In Search of Control

Denmark Country Report

Shifting the paradigm,

from opt-out to all out?

Myrthe Wijnkoop

Anouk Pronk

Robin Neumann

Shifting the paradigm,

fromopt-out to all out?

Myrthe Wijnkoop

Anouk Pronk

Robin Neumann

Clingendael Report

February 2024

February 2024

© Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’.

Cover photo © Reuters

Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user

download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of

International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use,

the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material

oron any copies of this material.

Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed,

distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael

Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be

obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]).

The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark

and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or

metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL.

About the Clingendael Institute

The Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ is a leading think tank and academy

on international affairs. Through our analyses, training and public platform activities weaim to inspire

and equip governments, businesses, and civil society to contribute to asecure, sustainable and just

world.

The Clingendael Institute

P.O. Box 93080

2509 AB The Hague

The Netherlands

Follow us on social media

@clingendaelorg

The Clingendael Institute

The Clingendael Institute

clingendael_institute

Clingendael Institute

Email: info@clingendael.org

Website: www.clingendael.org

About the authors

Myrthe Wijnkoop is a senior research fellow at Clingendael’s EU & Global Affairs

Unit and a cum laude graduate in public international law and Dutch law. Her areas

of expertise include international, European, and national refugee and asylum law,

and the politics of asylum and migration in an EU and European context. Myrthe has

more than twenty years of legal and political-strategic experience in the asylum

domain from the perspective of politics, governance, civil society, international

organisations as well as (policy) research. She is currently project leader of the

Ukraine migration and return study and has been involved as a migration advisor in

the StateCommission on Demographic Developments 2050.

Anouk Pronk is a Junior Research Fellow at the EU & Global Affairs Unit of the

Clingendael Institute, whose work focuses on international asylum and migration

policies and their impact in both the EU and the Netherlands. She holds an MA in

Peace and Conflict Studies from University College Dublin (First Class Honours),

an LLB in Dutch Law, including European Migration and Asylum Law, and a BSc in

International Relations and Organisations, both from Leiden University.

Robin Neumann is an intern at the Clingendael Institute for the EU & Global Affairs

unit, conducting research on migration policies and asylum systems. She is pursuing

an MSc in International Relations & Diplomacy at Leiden University, and graduated

magna cum laude in her Global Studies BA focusing on peace and conflict from

the University of California, Berkeley. Prior to Clingendael she was an intern at the

International Organization for Migration in Copenhagen, Denmark working for the

Labour Migration and Climate Migration teams.

About the Project

In December 2022, the Dutch government initiated a working group focussing on

the‘fundamental reorientation of the current asylum policy and design of the asylum

system.’ Its aim is to further structure the asylum migration process, to prevent and/

or limit irregular arrivals, and to strengthen public support for migration. One of the

assumptions is that the externalisation of the asylum procedure could be a feasible

policy option through effective procedural cooperation, with a country outside the EU,

that ‘passes the legal test’. In other words, if it would be operationalized in conformity

with (international) legal standards and human rights obligations. In that context, the

working group expressed the need for more insight on how governments with other

legal frameworks than the Netherlands, as an EU Member State, deal with the issue

of access to asylum, either territorial or extra-territorial, in order to provide thoughts

orangles for evidence-based policy choices by the Dutch government, at national

and/or European level.

The purpose of this comparative research project, led by the Clingendael Institute,

was to collect existing knowledge about the asylum systems of Australia, Canada,

Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United States, and to complement this with an

analysis of national legislation, policy, and implementation practices, focussing on

access to (extra-)territorial asylum. While there are overlaps, each of the asylum

and refugee protection systems in the research project operates in very different

geographical situations and political contexts.

Beyond the five country case studies, a separate synthesis report that is based on a

comparative analysis of the respective legal frameworks and the asylum systems of

those countries addresses directions for Dutch courses of action. The synthesis report

and the country case studies can be accessed here.

The main question to be answered in the national reports is: Which instruments

are applied or proposed by Australia, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands and the

UnitedStates concerning or affecting access to asylum procedures and humanitarian

protection

Therefore, the country research focuses on several central elements of the national

asylum systems, including their access to, and implementation of, interdiction

practices, border and asylum procedures and other legal pathways. These were put

in a broader public, political and legal context, taking into account the countries’

national policy aims and objectives.

Contents

Introduction

Setting the scene: generalbackground and relevant developments

International legal framework

Border management in policyand practice

Access and national asylumprocedures

Extraterritorial access toasylum

Return in the context of migration cooperation

Statistics

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

1

Introduction

When assessing the topic of access to (extra)territorial asylum in a European

context, Denmark holds a certain ‘status aparte’. Denmark joined the EU in 1973

after cautious consideration, having a carefully balanced approach towards

European integration. The country’s position can be characterized by a ‘soft’

form of Euroscepticism, making the decision to ‘opt in’ when there are considered

benefits.

1

Denmark is not part of the eurozone and negotiated several other

‘opt-outs’ among which the (larger part of the) common EU rules on asylum and

migration. This means that they are formally not bound by the EU asylum acquis,

which provides them with a unique position as EU-Member State.

After 2015 when 1,2 million people, mostly from Syria, were seeking refuge in the

European Union, the Danish government, with broad consensus in parliament,

has implemented legislation and policies to further restrict asylum protection.

2

Primary aim was, and still is, to make Denmark less attractive to asylum seekers.

Residence permits are now granted on a temporary basis with a view to returning

refugees to their countries of origin as soon as possible, and not to integration

and long-term residence: a self-indicated so-called ‘paradigm shift.’

3

Moreover,

the Danish government is very straightforward, and even takes ‘pride’ in

communicating their message of pursuing a very strict (territorial) asylum policy.

4

The explicitly stated and openly communicated target of the Danish government

is furthermore to prevent asylum seekers from arriving ‘spontaneously’ at the

territorial borders of Denmark: ‘zero people should apply for asylum in the

1 Aarhus University, “An overview of Denmark and its integration with Europe, 1940s to the

Maastricht Treaty in 1993,” Nordics Info, accessed on 12 October 2023.

2 The restriction of rights of asylum seekers started already in 2002, when the government under

Anders Fogh Rasmussen removed de facto status (with the aim to explicitly not provide protection

for Somalis), ended embassy asylum, changed the Refugee Appeals Board members etc.

SeeAarhus University, “Danish immigration policy, 1970-1992,” Nordics Info.

3 The Danish Institute for Human Rights, You can never feel safe: an analysis of the due process

challenges facing refugees whose residence permits have been revoked, 2022; See also

JensVedsted-Hansen, Stinne Østergaard and others, Paradigmeskiftets konsekvenser. Flygtninge,

stat og civilsamfund, August 2023; Jens Vedsted-Hansen, Refugees as future Returnees. Anatomy

of the paradigm shift towards temporary protection in Denmark, CMI 2022-6.

4 See also Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen, “Refugee policy as ‘negative nation branding’: the case of

Denmark and the Nordics”, in: Danish Foreign Policy Yearbook 2017.

2

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

country’.

5

Of particular interest in this context is the 2021 amendment to the

Danish Aliens Act. This amendment provides for the possibility to transfer

asylum seekers to a third state outside the EU for processing the asylum claim,

protection in that state or return from there to the country of origin (section29).

6

This legislation fits in a long Danish tradition of focussing on the external

dimension of European asylum and migration policies, including being at the

forefront of the European debate on externalizing asylum procedures to countries

outside the EU. Already in the 1980’s Denmark put forward a plan for external

processing of asylum claims during a meeting in the UN General Assembly.

7

A factor that frequently surfaces in political and public debates on migration in

other EU Member States, such as the Netherlands, is that Denmark can pursue

these policy lines because of the EU asylum opt-out. And that an opt-out of the

EU acquis would thus be the panacea to manage asylum better.

8

However, the

fact that Denmark is indeed bound to several (other) international and European

legal obligations when applying these national laws and policies in practice is

often overlooked.

In this report we will look at Denmark’s asylum policies and protection system,

describing and analysing amongst others the applicable legal framework, the

implementation of border and asylum procedures, return policies and relevant

statistics. The report will also discuss in more detail any form of extraterritorial

access to asylum, through legal pathways and other policies, as well as migration

cooperation/partnerships with third countries in as far as they concern access to

protection. To which extent are the aims of the Danish government reached, and

at what costs? Are there lessons to be learned for the Netherlands (and other EU

Member States), considering the opt-out position that Denmark currently holds?

To what extent does the Danish ‘status aparte’ play a significant role in building

both the policy directions and the narrative itself?

5 Ritzau, “Mette Frederiksen: The Goal is zero asylum seekers to Denmark,” Nyheder, 22 January

2021.

6 See for a comprehensive legal assessment of this legislation: Nikolas Feith Tan and Jens

Vedsted-Hansen, “Denmark’s Legislation on Extraterritorial Asylum in Light of International and

EU Law,” 15 November 2021; Nikolas Feith Tan, “Visions of the Realistic? Denmark’s legal basis

for extraterritorial asylum,” Nordic Journal of International Law 91, 2022, p. 172-181; See also

Chantal Da Silva, “Denmark passes a law to send its asylum seekers outside of Europe,” Euronews,

3June2021.

7 Dutch Advisory Council on Migration (ACVZ), “External processing,” December 2010, p. 15.

8 Parliamentary documents, Kamerstukken II, 35 925, nr. 43, 23 September 2021.

3

1 Setting the scene:

generalbackground and

relevant developments

Political and sociocultural context: paradigm shift and a ‘broad

national consensus’

The fact that Denmark opted out of the EU asylum acquis does not implicate that

Denmark is a self-centred state. The driving force behind Denmark’s accession

to the EEC was the desire to become part of an open European economy, rather

than support for federalism.

9

The Danish government is an active member of

the European and international community and has for example a long tradition

as a humanitarian actor in multilateral relations and international cooperation.

Denmark is high ranking in lists of humanitarian donor countries and, at least

formally, sets the standard of Official Development Assistance (ODA) at the

UNgoal of 0,7% GNI.

10

At the same time, Denmark remains very keen to retain its national sovereignty

in certain policy domains. It has installed multiple institutional safeguards to

allow for selective participation in European integration, such as safeguards in its

Constitution with respect to delegating power, and a parliamentary committee

which has oversight over decisions in Europe. Sincethe2022 invasion of Russia in

Ukraine, Denmark however moved a bit closer to the EU again.

Denmark has thus adopted a rather pragmatic non-federalist approach

towards the EU and certain policy domains such as asylum and migration.

Keyparliamentary decisions on European integration and related topics are

made by consensus between the main political parties, regardless of the

coalition in power.

11

The national political debate on asylum and migration in

Denmark has in recent years become no longer a topic with a traditional left-

9 Aarhus University, “An overview of Denmark and its integration with Europe,” 25 February 2020.

10 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, The Government’s priorities for Danish development

cooperation 2023-2026, April 2023; However, in practice the government is falling short:

Concord,AidWatch, Bursting the ODA Inflation bubble, 2023.

11 Aarhus University, “An overview of Denmark and its integration with Europe,” 25 February 2020.

4

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

right political divide. Rather, parties such as the Social Democrats have begun to

support stricter asylum policies and limited the access to permanent protection

in the country. This has been done by addressing the discussion of cost and

benefits of migration from the perspective of the national community, resulting

in policies as regards territorial access to asylum that are close to those of

right-wing parties such as the Danish People Party, and a national consensus

on the topic of migration. Thus, a broad majority in the Danish parliament

supports restrictive migration and asylum policies and strict rules for access and

settlement of persons originating from outside the EU/EEAS.

12

The general focus

shifted from integration to return, from permanent residence to revocation of

protection: the ‘paradigm shift’.

13

A clear manifestation of this paradigm shift is that since 2015 a set of restrictive

legislative and policy changes was passed by the Danish parliament.

14

A new

temporary subsidiary protection ground was introduced in the Aliens Acts

(section 7(3)) applicable to situations of generalized violence, whereby the right

to family reunification is withheld for initially the first three (and currently two)

years of residence.

15

This protection ground is mostly used for Syrians as they are

the largest group to receive temporary subsidiary protection. Also, the threshold

for revocation of asylum protection other than Convention refugee status was

lowered: a durable improvement of the security and human rights situation in the

country of origin is no longer necessary.

16

This strong focus on the revocation of

asylum residence permits is rather unique in comparison to other EU Member

States, as the criteria for cessation in EU acquis require a high(er) standard.

17

Other changes to the Danish asylum legislation dealt with the confiscation of

12 Nikola Nedeljkovic Gøttsche, “Folketingets partier er stort set enige om Danmarks

udlændingepolitik,” Information, 14 July 2018.

13 L 140, amendments to the Danish Aliens Act. See also Emil Søndergård Ingvorsen,

“‘Paradigmeskiftet’ vedtaget i Folketinget: Her er stramningerne på udlændingeområdet,”

DRPolitik, 21 February 2019.

14 L 87, amendments to the Danish Aliens Act.

15 The original legislation spoke about three years ‘waiting time’ for family reunification, except for

exceptional circumstances. However, in M.A. v. Denmark (9 July 2021) the European Court on

Human Rights (ECtHR) stated that this provision did not entail a reasonable balance of interests

and was therefore in violation of article 8 of the Convention. The duration was then changed to

twoyears.

16 See more extensively on these matter under ‘national asylum procedure’.

17 Nikolas Feith Tan, “The End of Protection the Danish paradigm shift and the law of cessation,”

Nordic Journal of International Law, 90, 2021, p. 60-85.

5

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

assets from asylum seekers (the widely commented so-called ‘jewelry-law’),

18

introduction of short-term residence permits, mandatory review of protection

needs, further restrictions on family reunification, reduced socials benefits for

refugees and restrictive criteria for permanent residency. This set of legislative

and policy changes called for quite some criticism from refugee law experts

andUNHCR.

19

While lowering protection standards and limiting the territorial protection space,

Denmark put much effort in the external dimension of asylum and migration

policies. Both through migration cooperation with third countries, as for example

the MoU with Rwanda, as well as a focus on exploring the possibilities of

outsourcing and/or externalizing asylum procedures to countries outside the

EU. This complies with a long tradition of Danish policy thinking. Already in 1986

Denmark put forward in a UN setting the idea of externalizing asylum procedures.

The Danish government was one of the EU Member States supporting the 2003

United Kingdom proposal to amend EU asylum policy, stating that persons

seeking asylum in EU Member States should be automatically sent to a transit

and processing center outside the EU, where their applications would then be

assessed.

20

And again Denmark together with the UK and the Netherlands were

frontrunner EU Member States in promoting and pushing forward initiatives

to strengthen refugee protection in the region such as multilateral initiatives

like the Syria Refugee Response and Resilience Plan (3RP) and the Ethiopia

Country Refugee Response Plan (ECRRP). Denmark is also one of the driving

actors behind the concept of EU Regional Protection Programmes,

21

and had a

leading role in the programme in Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq (RDPPII 2018-2021).

18 The Danish Parliament, “L 87 Forslag til lov om ændring af udlændingeloven,” 10 December 2015;

See also Harriet Agerholm, “Denmark uses controversial ‘jewellery law’ to seize assets from

refugees for first time,” The Independent, 1 July 2016; The Local, “Here’s how Denmark’s famed

‘jewellery law’ works,” 5 February 2016; Ulla Iben Jensen and Jens Vedsted-Hansen, “The Danish

‘Jewellery Law’: When the signal hits the fan?”, EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy,

4March 2016.

19 UNHCR Northern Europe, “Recommendations to Denmark on strengthening refugee protection,”

11 January 2021; UNHCR Nordic and Baltic States, “Observations from UNHCR on the Danish law

proposal on externalization,” March 2021.

20 UK Home Office, “New International Approaches to Asylum Processing and Protection,”

March2003.

21 Thea Hilhorst et al., “Factsheet Opvang in de regio: een vergelijkende studie,” 18 January 2021;

ECRE, “EU External Cooperation and Global Responsibility Sharing: Towards an EU Agenda for

Refugee Protection”, February 2017.

6

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

Denmarkalso has one of the oldest refugee resettlement schemes in cooperation

with UNHCR in Europe.

22

This fits the Danish profile of a humanitarian actor, with

a focus on foreign relations and development cooperation, seeking multilateral

approaches to tackle asylum and migration issues.

23

Also NGO’s such as the

Danish Refugee Council have large scale humanitarian programmes in regions

oforigin and transit.

24

Asylum and migration nexus: economic context

Most immigrants to Denmark are however not asylum seekers, but come

from other European countries, reaching almost 75,000 people in 2021.

25

Furthermore,approximately 12,000 migrant workers and around 9,000 foreign

students received residence permits that year. With some of 2000 asylum

applications in 2021, this constitutes the smallest group of immigrants to

Denmark.

26

In recent years, due to an ageing population, Denmark has been experiencing

labour shortages, specifically skilled work, with 42% of Danish companies

reporting that they face challenges filling positions in the first quarter of 2022.

27

With the Danish unemployment rate being quite low, 2.5% in August 2023,

28

Denmark has to look elsewhere to fill in the labour shortages. In March 2023,

amendments to the current Danish Aliens Act were adopted to strengthen

22 The numbers of refugees which are indeed resettled in practice are significantly decreasing,

and the resettlement status itself is no longer permanent. See under ‘Extraterritorial asylum:

legalpathways’.

23 UNHCR, “Denmark.” See also the 2022 governmental agreement with references to the multilateral

approaches om migration (p. 39-40).

24 The Danish Refugee Council (DRC) is an NGO which also has specific designated tasks in the

Danish asylum procedure, for example on legal assistance and the manifestly unfounded cases

(see further under national asylum procedures). DRC Asylum also takes part in resettlement

missions and sometimes fact-finding missions. DRC Asylum’s role in the Danish procedure is not

linked to the international work of DRC. See website Danish Refugee Council.

25 Einar H. H. Dyvik, “Number of residence permits granted in Denmark in 2022, by reason,” Statista,

8June 2023.

26 Einar H. H. Dyvik, “Number of residence permits granted in Denmark in 2022, by reason,” Statista,

8June 2023.

27 European Commission, “Labour Market information: Denmark,” 17 January 2023.

28 Trading Economics, “Denmark Net Unemployment Rate.”

7

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

international recruitment of talented third-country nationals.

29

One of the

changes allows companies to apply to the certification of the Fast track scheme,

through which foreign skilled workers can be brought to Denmark through

quicker procedures.

30

In a push to support the unionization of staff, these

companies must be covered by a union association agreement. The extension of

the acceptance ‘positive list’ for skilled work and those with higher education is

another amendment, which specifically lists professions experiencing a shortage

of qualified labour.

31

Lastly, a supplementary pay limit scheme was created,

which requires a labour migrant to have a job offer with a minimum annual salary

of DKK 375,000 (equivalent to approx. 50,200 EUR).

32

Last year, an increase of the employment rate of non-Western immigrants was

measured until 55.8%, an all-time high for Denmark.

33

While the importance of

access to the labour market and gaining employment have been recognized as

key elements of integration, the recent ‘paradigm shift’ has shifted Denmark’s

focus away from integration measures.

34

Currently, the asylum systems and

labour migration framework are distinct domains in legislation, separated

between ‘asylum’ and ‘work’. The law states that an asylum seeker who has

a pending case with immigration services and is residing in the country for

at least 6 months, can apply to the DIS for approval to work for a year in the

meantime.

35

This excludes asylum seekers in the Dublin procedure.

36

A contract

29 See for example on nurses from Iran: Rasmus Dyrberg Hansen, Jonas Guldberg, and

AnnetteJespersen, “Vejle Kommune hyrer sygeplejersker fra Iran, mens de søger godkendelse til

job i Danmark,” DR, 15 September 2023.

30 Shkurta Januzi, “Denmark Amends Its Aliens Act in a Bid to Lure More Foreign Workers & Students,”

Schengen Visa, 28 March 2023.

31 The Danish Immigration Service, “The Positive Lists.”

32 See amongst others: Mads Hørkilde, “S-minister siger nej til at åbne for »ladeporte« for

udenlandsk arbejdskraft,” Politiken, 17 September 2023; Jyllands-Posten, “Minister afviser at

lempe regler for international rekruttering,” 18 September 2023; DR, “Løkke: Virksomheder med

overenskomst skal kunne få alle de udlændinge, de vil | Politik,” 29 August 2023; Dansk Erhverv,

“Dansk Erhverv: Vi skal have et paradigmeskifte for udenlandsk arbejdskraft,” 5 September 2023;

Berlingske, “Løkke & co. med usædvanligt forslag: Vil uddanne og hente sygeplejersker og sosu'er

fra Filippinerne,” 6 July 2023.

33 European Commission, “Denmark: Employment level of migrants and refugees reaches record

high,” 7 January 2022.

34 Refugees Denmark, “Refugees are absolutely necessary for the Danish labour market,”

3November 2019.

35 The Danish Immigration Service, “Conditions for Asylum Seekers.”

36 Interview with DRC d.d. 2 November 2023.

8

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

must be entered with the DIS which lays out certain conditions which must be

met. However, in practice, most asylum seekers do not work due to the difficulty

in obtaining work (and thus subsequent authorization) while they are placed in

one of the accommodation centers. Different rules apply however for displaced

Ukrainians, who are allowed to work directly under the national temporary

protection scheme.

37

37 More about rights for Ukrainians can be found here: DRC, “Ukraine: FAQ.”

9

2 International legal

framework

Convention obligations

38

Denmark has ratified the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of

Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, as well as the other relevant UN human rights

treaties such as Convention against Torture (CAT), International Convention on

Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Convention on the Rights of the Children

(CRC). Denmark is also party to the European Convention of Human Rights

(ECHR) and is bound by the European Fundamental Rights Charter (article 18

and19) as source of primary EU law. The legal protection obligations deriving

from these treaties, with non-refoulement as a cornerstone principle, are

implemented in the national legislation, more in particular, article 7 of the

DanishAliens Act. The ‘convention status’ or ‘K-status’ (art. 7(1)) refers directly

to the UN Refugee Convention. Subsidiary protection (B-status or de facto-

status) is granted if a person risks treatment in violation of article 3 ECHR upon

return to the country of origin, including individuals who run a real risk because

of meremembership of a group.

39

The third protection ground derives from

European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) jurisprudence which is subsequently

integrated in Union law, and deals with general temporary protection status

forreasons of indiscriminate violence and attacks on civilians in the country of

origin (non-individualized violence).

40

In general terms, the scope of the protection against refoulement in the ECHR,

as interpreted by the ECtHR, is broader than under the Geneva Convention.

41

Any return of an individual who would face a real risk of being subjected to

treatment contrary to these articles is prohibited. Moreover, protection against

the treatment prohibited by Art. 3 ECHR has been considered more absolute

38 This paragraph equals for a large (generic) part the paragraph on convention obligations in

theDutch country report, as this part of the legal framework applies to both countries.

39 ECtHR, Salah Sheekh v. The Netherlands, 1948/04, 11 January 2007.

40 ECtHR, NA v UK, No. 25904/07, 17 July 2008.

41 Vladimir Simoñák and Harald Christian Scheu, Back to Geneva. Reinterpreting Asylum in the EU.

Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, October 2021, p. 20.

10

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

in several Court rulings.

42

To prevent refoulement, it is not per se required to

admit a person to the territory of a state, if sending him or her back does not

lead to a situation where the person would be persecuted or runs a real risk of

torture, inhumane or degrading treatment.

43

However, without assessing the

individual case, it would be rather difficult to know whether someone has an

arguable claim of a real risk of refoulement. So, ensuring effective access to an

asylum procedure is a precondition to ensure the principle of non-refoulement.

44

In addition, article 4 of Protocol No. 4 to the ECHR prohibits collective

expulsion. This prohibition also requires that there is a reasonable and objective

examination of the specific case of each individual asylum seeker.

45

If a country has jurisdiction, there is an obligation to respect and guarantee the

human rights enshrined in the applicable international legislation. If Denmark,

as State-party to the ECHR, violates those obligations,

46

the state can be held

accountable for an ‘internationally wrongful act’ by the ones whose rights have

been violated.

47

In the context of the ECHR jurisdiction this is not only territorial,

48

but also applied extra-territorially if there is effective (territorial, personal or

42 Chahal v. United Kingdom, ECtHR judgment of 15 November 1996, paras. 76 and 79, referring

to Soering v. United Kingdom, ECtHR judgment of 7 July 1989, para. 88, Ahmed v. Austria,

ECtHRjudgment of 17 December 1996, Ramzy v. Netherlands, ECtHR judgment of 27 May 2007,

para. 100, Saadi v. Italy, ECtHR judgment of 28 February 2008, para. 137. See Jens Vedsted-

Hansen: European non-refoulement revisited, in: Scandinavian Studies in Law, 1999-2015, 272.

43 Daniel Thym, “Muddy Waters: A guide to the legal questions surrounding ‘pushbacks’ at the

external borders at sea and at land,” EU Migration Law Blog, 6 July 2021.

44 See on this subject matter also Monika Sie Dhian Ho and Myrthe Wijnkoop, “Instrumentalization of

Migration,” Clingendael Institute, December 2022.

45 ECtHR, Hirsi Jamaa v. Italy, no. 27765/09, 23 February 2012. See also the Rule 39 measures issued

by the ECtHR in August and September 2021 in order to stop the expedited (collective) expulsions

of Iraqi’s and Afghans stuck at the Latvian, Lithuanian and Polish borders (ECtHR Press Releases of

21 August 2021 and 8 September 2021).

46 ECtHR, M.A. v. France, No. 9373/15, 1 February 2018; ECtHR, Salah Sheekh v. the Netherlands,

No.194/04, 11 January 2007, para. 135; ECtHR, Soering v. the United Kingdom, No. 14038/88,

7July 1989; ECtHR, Vilvarajah and Others v. the United Kingdom, Nos. 13163/87, 13164/87,

13165/87, 13447/87 and 13448/87, 30 October 1991. See European Union Agency for Fundamental

Rights, “Fundamental rights of refugees, asylum applicants and migrants at the European

borders,” March 2020, p. 6.

47 International Law Commission, “Draft Articles on State Responsibility, Official Records of the

General Assembly,” Fifth-sixth Session (A/56/10), article 2.

48 EHRM, Soering. v. United Kingdom. No 14/038/88, 7 July 1989 EHRM, Bankovic a.o. v. Belgium a.o.,

No. 52207/99, 21 December 2001; Hoge Raad, IS women v. the Government of the Netherlands,

26June 2020, ECLI:NL:HR:20201148, paras. 4.16-4.18.

11

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

functional) control over another territory or over individuals who have carried out

the act or omission on that territory.

49

For example in the Hirsi v. Italy case, the

ECtHR found that a group of migrants who left Libya with the aim of reaching

the Italian coast, and that were intercepted by ships from the Italian Revenue

Police and the Coastguard and returned to Libya, were within the jurisdiction of

Italy. According to the ECtHR a vessel sailing on the high seas is subject to the

‘exclusive jurisdiction of the state of the flag it is flying’.

50

This means that Denmark cannot exempt itself from its human rights obligations,

including non-refoulement and access to asylum, by declaring border areas

as non-territory or transit zones or to externalize asylum procedure to other

countries: the determining factor remains whether or not there is jurisdiction,

either/and through de jure or de facto control by the authorities.

51

This does

however not mean that access to asylum can only be provided for on Danish

territory. The 1951 Refugee Convention states that refugees must be protected,

but does not in itself prohibit states negotiating cooperation agreements on

where that protection is guaranteed, as long as the preconditions fulfill the

legal state obligations. Furthermore, the ECtHR has in 2020 drawn a line with

regards to gaining territorial access to the European Union. In its judgment in the

case of N.D. and N.T. v. Spain it concluded that Spain did not breach the ECHR

in returning migrants to Morocco who had attempted to cross the fences of

the Melilla enclave. The Court reasoned that because the group had not made

use of the entry procedures available at the official border posts, the lack of an

individualized procedure for their removal had been a consequence of their own

conduct (i.a. the use of force and being in large numbers).

52

In other words, the

line of argumentation in this case does require states to deploy effective legal

options and means for access to protection for third country nationals, however it

also takes into account the actions of the applicants to that effect.

Denmark, when becoming signatory to the ECHR, also adhered to the

interpretation of those human rights through the jurisprudence of the ECtHR.

Inthe case M.D. and others on Syrian asylum seekers, who were denied asylum

49 See also February 2022. See also Maarten den Heijer, Europe and Extraterritorial Asylum, 2012;

Lisa-Marie Klomp, Border Deaths at Sea under the Right to Life in the European Convention on

Human Rights, 2020; Annick Pijnenburg, At the Frontiers of State Responsibility. Socio-economic

Rights and Cooperation on Migration, May 2021.

50 ECtHR, Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy, No. 27765/09.

51 See also Sergio Carrera, “Walling off Responsibility,” CEPS, nr. 2021(18), November 2021, p. 12.

52 ECtHR, N.D. and N.T. v. Spain, Nos. 8675/15 and 8697/15, 13 February 2020.

12

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

in Russia, the ECtHR found that it would be a violation of ECHR Art. 2 and Art. 3

if Russian authorities returned the asylum seekers to Syria.

53

The Danish Refugee

Appeals Board (RAB) has considered the judgment but did not find that there was

a need to change the current practice regarding Syrian cases: according to the

RAB the case dealt with specific individualized aspects of the claim rather than

the general exceptional nature of the conflict and had therefore no wider impact

than that particular case.

54

EU law: asylum and migration opt-out

Where Denmark is a party to the international and regional human rights

framework and thus bound by the legal obligations enshrined in the conventions,

Denmark has opted out of the common European asylum and immigration

policies (Title V of Part III of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union)

and is therefore not bound by measures adopted pursuant to those policies.

55

The Danish opt-out with respect to asylum is related to the outcome of a

referendum on the Maastricht Treaty in 1992.

56

In this referendum, a majority

of 50.7% of the Danish voters (with a turnout of 83.1%) rejected the Maastricht

Treaty. The solution for the ratification procedure was found through the

introduction of four Danish opt-outs, including no participation in majority voting

in Justice and Home Affairs.

57

This meant that Denmark did not participate in

the harmonization of EU asylum policies. In December 2015, Denmark held a

referendum specifically on the opt-out concerning Justice and Home Affairs.

Thevote was to determine if Denmark would maintain the exemptions in the

original opt-out or replace it with an opt-in model. Denmark voted not to modify

the original opt-out.

58

53 ECtHR, M.D. and others v. Russia, Nos. 71321/17 and 9 others, 14 September 2021.

54 Flygtningenaevnet (RAB), “Drøftelser vedrørende Syrien-praksis på møde i Flygtningenævnets

koordinationsudvalg den 28. oktober 2021.” 29 October 2021.

55 Articles1 and 2 of the Protocol (No. 22) on the position of Denmark, annexed to the Treaty on

European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. See in this respect also

the ECtHR in MA v. Denmark, 9 July 2021, Application number 6697/18.

56 Aarhus University, “An overview of Denmark and its integration with Europe.”

57 These four opt-outs were agreed in December 1992 in the Edinburgh Agreement and confirmed

in a Danish referendum in 1993 which allowed the ratification procedure to proceed. Theother

threeopt-out were: no participation in the euro; no participation in EU defence; and no partici-

pation in European citizenship.

58 Danish Parliament EU Information Centre, “The Danish opt-outs from EU cooperation,” accessed

on 12 October 2023.

13

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

This means that Denmark is still not part of the Common European Asylum

System (CEAS) and not directly bound by EU legislation on asylum, in particular

the Qualification Directive (2011/95/EU), the Procedures Directive 2013/32/EU),

the Reception Directive (2013/33/EU) and the Temporary Protection Directive

(2001/55/EC).

59

The Return Directive however does apply in Denmark due to the

Schengen cooperation. And Denmark decided to join the Dublin system, which

contains criteria for the responsibility of a country for an asylum application, via

a parallel agreement concluded with the EU in 2006.

60

In practice, the Danish

participation in the Dublin system means that Denmark must observe this

system’s fundamental principle of mutual trust.

61

Denmark’s asylum practices

must offer at least similar procedural and reception standards to asylum seekers

transferred to Denmark under the Dublin II regulation.

62

Despite this approximation of asylum standards, the asylum systems of EU

Member States on the one hand and the Danish standards on the other can

differ, not only in theory (because of the opt-out) but also in practice. The impact

thereof became clear in the 2022 Dutch Council of State’s judgment on the

legality of Dublin transfers of Syrians to Denmark. They would risk losing their

asylum status in Denmark due to ceased circumstances, while the Netherlands

under article 15b and 15c of the Qualification Directive had not deemed parts

59 Denmark did for example not apply the Temporary Protection Directive for Ukrainian displaced

persons, but rather enacted a ‘special law’ in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The law was intended to prepare for and accommodate a high number of asylum-seekers arriving

in Denmark within a short time span. It eased the admissibility for asylum claims for Ukrainians

and allowed for an expedited process to seeking and gaining employment within Denmark.

Thedistribution of asylum-seekers was based around placement in areas where the asylum-

seekers had a pre-existing network, or in areas that have higher job opportunities.

It also contained measures to help Ukrainian children integrate into the Danish schooling system,

while also containing provisions to ensure that they could continue to learn Ukrainian.

60 This agreement extends to Denmark the provisions of Council Regulation (EC) No 343/2003

establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for

examining an asylum application lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national,

and Council Regulation (EC) No 2725/2000 concerning the establishment of ‘Eurodac’ for the

comparison of fingerprints for the effective application of the Dublin Convention. See Council of

the European Union, “Council Decision 2006/188/EC,” 21 February 2006.

61 See also EUAA, “Background note Dublin II Appeals and Mutual Trust, Challenges related to mutual

trust concerns raised in appeals within the Dublin III procedure,” 5 April 2023.

62 This is evidenced by a factsheet filled out by the Danish Ministry of Immigration and Integration,

which makes clear that Denmark offers similar procedural guarantees and reception to asylum

seekers who are transferred under the Dublin system.

14

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

of Syria safe and grants subsidiary protection to Syrians. The Dutch Council

of State held that the Syrian applicant had given sufficient evidence that a

transfer to Denmark would expose him to a real risk of indirect refoulement to

Syria.

63

A year later, in a judgment of September 6, 2023 the Dutch Council of

State held that as the national (Dutch) policies to Syria had changed to a more

individual assessment, the applicant could no longer demonstrate an evidently

and fundamentally different level of protection between the Netherlands and

Denmark, and thus there no longer was a risk of indirect refoulement.

64

The above example shows that despite the Danish opt-outs on asylum, Denmark

is still tied to the standards in other EU countries because of its participation

in the Dublin system and its concept of “mutual trust”. These standards must

generally be in compliance with EU asylum legislation and the interpretation of

this by the EU Court of Justice. Indeed, the Dutch Council of State in its judgment

of 6 July 2022 referred to the Court of Justice judgment in the Jawo case

65

as well as judgments of the ECtHR with respect to responsibility allocation

agreements. It concluded that EU law requires courts to scrutinize the level of

protection in general and with respect to specific groups.

EU standards can also bind Denmark in another manner. In MA v. Denmark

theECtHR, while acknowledging Denmark’s opt-out regarding EU immigration

legislation, referred to the EU family Reunification Directive. In this case,

theEU’s legislative framework left a margin of appreciation to Member States.

However,the fact that the ECtHR referred to EU standards is an indication that

the ECHR, to which Denmark is a party, and EU law are increasingly intertwined.

The ECtHR held: ‘At the same time the Court notes that while Denmark was not

bound by the common European asylum and immigration policies set out in the

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, or by any measures adopted

pursuant to those policies (see paragraph 42 above) it is clear that within the

European Union an extensive margin of discretion was left to the Member States

when it came to granting family reunification for persons under subsidiary

protection and introducing waiting periods for family reunification.

66

63 ABRvS, ECLI:NL:RVS:2022:3797, 19 December, 2022; ABRvS, ECLI:NL:RVS:2022:1864, 6 July 2022.

64 ABRvS, ECLI:NL:RVS:2023:3286, 6 september 2023. See also the press release of the Council of

State: “Nederland mag Syrische vreemdelingen weer overdragen aan Denemarken.”

65 EU CoJ, Jawo v. Germany, C163/17, 9 March 2019, paras 87-93.

66 ECtHR, M.A. v. Denmark, No. 6697/18, 9 July 2021, para. 155.

15

3 Border management in

policyand practice

Despite having government coalitions with different political backgrounds during

the past decades, preserving Denmark’s national identity plays a consistent

central role in its migration policy, explaining its strict visa policy and integration

regulations. The arrival and admittance of substantial numbers of immigrants is

seen as a threat to (or destabilization of) the national welfare system and should

thus be prevented.

67

This is why border controls are encouraged and are an

important part of the asylum and migration system.

Schengen and border controls

Since 2001, Denmark has been part of the Schengen agreement, leading to a

division between internal Schengen borders, neighbouring Schengen members

Germany and Sweden, and external Schengen borders, which are the sea and

air borders.

68

Denmark does not have any external Schengen land borders.

TheDanish police is the responsible actor in managing the borders.

With the aim of improving its border management systems of the Schengen

borders, the Danish police started a collaboration with IDEMIA, a multinational

technology company in November 2021. Specific solutions such as self-service

kiosks, automatic border control (e-Gates), and mobile biometric tablets were

implemented.

69

Denmark has introduced temporary border controls at internal Schengen borders

valid until 11

th

November 2023. Such temporary internal Schengen border controls

are valid under the Schengen Borders Code in case of a serious threat, and only

to be applied as a last measure.

70

There are currently twelve other EU-Member

67 Fondation pour l’Innovation Politique (fondapol), Danish immigration policy: a consensual closing

of borders, February 2023.

68 Danish Police, “Border control,” accessed on 17 October 2023.

69 Shkurta Januzi, “Denmark selects IDEMIA to deliver new border control solution for its external

schengen borders,” SchengenVisa, 28 November 2021.

70 Migration and Home Affairs, “Temporary Reintroduction of Border Control,”; Danish Police,

“Bordercontrol.”

16

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

States that have enacted this exception for various reasons. In the case of

Denmark, the reasons for the recently renewed directive for heightened security

are ‘Islamist terrorist threat, organized crime, smuggling, Russian invasion of

Ukraine, and irregular migration along the Central Mediterranean route.’

71

It more

specifically had to do with the Koran burnings in July 2023. The Danish ministry of

Justice stated that the threat necessitated extra controls regarding who enters

the country. Even those flying into the country from another Schengen country

can expect extra controls.

72

Furthermore, Denmark currently has an active border control presence at its

southern border with Germany as a temporary measure. This measure has been

extended multiple times since its introduction in January 2016. Similarly, Denmark

introduced internal border controls at the Swedish border in November 2019 for

the reason of organised crime and terrorism- executed by regular road, rail, and

ferry checks. The country is currently under revision by the European Commission

for the legality of such controls, due to the requirement of exceptionality for

themeasures.

73

Emergency brake measure or ‘Nødbremse’

Moreover, an ‘emergency brake’ measure was introduced in the budget

legislation of 2017

74

which grants the Minister for Integration the power to

reject asylum-seekers arriving at Danish borders, who have previously transited

through another Dublin-country and thus effectively close the border.

75

Preconditionfor the activation thereof is a crisis situation where the Dublin

regulation is still formally in place, but where the Danish government perceives

71 Ibid.

72 Johannes Birkebaek, “Denmark tightens border control after Koran burnings,” Reuters,

4August2023; Crisis 24, “Denmark: Government extends stricter controls at border checks,”

5September 2023.

73 Bleona Restelica, “Denmark Being Investigated for Systematically Prolonging Border Controls

Since 2016,” Schengenvisa, 17 August 2023.

74 Danish Ministry of Finance, “Finanslov for finansåret 2017,” 2017.

75 “The Foreigner and Integration Minister can in Special Circumstances decide that Foreigners,

that claim to fall under section 7 of the Aliens Act can be rejected entry due to prior travel

from a country that is included in the Dublin agreement. The decision in taken for a period

of up to 4 weeks, and can be extended for a period of up to 4 weeks at a time’. Danske Love,

“Udlændingeloven,” § 28, stk. 7.

17

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

that the agreement has ceased to be enforced in practice and that it thus cannot

reasonably be expected to adhere to the Dublin procedures.

76

This would in practice result in a total ban on territorial asylum: to prevent

asylumseekers that arrive at the Danish-German border, which is the main

border crossing for asylum seekers, to access Danish territory. This legislation

is highly controversial within Denmark, as it could also have severe impact

on cross-border relations with neighboring countries.

77

Currently no policy or

operational plan exists that outlines exact steps that the Ministry should take

in order to physically reject asylum seekers crossing the border.

78

At this point it

remains a dead letter.

Detention

The general grounds for immigration-related detention are outlined in Article 35

and 36 in the Danish Aliens Act. Specifically regarding asylum seekers, article36

lays out that “non-citizens may be detained if non-custodial measures are

deemed insufficient to ensure the enforcement of a refusal of entry, expulsion,

transfer, or retransfer of a non-citizen.”

79

Further provisions with respect to

detention with the view of the possibility to expel rejected asylum seekers can

be found in the Danish Return Act (section 14(2)).

80

This framework is being

used for several groups: refugees who have had protection, while their case is

being reassessed for exclusion-grounds; foreign nationals with other grounds of

76 The explanatory memorandum on this legislation highlights that such a situation would appear if

several countries had in tandem begun to cease enforcing the Dublin rules, but does not specify the

minimum bar for the number of countries that would have to stop enforcing the Dublin agreement

in order to allow the Minister to take this measure. Udlændinge- og integrationsministeren (Inger

Støjberg), the Danish Parliament, “Forslag til Lov om ændring af udlændingeloven,” 15 March 2017.

77 Erik Holstein, “Mette Frederiksen har fået europæisk skyts til sin udlændingepolitik - Altinget - Alt

om politik: altinget.dk,” Altinget, 9 May 2023. It could mean that Denmark can no longer return

asylum-seekers that have travelled through other Dublin countries, or who have been apprehended

while traveling into Denmark. This is indeed mentioned in the explanatory memorandum but

is considered a logical consequence of the fact that the emergency measure would only be

introduced if the agreement in itself has ceased to function. See also Louise Halleskov, “Kort om

“asylnødbremsen”, Rule of Law, 2 March 2020.

78 Anders Sønderup ”Hvordan trækker man nødbremsen, og laver en grænse de uønskede ikke kan

krydse? | Nordjyske.dk,” Nordjyske, 4 March 2020.

79 Global Detention Project, Country Report: Immigration Detention in Denmark: Where officials

cheer the deprivation of liberty of ‘rejected asylum seekers, May 2018, p. 7.

80 Ministry of Immigration and Integration, Return Act (in Danish), “Bekendtgørelse af lov om

hjemrejse for udlændinge uden lovligt ophold.”

18

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

residence, who apply for asylum after an expulsion; and for asylum seekers, who

are criminally convicted and expelled before or while their asylum case is being

processed. This also includes those who try to travel to or through Denmark using

false documents, and who are not deemed to be covered by the protection in

theRefugee Convention art. 31(1).

Time served due to convictions takes place in many different detentions and

prison facilities. Asylum-seekers detained under the Aliens Act are placed at

the Ellebaek Immigration Centre or at Nykøbing Falster Holding Center. In

order to comply with the EU Returns Directive, Denmark introduced a time limit

on immigration detention of initially maximum six months. In case of refusal of

cooperation of the detainee, the court can extend this for another 12months.

81

In2018, the average stay lasted 32 days.

82

In Denmark the limitations to

detention under Dublin also apply to Dublin cases. Once in detention, the

detainee receives free legal aid.

83

DIS’s yearly statistical overview does not

include numbers regarding immigration-related detention.

84

The Danish Prison

and Probation Service however does provide these numbers, stating that in 2021

787 detained asylum seekers were imprisoned, of which 90% were men.

85

After a visit to Denmark in 2019, the European Committee for the Prevention of

Torture (CPT) called the Danish migration detention center Ellebaek out for being

“among the worst of its kind in Europe.”

86

The CPT was critically concerned about

the fact that migrants in detention centers were subject to prison-like (material)

conditions and were bound to prison rules. Degrading treatment and incidents

81 This is in line with article 15 of the EU Return Directive.

82 Council of Europe, Report to the Danish Government on the visit to Denmark carried out by the

European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment (CPT), 7 January 2020, p. 53.

83 Interview DRC d.d. 2 November 2023: DRC offers free legal aid and counselling, but detainees are

also provided with legal representation in the form of a lawyer that can represent them in court.

The possibility for detained asylum seekers to talk with DRC while in detention is regulated by the

section 37 d of the Danish Aliens Act.

84 Global Detention Project, Country Report: Immigration Detention in Denmark, May 2018, p. 13.

85 Kriminal Forsorgen, “Kriminalforsorgen statistik 2021,” 2021, p. 16

86 European Council on Refugees and Exile, “Denmark: Council of Europe shocked over conditions on

Danish Detention Centers and Threatens Legal Action,” 16 January 2020.

19

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

of verbal abuse by the custodial staff was furthermore highlighted.

87

The Danish

Government responded that it planned some material renovation projects to its

detention centers, and that it continuously strives to uphold the liberty and rights

of foreign nationals in detention.

88

After having visited Denmark in June2023,

theCommissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe concluded that

while some material conditions had been improved at Ellebaek, prison-like

manner of operations was still of grave concern, including the use of disciplinary

solidarity confinement.

89

Covid-19 caseload

Between March and July 2020, Dublin transfers of asylum seekers were

suspended. Due to closed borders, a historically low number of asylum seekers

entered Denmark (1515). Any cases that did occur were carried out online.

90

87 Council of Europe, Report to the Danish Government on the visit to Denmark carried out by the

European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment (CPT), 7 January 2020, p. 53-54.

88 Council of Europe, Response of the Danish Government to paragraph 117 of the report of the

European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Denmark from 3 to 12 April 2019, 3 March 2020.

89 Dunja Mijatovic, Report following her visit to Denmark from 30 May to 2 June 2023, Commissioner

for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, Council of Europe, 25 October 2023.

90 European Commission, “Denmark: How has COVID-19 affected migrants?,” 20 November 2020.

20

4 Access and national

asylumprocedures

The Danish Asylum Procedure

Most asylum seekers arrive in Denmark without prior consent to enter the

territory, due to the difficulty of obtaining visa for humanitarian purposes.

91

In2002 Denmark abandoned the policy option of asylum on diplomatic posts.

92

Any foreign national who is in

93

or has entered Denmark, whether illegally or

with a visa, can apply for asylum. As stated in the paragraph on the applicable

international legal framework, the grounds for asylum are based on Denmark’s

international legal obligations.

94

Once in Denmark, a person who wants to apply for asylum has to register with

the (border)police or at Reception and Application Centre Sandholm in Allerød.

The practical and humanitarian work of the reception centre falls under the

Danish Red Cross, while the Danish police, the Danish Immigration Service, and

91 Danish visa rules are based on nationalities. Countries whose citizens must hold visas in order to

enter Denmark are divided into five main groups. Different guideline requirements for obtaining

a visa apply to each group and the groups are based on the overall risk of a citizen remaining

within the Schengen countries after the individual’s visa expires. See The Danish Immigration

Service; Seealso Michala Clante Bendixen “Hvor mange kommer, og hvorfra?,” Refugees DK,

29Septermber 2023.

92 See in this respect Gregor Noll, Jessica Fagerlund and Fabrice Liebaut, Study on the feasibility

of processing asylum claims outside the EU against the background of the Common European

Asylum System and the goal of a common asylum procedure, Danish Institute for Human Rights

andEuropean Commission, 2020.

93 This means that people already with a Danish residence permit, often based on family

reunification, can also apply for asylum, The Danish Immigration Service, “Adult Asylum Seeker –

Who can apply for asylum?”.

94 Danish immigration authorities can grant a temporary residence permit as a refugee in line with

three provisions of Article 7 of the Danish Aliens Act: 7.1) Convention status or K-status: meeting

the UN Refugee Convention’s definition of refugees, linked to fear of being persecuted for reasons

of race, religion, nationality, membership of a social group or political opinion. 7.2) subsidiary

protection status or B-status: due to risk of torture or inhumane treatment in the country of

origin, or 3) temporary protection status: the situation at the country of origin is characterized by

indiscriminate violence and attacks on civilians. See also Danish Refugee Council, “Getting Asylum

in Denmark.”

21

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

the Danish Refugee Appeals board are in charge of the case management.

95

The initial phase of the procedure starts with registration of the asylum seeker

after which they will be issued a specific card which serves as a personal ID.

Usually they will after a couple of days be provided with accommodation in an

asylum reception center, determined by the DIS. Subsequently asylum seekers

are summoned by the DIS to fill out a written asylum form on the person’s name,

country of birth, residence, family, reasons for fleeing, fear of return, countries

travelled through etc, which can be done in any language. As soon as possible,

this is followed by the first personal interview, so-called “OM-samtale”, with

the DIS and an interpreter at Sandholm, to establish the travel route and to

determine the motivation for seeking asylum.

On the basis of the written application and the interview, and a search in the

common European fingerprint register, the DIS will determine whether the

application should be processed in Denmark or another country according to

the Dublin rules: this is solely an admissibility procedure without an examination

of the merits of the case (section 29a Aliens Act)

.

96

The Dublin procedure is laid

down in section 29a of the Aliens Act. If the asylum seeker has been granted

international protection in another Member State in the European Union, the DIS

can decide to reject the processing of the application in accordance with the

Danish Aliens Act section 29b. A decision to reject the processing of an asylum

application can be appealed to the Refugee Appeals Board. The appeal does not

have automatic suspensive effect, except for Dublin cases.

97

In 2022, a transfer decision to another Dublin agreement country was made in

472 asylum cases.

98

95 Danish Red Cross, “What we do in the asylum department.”

96 The Danish Immigration Service, Tal og fakta på udlændingeområdet 2021, 2021, p. 9.

97 EDAL, “Country Profile-Denmark,” 1 February 2018. See also for overviews of the Danish asylum

procedure: DRC, “The Danish Asylum System,” and DRC, “Overview of the Danish asylum

procedure,” January 2020.

98 The Danish Immigration Service, “Tal og fakta på udlændingeområdet 2022,” 2022, p. 9, Table A.2.

22

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

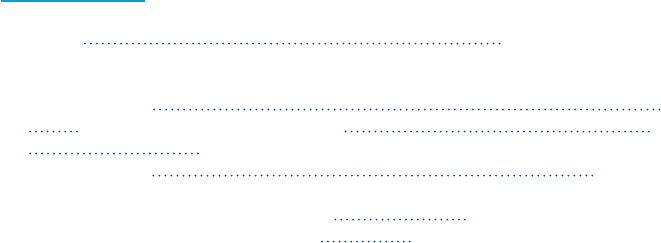

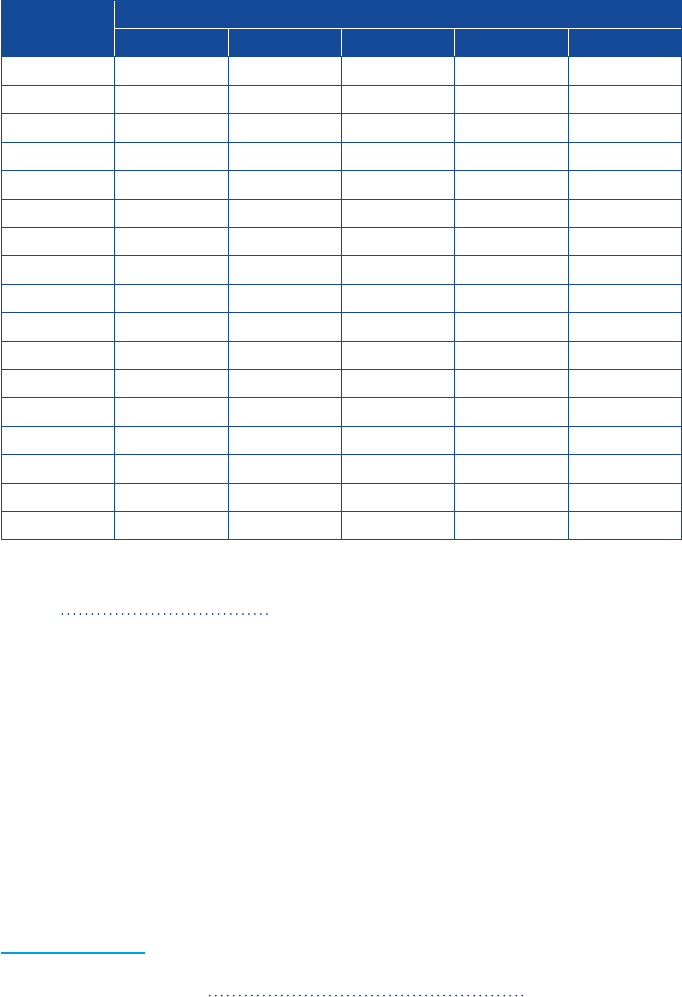

Asylum Procedure

Registration + finger prints

with the police

Filling out asylum form

1. interview (OM)

with Immigration Service

Dublin Procedure

Another country

may be

responsible for

the case

Humanitarian

Residence Permit

may be an option,

processed by the

Integration

Ministry

Manifestly

Unfounded

Danish Refugee

Council can veto,

if so, the case

goes to Normal

Procedure

Appeal

Case goes

automatically to

the Refugee

Appeals Board,

state provides a

lawyer

Manifestly

Well-founded

Obvious reasons

for asylum

Normal Procedure

2. interview

Preliminary

rejection

Asylum

Asylum

Final rejection

Final rejection

Source: Refugees DK

If the DIS has established that the application is admissible and will be processed

in Denmark, the case can be decided to fall within the manifestly unfounded

procedure (ÅG), expedited manifestly unfounded (ÅGH), or manifestly founded

23

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

procedure.

99

The latter is a faster procedure deemed for asylum applications with

a high eligibility rate, most often categorized on the basis of the country of origin

(such as the Syrians in 2015, before the policy change). These cases are often

processed within a few months. If the application is considered well-founded,

a residence permit with the according status is granted and a municipality will

be assigned as the responsible actor for the integration process of the refugee/

asylum permitholder.

In the ‘manifestly unfounded procedure’, applications are processed that are

likely to be rejected. This would be the case if an asylum seeker has no valid

grounds for seeking asylum, or if the applicant’s grounds for seeking asylum do

not warrant protection (article 53 Aliens act). If the application is likely to be

rejected in the ‘manifestly unfounded procedure’, the case will first be put to

the Danish Refugee Council (DRC).

100

The DRC has the opportunity to veto the

DIS’srejection following an interview with the applicant.

101

In 2022, the DRC did

not agree with the DIS’s decision of manifestly unfounded cases in about 11% of

the cases.

102

If that is the case the asylum seekers person receives the normal

right to appeal to the RAB. If the DRC agrees with the DIS, the rejection is final

without the possibility of appeal.

103

The expedited version of this procedure is based on a list of certain (safe)

countries of origin which hardly ever lead to asylum protection.

104

This list

of countries is regularly reviewed by both the DRC and the DIS. These cases

are often decided within a few days with no possibility for appeal to RAB.

However,involvement of DRC should ensure that the case is processed in

theright way.

99 The Danish Immigration Service, “Processing of an asylum case.”

100 See supra note 24 for an explanation of the role of this NGO.

101 Danish Refugee Council, “The Danish asylum procedure – phase 2,” December 2015.

102 The Danish Immigration Service, Tal og fakta på udlændingeområdet 2022, p. 69, attachment 3.

103 Ministry of Immigration and Integration, “International Migration Denmark, Report to OECD,”

November 2022, p. 38.

104 The Danish Immigration Service, “Processing of an asylum case,”; Countries on this list are Albania,

Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, Georgia (with the exception of LHBTI persons

and persons from Abkhazia and South-Ossetia), Iceland, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Mongolia,

Montenegro, New-Zealand, Northern Macedonia, Norway, Russia (with the exception of ethnic

Chechens, LHBTI persons, Russian Jews and persons who are politically active and mistreated

bythe authorities, Serbia, USA and Switzerland.

24

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

Most of the asylum applications are on the individual merits assessed and

decided in the regular procedure. In 2022, Denmark received 4,597 asylum

applications

105

of which 30.52% (1,043) were granted residence permits.

106

Of thegranted residence permits issued in asylum cases, 509 were granted a

K-status, 71 a B-status, and 50 received temporary protection status (as Syrians

no longer receive that status).

107

Next to this asylum process based on international protection grounds, an

asylum seeker can apply for a residence permit on humanitarian grounds in

accordance with Article 9b.1 of the Danish Aliens Act. This can also be submitted

after a rejection of the asylum application by the DIS. As a separate procedure,

this application is submitted to and processed by the Ministry of Immigration

and Integration. The Danish parliament stated that a humanitarian residence

permit should be an exception and is only to be granted in very specific cases,

for example a severe deterioration of a serious handicap upon return to country

of origin.

108

Of note, this is very rarely granted, with only 2 cases leading to an

approved residence permit in 2022.

109

Formally, and in line with international refugee law, the burden of proof in

assessing the merits of the asylum claims is shared between the applicant and

the government, whereby the DIS in first instance and the Refugee Appeals

Board in the second has to motivate their assessment and decision. Information

is initially gathered through the written application and interviews with the

asylum seeker. The individuals’ credibility and individual risk is assessed, in

105 The Danish Immigration Service, “Tal og fakta på udlændingeområdet 2022,” 2022, p. 10,

tableA.1.2.

106 Ibid., table A.4.

107 Ibid.

108 The Danish Immigration Service, “Apply for residence permit on humanitarian grounds,”

August2018.

109 See supra note 93. Unaccompanied minors who seek asylum (UMAs) are considered a specifically

vulnerable group. Their asylum applications are in general processed within a short timeframe

and they are housed in special accommodation centers. If the minor is initially viewed as too

immature for the asylum process, the asylum procedure will be postponed until they are deemed

as mature enough to understand and handle the procedure (The Danish Immigration Service,

“Unaccompanied minor asylum seeker”) If there is doubt about the proclaimed age of the minor

asylum seeker – thought to be older than 18 years – an age survey, including medical assessment

will be conducted to get physical proof of their age. In 2022, the DIS conducted age tests, of which

64% were assessed to be older than 18 years.

25

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

light of general ‘Country of Origin Information’ reports. The risk assessment in

practice has been subjected to criticism for being illogical and unpredictable

– specifically regarding the decision which protection status is granted in

which case. Forexample, in 2021, 34% of granted residence permits for Syrians

were based on Article 7(1)

110

, whereas in 2022, 62% of Syrians gained the same

status.

111

The credibility assessment has furthermore been declared too tough,

following its increasingly strict policies. In comparison to other EU countries, in

the first quarter of 2023, Denmark was 19

th

in the EU in terms of asylum seekers

per capita. This is a drastic drop to Denmark’s 5

th

place in 2014.

112

To acquire a permanent residence permit, strict requirements must be met,

alsoas a consequence of the recent national legislative asylum reform as part

of the paradigm shift. The most important preconditions are that a person has

legally resided in Denmark for at least 8 years, whereby the period during the

asylum process does not count, passing the Danish 2 language test, and having

been in regular full-time employment for at least 3.5 years.

113

Accommodation

Depending on the type and/or phase of the procedure, asylum seekers are

transferred to a reception center. Upon arrival, applicants stay in the Sandholm

center. Dublin claimants often stay in Sjælsmark which is a return centre run by

the Prison and Probation Service until they are transferred. During the asylum

procedure asylum seekers reside in one of the accommodation centers which are

mostly in Jutland.

114

The DIS is responsible for providing and operating reception and accommodation

centers for asylum seekers and irregular migrants based on the Danish Aliens Act

110 The Danish Immigration Service, “Tal og fakta på udlændingeområdet 2021,” 2021, p. 67,

attachment 3.

111 The Danish Immigration Service, “Tal og fakta på udlændingeområdet 2022,” 2022, p. 69,

attachment 3.

112 Bleona Restelica, “Denmark registering fewer asylum seekers than most other EU member states,”

18 April, 2023.

113 Ministry of Immigration and Integration, “International Migration Denmark, Report to OECD,”

November 2022, p. 52.

114 After rejection of a claim, and when considered not cooperative with respect to return to the

country of origin, rejected asylum seekers are moved to return and deportation centre Avnstrup

(families) or Sjælsmark or Kærshovedgård. Ellebæk is a closed center with the aim of forced return

(‘motivational measure’). See also under ‘return’.

26

Shifting the paradigm, fromopt-out to all out? | Clingendael Report, February 2024

section 42 a, subsection 5. However, in practice about half the accommodation

centers are run by the Danish Red Cross, and the rest by municipalities.

115

Services such as a basic cash allowance, healthcare, education for adults and

children, accommodation, and clothing packages are provided for (DIS) during

the asylum procedure, unless the asylum seeker has sufficient own means.

116

Based on the ‘jewelry law’, asylum seekers must inform the authorities upon

arrival if they carry possessions worthy of 10.000 Danish kroner (1344 euro’s).

117

If this is the case, these valuables will be seized to cover the accommodation

expenses.

Accommodation centers are open centers, with security control for visitors.

All adult asylum seekers must enter a personalized contract with the

accommodation center they have been assigned to. This agreement includes

the context of daily tasks the asylum seeker is required to do, such as cleaning.

Thematerial rights can be diminished or revoked in case of non-compliance with

the contract, or in case of any other kind of misbehavior.

Rooms and kitchen are often shared. If the application case will be processed

in Denmark, the asylum seeker has to complete introductory basic Danish

language and Danish cultural and social conditions courses.

118

Accommodation

centers have ‘in-house activities’ and “out-of-house activities” such as unpaid

job-training programs.

119

However in recent years, the centers have been moved

more and more to rather isolated and thinly populated areas, which makes it

increasingly difficult for asylum seekers to connect with Danish society and to

keep themselves sufficiently occupied. In practice, asylum seekers often have

to move from one center to the other, which is problematic, e.g. schooling for

children, medical care, access to psychologists etc.

120

115 Ministry of Immigration and Integration, “International Migration Denmark, Report to OECD, 2022,

p. 38. Also, possibility for private accommodation under certain rules approved by DIS, but is not

often used.

116 The Danish Immigration Service, Conditions for Asylum Seekers.