The Impacts of Home-Court Advantage in the NBA

Wesley Chang & Michael Ran

Professor Gary Smith

Pomona College

Department of Economics

1 May 2021

Chang and Ran

1

Abstract

Objective. In the 2019-2020 NBA season, the NBA invited the top teams to compete in a

“bubble” that stripped away the traditional home-court advantages of fans, travel, court

familiarity, and referee bias. This bubble provided a natural experiment where we could analyze

the effects of home-court advantage. In this paper, we were interested in finding the root causes

of home-court advantages and their precise impact on wins, free throw shooting percentages, and

fouls called.

Methods. To investigate the causes of home-court advantage, an analysis of over twenty

years of NBA data was used. We ran logistic regressions on wins, and linear regressions on free

throw shooting percentages and fouls called.

Results. The number of fans, travel distance, and quality of team all had effects on home-

court advantage. In the bubble, the away team’s win percentage increased by 3 percentage

points. The free throw shooting percentages increased by 2.3% and there were 9% fewer fouls

for the away team and 5% fewer for the home team.

Conclusions. Although fans, travel, and familiarity all affect home-court advantage, the

largest factor is the quality of teams. This suggests that teams should focus on their performance

and development, worrying less about the location of their games.

Chang and Ran

2

I. Introduction

“Bryant for the win… BANGGG!” 20,000 rowdy fans scream and cheer as their team

earns a victory in the National Basketball Association (NBA) playoffs. Home-court advantage is

the psychological and sometimes biased benefit that the home team experiences due to the

familiarity of the arena and encouragement of their fans. In Major League Baseball, the home

team has a better understanding of the dynamics of their field and bats last. In the National

Hockey League, the home team can have more favorable matchups with “last-change” rules and

can have face-off advantages. In the National Football League, the types of stadiums—indoor or

outdoor/turf or grass—influence how athletes play and prepare. In the NBA, there are no

possession advantages, but there are other factors of floor design and lighting that benefit teams.

Out of the four major American sports, home-court advantage has the largest effects on NBA

teams, with the home teams winning 58-60% of their regular-season games, compared to low-

50% in the other major sports. NBA teams have a goal of winning as many regular-season games

so that they may have home-court advantage in the playoffs, where the higher-seeded team has

the benefit of playing at home four times compared to three.

In 2020, the season abruptly stopped due to the novel Coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19).

Approximately half a year later, the NBA invited the top teams to compete in a “bubble” to

finish a modified regular season and playoffs without fans, travel, and distractions. With this

natural experiment, the impacts of home-court advantage were stripped away, and as a result,

there were games with the biggest upsets in over 27 years with the Brooklyn Nets (predicted

18.5-points spread) defeating the Milwaukee Bucks and a fifth-seeded Miami Heat advancing to

the NBA Finals. The start of the new 2020-2021 season has also been unique, with limited to no

Chang and Ran

3

fans at games (with a few stadiums allowing a limited number of fans). So far 80% through this

season, approximately a third of the teams have a better record away than at home.

Despite the results of home-court advantage, researchers have not directly tested whether

home-court advantage has held given the additional data that these past two unique seasons

provide. This paper will contribute to the existing research incorporating new data on home-court

advantage. Our goals are to find the root cause of home-court advantage—may it be fans, travel,

the strength of teams—and see their precise influences on wins, free throw shooting percentage,

and referee fouls called. Upon finding our results, we will offer suggestions on league policies to

create more equal playing terms in a year where only some arenas have fans. We hypothesize

that the home court phenomenon is legitimate and is most largely impacted by crowd sizes and

travel time. Accordingly, we also hypothesize that in the bubble, home-court advantage will have

less of an effect on wins, free throw shooting percentage, and fouls without the impacts of

crowds and travel.

This paper is structured as follows: in Section II, we provide a brief overview of relevant

literature. We describe our methodology in Section III. In Section IV, we will test our data and

evaluate the results of our findings. Section V discusses the tests, relevant trends, and further

implications on the NBA. We will conclude with a summary of the major results of our research.

The appendix section will include the key highlights of our results, along with graphical data.

II. Literature Review

It is widely agreed upon that athletes and home teams have a greater probability of

winning at home. Stefani (2008) also concluded that home-court advantage is even stronger

during the high-pressure championship and playoff games, compared to regular season seed

Chang and Ran

4

games. Given the quantifiable data that proves the existence of home-court advantage, most

work focuses on the causes of the advantage. This home-court advantage phenomenon is seen in

any organized sport; however, it varies among sports. Researchers point out psychological

phenomena, crowd effects, facility/location familiarity, travel factors, and officiating decisions

that impact home-court advantage (Carré et al., 2006; Carron et al, 2005; Nevill and Holder

1999; and Pollard, 2008). In the following paragraphs, we will synthesize each of these effects.

Psychological factors play a role in the preparation and mindsets going into games for

both players and coaches. Some argue that it provides a placebo effect for players’ performances

and mental attitudes, giving the home team a self-perpetuating benefit because they feel like it

does (Belhumer, 2013; Pollard, 2008). Athletes also want to protect their home court,

demonstrated by a territorial response that boosts their testosterone levels when they play at

home while having a decreased testosterone in away games (Carré, 2009; Carré et al., 2006;

Neave and Wolfson, 2003; Pollard, 2008). Additionally, players were also shown to have higher

pre-game cortisol (stress) levels when playing at home, suggesting that they may have pressures

to perform at home (Carré, 2009).

One of the most studied factors within home advantage is the research on crowds and

attendance. Research has suggested that a primary benefit of home-court advantage is

attributable to the social support from the audience (Pollard, 2008; Schwartz and Barsky, 1977).

Home teams are more successful when they play in front of a large fan base that supports and

encourages them. Due to the closeness and compactness of fans in indoor arenas, fans provide

extra motivation with amplified noise (Schwartz and Barsky, 1977). Greer (1983) found that for

both home and visiting teams, crowd reactions have a direct correlation to their performance—

specifically, the louder the crowd noise, the better the performance of the home team, and the

Chang and Ran

5

worse the away team performs. Goldman and Rao (2012) have found that the home teams are

stronger with aggressive, effort-based plays, like offensive rebounding in pressure-packed

moments (end of close games), with the home crowd cheering them on. Meanwhile, the road

team shows no relationship between performance and pressure, demonstrating an asymmetric

impact on the crowd and audience.

A team’s familiarity with the city and arena also influences their performance. Pollard

(2002) tested this theory by analyzing teams that moved arenas. He found that teams had a

higher winning percentage in their final year before moving arenas, which resulted in a roughly

25% loss of home-court advantage when they relocated to a new, unfamiliar court. Additionally,

each court has its distinct advantages and feel. For example, the Brooklyn Nets have a unique

herringbone pattern, the Charlotte Hornets have lighter/darker patches forming a honeycomb

design, the Orlando Magic have a parquet pattern, and many teams have two-toned colored

floors. Lighting reflects on each piece of the flooring in a different manner and players may be

more accustomed to one over another (Newcomb, 2015). Most uniquely, the Boston Celtics’ TD

Garden is a court that does not use the traditional hard maple for their floors like all other teams.

In contrast, their floor uses red oak which has a different feel and bounce (with red oak being

12% lighter than normal maple). As a result, it takes more energy to retain the same ball bounce,

with some athletes preferring a harder surface and some preferring a lighter surface.

Teams also prefer to host games because they want to be in their familiar environments,

avoid travel, and sleep in their own beds. Traveling impacts rest and the schedule of games

played in the NBA. Goumas (2013) has found that home-court advantage is intensified by

20% for each time zone crossed due to factors like jet lag. Additionally, teams that travel more

than 200 miles for their games have a higher probability of a loss when playing at an opponent’s

Chang and Ran

6

arena (Carré et al., 2006). Studies have also shown that due to the NBA’s scheduling of road

games, the lack of rest for the road team is an advantage for the home team (Entine and Small,

2008). Traveling to teams with the highest elevation—the Denver Nuggets and the Utah Jazz—

prove to be the most difficult for teams (Lopez et al., 2017). In a recent study utilizing data from

the NBA bubble, without travel, team shooting accuracy and rebounding increase, with a link to

the team’s steadiness of circadian rhythm (McHill and Chinoy, 2020).

Referee bias and decision making is an additional factor that contributes to the benefit of

the home teams. Even though referees do not have their designated home court, their

psychological states are considered responsive to the support of the home audience: they do

not like to be booed so they are inherently biased on calls. Officials may want to appease a

crowd and may respond to crowd noise and reactions in a way that favors the home team

(Downward and Jones, 2007). In an experimental study isolating the sound and noise of crowds,

officials have been found to favor the home teams, awarding them with 15.5% fewer foul calls

compared to the away team (Nevill et al, 2002). The location of the game feeds into the

psychological moods of the referees (Carron et al., 2005) and the crowd composition and their

proximity to the field affect the neutrality of refereeing (Dohmen, 2008). In another study

using the NBA’s database of calls from the last two minutes of close games (games within 5

points or less), researchers have found that the home team benefits the majority of the time from

correct calls, incorrect no-calls (referees letting teams get away with infraction), and incorrect

calls (referees making a mistake on their calls). With more incorrect calls and a higher quantity

of calls made against the away team, this study reaffirms that due to the judgmental crowds, the

officials are more influenced (Roeder, 2017).

Chang and Ran

7

Overall, the existing studies show that fans and the game location has an impact on the

outcomes of teams and players. Although the research highlights the causes, there is no clear

research that shows the exact outcomes on performance. Our work will contribute to the existing

NBA home-court advantage literature while adding new data.

III. Methodology

III.i. Methodology for Data Collection

To determine if there are substantial effects of home-court advantage in the NBA, we

collected and analyzed data from the most recent twenty years of the league (2000-2021),

focusing on data from the NBA bubble (2020) and this COVID-influenced season (2020-2021).

All game logs and attendance records from these years were collected using two different scripts

that scraped basketball-reference.com with Python. Once the data was collected locally, we ran

numerous statistical tests on the data to try and quantify the effects of home court advantage. To

gather data on the travel distance between arenas so that we could test our theory regarding

travel’s impact on gameplay, we imputed the coordinates of each team’s arena to calculate the

distance between stadiums.

III.ii. Methodology for Tests

When evaluating home-court advantage, important factors include the win percentage,

free throw percentage, and fouls called. We ran three regressions based on these factors:

Y

wins

= α + β

1

DIST + β

2

FAN + β

3

BUB + β

4

HOME + β

5

TSCOR

+ β

6

OSCOR + β

7

WINMA + ε

Y

free throw percentage

= α + β

1

DIST + β

2

FAN + β

3

BUB + β

4

HOME + β

5

TSCOR

+ β

6

OSCOR + β

7

FTMA+ ε

Y

fouls

= α + β

1

DIST + β

2

FAN + β

3

BUB + β

4

HOME + β

5

TSCOR

+ β

6

OSCOR + β

7

FOULMA+ ε

Chang and Ran

8

Where

Y

wins

= the predicted value on win percentage

Y

free throw percentage

= the predicted free throw percentage

Y

fouls called

=the predicted number of fouls called

DIST = Travel distance from previous game arena to current game arena

FAN = Number of fans at the arena

BUB = 1 if game played in NBA Bubble, = 0 if game is a regular NBA game

HOME = 1 if game is played at home, = 0 if played at opponent’s arena

TSCOR = 10-game moving average of the team’s points scored

OSCOR = 10-game moving average of the opponent’s points scored

WINMA = 10-game moving average of the team’s win percentage

FTPMA = 10-game moving average of the team’s free throw percentage

FOULMA = 10-game moving average of the team’s number of fouls

To test the effects of fans, we measured them on a spectrum where the away team has an

X number of fans. The home team would have its inverse, -X fans. For example, in a game

between the Houston Rockets (home) and the Los Angeles Lakers (away), the Rockets would

have -16,000 fans, with the Lakers having 16,000 fans rooting against them.

The recent performance of the teams also impacts how they perform. Stronger teams

performing well both at home and on the road may have more consistent numbers. To control for

the quality of the teams, free throw percentages, and the number of fouls, we calculated a

moving average of each team’s last ten games. Our rationale for looking at the last ten games is

to work with numbers corresponding with the NBA’s official standings data points (L10) and

Chang and Ran

9

also using an aggregation of the last three “Power Rankings,” which ranks teams each week. We

also used the ten-game moving average of the team’s score and their opponent’s score to have a

sense of the average numbers each team puts up to gain additional data of their quality. In doing

so, we were able to filter out the “noise” from unexpected results or upsets. Using the moving

average data, the impacts of the upsets and short-term fluctuations of a team’s performance over

a specified period are mitigated. This was also applied to data on free throw percentage and fouls

called by referees.

To test the data on wins, we ran logistic regressions. To find the probability of classifying

a game as a win or a loss, we looked at how the independent variables affect wins. For our tests

on free throw percentage and fouls called, we ran linear regressions. We wanted to predict the

values of continuous variables of the free throw trends and numbers of fouls.

IV. Results

IV.i. Results from Regular NBA Seasons with Fans at Full Capacity

IV.i.1. Results from the Win Regression

Figure 1 (column 1) shows the results of the logistic regression on wins. To better

understand the coefficients of the regression, we exponentiated the model’s coefficients which

can be found in Figure 2. A key takeaway from this model is the importance that being the home

team plays on a team’s win percentage. This model suggests that the home team has a 51%

higher chance of winning ceteris paribus (with statistical significance at the 99% level). Another

variable found to be incredibly statistically significant in this model was the number of fans at a

given game. What this regression shows us is that for every 1,000 fans in the stadium, the

probability that the away team wins decreases by 1%. Conversely, the home team’s probability

Chang and Ran

10

of winning increases by about 1% for every 1,000 fans in the stadium—demonstrating the

significant impact that fans have on the outcome of a basketball game. When looking at each

team’s moving win percentage, our proxy for the caliber of a team, we notice that this variable

holds most of the explanatory power of the model which makes sense given that the most

important factor that determines a game is the respective quality of each time. Had this not been

the case, a team full of amateurs would potentially stand a chance against a professional team if

they were the “home” team—a hypothetical that basketball viewers can agree is unrealistic.

IV.i.2. Results from the Free Throw Percentage Regression

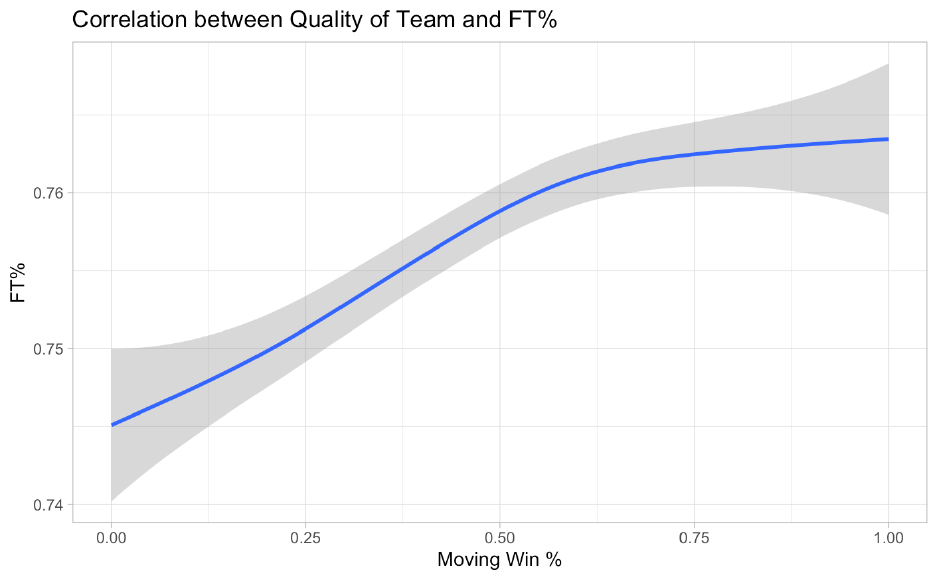

The results from the free throw percentage regression (Figure 1, Column 2) also support

our hypothesis. The coefficients for the moving team score and the opponent’s team suggest that

teams that score more will have relatively higher free throw percentages than those who do not

and that teams who give up more points will have relatively lower free throw percentages, ceteris

paribus. The intuition behind this is that these two variables are serving as a proxy of the strength

of a team. As shown in Figure 3, good teams historically tend to shoot free throws at a better rate

than poor teams, which explains why we see the opposite directions (positive vs. negative) for

these coefficients. The positive coefficient of the bubble dummy variable also suggests teams’

free throw percentages increased by playing in the bubble. We also find that a team’s free throw

percentage is, surprisingly, predicted to be almost 1% lower when playing at home which could

potentially be explained by the added pressure of shooting in a quiet setting with the hopes of

thousands of fans on your back. However, it is important to note that this model struggled to

find statistical significance for nearly all independent variables, so the coefficients are not

necessarily accurate. The only two variables deemed statistically significant were a team’s

Chang and Ran

11

moving average free throw percentage average and the distance the team traveled to the game.

The significance of distance can possibly be explained by how fatigue impacts a given player’s

ability to shoot free throws. However, this coefficient suggests that 1,000 miles of travel only

decreases a team’s average free throw percentage by a fifth of 1%, a negligible difference. So, in

other words, the thing that most highly impacts a team’s free throw percentage for a given game

is the team’s ability to hit free throws—regardless of the environment that they find themselves

playing in. Not only is this variable extremely statistically significant, but its coefficient is .98,

meaning a team with a hypothetical perfect free throw percentage average (100%) would be

predicted to make 98% of their free throws in a given game ceteris paribus. None of the other

independent variables match the explanatory power of this proxy for a team’s quality of free

throw shooting; other variables are only able to impact a team’s projected free throw percentage

by less than a few percentage points.

IV.i.3. Results from the Fouls Regression

The fouls regressions support our hypothesis that fans influence the number of fouls

called against the away team (Figure 1, Column 3). We find that being the home team decreases

the number of foul calls that a team is predicted to have by about half of a foul. Additionally, we

found that, as the away team, there is a positive correlation between fans at the stadium and fouls

called. For every 20,000 fans rooting against the away team, there is almost 1 more foul called

against the team. Similar to the other regressions, the variable with the largest explanatory power

is the team’s moving average of fouls called against them. Teams that have a history of playing

physical and fouling a lot are much more likely to have more fouls called on them in a given

game.

Chang and Ran

12

IV.ii. Results from NBA Bubble Season and with None/Minimal Fans

The three aforementioned regressions align with our predictions that the NBA Bubble

minimizes the effects of distractions for teams, players, and referees in terms of wins, shooting

percentage, and the number of fouls called. Despite playing in the bubble, there was still a

designated home and away team. During these games, the teams would still have their team logo

on the courts and there would be virtual fans and sound effects that mimic the game sounds.

The away team’s winning percentage increased by 3 percentage points. In the bubble, the

free throw percentages increased by 2.3%, with the home team increasing by 2.1% and the away

team increasing by 2.4%. Without direct fans’ impact, the percentage chance of a player making

the free throw is increased for both teams. Furthermore, without the influence of fans, the

number of fouls called on teams is lowered. There were 9% fewer calls for the away team and

5% fewer calls for the home team, likely still influenced by the sound effects.

The results from the two-sample difference-in-probabilities test are quite telling. When

looking at the free throw shooting p-value table (Figure 4), we see that while there is no

significant difference between how teams shoot free throws at home and on the road, there is

incredible statistical significance in the difference between free throw shooting inside of the

bubble and outside of the bubble for teams playing at home and on the road. The personal foul p-

value table (Figure 5) reinforces our prior theories about how officiating bias could impact

games. The table shows us that there is a statistically significant difference between personal

fouls called on home and away teams outside of the bubble, personal fouls called on home teams

in and out of the bubble, and personal fouls called on away teams inside and outside of the

bubble. The only value in the table without statistical significance is looking at the difference in

fouls called on home and away teams in the bubble—a fascinating result. The results from the

Chang and Ran

13

win p-value table (Figure 6) indicate that the difference in probabilities of winning for home and

away teams outside the bubble is statistically different. While the difference in win probability is

still significant for home and away teams, it should be noted that the difference is much less

statistically significant.

V. Discussion

In our study, we were able to test the effects of home-court advantage in a normal NBA

season and also the effects in an isolated and controlled season without fans and travel. Our final

results were relatively in line with our hypothesis with most of the independent variables moving

in the direction we predicted.

Notably, the moving average data for win percentage, free throw percentage, and fouls

called are the biggest factors for each team and game. This outcome shows that the main

influence on predictions of future games is the recent performance of previous games. In other

words, a team’s ability is the strongest advantage/disadvantage for factors that affect the

magnitude of home court. The higher-seeded teams have a higher percentage of winning no

matter what location they play in, the better shooting teams consistently shoot higher free throw

percentages at any arena, and teams that typically foul more may continue to foul more. This

implies that the quality of the teams, either home or away, can have a strong dictation of the

outcomes of wins, free throw shooting, and fouls called.

In the NBA bubble, team’s free throw percentages have increased. This factor could be

attributed to the lack of fans. With a lack of distractions and a quieter arena, players may be able

to better focus on their shot. There are fewer interferences for both teams without distractions

and the pressures of failing. This may also be due to depth perception: without fans, all the light

Chang and Ran

14

in the arena is focused on the court, leaving the stands dark, which makes the net easier to see.

Additionally, there are also fewer foul calls in the bubble with no fans. This is in line with the

literature that suggests that home crowds influence referees in making calls.

These factors show that home-court advantage has less influence with none/few fans. In a

unique season like this year, teams may have other inspiration to perform well in the regular

season, perhaps to receive favorable matchups against teams of lower seeds, rather than fighting

to play at home.

However, there are also unexpected results from the regressions we ran. Within the wins

regression, the increased travel for games led to a positive outcome on wins. Literature suggests

that fatigue from travel and confusion with changed circadian rhythm should cause a decline in

performance, yet our results show that distance is a positive factor for winning percentage, which

cannot be explained by the existing literature. This factor may be because the distance also

includes flying back home, where the factors of playing at home outweigh the travel fatigue.

Our results also deviated where playing at home may not benefit free throw percentages. The

existing literature describes home crowds to benefit and boost the home team. Yet, our results

show that free throws decline. This may be due to how fans are more effective in energy plays,

but with focused shooting, the subtle movement of fans and added stresses and pressures to

impress may lead to choking. Another factor to note is that the sample size of games with

limited/no fans is continuously evolving with 5-10 games played each night. The later we run

each regression, the more data we have on the games for the 2020-2021 season.

Ultimately, in a unique season this year with the states dictating the fan attendance of

games, we propose two different solutions to implement during the playoffs. First, teams can go

back into a bubble, like last season where the effects of home-court advantage are stripped away.

Chang and Ran

15

Second, arenas that are allowed fans should limit their fans based on the maximum capacity of

both teams. For example, if one team has a capacity of 5,000 fans and another has a capacity of

750 fans, both teams must limit capacity to 750 to equalize the effects. In the case that some

arenas do not have fans, the league should have policies where the team with fans have them sit

further back in the stands so their proximity and noise levels less affect the players’ performance.

These fans should also sit to the sides of the arena, where they do not affect the concentration of

players when they shoot free throws. These policies for the 2021 playoffs will still maintain the

effects of home-court advantage for the higher-seeded team but will lessen the impact that fans

have on a team. Referees will continue to be less biased and athletes will have fewer impacts due

to the crowd.

VI. Conclusion

Home-court advantage has always been a motivating factor for NBA teams to perform

well. With a better record than their opponents, teams have the home-court advantage in the

playoffs, where they may reap the benefits of playing an additional game at their familiar arena

with their supportive fans. The positive effects of playing at their home court also improve some

player’s mental preparedness. However, home-court advantage is not always available or

prevalent, as reflected in last year’s bubble season or this year’s COVID-restricted season.

Our results prove that our initial hypothesis that fans and travel influence home-court

advantage are correct, but we found that the quality of the teams is still the most important

attribute. The biggest factor is still a team’s dominance and consistent play in influencing wins,

free throw shooting, and fouls called, rather than the location or influence of others. The NBA

bubble highlighted these factors, demonstrating that in an equal playing field, referees may call

Chang and Ran

16

less biased calls, but a team’s numbers are what will have the most impact on winning the

games. Teams should not rely on having the home court to win games but focus on each statistic

each game.

Chang and Ran

17

Appendix

Figure 1: Regressions

Regression Results

(1)

(2)

(3)

Win

FT %

Fouls

Intercept

-2.642***

0.0173

1.0606*

(-11.504)

(1.543)

(2.476)

Team Score (MA)

-0.003

9.06E-05

-0.005

(-.065)

(.940)

(-1.225)

Opponent Score

(MA)

-0.002

-6.72E-05

0.0031

(-.052)

(-.766)

(.788)

Fans

-1.453e-05***

-1.95E-07

-3.48E-06

(-3.883)

(-1.292)

(.545)

Distance

3.69E-05

-1.78E-06

-2.53E-05

(2.206)

(-2.700)**

(-.900)

Bubble

0.0511

0.0048

-0.0849

(.558)

(1.298)

(-.538)

Home

0.4149**

-0.0068

-0.4828

(3.116)

(-1.278)

(-2.121)

Win % (MA)

4.9147***

(35.061)

FT % (MA)

0.9802***

(82.156)

FT % (MA)

0.9704***

(93.329)

Observations

26,544

26,544

26,544

z and t statistics in parenthesis:

* p < 0.05, ** p < .01, *** p <.001

Chang and Ran

18

Figure 2: Exponentiated Win Coefficients

coef

Intercept

0.071219

Team Score (MA)

0.9997

Opponent Score

(MA)

0.9998

Fans

0.999985

Distance

1.000037

Bubble

1.052428

Home

1.514219

Win % (MA)

136.27842

Chang and Ran

19

Figure 3: Quality of Team vs Free Throw Percentage

Chang and Ran

20

Figure 4: Free Throw Shooting P-Values

Free Throw P Values

Not in Bubble

In Bubble

Away

Home

Not in Bubble

Home

0.474

0.000***

In Bubble

Away

0.000***

0.798

* p < 0.05, ** p < .01, *** p <.001

Figure 5: Personal Foul P-Values

Personal Foul P Values

Not in Bubble

In Bubble

Away

Home

Not in Bubble

Home

0.000***

0.000***

In Bubble

Away

0.000***

0.272

* p < 0.05, ** p < .01, *** p <.001

Figure 6: Win P-Values

Win P Values

Not in Bubble

In Bubble

Away

Home

Not in Bubble

Home

0.000***

0.002**

In Bubble

Away

0.223

.042*

* p < 0.05, ** p < .01, *** p <.001

Chang and Ran

21

References

Belhumer, Kevin. “How Important Is Home-Court Advantage in the NBA.” Bleacher Report

(February 2013)

Carré, Justin, C Muir, J Belanger, and S Putnam. “Pre-Competition Hormonal and Psychological

Levels of Elite Hockey Players: Relationship to the ‘Home Advantage.’” Physiology &

Behavior 89, no. 3 (October 30, 2006): 392–98.

Carré, Justin. “No Place like Home: Testosterone Responses to Victory Depend on Game

Location.” American Journal of Human Biology 21, no. 3 (May 2009): 392–94.

Carron, Albert V, Todd M Loughhead, and Steven R Bray. “The Home Advantage in Sport

Competitions: Courneya and Carron’s (1992) Conceptual Framework a Decade Later.”

Journal of Sports Sciences 23, no. 4 (April 2005): 395–407.

Dohmen, Thomas J. “The Influence of Social Forces: Evidence From The Behavior of Football

Referees.” Economic Inquiry 46, no. 3 (September 2008): 411-424.

Downward, Paul, Marc Jones “Effects of crowd size on referee decisions: Analysis of the FA

Cup.” Journal of Sports Sciences 25, no. 14 (December 2007): 1541-1545.

Entine, Oliver A, and Dylan S Small. “The Role of Rest in the NBA Home-Court Advantage.”

Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports 4, no. 2 (January 28, 2008).

Goldman, Matt, and Justin M Rao. “Effort vs Concentration: The Asymmetric Impact of

Pressure on NBA Performance.” MIT Sloan Sports Analytics (March 2012).

Goumas, Chris. “Home advantage in Australian soccer.” Journal of Science and Medicine in

Sport 17, no. 1 (February 2013): 119-123.

Greer, Donald L. “Spectator Booing and the Home Advantage: A Study of Social Influence in

the Basketball Arena.” Social Psychology Quarterly 46, no. 3 (September 1983): 252.

Lopez, Michael J, Gregory J Matthews, and Benjamin S Baumer. “How Often Does the Best

Team Win.? A Unified Approach To Understanding Randomness in North American

Sport” Annals of Applied Statistics (January 21, 2017).

McHill, Andrew W., and Evan D. Chinoy. “Utilizing the National Basketball Association’s

COVID-19 Restart ‘Bubble’ to Uncover the Impact of Travel and Circadian Disruption

on Athletic Performance.” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (December 2020)

Neave, Nick, and Sandy Wolfson. “Testosterone, Territoriality, and the ‘Home Advantage.’”

Physiology & Behavior 78, no. 2 (February 2003): 269–75.

Chang and Ran

22

Nevill, Alan M, Nigel J Balmer, and A Mark Williams. “The Influence of Crowd Noise and

Experience Upon Refereeing Decisions in Football” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 3,

no. 4 (October 2002): 261-72

Nevill, Alan M., and Roger L. Holder. “Home Advantage in Sport: An Overview of Studies on

the Advantage of Playing at Home.” Sports Medicine 28, no. 4 (1999): 221–36.

Newcomb, Tim. “Facts about floors: Detailing the process behind NBA hardwood courts.”

Sports Illustrated. (December 2015)

Pollard, Richard. “Home Advantage in Football: A Current Review of an Unsolved Puzzle.” The

Open Sports Journal, no. 1 (June 2008): 12-14.

Roeder, Oliver. “Do NBA Refs Favor the Home Team.” The Pudding. (2017)

Schwartz, Barry, and Stephen F Barsky. “The Home Advantage,” Oxford University Press 55,

no. 3 (March 1977): 641-61.