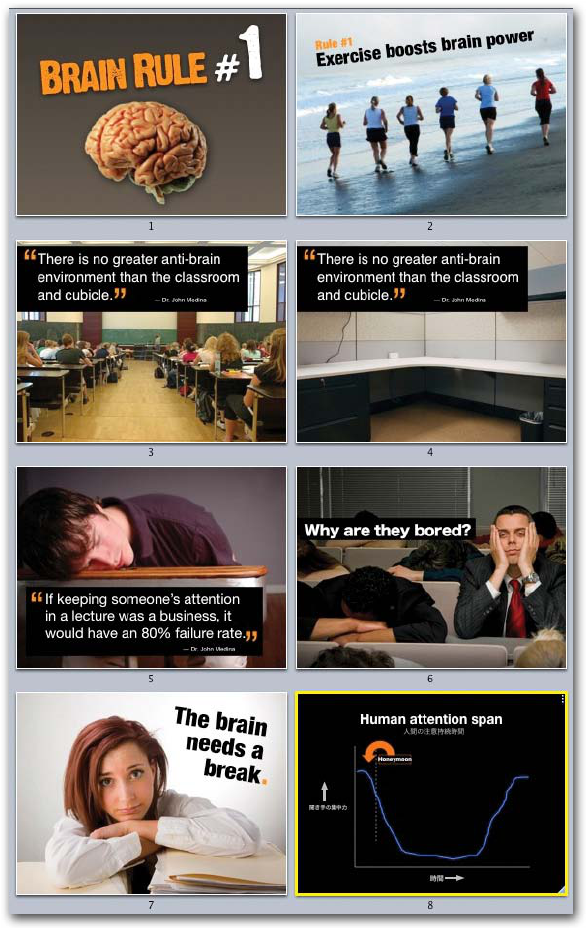

A sample of just eight slides from a

section of a presentation on audience

engagement, citing some of the ideas

from the book Brain Rules by John

Medina. I am not going to win an art

competition for my quick sketches,

but that does not matter. These rough

sketches are just for me. (Image shown

here is of the Presentation Zen

Storyboarding Sketchbook (New

Riders).Later, I used them to assemble

simple visuals on the computer (opposite

Step 4

Sketch your visuals. Now that you have identified a clear theme, a core

takeaway message, and two or three sections containing an appropriate

amount of detail (including data, stories, quotes, facts, and so on), you

can begin to think about visuals. How can you visualize your ideas to make

them more memorable and accessible to your audience? Using a sketchbook

and sticky notes, or even scratch paper, begin to change the words on your

paper or sticky notes into rough sketches of images—images that eventually

will become high-quality photography, quantitative displays, charts, slides

featuring quotations, etc. You can use some of the same sticky notes to sketch

the rough visualizations you used in step 3, and you can replace some of those

notes with new sticky notes.

99

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

100

Presentation Zen

Step 5

Storyboarding on the computer. If you have a clear sense of your structure, you

can skip steps 3 and 4 and start building the flow of your presentation directly

in slideware (though I recommend going through those storyboarding and

sketching steps if the stakes of the presentation are high). Create a blank slide

using a template of your choosing (or the simplest version of your company’s

template if you must use it). I usually choose a blank slide and then place a

simple text box inside it with the size and font I’ll use most often. (You can

create multiple master slides in PowerPoint and Keynote.) Then I duplicate

several of these slides because they will contain the visual content of my

presentation: short sentences or single words, images, quotes, charts and

graphs, etc. The section slides—what presentation guru Jerry Weismann calls

bumper slides—should be a different color with enough contrast that they

stand out when you see them in the Slide Sorter view. You can have these

You can also use your ideas generated in step 3 to

create rough sketches in printed blank slides from your

slideware. In this example, key points of the narration

behind each visual are written on the side. These

sketches became the slides on the right.

Shown here are the title slide,

the “hook,” and the roadmap of

the talk. The actual “hook” and

background section of the obesity

problem covered several slides

before I introduced the roadmap/

outline. (Images used in these

slides from iStockphoto.com.)

101

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

ABOVE Rough outline from step 2 for a

presentation I created on presentation delivery called

“The Naked Presenter.” Here, I used a simple pad

instead of Post-it notes. However, from the ideas on

this pad, I sketched rough visuals and put down key

words on Post-it notes to build the structure just as in

step 4 (not shown here).

RIGHT The start of the storyboarding process

in step 5 for the same presentation. Although the

sketches from step 4 are not shown here, from the

outline structure from step 2, you can see the simple

structure before slides were added to the appropriate

sections. The total number of slides ended up being

more than 200.

slides hidden, so you see them only when planning in Slide Sorter view if you

prefer; however, in my case, these slides will serve to give visual closure to one

section and open the next section.

Now that I have a simple structure in the Slide Sorter view, I can add visuals

that support my narrative. I have an introduction in which I introduce the

issue or “the pain” and introduce the core message. I then use the next three

sections to support my assertions or “solve the pain” in a way that is interesting

and informative but that never loses sight of the simple core message.

Nancy Duarte

CEO of Duarte, Inc., the world’s leading presentation and story firm.

Clients include the greatest brands and thought leaders in the world.

Nancy Duarte talks about storyboards and the process

of presentation design.

Much of our communication today exhibits the

quality of intangibility. Services, software, causes,

thought leadership, change management, company

vision—they’re often more conceptual than

concrete, more ephemeral than firm. And there’s

nothing wrong with that. But we regularly struggle

when communicating these types of ideas because

they are essentially invisible. It’s difficult to share

one’s vision when there’s nothing to see. Expressing

these invisible ideas visually, so they feel tangible

and actionable, is a bit of an art form, and the best

place to start is not with the computer. A pencil

and a sheet of paper will do nicely.

Why take this seemingly Luddite approach?

Because presentation software was never

intended to be a brainstorming or drawing tool.

The applications are simply containers for ideas

and assets, not the means to generate them. Too

many of us have fallen into the trap of launching

our presentation application to prepare our

content. In reality, the best creative process

requires stepping away from technology and

relying on the same tools of expression we grew

up with—pens and pencils. Quickly sketch lots of

ideas. These can be words, diagrams, or scenes;

they can be literal or metaphorical. The only

requirement is that they express your underlying

thoughts. The best thing about this process is that

you don’t need to figure out how to use drawing

tools or where to save the file. Everything you

need you already have (and don’t say you can’t

draw; you’re just out of practice). This means

you can generate a large quantity of ideas in a

relatively short amount of time.

For me, one idea per sticky note is preferable.

And I use a Sharpie. The reason? If it takes more

space than a Post-it and requires more detail than

a Sharpie can provide, the idea is too complex.

Simplicity is the essence of clear communication.

Additionally, sticky notes make it easy to arrange

and rearrange content until the structure and

flow feels right. On the other hand, many people

on my team use a more traditional storyboarding

approach, preferring to linearly articulate detailed

ideas. That’s fine, too. The point is not to prescribe

exactly how to work but to encourage you to

generate a lot of ideas.

Often ideas come immediately. That’s good, but

avoid the potential pitfall of going with the first

thing that comes to mind. Continue to sketch and

force yourself to think through several more ideas.

It takes discipline and tenacity—especially when

it feels like you solved it on the first try. Explore

words and word associations to generate several

ideas. Use mind-mapping and word-storming

techniques to create yet more ideas (digital natives

might prefer mind-mapping software for this phase).

Stronger solutions frequently appear after four or

five ideas have percolated to the top. Continue

generating ideas even if they seem to wander

down unrelated paths; you never know what you

might find, after all. Then, once you’ve generated

www.duarte.com

an enormous amount of ideas, identify a handful

that meet the objective of the vision or concept

you’re trying to communicate. It matters less what

form they take at this point than that they get your

message across.

By the way, cheesy metaphors are a cop-out. If

you feel tempted to use a picture of two hands

shaking in front of a globe, put the pencil down,

step away from the desk, and think about taking

a vacation or investigating aromatherapy. Push

yourself to generate out-of-the-box ideas. Take

the time and spend the creative energy because

the payoff will be a presentation people not only

remember, but one they take action on.

Now, begin to sketch pictures from the ideas.

These sketches become visual triggers that spark

more ideas. The sketching process should be loose

and quick—doodles really. Generate as many

pictures as you can. In this way, sketching serves

as proof-of-concept because ideas that are too

complex, time consuming, or costly will present

themselves as ripe for elimination. Don’t worry

about throwing things away—that’s why you

generated a lot of ideas in the first place. In fact,

you’re ultimately going to have to throw all of them

away except for one (designers recognize this as

the destructive aspect of the creative process; it’s

a good thing). Some of the ideas you generate may

require multiple scenes built across a few slides

versus a snapshot on a single slide. On the other

hand, sometimes it’s as simple as using the perfect

picture or diagram. Focus on whatever works best,

not on the idea that’s easiest to execute.

Be prepared to enlist the help of a designer. (You

did plan far enough ahead to make sure you’ve got

one available, right?) There’s no shame in seeking

professional help; what’s important is effective

communication, regardless of whether or not you

have the skill set to execute it.

Brainstorming with Nancy Duarte (bottom right) and two of her

staff, Ryan and Michaela, at Duarte headquarters in Silicon Valley.

Moxie Software

www.moxiesoftware.com

Many times the best concept doesn’t exist

as a ready-to-go stock photo. Some ideas

are so unique, you have to create them from

scratch—creating a memorable visual.

Duarte, Inc. created multiple concepts for

Moxie Software. The client picked Concept 2

shown on the opposite page. All of Duarte's

planning and ideating was done by hand so

that they would not be restricted by cliché

concepts.

Design: Duarte, Inc.

Concept 1 The Illustrations and

scenes were made out of yarn. Each

slide connects to the next which gives

an illusion of panning through a scene

when transitioning to the next frame.

Concept 2 This concept

required photography to be taken

in-house at Duarte, Inc. and

many of the images were custom-

designed to create the desk and

office scenes as an environment.

If you feel tempted to use a picture

of two hands shaking in front of a

globe, put the pencil down, step

away from the desk, and think about

taking a vacation or investigating

aromatherapy.

—Nancy Duarte

107

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

Editing and Restraint

I am a bit of a Star Wars geek. Over the years, as I’ve learned more about

the incredible creativity (and hard work) behind Lucas’s films, I realized

we mere mortals can learn much about presentations (which are essentially

opportunities to tell our story) by listening to the advice of master storytellers

such as George Lucas.

As I researched the numerous interviews over the years of Lucas talking

about the making of the Star Wars films, one key idea often discussed was the

importance of editing like mad to get the story down to about two hours. To do

this, they scrutinized every scene to make sure that it actually contributed to

the story—no matter how cool it was. If, during the editing process, a scene

was judged to be superfluous to the story in any way, it was cut (or trimmed if

the length was the only problem). They were very keen on keeping to the two-

hour format because this was in the best interest of the audience.

We have all seen scenes from movies that left us scratching our heads

wondering how they contributed to the story. Perhaps the director felt the

scene was so technically cool or difficult to make that he just couldn’t stand

the thought of not including it in the film. But that would be a poor reason to

include a scene. As far as presentations go, we have all seen people include

data, facts, graphics, or a seemingly unrelated anecdote that just did not

contribute to the speaker’s overall point (which we were probably at a loss to

find anyway). Presenters often include superfluous items because they are

proud of their work and want to show it off even when it does not help support

the speaker’s particular point.

Moral of the story: Always keep the audience in mind by first keeping your

talk as short as you can and still doing an effective job telling your story.

Second, after you have prepared your presentation, go back and edit like

crazy, eliminating parts that are not absolutely crucial to your overall point or

purpose. You must be ruthless. When in doubt, cut it out.

It’s paramount that we be ruthless editors of our own material. We have to

make tough choices, choosing even not to do something (because it is not

meeting your standards, for example). The hardest thing can be deciding to

cut and even abandon material altogether, but it must be done.

108

Presentation Zen

Many people are not good at editing their presentations because they are

afraid. They figure nobody ever got fired for including too much information.

Better safe than sorry, they say. But this leads to lots of material and wasted

time. Covering your butt by including everything under the sun is not the right

place to be coming from; it’s not the most appropriate motivation. It is, after

all, only a presentation, and no matter how much you include, someone will

say, “Hey, why didn’t you say _____!” Difficult people are out there, but don’t

play to them, and do not let fear guide your decisions.

Designing a tight presentation that has the facts right but does so by giving

simple, concrete anecdotes that touch people’s emotions is not easy work, but

it’s worth it. Every successful presentation has elements of story to it. Your job

is to identify the elements of your content that can be organized in a way that

tells a memorable story.

109

Chapter 4 Crafting the Story

In Sum

•Makeyourideasstickybykeepingthingssimple,usingexamplesand

stories, looking for the unexpected, and tapping into people’s emotions.

•Apresentationisneverjust about the facts.

•Brainstormyourtopicawayfromthecomputer,chunk(group)themost

important bits. Identify the underlying theme, and be true to that theme (core

message) throughout the creation of the presentation.

•Makeastoryboardofyourideasonpaper—andthenusesoftwaretolayout

a solid structure that you can see.

•Showrestraintatalltimes,andbringeverythingbacktothecoremessage.

294

Presentation Zen

Index

1-7-7 Rule, 142

3D effects, 140

A-B

agenda slides, 239

alignment principle, 177, 185

amplification, 125–127

Anderson, Chris, 12

Articulate Executive, The, 236

Art of Possibility, The, 225

asymmetrical designs, 166–168

Atchley, Dana, 94

Atkinson, Cliff, 69

attentiveness, 248

audience

apologizing to, 238–239

connecting with, 231–239, 242,

253–263, 276

dealing with hostile, 224

getting close to, 272–273

keeping attention of, 238, 248–249,

276

projecting yourself to, 240–244

Austin, Dennis, 10

Authentic Happiness, 256

authenticity, 90–91

balance, 166–168

beginner’s mind, 33–34

bento, 5, 6

big-picture thinking, 35, 45

bilingual visuals, 158–159

B key, 275

Brain Rules, 254

brainstorming, 48, 50, 52, 96

branding, 141, 192

Breeze, James, 163

Brenman, Jeff, 194

Buchholz, Dr. Ester, 57

Budo Secrets, 223

bullet points, 5, 95, 142–143

bumper slides, 100

Burns, Ken, 22

business documents, 22

busyness, 55–56

C-D

challenging assumptions, 237

child’s mind, 33–34

clutter, 9, 117, 141

cognitive load theory, 10

comics, 22, 125–127

communication

removing barriers to, 264–265

skills for effective, 22, 25

as transfer of emotion, 20

computer, as “bicycle for mind,” 46–47

computer-generated presentations, 10

Conceptual Age, 14–19

concreteness, 79, 102

conflict, 85

connection, techniques for making,

232–239

constraints, working with, 39–42

contrast, 86, 173–174, 185

contribution, 225–226

conversational voice, 93, 242

core message, 64–66, 74, 96

creativity, 31–37, 55–56, 287

credibility, 80

Crowley, James, 120

Crowley, Sandra, 120

curiosity, stimulating, 258–259

Curse of Knowledge, 78

Dakara nani, 66

Decker, Bert, 244

delivery techniques, 9, 223–224

design. See also presentation design

importance of, 132, 185

principles, 133-185

symmetrical vs. asymmetrical,

166–168

vs. decoration, 16

Design Book, The Non-Designer’s, 133,

177

digital storytelling, 94

documentaries, 22, 25, 84

documents vs. slides, 70–71

Dreams Time, 152

dress codes, 240, 251

Drucker, Peter, 74

Duarte, Nancy, 102–103

Dytham, Mark, 41

E-F

Eenfeldt, Andreas, 202

Einstein, Albert, 116, 258

ekiben, 5

elegance, 120

elevator test, 66

emotions, 20, 80, 87, 236, 254–256

empathy, 17, 64

empty space, 161–171, 185

engagement, audience, 253–263

entertainers, 249

enthusiasm, 37, 268

Everystockphoto.com, 152

eye contact, 242

faces, 163–165

face-to-face communication, 12

films, 22, 84, 107

Fisch, Karl, 194

Flickr Creative Commons Pool, 152

font size, 244

Fotolia, 152

G-H

Gaskins, Robert, 10

Gates, Bill, 117–118

Gerard, Alexis, 144

Getty Images, 152

Godin, Seth, 10, 20–21

Going Visual, 144

golden mean/ratio, 169

Goldstein, Bob, 144

Google Docs, 11

Grant, Tom, 231–232

graphic design, 86, 120, 131, 161, 173,

288

grids, 169–171

Grimes, Tom, 141

haiku, 42

handouts, 9, 21, 68–69

hara hachi bu, 248–249, 251

Heath, Chip, 78

Heath, Dan, 78

high-touch talents, 14, 19

humor, 237, 268

I-J

Ichiun, Odagiri, 9

If You Want to Write, 35, 219

image libraries, 51, 152

imagery, storytelling through, 22

Isaacson, Walter, 117, 267

iStockphoto.com, 51, 152, 208, 292

Japanese Streets, 152

Japanese tea ceremony, 115, 121

jazz, 232–235

Jobs, Steve, 46, 117–118, 217–219, 239,

267–271

judo, 223–224

295

Index

K-L

Kaku, Michio, 258

kamishibai, 88

Kamishibai Classroom, 88

Kano, Jigoro, 223, 224

kanso, 119. See also simplicity

Kawamura, Sachiko, 39

Kawana, Dr. Koichi, 119

Kawasaki, Guy, ix, x, 168, 244

Kennedy, John F., 79

Keynote, 11, 95, 97

Klein, Astrid, 41

Kumar, Sangeeta, 200

Landry, Chris, 196

languages, combining, 158–159

laughter, 237

Laws of Simplicity, The, 39

lecterns, 241, 264–265, 272–273, 279

left-brain thinking, 14, 20, 31

length, presentation, 248–249, 270

lighting, 276–277

Light Table view, 95, 97

limitations, working with, 39–42

live talks, 25

logos, 141

Loori, John Daido, 140

Lucas, George, 107

M-O

Made to Stick, 78

Maeda, John, 39

Mann, Merlin, 208

McCloud, Scott, 125, 127

McGowan, Tara, 88

McKee, Robert, 85

McLeod, Scott, 194

meaning aptitude, 19

Medina, Dr. John, 254

meditation, 215

Meerheimb, Jasper von, 39

memory, 254

Memory and Imagination, 46

message

making it stick, 78–81

presenting core, 64–66, 74

microphones, 242–243

mindfulness, 215–216

mirror neurons, 254–256

Mogi, Kenichiro, 259

moment, being in, 219, 225–228

Morgue File, 152

Moxie Software, 104–105

multimedia presentations, 9, 10, 13, 246,

267

Naked Presenter, The, 236

NASA Image Exchange, 152

naturalness, 7, 11, 25, 119, 217

negative space, 161

noise, 134, 138

Non-Designer’s Design Book, The, 133, 177

notes, presentation, 69

novelty, 237

numbers, 268. See also statistics

Okazaki, H. Seichiro, 223

“one-corner” style, 125

online video, power of, 12

P

passion, 226–227

Pecha Kucha method, 41, 286

pen and paper, 48, 50

Perera, Gihan, 262

performance, art of, 225, 231–232

personal stories, 236

Peters, Tom, 14, 153, 236

photo credits, 292–293

Picasso, Pablo, 31, 92

picture superiority effect, 144–159

Pink, Daniel, 14, 225

planning presentations, 45–75, 95–101

playfulness, 18

podiums, 264, 279. See also lecterns

Post-it notes, 52, 95, 97, 102

Powell, Richard, 42

PowerPoint

cognitive style to, 46

creating storyboards in, 95

creators of, 10

as document-creation tool, 5, 22, 71

misuse of, 10, 11, 46, 71, 95

unconventional approach to, 41

presentation, art of, 7, 9

presentation design, 131–185, 286, 288

presentation generation, 12

presentation handouts. See handouts

presentations

characteristics of effective, 11, 12, 25,

43

in “Conceptual Age,” 14–23

crafting story for, 77

creativity in, 31–37

deciding on message for, 64–66

delivering, 223–224

editing, 107–108

length considerations, 248–249

Pecha Kucha method for, 41

planning (See planning presentations)

reading, 244–245

rules for improving, 20–21

showing structure of, 239

text vs. visuals in, 20

three components of, 69

using lectern for, 264–265

varying pace of, 270

presentation software, 11, 46. See also

PowerPoint

presentation techniques, 11

presentation technology, 11, 260

Presentation Zen

as approach, not method, 8, 25

and beginner’s mind, 33–35

letting go of the past, 23

principles of, 7, 25

Web site, 286

presenter(s)

how to become better, 286–288

and judo, 223–224

as performers, 225, 231–232

Steve Jobs as, 217–219, 266–271

for TED conference, 246–247

traits of good, 215–216, 225, 231–232,

267–271

for webinars, 262–263

Prezi, 11

professional designers, 48

projecting yourself, 240–245

proximity principle, 177, 185

PUNCH, 236–238

Q-R

quotations, 153–157

Really Bad PowerPoint, 10

remote control devices, 274

repetition, 175–176, 185

restraint, 7, 9, 11, 25, 107, 119

restrictions, working with, 39–42

Reynolds, Garr, contact information, 297

right-brain thinking, 14, 19, 20, 31, 35, 287

Rose, David S., 68

Rosling, Hans, 247, 259

royalty-free images, 152

rule of thirds, 169

296

Presentation Zen

S

Saad, Dr. Aisyah, 198

Seligman, Martin, 256

shibumi, 120

Shimizu, Eiji Han, 260

shizen, 119. See also naturalness

Shutter Stock, 152

signal-to noise ratio, 134–141, 185

simplicity, 115–129

amplification through, 125–127

and clear communications, 102

and comics, 125–127

and Presentation Zen, 7, 9, 11, 25

and sticky messages, 78, 79

and time considerations, 128

why it matters, 115–116

and Zen aesthetic, 119

sketches, 48, 50, 97, 98, 103

slide presentations. See also

presentations

creating good, 209

distributing printed version of, 68

number of slides for, 62

Presentation Zen approach to, 7–9

reading, 244–245

sample, 187–208

tools for creating, 11

vs. written documents, 70–71

for webinars, 262–263

when to use, 267

Slide Sorter view, 95, 97, 101

slideuments, 70–72

Slim, Pam, 205

software tools, 9, 11

solitude, 57

speaking ability, 12, 215–216

speeches, reading, 244–245

statistics, 85, 247

Stevens, John, 223

“sticky” messages, 78–81

story, 77–109

and authenticity, 90–91

in “Conceptual Age,” 16

conflict in, 85

contrasts in, 86

elements to include in, 86–87

finding voice for, 93

making message stick with, 81

power of, 16, 77, 84–85

vs. information, 92

storyboards, 51, 95, 97, 100–101

storytelling. See also story

digital, 94

learning from masters of, 107

marginalization of, 16

principles, 86–87

visual, 22, 88

surprise, 236

Suzuki, Daisetz, 9, 218

Sweller, John, 10

symmetrical designs, 166–168

symphony aptitude, 17

T- U

Takahashi, Masayoshi, 206

tea ceremony, 115, 121

technology, presentation, 11, 260

TED

archives, 246

conference, 12, 13, 243, 246

events Web site, 286

templates, 46, 100, 141, 143, 175, 209

text size, 244

time constraints, 39, 128, 246, 248–249

time-saving features, software, 128

Toastmasters, 286

Toogood, Granville N., 236

transitions, 20, 61

Tufte, Edward, 134, 140

Turner, Mark, 16

Ueland, Brenda, 35, 219

Understanding Comics, 125

unexpectedness, 78, 79, 125, 236, 270

Universal Principles of Design, 144

V- W

video, power of online, 12

Visual Explanations, 134

visual literacy, 22

visuals

bilingual, 158–159

characteristics of good, 187

power of, 144–147

sample, 187–208

visual storytelling, 88

Wabi Sabi Simple, 42

wabi-sabi simplicity, 121–122, 125

Wabi-Sabi Style, 120

Webinar Smarts, 262

Weismann, Jerry, 100

whiteboards, 50–51, 95, 267

white space, 161–171, 185

Whole New Mind, A, 14, 19

Why Business People Speak Like Idiots,

253

Williams, Robin, 133, 177

wizards, 46

Y- Z

You’ve Got to Be Believed, 244

Zander, Benjamin, 225, 226–227, 228,

278

Zander, Rosamund, 225, 228

Zen

aesthetic values, 117–122, 119

and art of connection, 232–233

and art of mindfulness, 215–216

and attentiveness, 248

and beginner’s mind, 33–35

and empty space, 161

and judo principles, 223–224

Presentation (See Presentation Zen)

and professional communications, 7

and self-imposed constraints, 39–42

and simplicity, 115–116, 125

and Steve Jobs, 117–118

Zen and Japanese Culture, 218

Zen of Creativity, The, 140