Guideline

Supply Chain Management

in Electronics Manufacturing

German Electrical and Electronic Manufacturers’ Association

Impressum

Guideline

Supply Chain Management in Electronics Manufacturing

Published by:

ZVEI - German Electrical and Electronic

Manufacturers’ Association

Electronic Components and Systems Division

PCB and Electronic Systems Division

Lyoner Straße 9

60528 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Phone: +49 69 6302-267

Fax: +49 69 6302-407

E-mail: [email protected]

www.zvei.org

Responsible: Bernd Künstler, ZVEI

Editorial team:

Hans Ehm, Inneon Technologies

Tom Effert, Leopold Kostal

Daniel Geiger, Siemens

Simon Geisenberger, Osram Opto Semiconductors

Ernst Kastenholz, Zollner

Klaus Neuhaus, Sanmina-SCI

Lars Pötzsch, Harting Electronics

Dirk Rimane, Sasse Elektronik

Manuela Zeppin, Inneon Technologies

Michael Ginap, Avineo

Christian Schober, Schober Unternehmensentwicklung

Editor: Laura Korfmann, Inneon Technologies

And many other representatives of member companies of the ZVEI, whose

names are listed in the Appendix.

Critically reviewed by Alexander Florczak, Robert Bosch, Helmut Heusch-

neider, Continental Automotive, Prof. Dr. Klaus-J. Schmidt and Jörg Kuntz,

AKJ Automotive and Dr.-Ing. Holly Ott, TUM School of Management.

November 2014

While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this document,

ZVEI assumes no liability for the content. All rights reserved. This applies in

particular to the storage, reproduction, distribution and translation of this

publication.

Guideline

Supply Chain Management

in Electronics Manufacturing

German Electrical and Electronic Manufacturers’ Association

4

Foreword 8

1 Supply Chain Management –

Definition, Fundamentals, Standards

10

1.1 Dening supply chain management 10

1.2 SCOR

®

model 11

1.3 Skilled workforce along the supply chain 12

1.4 Overview of supply chain management standards 13

1.4.1 Selection of different strategies 13

1.4.2 Levels of supply chain design 14

1.4.3 Supply chain controlling KPIs 15

1.4.4 Supply chain interfaces 16

1.4.5 Identication and packaging 16

1.4.6 Supply chain management cost factors 16

1.4.7 Future requirements for standardised and

ad-hoc communication processes 17

2 Robust Supply Chains with High

Responsiveness and Flexibility

18

2.1 Measuring and increasing exibility 18

2.1.1 Denition of exibility 18

2.1.2 Triggers demanding greater exibility 19

2.1.3 Guideline for measuring and increasing exibility 19

2.2 Measuring and increasing responsiveness 21

2.2.1 Denition of responsiveness 21

2.2.2 Measuring responsiveness 21

2.2.3 Guideline for measuring and increasing

responsiveness 21

2.3 Measuring and increasing forecast accuracy and measuring

and reducing the bullwhip effect 23

2.3.1 Denition of the bullwhip effect 23

2.3.2 Denition of forecast accuracy 25

2.3.3 Measuring forecast accuracy 25

2.3.4 Guideline for measuring and increasing

forecast accuracy 26

2.3.5 Guideline for measuring and reducing the

bullwhip effect 26

2.4 Meaning of a robust supply chain 27

2.5 Denition of a robust supply chain 28

2.6 Development of a robust supply chain 28

2.6.1 Risks to the individual areas 28

2.6.1.1 Design 29

2.6.1.2 Plan 29

Table of Contents

5

2.6.1.3 Source 30

2.6.1.4 Make 30

2.6.1.5 Deliver 31

2.6.1.6 Tabular risk summary 32

2.6.2 Safeguarding areas against risks 33

2.6.2.1 Design 33

2.6.2.2 Plan 34

2.6.2.3 Source 35

2.6.2.4 Make 37

2.6.2.5 Deliver 41

2.6.3 Organisation 42

2.7 Supply chain checklist/questionnaire 44

2.8 Conclusion to robust supply chains with a high level

responsiveness and exibility 46

3 External Framework Conditions 47

3.1 Export control 47

3.2 Customs law 48

3.2.1 Authorisations and simplied procedures 49

3.2.2 Tariff classication 49

3.2.3 Origin of goods 50

3.2.3.1 Non-preferential origin of goods 50

3.2.3.2 Preferential origin of goods 50

3.2.4 Authorised economic operator (AEO) 51

3.2.5 ATLAS 52

3.2.6 Movement of goods during business travel 53

3.3 Statistics (intrastat/extrastat) 53

3.4 Taxes 54

3.4.1 Recapitulative statements 54

3.4.2 Certicate of entry 55

3.4.3 Special case: chain transactions 56

3.4.3.1 Intra-Community triangular transactions 56

3.4.3.2 Indirect exports 56

3.4.4 Special case: consignment warehouse 57

3.5 Trafc/transport/services 58

3.5.1 Incoterms

®

58

3.5.2 Known consignor 59

3.5.3 Cargo securing/lorry 60

3.5.4 Transport of dangerous goods 61

3.5.5 Consular and model rules 61

3.6 Compliance/ethics/environmental protection 62

3.6.1 Social responsibility 62

3.6.1.1 ZVEI Code of Conduct 62

6

3.6.1.2 United Nations Global Compact 62

3.6.1.3 Conict minerals 63

3.6.2 Directives and regulations of the European Union 63

3.6.2.1 RoHS directive 63

3.6.2.2 ELV Directive 64

3.6.2.3 REACH Regulation 64

3.7 Conclusion on external framework conditions 65

4 Supply Chain Management

Education and Training

66

4.1 Process-oriented skills management 67

4.2 Hot spots for skills development 69

4.2.1 Enterprise survey as departure point 69

4.2.2 How to use the one-page guides 69

4.2.3 Sales planning and forecasting 71

4.2.4 Customs and international trade 72

4.2.5 Simulation-based optimisation 74

4.2.6 Vendor managed inventory (VMI) 76

4.2.7 EDI classic and WebEDI 78

4.2.8 Tracking and tracing 80

4.2.9 Process organisation 82

4.2.10 Shipment guidelines 84

4.2.11 Consignment 86

4.2.12 Goods labelling 88

4.2.13 Kanban 90

4.3 Education, training and skills development 92

4.3.1 Situation and need for action 92

4.3.2 Training and education pathways 92

4.3.3 Initial vocational training in the dual system 93

4.3.3.1 Room for manoeuvre in general training plans 93

4.3.3.2 Supply chain management content in general

training plans and framework curricula 93

4.3.3.3 Case study: Zollner Elektronik – supply chain

management training scheme 95

4.3.4 Degree courses at institutions of higher learning 96

4.3.4.1 Key courses of study in the supply chain

management area 96

4.3.4.2 Degree programmes offered in logistics 96

4.3.4.3 Analysis of degree course content 96

4.3.4.4 Conclusions for ongoing course development –

more focus on process-orientation 96

4.3.4.5 Implementation of supply chain management

study modules 97

4.3.5 Advanced vocational training 97

7

4.3.5.1 Key advanced vocational training courses in the

supply chain management area 97

4.3.5.2 Supply chain management – related content in

individual courses of study 97

4.3.5.2.1 Bachelor professional of management for industry 97

4.3.5.2.2 Master professional of technical management (CCI) 98

4.3.5.2.3 Bachelor professional of freight transport and

logistics (CCI) 98

4.3.6 Continued training and education 98

4.3.6.1 Continued education and training opportunities

in the supply chain management area 98

4.3.6.2 Suggestion from an industry perspective:

development of a certicate course in supply

chain management 99

4.3.7 Company training 100

4.3.7.1 Continuing education and training programmes 100

4.3.7.1.1 Case study: company training at Inneon 101

4.3.7.1.2 Case study: company training at Osram Opto

Semiconductors 102

4.3.8 Continued education and training in processes 103

4.4 Conclusion on education and training in supply chain

management 106

5 Appendix 107

5.1 Participating companies and individuals 107

5.2 List of abbreviations 111

5.3 Symbols 117

5.4 Figures 117

5.5 Tables 122

5.6 Bibliography 123

5.7 Customs and foreign trade guide (long version) 125

8

Foreword

Globalisation creates opportunities for faster

development and production. Thanks to mod-

ern communication devices, these opportu-

nities can now be exploited. The exible use

of global manufacturing capacities, com-

bined with a focus on core competencies, is

key to maintaining a sustained competitive

advantage in today’s business environment.

However, this capability requires increasingly

complex supplier networks, which must be

controlled and optimized to provide reliable,

fast and exible services.

ZVEI members also increasingly recognise the

importance of an optimal organisation of sup-

plier networks. Although this topic is equally

important for all segments of the electron-

ics industry, the initiative to set up a Supply

Chain Management (SCM) working group

and to draft this white paper was originally

launched by the ZVEI Electronic Components

and Systems Division and PCB and Electronics

Systems Division. These companies are located

upstream in the electronics value chain and

thus face higher variability and disruption risk.

As it is difcult to forecast the sales volumes

of end products, the upstream companies are

required to maintain high exibility and fast

reaction times (responsiveness). Additionally,

supplier structures are becoming increasingly

global and increasingly subject to natural dis-

asters, political upheavals and transport risks,

as well as a wide variety of individual trade

and customs regulations.

Since these challenges must be addressed

by people, organisations, processes and IT

systems, the availability of experienced and

skilled staff is one of the key success factors of

an optimised supply chain.

With this in mind, the ZVEI working group

‘Supply Chain Management in Electronics

Manufacturing’ was constituted in April 2013

to collaborate in providing recommendations

for companies that help them to better under-

stand value networks, determine their ideal

design and prepare them for future chal-

lenges. This paper focuses on the availability

of electronics components in the supply chain

for high value products such as vehicles, air-

planes, machines, industrial goods, process

systems, power plants, hospitals, medical

products, etc. In addition to the primacy of

availability, it also discusses aspects of supply

chain efciency.

The ndings have been summarised in this

industry recommendation, which in addition

to sharing expert knowledge, also suggests

courses of action and provides checklists and

best practices.

The paper examines the following topics:

• Supply chain management – denition,

fundamentals, standards

• Robust supply chains with high responsive-

ness and exibility

• External framework conditions

• Supply chain management training pro-

grammes

This white paper does not claim to be exhaus-

tive, but offers useful reference and guidance.

Every company has its own size, focus and

position and thus different levels of maturity

in supply chain management. This white paper

is based on the knowledge and expertise of

more than 80 supply chain experts from dif-

ferent companies and thus provides a sound

knowledge base for all industries with a spe-

cial focus on the electronics industry.

9

Since supply chains are also subject to con-

stant change and adaptation processes, this

document reects the current status of the

aggregated view of the participating compa-

nies. More information on updates, new docu-

ments and upcoming events can be found on

the ZVEI website. Moreover, discussion groups

and working group meetings encourage the

exchange of knowledge and experience.

We wish our readers much success in design-

ing and optimising their supply chain pro-

cesses and hope this paper provides useful

support.

Editorial team

Frankfurt am Main, November 2014

10

1 Supply Chain Management –

Denition,Fundamentals,Standards

This chapter rst claries the denition of

supply chain management and discusses the

fundamentals of the SCOR

®

model, as well the

requirements for skilled staff. Finally an over-

view of supply chain management standards

is provided.

1.1 Deningsupplychainmanagement

The term ‘supply chain’ refers to a network

of organisations involved in generating value

for the end customer in the form of products

and services via upstream or downstream

links in different processes and activities.

1

In

an industrial enterprise, the delivery of input

materials marks the starting point of a supply

chain, while the supply of nished material to

the customer marks the ending point.

Business processes are becoming increasingly

complex as a result of growing market globali-

sation. Additionally, to save costs and increase

responsiveness, companies are under constant

pressure to optimise their production and sup-

ply chains.

With competition becoming increasingly

erce, price, quality and functionality are

no longer the sole key deciding factors for

a purchase decision. Flexibility, speed and

customer satisfaction have also become top

priorities. This can be achieved by improving

the service and customising products to meet

specic requirements. The success factor time

1 Christopher, 1998

(meaning to be fast) describes the necessary

adaptation of companies to changing compe-

tition and market conditions.

In short, the demands placed on companies

and supply chain management have multi-

plied, necessitating greater exibility within

the supply chain,

2

and companies that fail to

adapt in time to the changing conditions face

substantial disadvantages in terms of prota-

bility and long-term competitiveness.

3

2 Blecker and Kaluza, 2000

3 Beckmann, 2004

DELIVER

RETURN

RETURN RETURN

SOURCEDELIVER

PLAN

MAKE

PLANPLAN

RETURN

RETURN

RETURNRETURN

MAKE

DELIVER

SOURCE

RETURN

MAKE

Supplier

Internal or External

Customer

Internal or External

Customers'

Customer

Suppliers'

Supplier

SOURCE

DELIVER

SOURCE

RETURN

Your Organisation

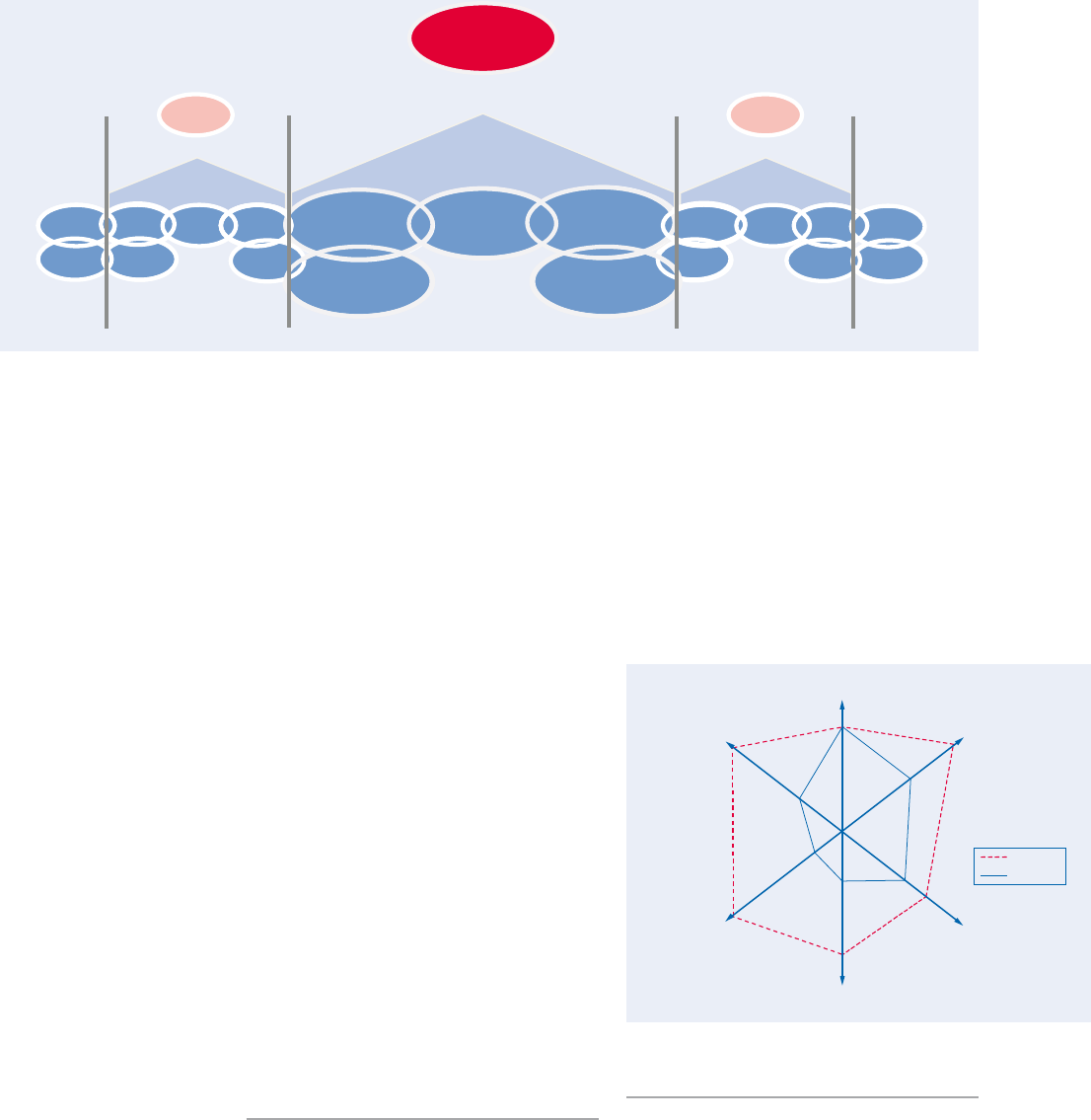

Figure 1: Supply chains extend from the supplier’s supplier to the customer’s customer (SCOR

®

model) (Copyright Osram OS)

Figure 2: Development and importance of strategic success factors

(based on Blecker and Kaluza, 2000) (Copyright ZVEI)

now

before

Service

Costs

Quality

Individualisation Functionality

Time

11

„The supply chains of best practice compa-

nies are nearly twice as fast as the average!“

(Prof. Dr. Wildemann)

1.2 SCOR

®

model

This recommendation (Supply Chain Manage-

ment in Electronics Manufacturing) is based

on the current 2012 version 11.0 of the

SCOR

®

model that was rst developed and

published by the APICS Supply Chain Council

(APICS SCC), a global non-prot organisation,

in 1996, and has been continuously revised

since. The Supply Chain Operations Refer-

ence model (SCOR

®

) is a management tool to

assess and analyse supply chain performance.

SCOR

®

represents a global standard in sup-

ply chain management by providing a unique

framework that determines and links perfor-

mance metrics, processes, best practices and

people’s skills into a unied structure.

4

The

SCOR

®

model can be used to describe the

value chains from the supplier’s supplier to

the customer’s customer and is organised

around the six primary management pro-

cesses – Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, Return

and Enable.

4 APICS Supply Chain Council (SCC), 2014

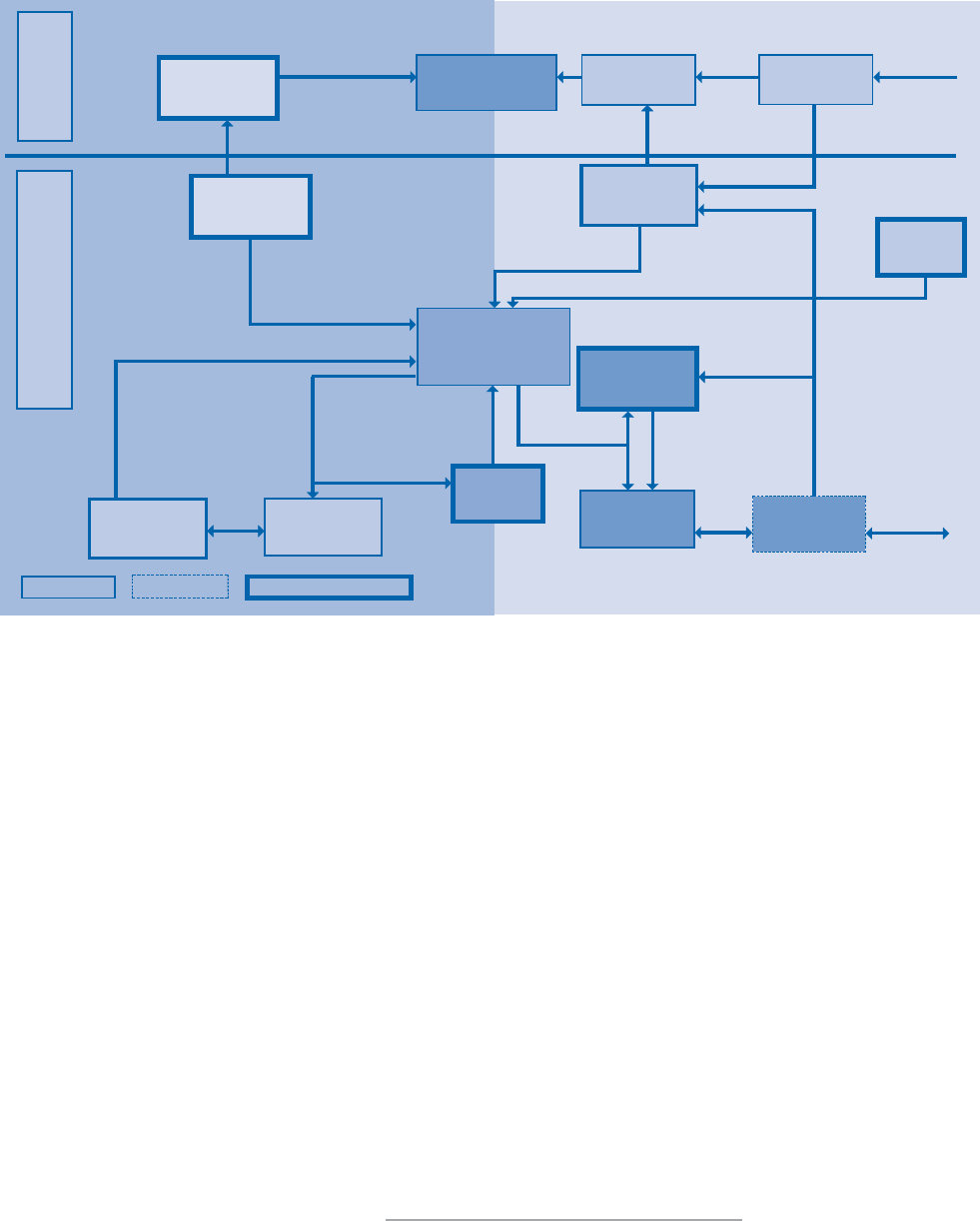

Figure 3 and Figure 4: Supply chain impact

(Copyright Figure 3 Wildemann, Copyright Figure 4 Cohen and Roussel, 2013)

Figure 5: Processes within the SCOR

®

model (Copyright ZVEI)

Plan Plan Plan

Source Source

Source

Make

Make MakeDeliver Deliver

Deliver

Return

Return

Return

Return

Return

Return

Enable Enable

Enable

Supplier

Company

Customer

Companies that use

their supply chains

strategically realize

better business

results than their

competitors

Sales growth

Profitability

Nett asset turns

Percentage of industry average

50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150

50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150

50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150

BICCs

Non-BICCs

BICCs

Non-BICCs

BICCs

Non-BICCs

The impact of supply chain

management stems from the

creation of transparency along

the entire value chain and the

consequent avoidance of informa-

tion asymmetries.

Delivery reliability + 40%

Capacity utilisation + 10%

Delivery time - 30%

CT (production) - 10%

Inventories - 20%

Management expenditure - 15%

Purchasing costs - 20%

Sales costs - 15%

Production costs - 5%

These companies

also achieve better

supply chain perfor-

mance

Delivery performance to commit date (%)

Total supply chain management costs (% of industry TSCMC)

Cash-to-cash cycle time (days)

0 20 40 60 80 100

50 60 70 80 90 100 110

0 20 40 60 80 100

BICCs

Non-BICCs

BICCs

Non-BICCs

BICCs

Non-BICCs

12

The Plan process links demand and supply

activities and coordinates all other processes

within one value-added level or across com-

panies. For example, the Plan instance coor-

dinates scheduling activities of procurement

(Source), manufacturing (Make) or sales order

fulllment (Deliver) and thus ensures smooth

collaboration within a company or along the

entire supply chain.

The Source process combines all activi-

ties related to the procurement of materials

required to meet planned or actual demand. It

also includes operational activities regarding

suppliers and material inspection.

Make refers to the actual manufacturing pro-

cess, i. e. all processes required to manufac-

ture a nished end product from the materials

provided by Source. This also includes repairs

or services.

Transport management and storage of the

nished products are assigned to the Deliver

process, which also covers the receipt of orders

and receivables management.

Teh Return process is the interface to the sup-

plier and refers to the returning of goods or

information.

In addition to the material ow from the

supplier to the customer, the SCOR

®

model

includes an order and the value ow running

in the opposite direction, as well as non-direc-

tional information ows.

Enable processes are not directly assigned to

an instance, but provide the basis (i. e. ena-

ble) the processes Source, Make, Deliver, Plan

and Return. This includes the necessary regu-

latory body, guidelines and conditions such as

performance measurement, risk management,

master data management, human resource

decisions or network planning.

1.3 Skilled workforce along the supply

chain

Supply chain experts and managers should be

capable of understanding and managing sys-

tem and methods knowledge, actual produc-

tion processes as well as material and infor-

mation ows.

This capability requires emotional and social

moderating as well as communication skills,

in addition to problem solving skills, such as

analytic abilities. In other words, supply chain

experts and supply chain managers must be

generalists in their eld of knowledge.

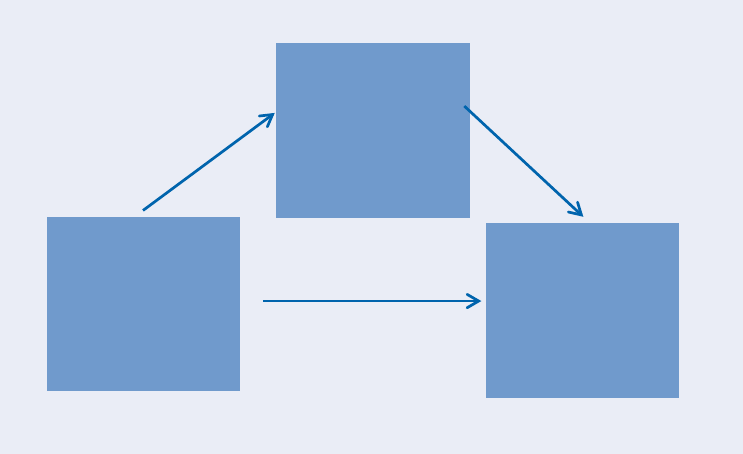

Figure 6: The supply chain is about processes (according to SCOR

®

) relating to material, information and value ows.

(Copyright Inneon Technologies)

Information Flow

Material Flow

Value Flow

Source Make Deliver

Plan

ReturnReturn

Boxes

Bytes

Bucks

13

Supply Chain generalists need to be familiar

with the actual situation and processes along

the supply chain and understand the methods,

organisational forms and tools to be used. A

basic understanding of controlling, business

economics and IT systems, e. g. in ERP (Enter-

prise Resource Planning), APS (Advanced

Planning System), EDI (Electronic Data Inter-

change) and MES (Manufacturing Execution

System) is required.

To ensure the supply of logistics specialists, it

is recommended that external networks be set

up and expanded, collaboration with universi-

ties and associations fostered, and discussions

with educational facilities started concerning

training and study contents. The following list

provides an overview of frequently used meth-

ods to contact potential job applicants:

• awarding project assignments and intern-

ships to potential applicants,

• offering Bachelor’s and Master’s disserta-

tions as well as doctoral theses to students

• employing working students,

• recruiting graduates of logistics and supply

chain studies,

• offering dual track studies to retain stu-

dents in the long term,

• providing on-the-job in-house training and

qualication measures.

Large companies often design their own quali-

cation programmes to introduce staff to sup-

ply chain management and to further provide

training in specic areas. Some companies

even choose to run their own supply chain

academies in order to foster and develop sup-

ply chain talent.

More information on the subject of training

and qualication is provided in chapter 4.

1.4 Overview of supply chain

management standards

This section lists sample approaches intended

to provide an initial overview of the different

strategies, levels of supply chain design, key

performance indicators (KPIs), interfaces, cost

factors and future requirements for communi-

cation processes in supply chain management.

The words written in blue and bold refer to

topics that will be explained and detailed in

the following chapters of this white paper.

1.4.1 Selection of different strategies

The following examples represent a small

selection of the many different SCM strategies

and approaches in place:

• Efcient Consumer Response (ECR) with

logistics components: from vendor/sup-

plier managed inventory (VMI/SMI) and

cross-docking (demand-driven goods dis-

tribution) to synchronised production and

urban production,

• Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

and relationship marketing: continuously

improving customer satisfaction, customer

loyalty and customer acquisition,

• postponement strategies: reducing semi-

nished and nished goods inventories

through delayed differentiation,

• sourcing strategies: single sourcing and

multiple sourcing procuring modules/sys-

tems from system suppliers (modular/sys-

tem sourcing) and developing the market

by systematically expanding the procure-

ment policy to international sources (global

sourcing),

• production and procurement strategies:

Kanban with just-in-time production sys-

tems (JIT) / just-in-sequence (JIS) produc-

tion systems, consignment, indicators of

progress to provide transparency by closely

linking the supplier and customer and man-

aging the collaboration via call-off orders

and JIT delivery schedules, etc.,

• supplier management: qualication, pur-

chasing, logistics, quality,

• electronic marketplaces: as platforms for

the commercial exchange of goods and ser-

vices and the option of selling products at a

certain time and place,

14

• inter-organisational collaboration: includ-

ing the creation of between legally inde-

pendent partners within the network of a

supply chain via the Internet,

• virtual freight exchanges: to improve ship-

ping capacity utilisation and reduce ship-

ping costs, tracking and tracing (external/

internal) to monitor shipments, e-auctions,

etc.,

• disposal and recycling strategies: which

should also be mentioned for the sake of

completeness.

1.4.2 Levels of supply chain design

In order to assess the different levels of supply

chain design, it is necessary to rst explain

possible approaches or methods to supply

chain management before going into more

detail on the various tools.

Methods

Many companies design their supply chains

by rst introducing and applying general

approaches to SCM and subsequently resolv-

ing the process issues.

The rst SMC approaches to be implemented

in-house often include lean processes and

continuous improvement processes (CIP), time

management methods (‘Arbeitsablauf-Zeit-

analyse’, AAZ) such as methods-time meas-

urement (MTM) or REFA (methods of the Ger-

man REFA Association for Work Design/Work

Structure, Industrial Operation and Corporate

Development) and value stream optimisation

and design and improving process ows.

The following approaches are used in-house

and across companies focusing on the cus-

tomer and/or supplier: design for manufac-

turing (product, process and logistics-related)

and design for testability, design to cost, etc.

In addition, digital or cross-linked factories

and simulations are introduced as well as

inter-company comprehensive value stream

design from the customer (or customer’s cus-

tomer) and the company’s own production to

the supplier/distributor/manufacturer.

The methodology introduced with the SCOR

®

model in the mid-90s has proved to be reliable

for the practical analysis and design of supply

chains and can also be used for the strategic

coordination of the aforementioned methods

thanks to its top-down approach. This meth-

odology has only recently been expanded to

include the ‘Management for Supply Chain’

(M4SC) concept.

The idea of supply chain segmentation plays

a major role in supply chain design and opti-

misation. In this context, a supply chain can

be understood as a well-dened value stream

that combines products/services and custom-

ers/markets. Supply chain segmentation thus

connects product and market segmentation.

The aim of supply chain segmentation is to

align separate supply chains to the strategic

business requirements in order to avoid a one-

size-ts-all approach to performance manage-

ment and control. Consequently, supply chain

segmentation is essential in establishing

supply chain management as a control tool

aligned to the relevant market requirements.

SCM tools

This section lists the most common SCM tools

according to their relevant application area

and does not claim to be exhaustive.

15

Two commonly used tools to reduce inventory

are inventory decomposition using ABC/XYZ

analyses and stock coverage and inventory

turnover analyses. By analysing the inventory

range, items can be classied in fast movers

(<3 months), moderate movers (3-12 months)

and slow movers (>12 months).

Cycle time and set-up time analyses are also

extensively performed to understand time

losses. Electronic tools are frequently used

to improve inventory control and reduction:

eKanban, min-max control, C item manage-

ment, etc. Additionally, strategic partnerships

are often established between supplier and

customers to improve inventory management,

including consignment and VMI.

The following SCM tools are used, among

others, to reduce shipping costs: system-sup-

ported shipping requests, automatic shipping

cost calculation, self-billing processes, sum-

mary invoices, standard and returnable pack-

aging, milk runs and round trips, hubs (inter-

nal/external), cross-docking (demand-driven

goods distribution), freight pooling, shipping

guidelines, etc.

For IT support the following tools are wide-

spread in today’s industry: EDI and WebEDI,

barcodes (2D, data matrix, etc.), RFID, BI

(databases; data warehouses), ERP and MES

systems, CAx systems, electronic work ows,

alternative stocktaking procedures, inter-

nal tracking and tracing, comprehensive

traceability, etc.

Accurate, timely and useful information is

essential to effective and optimized supply

chain management, and therefore many com-

panies use internet portals or supply chain

‘cockpits’ to disseminate critical supply chain

information (order statuses, inventories,

inventory ranges, etc.). Additionally, sharing

supply chain information can be dissemi-

nated effectively through the internet, using

e-Learning modules, computer-aided train-

ing, and internal Wikis.

1.4.3 Supply chain controlling KPIs

Supply Chain key performance indicators (KPI)

are used to measure the performance and

quality of a supply chain. Although KPIs need

to be viewed from within their own context,

their importance increases when compared to

a company’s own or external business data.

Examples of KPIs and other aids (results-ori-

ented and time-limited):

• Sourcing KPIs:

delivery times, price trends according to

commodity groups, etc.,

• Planning KPIs:

forecastaccuracyandexibility,

• Warehousing KPIs:

warehouse inventory, inventory turnover

factor, inventory range, etc.,

• Production KPIs:

utilisation rates of business divisions (pro-

duction facilities), cycle times, set-up

times, etc.,

• Distribution KPIs:

orders in hand including forecasts, order

backlog, invoice backlog, total sales/sales

by business division, etc.,

• Financial process KPIs:

productivity and protability KPIs, etc.,

Non-quantiable data, e. g. employee know-

how, is difcult to express in gures. Since

KPIs are determined at a certain point of time

and are therefore static, they should be speci-

ed promptly with the process ows.

16

Additionally, KPIs provide information on the

‘what’ and ‘where’, but not on the ‘how’. They

neither indicate how they have been compiled

nor how to proceed.

The SCOR

®

model provides guidance in this

matter with standardised KPIs in a clear

structure: the KPIs (metrics) are organised in

a hierarchical structure according to perfor-

mance attributes, and they are assigned to the

relevant processes.

The strategic metrics form the top level of

the hierarchical structure. They help compa-

nies translate their strategies to supply chain

strategies. Below the strategic metrics, there

are the diagnostic metrics and, at the low-

est level, the root-cause metrics. The SCOR

®

model denes more than 500 metrics.

1.4.4 Supply chain interfaces

Supply chain interfaces are becoming more

important/critical with increased outsourcing

and globalization. Information on this subject

is detailed in the guideline issued by the ZVEI

working group ‘Traceability’.

Various identication labels serve as inter-

faces between the supply chain stages. Stand-

ardised labels such as MAT labels, GTL

(Global Transport Label for outer packaging)

VDA labels and delivery information in paper

form (e. g. shipping documents) or electronic

form (dispatch notication or EDI messages).

The electronic data interface supports the

sharing of information, ranging from plan-

ning and forecast data, inventory/require-

ments overviews, contracts and orders, order

conrmations and invoices to delivery notes

and delivery status information.

1.4.5 Identicationandpackaging

As a result of increasing cross-company stand-

ardisation, the various identication labels

can again be named as examples here, espe-

cially MAT labels for inner packaging and GTL

for outer packaging, the latter serving also as

a master label.

These labels almost always include barcodes

to enable automatic recording of data con-

tent. RFID labels are also increasingly used

and contain a passive antenna for touch-free

data reading and processing in addition to the

barcode and plain text.

Packaging is also increasingly subject to

standardisation – from standardised box for-

mats to reusable packaging and containers.

1.4.6 Supply chain management cost

factors

Various costs may incur in supply chain man-

agement. Examples of some of the most fre-

quently occurring aspects are given below:

• costs incurring from insufcient speed,

especially when it concerns semiconductor

products or semiconductor-enabled prod-

ucts. According to Moore’s Law

5

und More

than Moore

6

some semiconductor products

5 Moore, 1998

6 Zhang and Roosmalen, 2009

Performance Attribute Denition Strategic SCOR

®

-

Metric (Examples)

Reliability Ability to perform tasks as

expected

Perfect order fulllment

Responsiveness Speed at which tasks are

performed

Order fulllment cycle time

Agility Ability to respond to

marketplace changes in the

supply chain

Upside supply chain exi-

bility

Cost Costs associated with oper-

ating the supply chain

Total cost to serve

Assets Effectiveness in managing

assets (xed and working

capital) in the supply chain

Cash-to-cash cycle time

Table 1: Examples of strategic SCOR

®

model metrics (Copyright ZVEI)

Figure 7: Barcodes facilitate quick and easy reading of the

corresponding data. (Copyright Escha)

17

can be produced at increasingly lower cost,

thus losing value,

• logistics costs (shipping, handling, supply

channels, calculations, etc.),

• employment costs,

• costs incurring from the scrapping of goods,

especially in the event of short product life

cycles and inaccurate forecasts,

• costs incurring from a company’s own

inventories (in-house, consignment),

• packaging costs,

• infrastructure costs (storage facilities, IT

equipment such as manual devices, PDAs,

WLAN coverage, software), external service

providers, etc.),

• insurance costs, taxes, customs, mis-

declaration (e. g. wrong class of goods),

export controls, etc.,

• certicationcosts (e. g. through the Ger-

man Federal Aviation Ofce (LBA) for air-

freight security, authorized economic oper-

ator (AEO), etc.),

• costs for capacity and exibility provision

(storage, production, shipping capacity,

late diversication, scrapping, sales plan-

ning, etc.),

• costs resulting from special activities such as

special deliveries, interim inventories, etc.,

• costs resulting from a lack of standards,

• costs incurring from complaints and

returned shipments,

• costs incurring from sample management,

• costs caused by missing process synchroni-

sation,

• incidental costs (planning provisions, con-

tingencies, sub-optimisation).

1.4.7 Future requirements for standard-

ised and ad-hoc communication pro-

cesses

Rolling sales forecasts transmitted from the

customer in dened formats and intervals are

prime examples of requirements for stand-

ardised communications process. The fore-

casts should be internally discussed in S&OP

(Sales & Operations Planning) meetings and

incorporated into the production and order

planning derived from this data. It is recom-

mended that this process be standardised,

systematised and conducted on a regular

basis (see VDA Recommendation 5009 for the

automotive industry). Forecast accuracy is of

the essence. The better a forecast, the more

downstream processes can be run automati-

cally.

In addition to preventive measures such as

increased inventories, production exibility

(short cycle times) and exible assembly lines

in terms of the products to be produced

7

, sce-

nario planning will be increasingly requested

in the future. Scenario planing yields, differ-

ent results depending on the business and

production conditions. With information from

scenario planing, companies would be able to

respond quickly and specic to different sit-

uations.

Against the backdrop of increasing volatility,

staff and IT-supported ad hoc communication

will play an increasingly important role. Com-

munication is essential, especially in the event

of a crisis. However, it is equally important to

dene control limits with thresholds trigger-

ing an alarm for action.

7 VDA-Projektgruppe ‘Programm- und Produk-

tionsplanung’, (2008)

18

As explained in chapter 1, supply chains are

becoming more and more complex due to the

increasing number of company and country

networks as globalization increases.

The ability of companies to adapt to chang-

ing competitive and market conditions is a

key success factor. Supply chains need to be

highly exible.

8

Another critical factor is the

responsiveness of the supply chain, since this

greatly inuences the exibility and customer

satisfaction. Supply chain processes can be

optimised in this context with high forecast

accuracy and by reducing the bullwhip effect

(see chapter 2.3.1 for denition).

The robustness of a supply chain is another

core element of successful supply chain

management. The supply chain design must

ensure that they are able to withstand disrup-

tions and risks. Consequently, comprehensive

risk management plays a major role in safe-

guarding the supply chain.

The following chapter provides an overview of

the design and control of a supply chain’s cen-

tral success factors: exibility, responsiveness,

forecast accuracy and robustness.

The information provided below is based on

the SCOR

®

modell (chapter 1.2).

2.1 Measuring and increasing

exibility

Prior to presenting a guideline for measuring

and increasing exibility, it is necessary to

rst dene exibility and to identify the trig-

gers requiring greater exibility.

8 Blecker and Kaluza, 2000

2.1.1 Denitionofexibility

“The more human beings proceed according

to plan, the more effectively they may be hit

by coincidence.” (Friedrich Dürrenmatt)

Although the concept of exibility is gaining

importance, there is no clear denition of the

term. The speed at which companies adapt to

a new external situation is one part of ex-

ibility, as are the resources employed. Costs

incur both from unused exibility or the lack

of exibility.

9

We dene exibility as follows:

Flexibility is the ability of supply chains or

supply chain companies to adapt to changes

within an appropriate time frame and at a cor-

responding cost.

10

According to the SCOR

®

modell, the concept

of exibility can be subdivided as follows:

• Plan exibility includes processes and

methods.

• Source exibility groups production goods

and production procedures.

• Make exibility maps factory and plant

capacities.

• Deliver exibility deals with demand and

shipping.

Flexibility is broken down into internal

and external exibility. Internal exibility

describes internal company processes and

external exibility describes the adaptability

of a cross-company supply chain. It is also

possible to classify the concept in terms of the

planning horizon, i. e. in operational and stra-

tegic exibility.

The following observations focus on internal

and operational possibilities to measure and

increase exibility.

9 Günthner, 2007

10 Simchi-Levi, Kaminsky, Simchi-Levi and

Bishop, 2007

2 Robust Supply Chains with High

Responsiveness and Flexibility

19

2.1.2 Triggers demanding greater

exibility

A survey has been conducted among ZVEI

members to identify the most common rea-

sons for demanding exibility.

11

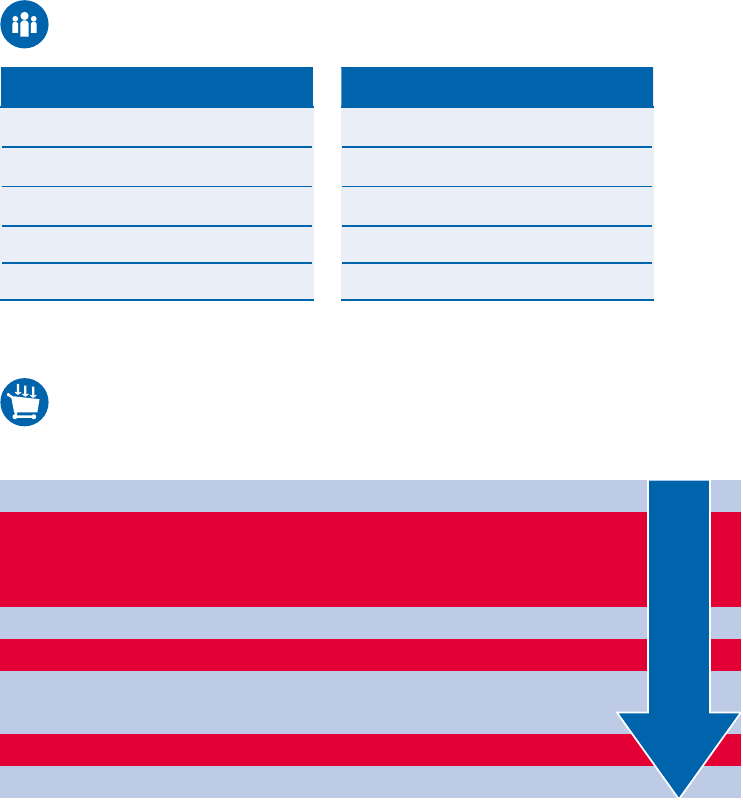

The list above shows the top 10 triggers for

demanding greater exibility in descending

order and assigned to the relevant SCOR

®

pro-

cess. Short-term changes in supply quantities

requested by customers (Plan) are the main

reasons for exibility, followed by the request

for shorter cycle times (Make).

11 Questionnaire sent to 50 members of the

ZVEI SCM working group, response rate 13

2.1.3 Guideline for measuring and

increasingexibility

Although it is difcult to measure exibility

using hard indicators, there are approaches

available that help make company processes

more exible.

The following recommendations for action

have been devised:

• buffer capacities at plants or dened stor-

age spaces before diversication,

• low and exible quantities in the order and

production stages,

• late diversication,

• product and inventory segmentation.

Short-term supply increases present a major

challenge for companies in terms of exibil-

ity. The challenge in this case is to determine

the appropriate amount of free capacities.

Whereas extremely high capacities lead to

high idle time costs, extremely low free capac-

ities may result in orders that cannot be ful-

lled and lead to customer dissatisfaction.

Companies often specify minimum order

quantities to lower their xed production

and administration costs. These measures,

introduced on the grounds of cost efciency,

adversely affect exibility. Flexible order and

production quantities and specifying ship-

ping costs per unit instead of xed lump-sum

freights, both help companies to support more

exible supply chains.

Another obstacle to supply chain exibility is

the increasing customer demand for custo-

misation combined with ever shorter product

life cycles. Postponement strategies are one

approach to resolving this situation. These

can relate to production (assembly postpone-

ment) or logistics (geographic postponement).

Assembly postponement focuses on keeping

products and processes generic for all prod-

ucts as long as possible. As a result, nearly n-

ished products are then nished to meet the

customer’s individual requirements, allowing

the base, generic product to remain as long

TOP 10 – Triggers for Demanding

Greater Flexibility

01 PLAN

Short-term supply volumes

demanded by customer

02 MAKE Cycle time

03 SOURCE

Short-term supply volumes

required from supplier

04 MAKE Production capacity

05 PLAN Inventory

06 DELIVER Delivery date

07 SOURCE Procurement date

08 PLAN Long-term sales forecasts

09 ENABLE

Performance capability of

the identication technology

10 ENABLE IT architecture

Figure 8: Triggers demanding greater exibility in the electronics

industry (Copyright ZVEI)

20

as possible in the production, and thus main-

taining a high level of exibility until close

to the delivery, when the customer demand is

known. In logistics, the postponement strat-

egy refers to the storage of already differen-

tiated products in central distribution hubs.

12

It is recommended that products be catego-

rised according to the order processing strat-

egy, in make-to-stock (MtS) or make-to-order

(MtO) segments. Products that require no

specic customer order to start production

should be manufactured according to the

MtS strategy. It should be possible to forecast

demand for these products as accurately as

12 Pfohl, 2004

possible to ensure they can be sold later. In

the event of low capacity utilisation, the max-

imum stock quantity of these products can be

manufactured until the capacities are required

for other purposes, e. g. for an MtO product.

Thus it is possible to achieve high production

utilisation rates while maintaining high ex-

ibility. The MtO strategy is applied for prod-

uct ramp-up or in the case when it is difcult

or not possible to establish reliable volume

forecasts. The capacity is then utilized only

once an order is received, reducing the risk

of future product scrap. For some industries

it might be advantageous to employ a combi-

nation of MtO and MtS strategies. For exam-

ple, it is often customary in the semiconductor

industry, to make to stock until the ‘Die Bank’,

i. e. as long as all chips are still on one wafer,

and use the MtO strategy from the ‘Die Bank’

onwards.

Decentralised production networks are an-

other option to increase exibility. The aim

of these networks is to localise production on

a regional level, which is particularly useful

in the case of customised products. Decen-

tralized production networks can be achieved

with sustainable manufacturing systems and

application of the relevant logistics, consist-

ing of lean and exible plants through the use

of base products and components, which are

not specic to a particular customer.

Figure 9: IC wafer: Semiconductor innovations enable new prod-

uct launches and product upgrades in ever shorter time frames.

(Copyright X-Fab)

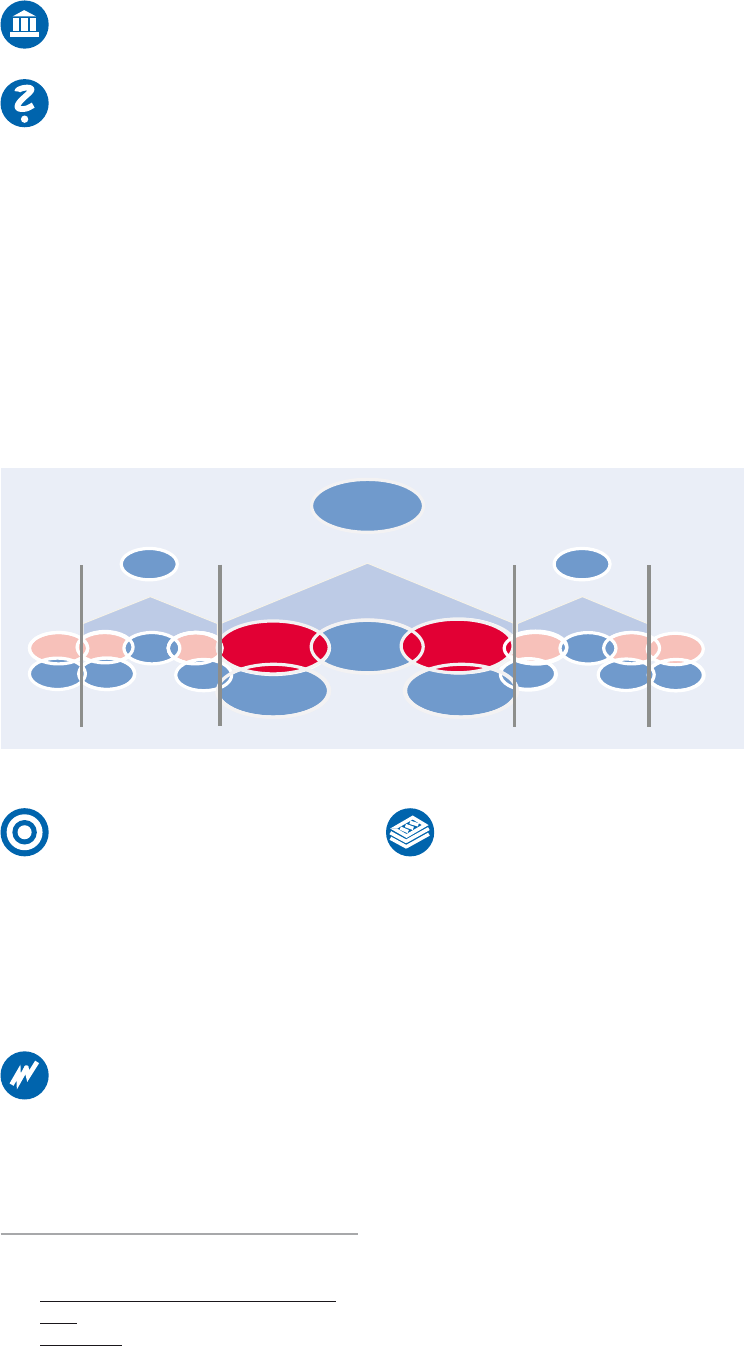

Figure 10: Manufacturing strategies in the semiconductor industry (Copyright Inneon Technologies)

Die Bank

Raw

Material

Supplier

Producer

Tier One

Supplier

OEM

Market

Back-End &

Distribution

centre

Front-End

Make to stock processes Make to order processes

Decoupling point

Delivers to Delivers to Delivers to Delivers to

Orders from Orders from Orders from Orders from

21

2.2 Measuring and increasing

responsiveness

Prior to introducing a guideline for measuring

and increasing responsiveness, it is necessary

to dene the concept of responsiveness and

detail the measurement methods.

2.2.1 Denitionofresponsiveness

In the context of supply chain management,

responsiveness refers to the time required by a

company to adapt to changing requirements,

which can result from a variety of sources,

including product innovation, technological

process or new legal requirements.

2.2.2 Measuring responsiveness

Responsiveness can refer to:

1. Responding to a customer request: The

time measured from receiving the request

to sending the rst information relating to

the fulllment of the request to the cus-

tomer.

2. Meeting the contractually agreed respon-

siveness: The ratio between the orders

completed according to the agreement and

total number of orders served. Although

this KPI does not measure the responsive-

ness itself, but the delivery reliability, it

provides an initial indicator of responsive-

ness.

3. Fullling the customer request: Here,

responsiveness reects the speed and

ability of a company to respond to a cus-

tomer request. The complete fulllment

of the order, at least delivery time and

quantity, is usually considered. To measure

the result, the KPI On-Time In-Full (OTIF)

can be used. This KPI gives the percent

of deliveries which arrive at the customer

according to the customer’s request date

and request quantity.

To compare with a benchmark or the theo-

retically shortest possible reaction the Flow

Factor (FF) can be used. This is dened, in

this context and for this purpose, as the ratio

between the actual responsiveness and the

theoretically shortest possible reaction.

2.2.3 Guideline for measuring and

increasing responsiveness

The Flow Factor concept comes from the sem-

iconductor industry and is calculated as the

ratio of the Cycle Time (CT) to the Raw Process

Time (RPT). In turn, the Cycle Time is derived

from the ratio between Work in Progress (WIP)

and throughput, here referred to as Going

Rate (GR). Inventory refers to the number of

manufacturing units currently in a production

system and Going Rate to the number of units

manufactured per day, for example. The Raw

Process Time is the average time it takes a job

to be processed under ideal conditions, i. e.

excluding queuing times and inefcient pro-

cesses (provided all four partners involved are

fully available: man material, machine and

method). The theoretical optimum Flow Fac-

tor is thus ‘1.0’. Assuming a given variability

(α) combined with a high availability of the

four partners and their synchronisation, a low

value of α enables high process speed and

results in high utilisation rates. Reasonable

ow factors that can be achieved in the semi-

conductor production, range between 2.5 and

3.0 based on 24/7/365 operation.

13

The ow factor is often used in connection

with the operating curve, which uses variabil-

ity (α) to show the variation in the operating

curve for a standard manufacturing process

or for processes in general. Low variability α

indicates few disruptions and high utilization

is possible (Flow Factor approaches 1.0).

13 Hopp and Spearman, 2011

Flow Factor

=

Cycle Time

Raw Process Time

Cycle Time

=

Work in Progress

Going Rate (throughput)

22

Assuming a given going rate (in this exam-

ple 80 percent of the maximum capacity of

the production unit), Figure 11 illustrates that

the blue operating curve has a signicantly

smaller ow factor and thus shorter cycle time

compared to the red curve, consequently indi-

cating a considerable advantage of the blue

production network in terms of responsive-

ness. This method, tried and tested in semi-

conductor manufacturing, can also be trans-

ferred to administrative processes in general.

A key element of a company’s responsiveness

is production cycle time, as responsiveness

necessarily decreases with increasing product

cycle time. Therefore, as a short-term solu-

tion, it is recommended that a limited num-

ber (e. g. 10 percent of the manufacturing

capacity) be reserved for emergency batches

to be able to respond to customer requests

received at short notice or with high priority.

Prioritising production orders can be another

solution for such exceptional situations. How-

ever, for long term cycle time improvement,

one approach can be illustrated with the oper-

ating curve. Low variability α, in other words

small deviation from standard manufacturing

processes, enables the lowest cycle time to be

achieved, i. e. a cycle time approaching the

Raw Process Time.

Another approach to increasing responsive-

ness is the employment of different order pro-

cessing strategies.

As discussed in the section 2.1.3, products

which can be reliably forecasted can be pro-

duced as MtS, with a high capacity utilization.

The buffer stock then can fulll demand when

an MtO product is produced.

Being able to respond quickly to customer

requests is particularly challenging for com-

panies whose products have extensive bills

of materials. The many different component

parts present a higher risk of supply short-

ages and of sources of error, both reducing

responsiveness. Standardising the products

and taking a foresighted approach in contract

negotiations with customers and suppliers

are two options to handling this situation.

Improvements can be achieved, for instance,

with dual/multiple sourcing strategies such

as warehousing strategies coordinated along

the entire value chain and dened accept-

ance periods (frozen windows). The provision

of information at the point of sale within all

levels of the value chain can also contribute to

substantially increasing responsiveness.

Cross-company coordination of the entire

value chain is a major challenge. This is often

due to conicting goals and incentives along

the supply chain. For example, a market-

ing unit may inate its demand forecast to

ensure future supply for potential customers.

If the market does not materialize, these g-

Figure 11: Operating points on two different operating curves (Copyright Inneon Technologies)

Operating

Points

α = 1.47

α = 0.85

FF

FF

1

Capa

GR

Manufacturing Utilization

PU

23

ures are reduced, resulting in misalignment,

miscommunication and mistrust towards the

upstream supply chain stages and contribut-

ing to the bullwhip effect (see section 2.3).

Simulation programmes can be used to gain

an overview of the complete process chain.

Bottlenecks can thus be identied early on,

countermeasures initiated and emergency

plans developed.

Delivery Flow Factor

The Delivery Flow Factor (DFF) has been devel-

oped based on the ow factor. The DFF is the

ratio of the sum of all production jobs con-

rmed completed to the consumption quan-

tities plus the delay regarding the desired

delivery date per organisational unit.

The sum of conrmed and completed produc-

tion jobs completed includes fully or partially

completed production jobs (quantity and/or

process).

The delay regarding the desired date of cus-

tomer orders must also be considered since it

measures the production service not yet sup-

plied.

Supply backlogs of externally procured mate-

rials, e. g. commodities, must not be included.

This calculation approach shows that the

Delivery Flow Factor is an indicator of the

ability of the supply chain management and

production together to respond to changing

market requirements. This suggests that the

Delivery Flow Factor is more focused on pro-

duction (control).

In addition to the Delivery Flow Factor, it is

recommended that the replenishment lead

time and inventory coverage for in-house

produced items be considered, in order to

highlight possible interdependencies between

these two indicators. The ideal situation is

reached when DFF = 1.0. In this case, the

output of the production areas equals the

required consumption data for all levels of

the BOM to meet customer demands without

affecting the inventory structure of the organ-

isational unit (see gure). The dependency is

reected in the fact that inventories must be

increased or decreased if/when DFF ≠ 1.0.

The data required for the calculation is deter-

mined on the basis of database evaluations.

2.3 Measuring and increasing forecast

accuracy and measuring and reducing

the bullwhip effect

Prior to introducing guidelines for measur-

ing and increasing forecast accuracy and for

measuring and reducing the bullwhip effect,

the concept of bullwhip effect and forecast

accuracy must rst be dened and fore-

cast accuracy measuring methods must be

explained in detail.

2.3.1 Denitionofthebullwhipeffect

The bullwhip effect refers to ‘the phenome-

non where orders to the supplier tend to have

larger variance than sales to the buyer’.

14

The

information exchanged with regard to orders

is increasingly distorted as it travels upstream

in the supply chain. The reasons for the devel-

opment of the bullwhip effect in supply chains

can be divided into operational and behav-

ioural causes.

14 Lee, Padmanabhan and Whang, 1997

Delivery Flow Factor

=

Sum of all production jobs confirmed completed

Sum of consumption quantities plus delay regarding the desired delivery date

Figure 12: Delivery Flow Factor (Copyright ZVEI)

Confirmed and Completed

Production Jobs

Confirmed and Completed

Production Jobs

Confirmed and Com-

pleted Production Jobs

Inventory

Inventory

Customer

Requirement

Customer Requirement

Customer Requirement

Flow Factor

> 1

< 1

24

According to Lee

15

, there are four different

operational causes:

• demand signal processing,

• rationing and shortage gaming,

• order batching,

• price uctuations.

Demand signal processing describes the sit-

uation that the original customer demand is

distorted and delayed due to long lead times

between the individual company orders along

the supply chain and incorrect order volume

interpretation by downstream participants.

When demand exceeds supply, rationing and

shortage gaming occurs. Companies pass

on orders to their upstream suppliers that

are greater than the actual orders they have

received. The aim is to receive a larger portion

of the limited supply.

15 Lee, Padmanabhan and Whang, 1997

Order batching results from the various ware-

housing and storage strategies of companies

resorting to material requirements planning

(MRP), enterprise resource planning (ERP) or

advance planning systems (APS). These sys-

tems are usually based on monthly or weekly

planning cycles and issue orders at similar

times. Consequently, the majority of orders

are issued weekly/monthly, i. e. within a short

time window. Fixed order and shipment costs

or minimum order quantities – although often

necessary and reasonable – are another rea-

son for combining orders and thus further dis-

torting the original demand signal.

The fourth cause of price uctuations refers

to demand distortion by granting discounts to

drive up sales gures, for example. Due to the

periodic discounts, customers buy more than

they need and stock the excess quantity. As a

result of these additional orders, demand is

further distorted since less is ordered in the

subsequent periods than the actual demand.

Figure 13: Risks spring from unlinked supply chains – the bullwhip effect (Copyright Inneon Technologies)

Bullwhip Effect

Overshooting in

the Value Chain

Customer

OEM Tier 1 Tier 2

Semi-

conductor

Equipment

supplier

Red Line: WSTS

Forecast

Growth Rates y/y: 1997:1Q – 2014:4Qe

-50%

-40%

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

-5%

-4%

-3%

-2%

-1%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Q

1Q

2Q

3Q

4Qe

1Qe

2Qe

3Qe

4Qe

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

World Semi [ToMM] market Growth

[y/y%]

World Economy, Real GDP Growth

[y/y%]

Orange Line: IHS

25

Nienhaus

16

observed the behavioural causes

when analysing the behaviour of the players

participating in the beer distribution game.

The rst behaviour, also referred to as safe

harbour strategy, describes the participants’

aim to create safety stock in order to prevent

bottlenecks and shortages. Thus, participants

place larger orders than they need and thus

articially inate demand.

The second pattern observed is the panic

strategy: participants manage their stock slop-

pily until it falls below a dened safety level.

In this case, they panic when receiving more

orders, which is reected in the signicantly

higher number of orders they issue. Conse-

quently, the demand signal is not correctly

passed on at any time.

The bullwhip effect is well documented and is

a wide-spread phenomenon in supply chains.

16 Nienhaus, Ziegenbein and Schönsleben,

2006

2.3.2 Denitionofforecastaccuracy

Forecast accuracy is the ability to forecast as

accurately as possible demand and demand

development of a customer or market segment

for a product or product group High forecast

accuracy is essential for creating efcient sup-

ply chains and preventing the bullwhip effect.

2.3.3 Measuring forecast accuracy

To continuously improve forecasts, metrics

are required that help analyse the planning

data. There is a wide variety of complex and

less complex metrics available for companies

to employ. This paper explores the two most

popular metrics and their interpretation.

The rst metric is the Mean Absolute Per-

centage Error (MAPE), which is the arithmetic

mean of the absolute deviation of the forecast

from the actual customer orders received in

relation to the actual demand. MAPE is thus

easy to calculate and can be intuitively inter-

preted.

For other analyses, the Symmetric Mean Abso-

lute Percentage Error (SMAPE) can be used.

Although it is more complex to determine

and its interpretation is less intuitive, SMAPE

is more stable in terms of demand distortion

caused by individually occurring major devia-

tion periods.

Figure 14: Typical demand distortion along a supply chain (Screenshot – Copyright Inneon Technologies)

26

The following section details activity

approaches to improve forecast accuracy. It is

recommended that the two metrics mentioned

above be used to measure the success of the

activities.

2.3.4 Guideline for measuring and

increasing forecast accuracy

Insufcient reconciliation of synchronously

running planning systems within a company

and its departments can result in coordina-

tion problems. Sharing information, enforcing

decisions and generally improving collabora-

tion is therefore essential in this context. It is

recommended that a standard framework be

created, e. g. by using the same metrics in all

planning processes and exchanging demand

data via standardised electronics formats.

Introducing a global Sales & Operations Plan-

ning process (S&OP) can help counteract the

lack of focus and system reconciliation. This

process ensures that the operational plans

are coordinated between all functions of an

organisation and thus support the business

plan in the long term.

A clear differentiation between original and

adjusted forecast data must be provided to

ensure that the analysis of deviations is not

neglected but continues to be pursued. Coher-

ent and, above all, current data is required for

a good forecast. It is recommended that the

data at the point of sale be used to capture

demand changes more quickly and more accu-

rately. This data updated on a daily or weekly

basis reects the actual and direct customer

demand. Standardised formats, preferably

the Electronic Data Exchange (EDI), should be

used for sharing this information along the

entire supply chain.

The systematic evaluation of the forecast

and analysis of its origins is one of the basic

requirements for a company’s planning pro-

cess. Systematic reporting using MAPE or

SMAPE for metrics supports the identication

of sources of error and misinterpretations.

2.3.5 Guideline for measuring and

reducing the bullwhip effect

The following discusses recommendations for

actions to counteract the operational causes

(demand signal processing, rationing and

shortage gaming, order batching and price

uctuations) of the bullwhip effect.

Insufcient or delayed information ow along

the supply chain amplies the bullwhip effect.

Improving demand signal processing involves

raising awareness of this effect, providing

good forecasts and creating transparency. By

training the parties involved in the supply

chains, the presence and causes of the bull-

whip effect can be communicated. Accurate

forecasts can also help reduce distortion of

the original demand along the supply chain.

Measures to improve the forecast accuracy

are detailed in chapter 2.3.4 Guideline for

measuring and increasing forecast accuracy.

However, it is not sufcient that each com-

pany improves its in-house forecasts for its

own use. For a reliable forecast (not limited

by production capacities), it is necessary to

have access to demand forecasts of supply

chain participants. In order to be able to make

reliable statements (capacity or order unitre-

lated) in terms of the forecast and delivery

MAPE

=

1

n

Ʃ

At – Ft

At

n

t = 1

SMAPE

=

Ʃ

At – Ft

Ʃ

n

t

=

1

n

t

=

1

( At – Ft )

t period 1 to n

n number of periods for which MAPE or

SMAPE is calculated

F

t

forecast for period t

A

t

actual demand in period t

27

time, companies need information on inven-

tories, production capacities, cycle times and

expected coverage rate of the inventory cur-

rently processed in addition to the forecasts.

Exchanging this data provides transparency,

thus ensuring long-term improvement of

the information ow along the supply chain

and counteracting one cause of the bullwhip

effect.

Rationing and shortage gaming is another

cause of the bullwhip effect. In this context

it can be helpful to segment the customers.

Instead of allocating the limited supply of

goods according to the actual order volume

on hand, customer prioritisation should follow

other criteria such as customer-specic plan-

ning quality and the general availability of

forecast data for a dened time frame beyond

the mere replenishment time.

Order batching also contributes to demand

distortion. Customers can break bulk orders

by ordering minimum quantities only instead

of their actual demand, for instance. While

higher costs may arise from the adjustment of

the customer’s production to the lower order

quantities, truckloads containing different

products from the same manufacturer may

help reduce xed transportation cost for the

individual orders. The external logistics ser-

vice provider may group different orders, also

from other companies, and thus lower freight

charges considerably. This approach can be

implemented company-wide provided that the

order volume is sufciently high.

Frequently changing prices result in a sim-

ilar phenomenon to order batching. Lower

sales prices induce customers to buy more

products than they actually need. However,

this may annoy customers who purchased the

same products earlier at regular sales prices. A

low-price policy can help counteract these two

effects of price uctuations by guaranteeing

customers permanently low sales prices.

These recommendations clearly show that it

is only possible to limit the bullwhip effect

by a mutual exchange of information, i. e.

mutual trust and transparency within the sup-

ply chain.

2.4 Meaning of a robust supply chain

Companies face major challenges resulting

from growing market globalisation and hence

continuously increasing complexity, which

requires companies to permanently optimise

their internal value chain and supply. Not only

must companies respond to higher prices and

changing market competition, they also must

manage a greater number of variants and

reduce delivery times and inventories.

17

Companies that fail to adapt in time to the

changing conditions will face substantial dis-

advantages in terms of protability and long-

term competitiveness.

18

17 Becker, 2007

18 Beckmann, 2004

Figure 15: It is essential that supply chains are robust. (Copyright ZVEI)

Sou rce Make Deliver

Design

Pla n

28

However, it is not enough just to meet and fur-

ther optimise the new requirements caused by

market changes. In closely linked global supply

chains, minor network interruptions may result

in breakdowns along the entire supply chain.

19

Therefor the focus of supply chain management

should also be on end-to-end planning, con-

trolling and monitoring processes along entire

value adding networks (supply chains)

20

, with

the aim is to identify weaknesses and risks in

supply chains early on and implement robust

processes to prevent breakdown.

2.5 Denitionofarobustsupplychain

No clear term denition of robust supply chain

can be found in the literature. Robust processes

are described as insusceptible to external errors.

Another denition of robust processes refers to

their ability to eliminate minor process devia-

tions autonomously.

21

This means that a robust supply chain must be

as reliable and immune as possible to exter-

nal inuences and risks, possibly intercept-

ing errors when they occur to minimise their

impact on downstream processes.

19 Dumke, 2013

20 Beckmann, 2004

21 Becker, 2005

2.6 Development of a robust supply

chain

To design a supply chain as robustly as possi-

ble and hence protect it from potential risks, it

is necessary to identify the weaknesses of the

individual areas of a supply chain (e. g. pur-

chasing, materials management and inbound

logistics, production planning and production,

requirements and sales planning, development

and design, outbound logistics and warehous-

ing). This paper rst discusses the risks that

may occur in the individual areas. Then, the

protection measures identied for these areas

in order to improve the robustness of the sup-

ply chain ar detailed.

2.6.1 Risks to the individual areas

A supply chain risk is the damage – assessed

by its probability of occurrence – that affects

more than one company in the supply chain

and that is caused by an event within a com-

pany, within a supply chain or its environ-

ment.

22

A number of international and rec-

ognised standards (e. g. ISO 31000 – Risk

Management, IEC 31010 – Risk Manage-

ment – Risk Assessment Techniques).

Comprehensive risk management requires

knowledge of the risks that may occur in the

different areas of the supply chain.

23

A classication of supply chain risks according

to the SCOR

®

areas is provided in the following

subsections. The Design area has been added

since, in our opinion, it also poses substantial

risks for supply chains. The Return process is

not considered since we feel it plays a minor

role in this context.

22 Kersten, Hohrath and Winter, 2008

23 Lasch and Janker, 2007

Figure 16: Research and development areas signicantly inuence the complexity

of the future supply chain. (Copyright Escha)

29

2.6.1.1 Design

The future complexity of the supply chain

and its structures is already being deter-

mined in the eld of research and develop-

ment (Design). In addition to procurement

costs, production and distribution, the prod-

uct architecture greatly inuences the variant

diversity.

24

Greater variant diversity means higher com-

plexity and risks in the downstream supply

chain processes. The use of extremely specic

purchased parts and technological dependen-

cies on individual suppliers can lead to supply

chains that are difcult to control and which

face higher risk of disruption. In this way, the

design process directly inuences the pur-

chasing strategy and supply chain of a com-

pany and dictates process ows.

Possible supply chain risks in the area of

Design are:

• increased complexity caused by variant

diversity,

• technological dependencies, specic pur-

chased parts,

• single sourcing,

24 Corsten and Gabriel, 2004

• unforeseeable procurement costs,

• geographical risks caused by the necessity

to procure goods from volatile markets,

• long-term availability of purchased parts,

• absent/insufcient collaboration with down-

stream supply chain areas (comparing/shar-

ing specialist knowledge).

2.6.1.2 Plan

Possible risks for the Plan process may arise

from the ow of information and material ow

control and planning. The uncertainties and

risks occurring here may impact all processes.

Inaccurate planning is often the result of inac-

curate information (see chapter 2.3). If infor-

mation about changing requirements or fore-

casts, capacity shortages, process disruptions

or imminent or existing supply bottlenecks

is not passed on or passed on too late within

company, the Plan process provides no basis for

decision-making. Risk indicators are thus either

incorrect or incomplete or not identied at all.

Supply

Planning

Capacity

Planning

Demand

Planning

Production

Management

Order

Management

Scenario

Plan

Marketing-

Demand

Sales

Plan

Supply Plan Demand Plan

Figure 17: During the planning process it is essential to consider foreseeable and unforeseeable events to be able to respond directly.

(Copyright Inneon Technologies)