Louisiana State University Louisiana State University

LSU Scholarly Repository LSU Scholarly Repository

Honors Theses Ogden Honors College

4-2020

The relationships between extracurricular activities, rehearsal, and The relationships between extracurricular activities, rehearsal, and

short-term memory recall in children short-term memory recall in children

Scarlett Hammond

Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.lsu.edu/honors_etd

Part of the Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Hammond, Scarlett, "The relationships between extracurricular activities, rehearsal, and short-term

memory recall in children" (2020).

Honors Theses

. 628.

https://repository.lsu.edu/honors_etd/628

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ogden Honors College at LSU Scholarly Repository. It

has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Scholarly Repository. For

more information, please contact [email protected].

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 1

The relationships between extracurricular activities, rehearsal, and

short-term memory recall in children

by

Scarlett Hammond

Undergraduate honors thesis under the direction of

Dr. Emily Elliott

Department of Psychology

Submitted to the LSU Roger Hadfield Ogden Honors College in partial fulfillment of

the Upper Division Honors Program.

April 2020

Louisiana State University

& Agricultural and Mechanical College

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 2

Abstract

Flavell, Beach and Chinsky (1966) completed a pioneer study on the evolution of spontaneous

verbal rehearsal in memory tasks as children go through formal schooling. They determined that,

as children progress through developmental stages, they begin to verbalize more during memory

tasks to remember information presented to them. This verbalization is one “rehearsal strategy”

that children develop. Miller, McCulloch, and Jarrold (2015) found that it is possible to teach

children rehearsal strategies through “rehearsal training” which in turn improved overall recall in

comparison to interactive imagery training. Rehearsal training can be seen in a variety of

activities, especially extracurricular activities such as sports or dancing that may involve the

utilization of rehearsal strategies. This study looked at the possible correlations between

extracurricular activities, rehearsal, and short-term recall in elementary school children ages 5 to

11. Participants completed a recall task that evaluated rehearsal strategies and their guardian

filled out a survey regarding the participant’s extracurricular activities. Results showed a

significant positive correlation between extracurricular hours and serial position scores. There

was a nonsignificant negative correlation between extracurricular hours and verbalization and

between verbalization and serial position scores. These findings indicate that increased

extracurricular activity hours may contribute to better performance on short-term memory recall

performance. Additionally, the findings indicate that verbalization does not have an effect on

serial position scores and is not affected by extracurricular hours.

Keywords: extracurricular, rehearsal, recall, short-term memory

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 3

In the age of technology, children are going outside less and less during the day, meaning

that their levels of physical activity have decreased substantially. It is important to consider the

effects that increasing a child’s physical activity can have on their cognitive abilities. Previous

studies have shown that as children progress developmentally, they tend to remember

information better through the acquisition of memorization techniques such as verbalization

(Flavell, Beach, & Chinsky, 1966). There have also been studies that show increased physical

activity can help improve these cognitive processes and academic performance (Kamijo,

Pontifex, O’Leary, Scudder, Wu, Castelli, & Hillman, 2011). However, few studies thus far have

examined the effect that increased physical activity, specifically in extracurricular activities that

utilize routine, can have on memorization.

Rehearsal in Children

Working memory refers to “the ability to store and manipulate information over brief

periods of time” (Miller et al., 2015, p. 1). Common tasks for measuring working memory

involves the serial ordering of some information and a distraction task to see how well a

participant can remember information after faced with a disruption, something this study will be

utilizing. A person’s performance on working memory tasks has been associated with predictions

to academic performance, intelligence, and classroom behavior (Miller et al., 2015). Although

working memory differs from short-term memory, the two have a close relationship; short-term

memory is considered to focus on just storage of information, while working memory is a

process for storing and manipulating information into your memory. For my study I am using the

term short-term memory recall (STM) because the delay period, which will be explained further

on in the methods section of this paper, does not contain a distraction task.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 4

In their experiment, Miller et al. (2015) looked at different rehearsal strategies that

children used to remember information, and trained participants in those strategies to determine

how recall was affected. A rehearsal strategy is something used to remember information as it is

being presented. The three types of training used in the experiment were cumulative rehearsal,

interactive imagery, and passive labeling. Also known as cumulative sub-vocal rehearsal,

cumulative rehearsal is when someone repeats a sequence in their head over and over in the

correct serial order. For interactive imagery, the children were instructed to visualize each of the

objects they were shown and to imagine those objects “being joined together and interacting with

one another” (Miller et al., 2015, p. 2). The final rehearsal strategy was passive labeling, where

participants were instructed to only name the item they just saw to themselves, differing from

cumulative rehearsal where they named all the objects in serial order repetitively.

The results from Miller et al. (2015) showed that participants in the rehearsal groups

performed better in terms of recall than those in the control group (passive labeling) no matter

what age. Additionally, the three groups of participants, which were also classified into two

different age groups, were matched by their initial level of performance on the verbal short-term

memory task. This finding is interesting considering there is a widely-held believe that younger

individuals are “either unable to rehearse, or show impoverished verbal serial recall because they

do not spontaneously engage in rehearsal” (Miller et al., 2015, p. 1). This idea, that as children

advance in age they being to rehearse more, is something Flavell et al. (1966) looked at in their

seminal experiment.

Flavell et al. (1966) discovered in their study of children ages 5 to 11 that, as they progressed

in age, children tended to display more verbalization (i.e. rehearsal) in memory tasks. This study

looked at how children verbalize and examined two different hypotheses that may explain a

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 5

deficiency that younger children experience in “verbal mediated performance”. The two

hypotheses, known as mediational-deficiency and production-deficiency, were originally

classified as one until it was realized that there needed to be further specification on the topic.

The new “mediational-deficiency” hypothesis that Flavell et al. (1966) used states that children

are able to produce verbalizations when they should, but these verbalizations do not mediate like

they should, making them useless. The “production-deficiency” hypothesis, on the other hand,

states that a child may know the appropriate words for the situation, but they fail to produce the

words verbally.

The purpose of the Flavell et al. (1966) was to examine this second hypothesis, the

production-deficiency hypothesis. To do so, they gathered a group of children ages 5 – 11 as

participants and administered a task to test their memory recall and verbalization abilities. This

task was replicated in this current study, and involved children being presented with a set of

pictures and then being asked to either immediately recall the pictures and the order they were

shown or experience a delay of approximately fifteen seconds before being asked to recall the

pictures and the order they were shown. Participants in this study were watched by an

experimenter who judged the amount of verbalization a child produced and classified it as no

verbalization or verbalization that did not constitute labeling, verbalization that was not

completely intelligible but could be understood as labeling, and verbalization that was clearly

labeling. Verbalization included both lip-movement and sounds made.

Their study confirmed one of the two hypotheses, the “production-deficiency hypothesis”,

which stated that children can use strategies they are taught by others to remember information

but cannot produce strategies on their own. The results from this study showed that the younger

children were less likely to show rehearsal or verbalization in the recall task in comparison to

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 6

older children which falls in line with the hypotheses they made concerning the experiment. The

current study aimed to replicate these findings concerning verbalization and rehearsal in

children.

The Effects of Extracurricular Activities

López-Vicente, Garcia-Aymerich, Torrent-Pallicer, Forns, Ibarluzea, Lertxundi,

González, Valera-Gran, Torrent, Dadvand, Vrijheid, and Sunyer (2017) looked at the long-term

effects of physical activity and sedentary levels on working memory performance in early

childhood through a longitudinal study focusing on several age groups. There were two age

groups in this study, a younger subcohort which consisted of participants who started the study at

4 years of age and an older subcohort whose participants started the study at 6 years of age.

Mothers of the children in each subcohort filled out a survey regarding their child’s physical

activity and sedentary levels once they were recruited (when their child was either 4 or 6,

depending on the subcohort in which they were placed). Although the survey questions were not

identical across the regions, they were all formatted to receive a similar answer, which was the

amount of time their child spent on a specific activity. Once answered, the researchers

transformed the categorical variables to continuous variables to ensure that the answers were

uniform in format.

The working memory portion of this experiment took place several years after these

surveys were completed. Children in the younger subcohort completed the task once they

reached 7 years of age and children in the older subcohort completed the task once they reached

14 years of age. The session took 25 minutes and involved child participants completing an n-

back test. In this n-back test “participants have a sequence of stimuli on the computer screen, one

at a time, and they have to respond (hit a button) when the current stimulus matches the one

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 7

presented n steps before” (López-Vicente et al., 2017, p. 36). Participants completed 25 trials and

three levels of difficulty (1-, 2-, and 3-back) for a total of 75 trials.

For their results, the researchers focused on accuracy in the 2-back trials because “it

showed better properties than the 1- and 3-back tasks (e.g., clear age-dependent slope and little

learning effect) in a previous study” (López-Vicente et al., 2017, p. 36). After analyzing their

results, researchers found that there was no significant difference in memory performance in the

younger subcohort between those with lower or higher levels of physical activity. However, they

do say throughout the rest of the article and in their summary that low levels in the younger

subcohort were associated with working memory performance at a later age. In the older

subcohort, they found that lower levels of activity led to a 4.22% decrease in correct responses

on the n-back test. Additionally, high levels of sedentary behaviors were associated with a 5.07%

decrease in correct responses in males in the older subcohort. Although this longitudinal study

helps us better understand the impact physical activity levels can have later on in life, it does not

provide a clear enough pathway from physical activity to increased memory performance. The

physical activity measurements were taken at the beginning of the study and no follow-up

questions were asked to determine if a participant’s physical activity levels had significantly

changed. To find a clearer path between the two variables, I examined Kamijo, Pontifex,

O’Leary, Scudder, Wu, Castelli, and Hillman (2011), who tested the effects of physical activity

intervention on working memory.

In Kamijo et al. (2011), researchers recruited forty-three children and divided them into

two groups: a waitlist control group and a physical activity program group. Children in the

physical activity intervention group spent two hours each day after school participating in

activities that focused on cardiorespiratory fitness or muscle fitness, depending on the day.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 8

Additionally, the children played organizational games that centered around a skill, such as

dribbling. To measure cognitive ability, each participant completed the modified Sternberg task

made by researchers. In this Sternberg task, participants were presented with a set of uppercase

consonants that were either 1, 3, or 5 letters in length. They were then immediately presented

with a lowercase consonant that was flanked on each side with question marks (to correspond

with the number of letters in the initial presentation). Participants then pressed one of two

buttons to indicate if the uppercase version of that letter had been present in the initial

presentation they had just seen of uppercase consonant letters. For example, participants may be

presented with the letters “LSRMK” and then “??r??”, at which point they should press the

button that indicates the “r” was presented before. Participants completed four blocks of 45 trials

of this task.

After analyzing the data for task performance, researchers reported that participants in the

intervention group saw overall significant improvement in their scores on the Sternberg post-test

(p = .002; 58.4% accuracy to 68.5% accuracy), in comparison to the waitlist control group which

saw no improvement in scores (p = .9; 65.6% accuracy to 66.0% accuracy). As expected, there

were significant decreases in response accuracy as participants were presented with trials

containing more letters. Additionally, differences in response accuracy between groups became

smaller as participants completed trials containing 3 (70.4% accuracy for intervention and 68.2%

for control) and 5 letters (61.0% for intervention and 61.1% for waitlist). Interestingly, while

response accuracy increased for the intervention group (66.0% to 74.1%) they decreased for the

waitlist group (72.9% to 68.8%).

It is important to note that in Kamijo et al. (2011) the intervention group did not have

significantly higher response accuracy in the post-test compared to the waitlist group, they just

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 9

had a significant improvement from their pre-test response accuracy scores. Although the

researchers say that “preliminary t-tests were conducted to confirm that there were no significant

differences in response accuracy between groups at pre-test for each letter condition”, the

significant results in post-test for the intervention group would suggest otherwise (Kamijo et al.,

2011, p. 8). Because the post-test results were not significant between the two groups, a

significant difference in their pre-test would provide an explanation for the researchers’ results.

Overall, Kamijo et al. (2011) did show that physical activity intervention can have a direct result

on a child’s ability to perform on a working memory task.

Furthermore, Hsieh, Fung, Tsai, Chang, Huang, and Hung (2018) looked at the

relationship between physical activity and working memory in their experiment in a small group

of children in Taiwan. Hsieh et al. (2018) classified their participants into two groups, high

physical activity (HP) and low physical activity (LP) based on measurements from an

accelerometer. Groups were determined based on the median number of accelerometer counts

per minute (median = 846 counts). Participants were then given a delayed matching test to

evaluate perceptual working memory. This test had two sections which were classified as

delayed and non-delayed. In the delayed condition participants were presented with a rectangle

with a dot inside of it, at one of nine possible positions, on either the right or left of a plus sign in

the middle of the screen. Next a screen with just the plus sign in the middle was shown for 3

seconds before another rectangle appeared. Participants had to determine if the dot was in the

same place as the previous rectangle or if it had moved. In the non-delayed condition, both

rectangles were presented at once and participants had to determine if the dots in each of the

rectangles were in the same position. Their results found that children in the HP group had

higher accuracy rates (F(1,30) = 4.96, p <.05, η

p

2

= 0.61) compared to children in the LP group.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 10

Current Study

This current study examined how extracurricular activities affected the rehearsal strategies a

child uses to remember information presented in a short-term memory recall task. Additionally,

it examined the effect that long-term extracurricular activities can have on short-term memory

performance. It is an extension of the Elliott et al. (2019) study, which is a multi-lab direct

replication of Flavell, Beach, and Chinsky (1966). This study followed the methods section of

the Elliott et al. (2019) study with the addition of a questionnaire completed by parents

concerning their children’s extracurricular activities. Based off of previous studies, I

hypothesized that than an increase in extracurricular activities may lead to better performance on

the short-term memory task. Additionally, I hypothesized that greater extracurricular activities

may cause a child to perform better than another child who is similar in age or slightly older.

Participants

Participants were recruited from various elementary schools located in Baton Rouge,

Louisiana. An email was sent to school principals explaining the project and asking them to

share the signup form with the guardians of children in kindergarten through fifth grade.

Additionally, Dr. Elliott reached out to several colleagues at Louisiana State University who had

children that fell within our desired age range. A total of 57 children agreed to participate in the

study, (24 male, 33 female). Following the in-person session, the survey sent out to guardians

regarding extracurricular activity performance received 29 completed responses. Of those 29

completed responses, 3 were excluded because the children did not participate in the study but a

sibling did, 1 was excluded because the parent filled out the survey twice, and 2 were excluded

because they began the testing portion of the study but were unable to finish or their data were

unusable due to not following directions. Additionally, one parent filled out one survey for her

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 11

twin daughters, but follow-up contact established that both children completed the same

extracurriculars and therefore could be counted twice. In the end, 24 children (13 females, 11

males) who participated in the study and whose parent also completely filled out the survey

regarding extracurriculars were included in the analyses.

Procedure

Testing for this study took place in two different environments. The majority of children

were tested in Dr. Emily Elliott’s lab located on Louisiana State University’s campus in

Audubon Hall. Some children were tested at their local elementary school, during their after

school program, in the school’s library or an empty classroom. Both locations had relatively the

same set up and testing was conducted in the same order and manner in both locations.

Participants sat behind a computer screen with an experimenter on the side of them to facilitate

the computer program used to run the test and explain the study to the participant. For most

trials, there were between one and two coders also in the room sitting a few feet from the

experimenter and participant depending on availability for that day. However, when there was no

coder in the room the computer’s built-in camera was used to record the session. Later on, coders

went through the video and coded the child’s verbalization throughout the test. A minor assent

form was procured from the participant before the test began in addition to the consent form

filled out by the participant’s guardian.

The experimenter and participant sat in chairs behind the computer screen while the test

was conducted. First, the demographic information was entered for that participant which

included: participant number, research group (LSU), age in months, grade in school, and gender

(in that order). The experimenter then explained what the memory recall task would consist of

based on prompts from the computer program. The experimenter explained that several pictures

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 12

would appear in a line on the screen and the participant was expected to memorize, to the best of

their ability, the pictures that were highlighted by an orange color and the order in which they

were highlighted. Participants then went through two practice trials, the first with two pictures

being highlighted and the second with four pictures being highlighted and were asked

immediately to recall the pictures they saw following each trial, by pointing to the pictures in

order. It was emphasized to participants that they should just point to the pictures during the

recall phase, and no mention was made of having them name the pictures for the first two

sections of the memory recall task. Participants were then asked if they had any questions

concerning the practice trials they just did, and if they did not then the experimenter proceeded to

explain the next step.

It was then explained that during some trials they would be asked to wear a pair of

painter’s-taped sunglasses during a “delay” period of fifteen seconds. Participants were given the

opportunity to practice putting the sunglasses on for fifteen seconds to get a feel for how long

they would have to remain on, some chose to practice putting the sunglasses on while others did

not. With the practice trials over and the role of the sunglasses in the delay period explained, the

test began. Each participant experienced all three sections of the memory recall: delayed recall,

immediate recall, and point-and-name recall. The delayed recall involved the presentation of

pictures, wearing the sunglass for fifteen seconds, and then the recall of the pictures in the order

they were seen. The immediate recall followed the same procedure minus wearing the sunglasses

for fifteen seconds. The point-and-name recall mirrored the delayed recall, but during the

presentation and recall phases the participants were asked to point and name the objects that they

saw highlighted and the order they saw them; respectively.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 13

Each section of the memory recall task involved eight trials, two trials for each number

sequence of pictures (two, three, four, and five) and the trials progressed sequentially, meaning

that during the delay trials participants saw two of the two-picture trials first, then the two three-

picture trials, and so on until they finished with the two five-picture trials before heading onto

the next section. Participants experienced either the delay or immediate recall section first, based

on randomization from the computer program, followed by whichever was left from that pair,

and the point-and-name section always last. After the delayed recall section participants were

asked how they remembered the sequence of pictures (see Appendix B for a copy of the

questionnaire). Before each point-and-name section participants were asked to name the seven

pictures one at a time to ensure that the participants had a verbal label for each item (see

Appendix C for a copy of the pictures). Once the point-and-name section was finished

participants were informed that they had finished the test, were allowed to pick out a prize, and

returned to their guardian who was waiting just outside the testing room.

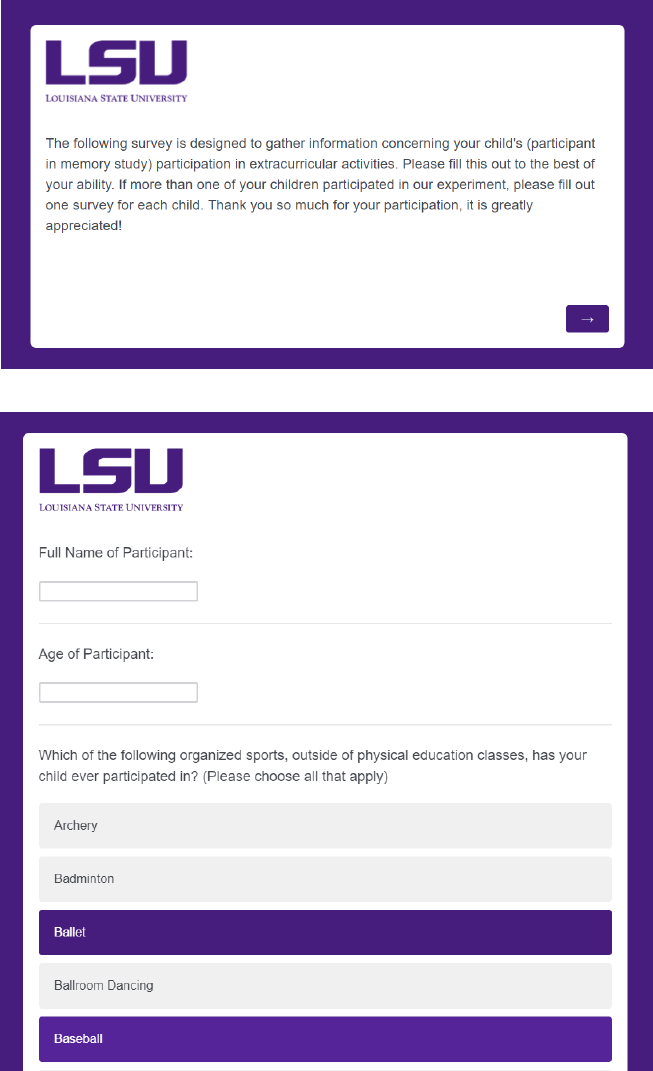

A survey regarding extracurricular activities was emailed out to the parents after

participant testing was finished (see Appendix A for a copy of the questionnaire). It was

determined that the guardians would be able to give the most accurate answers for the

questionnaire in comparison to the participants. This survey was constructed through LSU

Qualtrics and was distributed to guardians in December of 2019. In the survey, guardians were

asked to choose from a list what extracurriculars their child participated in, with an option at the

end for them to write in any activities that may have been left of out the list. After choosing the

activities they then answered questions concerning the amount of time their child had been

involved in each activity such as hours per week and months per year. The second section of the

questionnaire resembled the first but focused on musical instruments that their child practiced.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 14

Results

To analyze the data from this study I utilized a correlation analysis to test the

relationships of our variables (extracurriculars, rehearsal, and working memory; see Table 1).

The goal of this analysis was to determine how extracurriculars affect the amount of rehearsal a

participant engages in, whether increased rehearsal affects accuracy in a short-term memory task,

and if high levels of extracurriculars activities correlated to higher accuracy in the memory task.

Results showed a non-significant negative correlation between verbalization and extracurricular

hours (p = 0.613, Pearson’s r = -0.109). There was also a non-significant negative correlation

between verbalization and serial position score (p = 0.325, Pearson’s r = -0.210). The analysis

showed a significant positive correlation between extracurricular hours and serial position score

(p = 0.013, Pearson’s r = 0.499). Other significant results are between age in months and

extracurricular hours (p = 0.003, Pearson’s r = 0.586) and between age in months and serial

position score (p < 0.001, Pearson’s r = 0.499). There was a non-significant negative correlation

between age in months and mean verbalization score (p = 0.640, Pearson’s r = -0.101). A

mediation analysis was conducted with extracurricular activities acting as the mediator on ages

in months for serial position score (see Table 2). There was a nonsignificant indirect mediation

effect (p = 0.873) and a significant direct mediation effect (p < .001).

Discussion

The first hypothesis for this study was that higher levels of extracurricular activity may

lead to better performance on the short-term memory task. This hypothesis was supported based

on the results of the memory recall task. The correlation analysis showed that as participants

spent more hours in extracurriculars activities their chances of a higher serial position recall

score rose. Although in the proposal for this study I expressed the idea that this correlation would

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 15

be the result of children better rehearsal from their extracurricular activities, the correlation

analysis between extracurricular hours and mean verbalization was non-significant. However, the

insignificant negative trend towards 1 (which indicated clear verbalization during testing trials)

indicated that further testing with larger sample sizes would be a promising future direction.

Additionally, this study derived verbalization as a measure of rehearsal in participants

from Flavell et al. (1966) but did not find the same results as their study (see Table 3). While

Flavell et al. (1966) found that children verbalized more as they aged, this study found no

significant correlation between age and verbalization scores. In fact, the results showed a slight,

non-significant negative correlation between the two variables. Due to the age of the original

study, it is possible that children have learned other, internal rehearsal strategies that are more

effective and have caused the decrease in verbalization scores. Miller et al. (2015) explored two

different types of non-verbal rehearsal, which are cumulative sub-vocal rehearsal and interactive

imagery, in their study. It is possible that children are practicing these internal rehearsal

strategies and are becoming more successful at internalizing rehearsal as they age.

There are other factors that may explain the correlation between extracurricular activity

and serial position recall scores besides rehearsal. Physical activity has been known to have

effects on cognitive performance because of increased blood flow to the brain. One way to test

this difference would be to have an experiment with two different groups of physical activity:

extracurricular activities that involve strategy and regular physical activity, such as running, that

do not involve strategy. Additionally, a demographics survey for parents and guardians to fill out

could be used to account for other variables that may influence outcomes such as socioeconomic

status, access/use of tutoring services, and reading levels outside of schoolwork.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 16

The second hypothesis that greater levels of extracurricular activity may cause a child to

perform better than another child who is similar in age or slightly older is not supported by the

results. The idea behind this hypothesis was that extracurricular activities would again improve

rehearsal in children and therefore help them perform better on a short-term memory recall task.

However, the results of the mediation analysis of extracurricular activities on the relationship

between age and serial position score show otherwise. It is possible that more extracurricular

activities may put a child above other people in their age group but not above or at the same level

as children ahead of them because of other factors involved in a child’s abilities to rehearse and

recall information. The educational tools children are given as they advance through school

could be what set the older children apart in terms of serial position scores, despite having

similar or fewer hours of extracurricular activities. Additionally, higher attention spans and

continuing brain development could play a role.

There are several improvements that could be made for future replications or extensions

of this study. The largest obstacle faced in this study involved the survey portion which would

need to be modified for future usage. There were errors in the collected questionnaire data

because guardians were allowed to write-in their answers for each question after selecting their

child’s extracurricular activities. One possible solution for this would be changing the answer

format to a drop-down list for each question. For example, for a question like, “what months out

of the school year did your child participate in an activity?”, there would be a drop-down menu

for the start month and end month.

Another future improvement to this study would be having guardians fill out the survey

while their child is participating in the memory recall task, which would also give them

something to do while their child was being tested. There were some instances where parents

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 17

wanted to be in the room with their children which resulted in possible distractions for the child.

Additionally, having guardians fill out the survey when they bring their child in for testing would

ensure that we would collect a timely and accurate response. There were 57 participants that

were run through the memory recall task and less than half of those had a survey filled out by

their guardian. The survey for this study was sent out anywhere from a few weeks to several

months after the child participated in the recall task, which was detrimental to the response

count. There is a possibility that guardians unknowingly put in extracurricular hours from after

their child participated in the memory recall task but before they received the questionnaire.

Having the survey done immediately upon arrival would likely mean receiving a more accurate

response and being able to sort out any problems guardians may face with the survey in a timely

manner.

Another improvement would be to do further analysis on the different sections of the

memory recall test. Some participants performed very well on certain sections and then

performed poorly on others (See Table 4). Further research could be done into the cause of this

difference and whether it has to do with the difference between sections (such as initial rehearsal

in the point-and-name section compared to the first two sections). By breaking down the

different sections of the memory task, further exploration could also be done on the effects of

different extracurricular activities on these sections. Different extracurricular activities promote

different types of rehearsal and memory recall, which the testing portion of this study does

through its three sections. However, research into this idea required also looking at the

limitations of this study.

The limitations of this study revolved largely around the sample size of this study. Earlier

in this discussion it was mentioned that a future experiment could look at two different types of

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 18

physical activity which were extracurricular activity and “regular” physical activity. A larger

sample size would allow for this to happen, in addition to further distinguishing between types of

extracurricular activities. Different extracurricular activities require different levels of rehearsal

and strategizing and classifying these as higher or lower in terms of rehearsal would be

beneficial for future research. Additionally, a larger sample size would allow for partial

correlations to control for age in months. The sample size of the current study was too small to

successfully complete additional analyses.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicated that children who participate more in

extracurricular activities may have better short-term memory. The results also indicated that an

increase in extracurricular hours does not lead to an increase in verbalization. Finally, the results

of this study indicated that verbalization does not have an impact on short term memory recall

and provided several clear avenues for future research.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 19

References

Elliott, E. M., Morey, C. C., & AuBuchon, A. (provisionally accepted). Registered replication

report of Flavell, Beach, and Chinsky (1966). Advances in Methods and Practices in

Psychological Science.

Flavell, J. H., Beach, D. R., & Chinsky, J. M. (1966). Spontaneous verbal rehearsal in a memory

task as a function of age. Child Development,37(2), 283-299. doi:10.2307/1126804

Hsieh, S., Fung, D., Tsai, H., Chang, Y., Huang, C., & Hung, T. (2018). Differences in working

memory as a function of physical activity in children. Neuropsychology,32(7), 797-808.

doi:10.1037/neu0000473

Kamijo, K., Pontifex, M. B., O’Leary, K. C., Scudder, M. R., Wu, C., Castelli, D. M., & Hillman, C.

H. (2011). The effects of an afterschool physical activity program on working memory in

preadolescent children. Developmental Science,14(5), 1046-1058. doi:10.1111/j.1467-

7687.2011.01054.x

López-Vicente, M., Garcia-Aymerich, J., Torrent-Pallicer, J., Forns, J., Ibarluzea, J., Lertxundi, N., .

. . Sunyer, J. (2017). Are Early Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors Related to Working

Memory at 7 and 14 Years of Age? The Journal of Pediatrics,188, 35-41.

doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.079

Miller, S., McCulloch, S., & Jarrold, C. (2015). The development of memory maintenance

strategies: Training cumulative rehearsal and interactive imagery in children aged between 5 and

9. Frontiers in Psychology,06. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00524

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 20

Table 1

Correlation Matrix of Extracurricular Hours, Age in Months, Mean Verbalization Scores,

and Serial Position Scores

Ex. Hours

Age in

Months

Mean

Verb.

SP

Score

Ex. Hours

Pearson's r

—

p-value

—

Age in Months

Pearson's r

0.586

**

—

p-value

0.003

—

Mean Verb.

Pearson's r

-0.109

-0.101

—

p-value

0.613

0.640

—

SP Score

Pearson's r

0.499

*

0.826

***

-0.210

—

p-value

0.013

< .001

0.325

—

Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Table 2

Mediation Estimates of Extracurricular Hours

Effect

Estimate

SE

Z

p

Indirect

0.0125

0.0778

0.160

0.873

Direct

0.7609

0.1328

5.729

< .001

Total

0.7734

0.1077

7.179

< .001

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 21

Figure 1:

Histogram and Scatterplot Graphs Among the Four Variables.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 22

Table 3

Number of Ss Showing 1+ Verbalization Instances on Each Segment of Each Subtask.

Segments and Subtasks

Presentation

Delay

Recall

Age

IR

DR

DR

PN

IR

DR

5 (5)

2

2

3

4

3

3

6 (2)

0

0

0

1

2

0

7 (2)

1

2

1

2

2

2

8 (8)

5

5

6

5

7

6

9 (1)

1

1

1

1

1

1

10 (3)

1

3

1

2

2

3

11 (3)

3

3

3

3

3

3

Note. In parentheses beside each age number is the number of participants in that age group.

Table 4

Number of words recalled in the correct serial position by each participant.

Memory Recall Test Section

Participant ID

Delayed

Immediate

Point & Name

Grand Total

107

4

2

9

15

108

5

9

4

18

109

9

14

20

43

111

4

4

7

15

114

3

13

8

24

118

12

8

3

23

200

14

22

12

28

201

27

27

21

75

202

22

25

23

70

203

10

17

12

39

210

7

10

10

27

215

13

20

11

44

302

13

21

16

50

303

12

17

12

41

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 23

304

16

20

15

51

311

21

19

24

64

313

10

9

6

25

314

19

17

20

56

400

28

27

28

83

406

26

20

17

63

411

26

25

28

79

412

23

25

25

73

500

26

19

18

63

510

15

24

16

55

Grand Total

375

431

383

1169

Note. The maximum possible recall score for each participant was 84.

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 24

Appendix A

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 25

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 26

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 27

Appendix B

EXTRACURRICULARS, REHEARSAL, AND STM 28

Appendix C

comb flag pencil

apple moon owl flower